Jack Mintz's Claims about Capital Gains Impacts Are Not Backed up By Reason, Logic or Evidence

Canada’s political discourse is being polluted by reports that are nothing more than a deceptive sales pitch based on economists making stuff up

Jack Mintz, professor of finance, has written a post making blatantly deceptive claims about the Government of Canada’s decision to raise the capital gains tax. It’s been published on The Hub Canada, and reprinted on the website of the MacDonald Laurier Institute.

The claims it makes about the economic impact of recent changes to Canada’s capital gains taxes are ridiculous, because the argument is makes are untenable. They are build on sand. They ignore reality, and perhaps most important of all, they ignore all of the ways in which this preferential tax treatment of earning from owning compared to earning from working can be exploited in ways that distort the market and the economy for the worse.

I’ll provide a detailed critique, but first I want to make the point about why it’s perfectly acceptable for a non-economist such as myself to critique Mintz’s work, or that of other economists.

One of the reasons that political discourse is breaking down is that the only that matters is whether something is persuasive and believable, not whether it is true or even possible.

First, neoclassical economics makes many foundational assumptions that are not supported by evidence of any kind. You do not have to be a scientist or an economist to realize that if you make up one of the inputs going into a process, it’s garbage in, garbage out.

In his 2016 blistering critique of neoclassical economics, Paul Romer said economists were routinely relying on what he called “facts with an unknown truth value”.

“Macro models now use incredible identifying assumptions to reach bewildering conclusions. To appreciate how strange these conclusions can be, consider this observation, from a paper published in 2010, by a leading macroeconomist:

... although in the interest of disclosure, I must admit that I am myself less than totally convinced of the importance of money outside the case of large inflations.’”

In Section 2, Romer writes of “Post-real models.”

You don’t have to understand anything of the above paragraph except the idea that anything at all is “caused by imaginary shocks.”

In response to the observation that the shocks are imaginary, a standard defense invokes Milton Friedman’s (1953) methodological assertion from unnamed authority that "the more significant the theory, the more unrealistic the assumptions (p.14)." More recently, "all models are false" seems to have become the universal hand-wave for dismissing any fact that does not conform to the model that is the current favorite.

The noncommittal relationship with the truth revealed by these methodological evasions and the "less than totally convinced ..." dismissal of fact goes so far beyond post-modern irony that it deserves its own label. I suggest "post-real."

This means that economists are just making shit up.

The problems with our current orthodox neoclassical economics are not because of difficult technical issues. They are because of basic mistakes in logic, reasoning, or by making assumptions that can’t be supported, according to basic principles of critical thinking and what it actually takes for something to qualify as evidence, or be supported as a fact that have been established by centuries of thought and analysis.

These aren’t woke or elite ideas, they’re the basic ways to test for BS. Just because those two things are associated in your head, doesn’t mean they’re associated in the real world.

The great physicist Richard Feynmann said “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.”

There are lots of fallacies we make - common mistakes in thinking - that people have catalogued and warned against over the centuries. They made the enlightenment, democracy, rights, the scientific revolution and all the technological and social progress we have seen possible, including human rights and liberation movements. All the stuff that is under full-blown assault right now by so-called traditionalists whose traditions include a disdain for the rule of law.

There have been a lot of critiques of “experts” lately, especially scientists and doctors, which are unscientific and grounded in rumour and superstition, which has been fanned by politicians and forces who want to see chaos and division.

Economics is not a profession like nursing, medicine, the law, engineering. In those professions there are standards in place standards of quality, based a wide range of tests to prove that information is credible, because people’s lives are in their hands.

Now, economic theories without question lead to death, misery and suffering, or prosperity and freedom. But they are not held to anywhere near the same standards of scrutiny or standards of any other discipline.

No matter who you support politically right now, and no matter what reason you think things are messed up, I’m telling you right now, if you are frustrated or angry, I guarantee it is because of an economic theory that’s denying reality.

This is why Paul Romer wrote “I have observed more than three decades of intellectual regress.” You do not have to have mastery of calculus to recognize that the basic standards of evidence and argument are not being met.

Earlier this year, Christine Lagarde, who is currently the head of the European Central Bank warned that economists’ track record of forecasting is “abysmal” and called them a “tribal clique.” When she was head of the IMF, an internal report showed the “Troika” in Europe - the EU, IMF and ECB - were responsible for the “immolation” of the Greek economy through forced austerity due to blunders in basic currency theory. The IMF’s “top staff misled their own board, made a series of calamitous misjudgments in Greece, became euphoric cheerleaders for the Euro project, ignored warning signs of impending crisis, and collectively failed to grasp an elemental concept of currency theory.”

For heaven’s sake - the Nobel Prize for Economics isn’t actually one of the Nobel prizes. It was created in the 60s so the Swedish Central Bank could provide unearned credibility to various neoliberal to libertarian economists whose work was - as Romer writes, based on imaginary ideas.

Where and why Mintz is wrong

I’ve already written explaining why the capital gains changes will help with the cost of living (and housing), because lots of people who don't want to pay taxes on capital gains are folks who have been profiting from driving up the price of real estate and rent.

First, Mintz has already written about the capital gains in support of an argument that it would affect a lot more people than claimed. This was also questionable.

In a previous DeepDive, I analysed the reach of the tax change by estimating the number of tax filers who would be affected over their lifetime. The key finding was that it would affect far more Canadians than the government seemed to anticipate. On a lifetime basis, I estimated that 1.26 million Canadians (almost 5 percent of taxpayers) will be affected by the increase in the capital gain tax on individuals, half of whom earn less than $117,000 per year. [Emphasis mine]

That last sentence has an undefined period of time (a lifetime) two different types of population (Canadians and taxpayers) and two types of taxes - capital gains, and income from earning.

Is the argument here just that, if you look at who pays this tax for 50 years, it’s a lot more people than pay in just one? Are people earning less than $117,000 a year in capital gains, or in income from work?

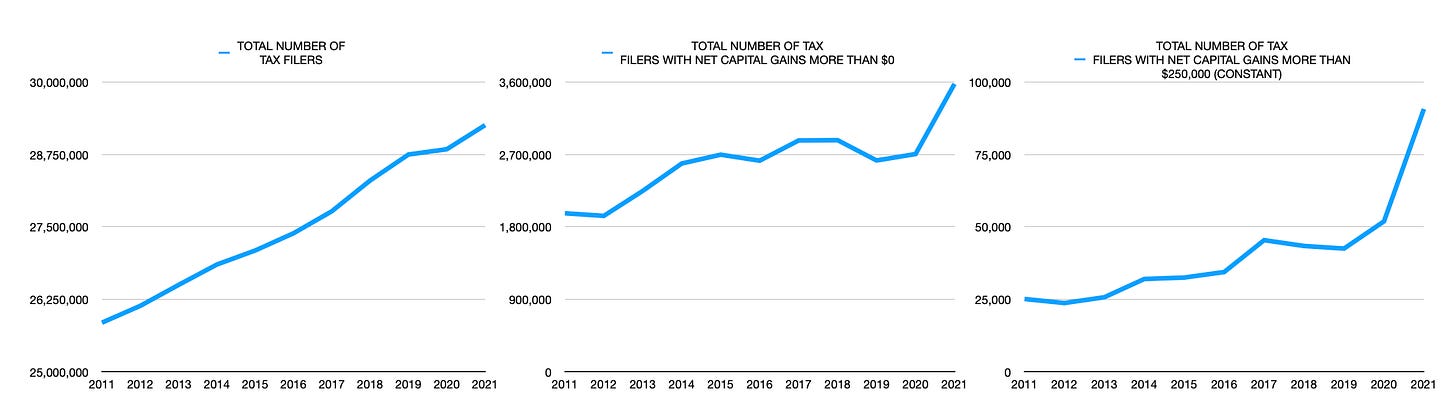

Mintz draws his data from this table - which tells an important story when you turn it into a chart.

What you see is that from 2011-2021 while the total number of tax filers has followed something close to a straight line, something happened to both capital gains filers and capital gains over $250,000 a year. The capital gains filers spiked up - and the gains over $250,000 a year spiked even higher and faster.

That spike is directly related to the spike in housing prices that started at the same time. These are the people who have been profiting from inflating the cost of housing, because they borrowing to speculate on real estate.

The capital they are investing is not going to create jobs or build factories. It is going into driving up the price of an existing asset, without increasing its productive value.

These are the people who have been profiting from the affordable housing crisis.

Its not money that’s been saved up. It’s borrowed. These are not long-term investments with a view to ongoing returns. They’re short term, and they investing in a property and selling it again.

In 2020, there were 51,900 people declaring over $250,000 in capital gains. The next year, 2021, there were 90,700, an increase of 75%. (!)

This was a capital tax gain structure that was incentivizing massive non-productive investments into driving up existing asset prices up - which is inflationary - instead of investing in creating new assets, which is not.

With stock options as compensation in the tech industry, this may also apply. The initial investment is fuelled by debt, not by savings.

The IMF and the Canadian Government say this won’t be a problem, but the Fraser Institute does.

Yet a key assumption of the government is that the tax increase will have a limited effect on Canada’s economy. In particular, the budget stated: “Increasing the capital gains inclusion rate is not expected to hurt Canada’s business competitiveness.

The International Monetary Fund reached a similar conclusion based on its focus on the capital taxes paid by individuals. It observed that “it [the tax change] is likely to have no significant impact on investment or productivity growth.”

These claims conflict with a large body of research on the economic costs of capital gains taxes.

This “large body of research” is a paper by the Fraser Institute. At some point in the future I will see if I can dissect it as well, but let’s be clear: the Fraser Institute is in the business of persuasion for a political purpose, not truth-telling.

Mr. Mintz, we would like to see the Napkin or Envelope you worked this out on.

The purpose of this latest DeepDive therefore is to better understand the economic effects of the capital gains tax increase—with a focus on investment, jobs, and GDP. In particular, I estimate Canada’s capital stock will fall by $127 billion; employment would decline by 414,000; GDP will fall by almost $90 billion; and real per capita GDP will decline by 3 percent.

This is ginned-up apocalyptic result. Quite seriously, these are extraordinary claims that demand extraordinary proof. Instead it is assumption after assumption.

4. The phony claim that if people have to pay taxes, they won’t invest

This phony argument is a decades old scare tactic to induce FOMO - fear of missing out. It’s been advanced on behalf of libertarians for decades, and it’s not true.

One of the reasons it’ not true is because it is rooted in the idea of “rational expectations” which is a fantasy that every person and investor makes decisions in the present based on what tax changes may be 20 years from now. Critically, it centres the argument on people who will go out of their way to avoid taxes, when the reality is that while many people would like lower taxes, there are people who never want to pay taxes at all.

This is a demand that we alter the entire tax system to conform to them. It’s important to recognize that there are two distinct groups who share a desire to avoid paying taxes on their investments - legitimate investors, and criminals. It has to be said - as has been noted by the International Centre for Investigative Journalists, who have been analyzing offshore tax havens, that companies that engage in tax avoidance also often “cut corners” to evade regulations in other ways.

What’s being invested in matters. The structure of capital gains taxes encourages certain types of activity. Debt-fuelled speculation in existing assets has negative impacts because it raises overhead - the cost of living and doing business - across the entire economy. Costly private overhead is a drag on the economy - for “real economy” businesses as well as consumers and households.

“Capital gains taxes hurt business investment

Neither the Department of Finance nor the IMF produced estimates of the impact of the capital gains tax increase on the economy, specifically investment, employment, and GDP. So why did they claim it had no impact on business competitiveness?

For the reasons I explained above: the capital isn’t being directed into the creation of new productive businesses. It is being used to speculate on flipping real estate and the difference in capital gains taxes is being exploited by speculators.

Without evidence, Mintz assumes others’ assumptions for them.

Here, Mintz is speculating as to why the IMF and the Government of Canada would disagree with him.

There are two possible reasons for this. First, it’s typical to assume Canada is a small open economy in capital markets. Under this assumption, businesses borrow freely in international markets at a world interest rate and Canadian saving has no discernible impact on the international interest rate. Even if capital gains taxes discourage Canadian investors from buying corporate equities and bonds, it will have no impact on business investment since companies still borrow at the same international market interest rate.

Second, the typical investment modeling by Finance Canada (the marginal effective tax rate) includes the corporate income tax and provisions, sales tax on capital inputs, and asset-related taxes. However, corporate capital gains taxes are not included in the modeling (only the personal capital gains tax is included). So, obviously, an increase in the corporate capital gains tax rate will have no impact on investment in the model.

He brings up two explanations based on what he says their “typical” assumptions would be. However, he doesn’t provide any citation or evidence.

He is assuming what others’ assumptions are, and then says those assumptions are wrong. This is the “straw man” fallacy:

Neither of these assumptions holds up. While the Canadian capital market is only 2.5 percent of the world stock markets, Canadian companies depend very much on equity capital provided by domestic households, even the largest companies. As many studies have shown, Canadians invest 52 percent of their equity portfolio in Canadian markets even though a properly diversified portfolio would suggest only a small portion of assets would be invested at home.

There are many reasons for “home bias” in equity shares. Smaller companies don’t have easy access to international markets. Companies that are Canadian-controlled need a significant share of Canadian ownership beyond 2.5 percent. Also, Canadians have more information about domestic opportunities and risks than they have with respect to international assets. While Canada doesn’t have capital controls (except Investment Canada limitations on foreign direct investment), the dividend tax credit and certain other tax preferences apply to only Canadian resident companies, not foreign ones. Thus, under home bias, capital gains taxes have been shown to suppress equity values and raise the cost of equity-financed investment of Canadian companies.

It’s not clear how Mintz’s estimates of the distribution of ownership of large companies is accurate, or relevant

Mintz links to a Statistics Canada page and says he estimates “that Canadian households own 35.5 percent of large company shares listed in Canada”.

It’s not clear how he reached that conclusion at all, since the page he links to does not mention large company shares at all. For decades, it has been recognized that concentrations of wealth and income follow a power law, as discovered by Vilfredo Pareto.

Based on Statistics Canada data, I estimate that Canadian households own 35.5 percent of large company shares listed in Canada. If there were no home bias, Canadian household ownership of Canadian companies would be obviously much smaller and have little impact on the cost of investment for large companies.

As Benoit Mandelbrot wrote:

“Pick a group of people to study — say, everybody making minimum more than the U.S. government’s $5.15 minimum wage, or $10,712 a year. Now ask: What percentage of people earn at least ten times that? According to Pareto’s formula, the answer should be 3.2 percent. Now go higher up the moneyed classes. What proportion earns more than $10.7 million? Answer: 0.1 percent And once more: What proportion earns more than $10.7 million, a thousand times the minimum? Answer: 0.003 percent — a very small number indeed.”

In 2006, a UN study showed that the world’s richest 1% owned 40% of all wealth, and that 50% of the world’s adults own just 1% of the wealth. In the U.S., the imbalance is actually greater: in the U.S. in 2007, the top 1% had 42.7% of the wealth; the next 19% had 50.2% of the wealth, and remaining 7% of the wealth was split between the remaining 80% of the population. A 2009 study of Canada showed 3.8% of Canadian households controlled $1.78 trillion dollars of financial wealth, or 67% of the total.

The point here is that even if Canadian households own 35.5% of shares in Canada’s large companies, the concentration of that ownership is not even or uniform.

As for corporate capital gains, they are paid when companies operate in Canada regardless of ownership. Corporate capital gains are earned when physical and financial assets are sold. Corporate capital gains taxes are also paid when corporate reorganizations take place such as in the case of mergers and acquisitions. Since the corporate tax applies to nominal capital gains, that capital gains tax increases the cost of investment even if there are no real capital gains.

It has to be said that Mergers and Acquisitions are also not necessarily “productive investment”. While they promise “efficiencies” they rarely deliver.

The idea that corporate mergers and government centralization will result in greater efficiencies because of administrative efficiencies often fail of their promise. They concentrate decision-making and power in the hands of a few, and that means a concentration of risk. There is another obvious reason ten medium sized companies may spread the wealth better than one giant company: You get ten sets of upper management making medium-sized executive salaries instead of one management team making a huge salary. You get ten companies with competing products hiring ten advertising agencies and buying more advertising.

When you have a monopoly - or an oligopoly, you don’t have to advertise at all.

More estimates and cherry picking data

Here, Mintz crams a string of estimates together, and it’s not clear that there is anything representative about the years he has picked.

From 2011 to 2021, taxable corporate capital gains are roughly 7 percent of corporate taxable income of non-financial corporations. Based on merger and acquisition data and the market value of the stock market, I estimate a fairly long holding period for corporate shares (35 years), not dissimilar for structures. Taking into account short holding periods for trading financial assets, I estimate that the annualized non-financial capital gains tax rate (the so-called accrual-equivalent capital gains tax rate) rose from 6.4 percent to 8.5 percent due to the budget’s capital gains tax hike.

What is the evidence and what are the assumptions that make the basis of all these estimates? In the last 25 years Canada has seen some of the most dramatic economic shocks imaginable, including wars, a global financial collapse, a collapse in the price of oil, and a pandemic, and now a housing and cost of living crisis.

Thus, the effect of the budget’s tax change is twofold. According to financial theory, the supply cost of equity increases as the personal tax on capital gains (and dividends) rises with income.

The financial theory that Mintz links to is an article by Merton Miller, who was awarded a fake Nobel prize in Economics for his work for the M & M theorem.

“The M&M Theorem, or the Modigliani-Miller Theorem, is one of the most important theorems in corporate finance. The theorem was developed by economists Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller in 1958. The main idea of the M&M theory is that the capital structure of a company does not affect its overall value.”

The first version of the M&M theory was full of limitations as it was developed under the assumption of perfectly efficient markets, in which the companies do not pay taxes, while there are no bankruptcy costs or asymmetric information. Subsequently, Miller and Modigliani developed the second version of their theory by including taxes, bankruptcy costs, and asymmetric information.” (Emphasis mine).

Miller thanks Myron Scholes and “especially Eugene Fama” who contributed to theories about efficient markets.

Myron Scholes was one of the architects behind the Black–Scholes–Merton formula, which drew from mathematical models to track rockets in flight and used it to calculate derivatives for what projecting what a future price would be. It also received the fake Nobel Prize, and they went to become advisors to a company, Long-Term Capital Management whose collapse in the 1998 was legendary. From Frontline:

And when they became more worried about risk -- and the firm had all sorts of models that said, no matter what happened, based on history, they couldn't lose more than $35 million a day -- they started dropping $300, 400, 500 million every day.

They had had $7 billion of capital. They thought they had so much capital, they gave back $3 billion to their investors right before this. Then they start losing these chunks.

Everyone else on Wall Street had similar bets to them. They're sort of sucked down into this vortex, and the more they try to sell out of these things, the more the steamroller goes.

And Wall Street freaks is what happens.

The New York Federal Reserve calls in the top 14, 15 banks to say: "LTCM's going to go down. Who knows who it'll take down with them? You guys ought to do something with them." And 14 banks agree to put up a few hundred million each, about $3.5 billion total. One bank refuses. That was Bear Stearns, incidentally.”

When the actual financial theorists Mintz is referring to applied their own theories, it created a market implosion.

“Long-Term had two Nobel Prize-winners, [economists] Bob Merton and Myron Scholes. Scholes, in particular, was a real free-market advocate. He used to say that only a fool paid his taxes. He didn't mean that people should be dishonest or illegal or commit crimes. He meant that anybody with a brain, half a brain, could figure out an honest way to get around them. And he was a specialist employed for that.”

What did they get wrong?

They got a couple things wrong. The famous saying attributed to Lord [John Maynard] Keynes -- I don't know if it's true or not -- but that markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay liquid. If you're not leveraged at all, if you just go out and, say, buy a stock or buy a bond and it goes down, you come back tomorrow. If it goes down the next day, you come back the day after that. And you just hang in there.

But if you're operating on somebody else's nickel, you don't have a tomorrow. If you're leveraged 10:1, and your asset goes down by 10 percent, you're wiped out. …

So one thing they got very, very wrong was thinking that not only would their bets be right, but they would always be recognized as right. It'd be never, ever a day when markets would say, "Hey, we're a little worried."

And they were fundamentally wrong in another sense, which is that markets were not as safe. There was this whole belief that recessions were done, the economic cycle was over, the Cold War was over. It was just going to sort of be happy sailing -- I mean, it sounds ridiculous now, but it wasn't ridiculous. It was a very seductive point of view after six or seven years of a gradually increasing, accelerating economy, mostly peace on earth, pre-9/11.

In their view, which they embodied in their trades, things are going to get better and better and better and better. We're done with history. It was [political scientist] Francis Fukuyama's thesis, if you could have canned that and put it into a financial trading engine.

And it turns out we weren't done with history.”

That was just a prelude to the market implosion that was the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

William White, a Canadian economist and central banker who was an economic advisor to the Bank of International Settlements, started warning Alan Greenspan to his face five years before the crisis struck that there was serious trouble brewing with volatile and explosive growth in mortgage debt. That was in 2003, the same year economist Robert Lucas delivered a lecture where he said

“My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.”

Five years later, the global financial system failed, and required trillions in investment that didn’t even bring it back to where it was.

Romer writes in The Trouble With Macroeconomics “Using the worldwide loss of output as a metric, the financial crisis of 2008-9 shows that Lucas’s prediction is a far more serious failure than the prediction that the Keynesian models got wrong. [in the 1970s.]”

If Lucas claiming his theories had forever ended financial disasters wasn’t hubris enough, the theory he won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1995 was for coming up with the “hypothesis” of “rational expectations,” which assumes that “individuals' actions are based on the best available economic theory and information.”

This is an absolutely insane assumption. But the levels of hubris here are off the charts. This is a guy who won a fake Nobel Prize for convincing people that it made sense, when you’re trying to account for and predict people’s economic behaviour, to assume that every single individual’s actions are based on the best available economic theory and information - and he couldn’t see the biggest international financial disaster catastrophe in decades coming, at all?

Clearly, this is a complete negation of that concept, because Lucas himself must not have been acting on the best available economic theory and information. He’s been hoist on his own petard, and we don’t know if it was the information, the theory or both to blame.

These are not scientific theories: they demand that so much is taken as given that the principles of neoclassical economics resemble unyielding articles of faith, which are strictly enforced.

Other economists from different disciplines - post-Keynesians and Modern Monetary Theorists recognize the existence and role of banks and private debt in the economy, which neoclassical / neoliberal economics do not.

In his outstanding book, Between Debt and the Devil, Adair Turner directly addressed the theoretical failures of these theories of finance. Turner is an academic with deep financial experience, as well as “hands on” experience acting as Chairman of the UK Financial Services Authority. He started the job in September 2008, just as the Global Financial Crisis was unfolding. He had to deal directly with the fallout based on reality, not theory.

“Two theoretical propositions in particular played a central role in the pre-crisis orthodoxy in both finance and macroeconomics— the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) and the Rational Expectations Hypothesis (REH).

The EMH defines an efficient financial market as one in which securities prices fully and rationally reflect all available information, and in which therefore price movements reflect newly available information rather than analysis of information already available or the impact of irrational sentiment. It suggests that the average investor —whether individual, pension fund, hedge fund, mutual fund, or bank dealing unit— cannot consistently beat the market. In particular it suggests that “chartist” analysis, which seeks to predict future stock price movements on the basis of past observed patterns, is a waste of time and resources: in securities markets investing, there is no free lunch.

Three arguments in turn explained why the EMH must apply. First, people are in general rational. Second, even if some people are irrational, their irrationality is random, with as many people likely to irrationally buy as irrationally sell: as a result, their behavior cancels out and leaves no impact on stock or bond prices. And third, even if there are enough irrational investors to produce divergences from efficient rational values, the action of rational arbitrageurs, who spot the divergences and trade to gain from the reversion to efficient rationality, will ensure that the reversion is swift. Moreover, extensive empirical evidence seemed to prove the theory correct. Michael Jensen, one of the creators of the EMH, claimed in 1978 that "there is no other proposition in economics which has more solid empirical evidence supporting it than the Efficient Markets Hypothesis."8

Meanwhile, the REH applied the assumption of human rationality to develop propositions also relevant to macroeconomics. It proposed that individual agents in the economy-be they individuals or businesses-operate on the basis of rational assessments of how the future economy will develop. The REH thus provided a theoretical underpinning for the EMH. But it also suggested that significant macroeconomic instability could only result from truly exogenous shocks (such as new resource discoveries or technologies), whose impact was unlikely to be very large, or from the harmful and unanticipated policy interventions of govern-ments. Provided governments and central banks pursued sensible rule-driven policies, the macroeconomic problems of the past must disappear.

Free financial markets, populated by rational agents, could not generate economic instability from within.

But real-world evidence and more realistic theory contradict both hypotheses. They show that human beings are not fully rational, and that even if they were, market imperfections could produce unstable financial markets that diverge far from rational equilibrium levels. They explain why market imperfections are inherent and unfixable, and why as a result market completion, financial innovation, and financial deepening-far from bringing us closer to the nirvana of efficient equilibria-can sometimes make economies less efficient and less stable.

All of this is important. The stuff that Mintz breezily calls finance theory has largely been obliterated when it gets out into the real world. That includes ideas like “the supply cost of equity increases as the personal tax on capital gains (and dividends) rises with income.”

In which we learn that people with more money are more likely to be investors.

Thus, the marginal investors providing equity finance to companies are higher-taxed investors such as those with gains of more than $250,000. Further, the corporate capital gains tax changes increased taxes on investment for large, medium, and small non-financial companies.

9 Yet Another Gross Miscalculation

Mintz continues:

“Impact on the economy

Overall, the capital gains tax hike has a significant impact on both the incentive to hold capital in Canada and employment. At least half of the impact is due to the increase in the corporate capital gains tax rate.

The budget’s capital gains tax hike increased the tax-inclusive cost of capital for large companies by 5 percent (according to estimates by Philip Bazel and me using our marginal effective tax rate model). Based on conventional assumptions that an increase in the tax-inclusive cost of capital by 10 percent causes the capital stock to fall by 7 percent, I estimate that Canada’s capital stock would fall by $127 billion. Employment would permanently decline by 414,000. To put this in terms of its impact on unemployment, the capital gains tax hike would increase unemployment from 1.5 to 1.9 million Canadian workers as of August 2024. GDP will fall by almost $90 billion and real per capita GDP by 3 percent.

While the impact of the capital gains tax hike is not catastrophic, it is meaningful. It’s another hit on Canada’s productivity and economic growth on top of other tax increases and more important, regulatory obstacles to investment.

As I’ve been pointing out above, the whole problem with the capital gains is that the gains had nothing to do with productive investment or job creation. It’s about borrowing money to bet that the price of the house you buy will go up faster than your monthly payments.

What has caused our productivity crisis is that whenever there is a recession or a crisis and “real economy” businesses fail and people lose their jobs, the reflexive response from central banks and government is to drop interest rates to juice the economy, but it doesn’t go to building new industry. It goes to driving up the price of assets like real estate and stocks.

So Canada, the UK, parts of the US and other developed countries in Europe have economies where, because of these same neoclassical theories in government, which is that the modern economy, the consumer is supposed to supply all the money for that new growth, by taking on more personal debt.

It’s very important to distinguish between different parts of the economy. It’s usually very binary and opposite. “Labour vs employer”, for example, or “corporations vs workers.”

One of the biggest and most important parts of the economy is missing from this picture - the FIRE sector. Finance, Insurance and Real Estate.

So you should at least recognize that the private economy has three sectors, not just two. You have “real economy” businesses, which is industrial capitalism; you have workers, and you have finance.

The thing that defines the “real economy” people are exchanging money for something that isn’t money. Food, gas, services, entertainment, services. In the FIRE sector, it’s money for money.

This distinction is incredibly important for better understanding how the different sectors in our economies actually interact.

That’s because when people talk about “inequality” we talk about “ordinary people” vs billionaires, or vs corporations. What’s missing from that is that it is not just people and workers who have been stagnating and struggling, so do real economy businesses.

This is why it’s harder for Canadian businesses to create good jobs. It’s not because of the government overhead, it’s not. The Fraser Institute misleads people about taxes. It’s because of the private debt overhead. The enviable debt-to-GDP ratio we have comes at the price of massive borrowing on the part of individual Canadians so they can afford education and housing.

What about neutrality?

It is not just tax rates that affect economic growth and productivity. Tax distortions that result in the misallocation of resources also undermine productivity when capital resources are misallocated in the economy. With capital gains taxation, however, the impact on distortions is rather complex.

The strongest argument made for increasing the capital gains tax from one-half to two-thirds of the ordinary personal income tax is neutrality in financial structures. As the federal-provincial corporate income tax rates have fallen from 43 percent to 26 percent today, the dividend tax credit was reduced. This resulted in dividend tax rates rising since 2000 while the capital gains tax rate remained unchanged at one-half of the personal income tax rate. When dividends are taxed more heavily than capital gains, it encourages companies to pass out income to investors in the form of capital gains rather than dividends. This is one distortion addressed by the budget, although limited to capital gains in excess of $250,000.

With the corporate capital gains tax, however, a different distortion arises in that corporate capital gains are taxed more heavily than inter-corporate dividends (the latter are exempt from taxation to avoid double taxation on profits distributed from one corporation to another). When corporate capital gains are more heavily taxed than dividends, companies are encouraged to structure inter-corporate payments as dividends rather than capital gains.

Thus, increasing the corporate capital gains tax rate widens the distortion between dividend payments and reinvested earnings at the corporate level. As shown in a recent European study, the corporate capital gains tax distorts the market for corporate control by discouraging acquisitions and mergers, resulting in a foregone deal loss of $1.1 billion in 2013 for Canada.

The article Mintz cites says:

“We find that a one percentage point increase in the capital gains tax rate reduces acquisition activity by around 1% annually. For the United States, this implies unrealized synergy gains of $9.3 billion each year due to capital gains taxes.

Aside from the fact that there is no such thing as a “synergy gain” the very nature of mergers & acquisitions is that they are, by their very nature not about the creation of new value.

M & As invest capital in existing businesses with the view to finding “efficiencies” which amounts to combining companies and removing the people and facilities that are redundant in the new structure. The more an investor pays for an asset, the harder it is to recoup the investment.

Mergers and acquisitions can mean reduced competition, greater concentration of ownership and returns, fewer jobs and higher prices, because corporations can lever their bargaining power and squeeze concessions from suppliers and customers alike.

The other is that instead of investing in productive industry - and capital that would allow workers to be more productive and earn more money - M & As are being fuelled by access to “easy money”, and instead of return to equity from dividends, speculators are looking to make money from increases in the stock price.

When interest rates drop, not only to financial institutions start to offer credit to NINJA clients - “no income, no job, no assets” the credit that is offered to clients who do have income and assets is astronomical. The same debt-fuelled speculation that drives up the price of real estate assets is used to flip companies, instead of houses, and drive up the price of stocks.

As Roger L. Martin, former dean of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management has written, it is not being based on real-world, real-economy improvement, which are difficult to achieve. It is based on financial engineering, where gains are being achieved because investors are replacing stable equity with volatile debt in order to increase returns.

This is what drives manias and financial crashes - people borrowing to speculate on non-productive assets.

Further, the budget introduces a new distortion in the tax system. In the past, the capital gains tax at the corporate level was the same as that paid by individuals. The reason for this policy was to minimize the incentive to hold assets at the corporate or personal level to avoid capital gains taxes. For example, if there were no corporate capital gains tax, an investor could avoid capital gains taxes by selling real estate assets held by the corporation rather than selling them as an individual.

The 2024 budget introduces a lower tax rate on capital gains at the individual level (due to the $250,000 exemption) compared to the corporate level. This will encourage investors to hold equities directly rather than at the corporate level. While this might seem innocent, it can create distortions in the allocation of capital. For example, corporate assets are subject to limited liability and can be jointly held by many investors. By pushing assets to be held at the individual level, some of the benefits of incorporation can be lost.

Further, the increase in the capital gain tax rate encourages investors to hold on to assets longer rather than replace them with assets that provide superior returns to equity. Capital gains taxes also discourage risk-taking since the government taxes the nominal gains but does not provide a refund for potential losses.

Again, Mintz is arguing against long-term value investing in productive business in favour of short-term speculative investments in non-productive real estate.

Taking into account all these considerations, the 2024 budget reduces some but increases other tax distortions. Productivity is likely reduced simply by raising taxes on capital investment.

Mintz has to phrase it as “Productivity is likely reduced” because he’s not presenting evidence for it.

Key takeaways

Overall, the increase in the capital gains tax rate at both the corporate and personal level is expected to discourage business investment and employment, unlike that claimed in April’s federal budget or by the IMF. I find that the increase in the capital gains tax rate will reduce Canada’s GDP by $90 billion, real per capita GDP by 3 percent, its capital stock by $127 billion, and employment by 414,000. This is not a trivial loss to the Canadian economy.

Jack Mintz is a Distinguished Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and the President’s Fellow of the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary.

Mintz’ article was published on The Hub Canada, and reprinted at the MacDonald Laurier Institute, and it is being repeated by Conservative Members of Parliament, and it’s all based on conjecture.

This work does not rise to the level of research. It is a propaganda piece based on a string of assumptions that are imaginary.

When people in Canada talk about misinformation, or fake news, or the right of the public to know, or propaganda from foreign entities, or from Fox News in the U.S., the political reality is that think tanks like MLI, the Fraser Institute release reports that are based on economic dogma that amounts to a secular religion based on imaginary forces and fantasy.

Mintz’s piece was made possible by the “Centre for Civic Engagement” which is another think tank.

This is what Paul Romer said when concluded his paper “The Trouble with Macroeconomics” about the failure of economics to respect the norms of science.

“Several economists I know seem to have assimilated a norm that the post-real macroeconomists actively promote – that it is an extremely serious violation of some honor code for anyone to criticize openly a revered authority figure – and that neither facts that are false, nor predictions that are wrong, nor models that make no sense matter enough to worry about.

A norm that places an authority above criticism helps people cooperate as members of a belief field that pursues political, moral, or religious objectives. As Jonathan Haidt (2012) observes, this type of norm had survival value because it helped members of one group mount a coordinated defense when they were attacked by another group. It is supported by two innate moral senses, one that encourages us to defer to authority, another which compels self-sacrifice to defend the purity of the sacred.

Science, and all the other research fields spawned by the enlightenment, survive by "turning the dial to zero" on these innate moral senses. Members cultivate the conviction that nothing is sacred and that authority should always be challenged. In this sense, Voltaire is more important to the intellectual foundation of the research fields of the enlightenment than Descartes or Newton…

Some economists counter my concerns by saying that post-real macroeconomics is a backwater that can safely be ignored; after all, "how many economists really believe that extremely tight monetary policy will have zero effect on real output?"

To me, this reveals a disturbing blind spot. The trouble is not so much that macroeconomists say things that are inconsistent with the facts. The real trouble is that other economists do not care that the macroeconomists do not care about the facts. An indifferent tolerance of obvious error is even more corrosive to science than committed advocacy of error.

It is sad to recognize that economists who made such important scientific contributions in the early stages of their careers followed a trajectory that took them away from science. It is painful to say this so when they are people I know and like and when so many other people that I know and like idolize these leaders.

But science and the spirit of the enlightenment are the most important human accomplishments. They matter more than the feelings of any of us.

You may not share my commitment to science, but ask yourself this: Would you want your child to be treated by a doctor who is more committed to his friend the anti-vaxer and his other friend the homeopath than to medical science? If not, why should you expect that people who want answers will keep paying attention to economists after they learn that we are more committed to friends than facts.

Many people seem to admire E. M. Forster’s assertion that his friends were more important to him than his country. To me it would have been more admirable if he had written, "If I have to choose between betraying science and betraying a friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my friend."

What Romer is describing is corruption - a profession that will not state the truth in public or even abide by the norms of science, in order to protect the status quo.

Neoclassical economics is best understood as an ideology that has become the secular religion of the state. In many countries, and adherence and discipline is maintained through propaganda, accusations of heresy, punishment and excommunication. There are laws and treaties that outlaw any other form of economic thought, when the imagary basis of orthodox neoclassical economics cannot be questioned, because these theories and formulas are considered to be infallible - as is the market.

Effectively, neoclassical and neoliberal economists are in the position of the Indulgence-sellers of the Catholic Church. An enlightened reformation is long overdue.

-30-