Quantitative Easing Invalidates Supply-Side Economics. Another world is possible.

If you have to save to invest, why did central banks have to create $20-trillion in new money to pump up the economy?

QE invalidates the current Neoclassical/ Neoliberal Economic Paradigm

If you’ve seen the news about central banks, you may have heard the term quantitative easing, or QE. It’s been widely used in the last 15 years or so, especially since the Global Financial Crisis.

For many years, central banks would either stimulate the economy with lower interest rates - which means bigger loans and more spending, or raising interest rates to cool the economy with smaller loans, and less spending. That’s the simple way central banks see the economy as working it.

However, if interest rates are already low - close to zero, or “at the lower bound” - and the economy is still struggling, if central banks can’t lower interest rates any further, and banks still aren’t able to lend more because they’re running short on cash - are having a “liquidity’ crisis, then the central bank will create new money out of thin air and giving it to banks in exchange for taking some of the banks assets off of them.

From Investopedia:

What Is Quantitative Easing?

Quantitative easing (QE) is a form of monetary policy in which a central bank, like the U.S. Federal Reserve, purchases securities in the open market to reduce interest rates and increase the money supply.

Quantitative easing creates new bank reserves, providing banks with more liquidity and encouraging lending and investment. In the United States, the Federal Reserve implements QE policies.

During the pandemic, Central Banks around the world printed about $8-trillion. After the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 the amount printed was more. Canada’s banks were bailed out by $114-billion and backstopped by the Bank of Canada. In the U.S. there were trillions of dollars printed, as there were trillions of Euros printed the EU. The Bank of England also printed billions and billions of pounds.

This is how Paul Beaudry of the Bank of Canada explained QE as working.

Beaudry’s explanation of the mechanics start involves calling it a “reverse auction” which is characteristic of the needlessly weird language around finance. An auction is selling. The reverse of auction is buying. So, it’s buying assets.

“When the Bank buys government bonds of a given maturity, it bids up their price. This, in turn, lowers the rate of interest that the bond pays to its holders. When the interest rate on government bonds is lower, this transmits itself to other interest rates, such as those on mortgages and corporate loans. This stimulates more borrowing and spending, which helps inflation move closer to the 2 percent inflation target. So, as you can see, even when the overnight rate can no longer be reduced, the Bank can still affect longer-term interest rates by using QE.

If we buy $100 million of government bonds from Bank A, we pay for them by issuing what are called settlement balances. These appear as deposits with the Bank of Canada.

Just like commercial banks consider deposits as a liability that they owe to their clients, settlement balances are a liability the Bank of Canada owes to the commercial banks. We pay interest on them at our deposit rate, which moves one-for-one with our policy interest rate.

So to recap, when we perform our QE operations, we buy government bonds from financial institutions and issue liabilities—in the form of settlement balances—to pay for them.

It’s important to note here that settlement balances are a normal part of central banking operations. Being able to issue settlement balances is a privilege that only central banks have. We use this ability carefully to fulfill our mandate of promoting the economic and financial welfare of Canada and Canadians.”

So, the Bank of Canada has an account for a bank and it creates money in it, which only it has the power to do.

What QE is doing for banks is an injection of equity in order to compensate for investments in lending gone wrong.

I know this gives people headaches, but it really is the same as creating an IOU, and when an IOU is cashed in, it is ripped up.

Money is much more like files and data in computer memory, which can be created out of nothing and wiped out again. This does not mean it is meaningless, any more than numbers or words are meaningless just because we can erase them after we’ve written them down.

This is why the obsession with money within an economy being “backed” by an item of value, like gold, misses the point. The value of a piece of paper or plastic or metal that is turned into money depends on the symbol on it, not the intrinsic value of the material it is printed on. Money is something we use to get other people to do things: it is a way of instructing, organizing and even controlling people and keeping track of social obligations that is legally enforced.

Money is a form of information, and information can be used to control as well as communicate. It’s something you use it to get other people to do stuff - release property to you, provide a service. Because people might do anything, civil and criminal laws regulate how money can be used.

And it is all within a given currency. Having your own currency - monetary sovereignty - means that if you need American money to get Americans to do what you want, Canadian money to get Canadians to do what you want.

Yes, this is very different from the way we think about money, and that is the point. It is not a system with piles of cash, coins and gold bullion sitting around. It is a dynamic information system where money is being created and deleted, in highly specific ways. Using terms like “liquidity” and “flows” ignores that what is happening in a money transaction is that when money is transferred from account to account, it is deleted from one account as it is written into another. This specificity matters, and it is not new. This is how money has always worked.

Money creation in the modern economy

Current economic theory is sloppy and imprecise because it groups together completely different types of money flows which originate from different sources and flow to different constituencies.

We should separate out three separate streams of money creation for an economy with its own currency, because they have very different impacts.

Economists, including very prominent ones, will refer to “printing money” in ways that are completely sloppy and inaccurate. It’s common to refer to any kind of deficit spending by government as “printing money” and suggest that it must be causing inflation because they wrongly believe it is increasing the amount of money in the economy, when it is not.

We can talk about three:

Federal Government Fiscal spending, which is spent on services, public investments, transfers to individuals

The special case of Quantitative Easing, which creates new bank reserves so banks can lend more

Private banks expanding the money supply by extending private credit, which varies based on regulation and interest rates set by the central bank.

Empirical studies of the mechanics of money creation flatly contradict the theories and assumptions that are guiding current decision-making.

Federal Government Fiscal Spending

Recent empirical studies of finance being allocated by the UK government shows that government’s fiscal spending is not financed up front by taxation or by issuing debt - the spending occurs first, the taxation follows and the debt issuance can also be seen as private investors looking for a safe return. A 2022 working paper from the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose analyzed the actual processes of how spending occurs in the UK government.

“We find, first, that the UK Government creates new money and purchasing power when it undertakes expenditure, rather than spending being financed by taxation from, or debt issuance to, the private sector.”

They add that when investors buy government debt, it is because the government is acting as a bank where investors can keep their money safe - because a government that has its own currency and the capacity to create money can always pay its bills. This is a feature, not a bug.

The special case of Quantitative Easing, or QE.

This is a central bank creating money, and the money is going to financial institutions to create new reserves. This is actual, new money creation, and despite the massive sums, it is actually the kind of policy tool you have behind a glass and that you smash and only take out in an emergency.

So, if you are one of Canada’s banks when you do your online banking with the Bank of Canada, all of a sudden there is $25-billion in there. This is exactly what happened with several banks in Canada in 2008-2009, and is the reason that Canada’s banks did not fail. It was not Canadian caution and prudential regulation. The Bank of Canada, the Federal Reserve and the Canadian government created money in Bank of Canada bank accounts for banks to access, because the assets that made up their reserves were collapsing in value.

To repeat - QE is about shoring up and creating new reserves for financial and other institutions, on the claim that they will stimulate the economy by extending more credit - by overpaying for assets.

That is what Beaudry appears to be saying when he says that when the Bank of Canada buys these government bonds, they “bid up the price.” They’re paying more than they are worth for them.

So, publicly owned central banks, which are a part of government but independent from political influence, are creating new money for private banks to lend more in a crisis, when interest rates are already as low as they will go. This is new money. It is being created by government, and going to private banks, and the banks are getting more for the bonds they are selling than they are worth.

The rationale for this is the ideological belief that the private sector and the market will do a better job of allocating capital, which is beyong ironic. First, Bank QE happens in response to private sector’s investments collapsing. Second, the new investments made possible by Bank QE are overwhelmingly used to drive up the price of existing assets - not creating new value.

As mentioned above, “Quantitative easing creates new bank reserves.” so they can lend more.

It’s important to note, however that banks don’t lend their reserves. When the central bank creates that money, it’s to purchase assets from the bank: government bonds, or securities made of up mortgages that were part of the bank’s reserves.

What’s happening with QE is that those assets in the private banks’ reserves are being replaced with cash. While this does prevent a so-called “bank run” because the bank’s ability to function is directly related by the ratio of its reserves to its lending, banks don’t lend out those bonds in the form of mortgages. Banks extend credit, and we’ll get to that shortly.

The way that QE works invalidates “supply-side” economics, which says that you have to save to invest. QE creates money in order to invest it, which then flows through the economy and returns to the government in the form of taxes.

This has a number of very important consequences for our current economic theories, and the entire neoclassical/neoliberal/supply side/fiscally conservative economic theories that have dominated the profession since the 1970s, including fiscal, tax and monetary policy that are based around this principle - that we have to push more to those that already have it in order to invest - when they are already getting above asking price in newly created money from central banks to keep their assets from dropping in value.

Supply-side economics falls at the first hurdle. You do not have to save to invest, and the economy is getting newly created money to invest.

The fact that newly created money is going to keep up bank reserves is extremely important in multiple ways.

The mechanics of this matter. First, this is considered a “stimulus” for the market - but this is an economic stimulus that is based on people and businesses borrowing more. So, it is not ‘government spending” on programs. The idea is that if people borrow privately and spend, it will be more market-based and efficient than a government program.

However, it is a stimulus with colossal differences in distributional impact on income and wealth for individuals, businesses, and it is all in the form of private debt. Monetary stimulus from manipulating interest rates alone amplifies differences in wealth and income to an incredible degree. People who have less money and property pay higher interest rates and vice versa. That is self-evident. Preferential lending will be based on pre-existing concentrations of wealth, with the highest barriers for those with the least resources.

Also - and this is really important: QE is not money that is being spent (or created) by any elected official. It is not money that is being spent on any kind of public investment.

This is dealing with private banks and investors. And really, it’s as if you were a homeowner, and the value of that asset is dropping, so the government steps in and takes the debt off your hands, and gives you newly printed cash-equivalent for it.

So, if there is a chicken and the egg argument, “Which came first, government money or taxes?” the answer is “Government money.” That is where money comes from. That is why cash has the face of the head of state on it. That is why we have legal tender.

QE makes it absolutely clear that government is creating money out of thin air so that private investors can invest.

People will sometimes ask whether it is possible to run government without any taxes, the answer is yes, with a giant proviso: while governments do not need taxes to create money to start the economy going again, we do need taxes to keep the economy going in a way that’s stable.

Central banks truly do have the capacity to create money without limit, which is exactly why that capacity is so strictly regulated and controlled.

When you mention this, people who have opinions about such things usually freak out, and they immediately invoke the hyperinflation in Germany in the 1920s, because it was associated with government moneyprinting and the idea that it led to the rise of fascism and extremism in Germany. As I have written elsewhere, none of this is true.

So, the response to talking about the capacity of central banks to create money, which accurately speaking, is unlimited, is often a kind of panic and horror, because, like true believers who meet an infidel, they imagine that without these particular guidelines - and these alone - there will certainly be a total lack of constraint, and no end to the financial equivalent of sinning.

It’s worth pointing out that central banks have been doing this, and we need to put it (and other government spending) in perspective.

When we are talking about QE, we are talking about only one source of money being newly (freshly?) created in the economy. While these numbers are absolutely colossal - hundreds of billions or trillions of dollars, pounds, Euros, they may still sometimes be small in comparison to the total economy, as well as total private lending.

People will say, “well, this new money that’s going in is what is causing inflation” may seem like it makes sense, except that money itself is not one big pool. That’s a mathematical convenience for economists.

All that money is in millions of separate bank accounts - personal, corporate government, charities, and so on. It’s not a pool that sloshes around. Just because money’s going into someone’s bank account doesn’t mean you’ll see a penny of it, and the disparties in ownership in any economy where there is a billionaire on one hand and a homeless person on the other is colossal. Money does not flow.

It is important to understand that fiat money can be and is created out of thin air, right now, and while various cranks will complain about it, if you want a functioning modern economy, you need to have an entity - one entity - that has the capacity to do this.

And if you think it’s weird that money can be created out of thin air consider that we can all write IOU’s. There are cheques, money orders and we now transfer money electronically all the time. A store can “extend credit” to a customer and run a tab.

It’s vitally important to understand that not only can that money be created out of thin air, it can go back to thin air again. It can be created and deleted, and so can real value. Paper money can be printed and burned. A house can be destroyed in a flood.

Private banks create “credit-money” by extending credit, based on interest rates set by central banks

In 2014, analysts at the Bank of England wrote a paper called “Modern Creation in the Modern Economy” that explained that that commercial banks expand the money supply as well - in a way that is similar, though not exactly, to Central Banks. Commercial banks create new money, within a specific framework, by extending credit.“the majority of money in the modern economy is created by commercial banks making loans. Money creation in practice differs from some popular misconceptions — banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them, and nor do they ‘multiply up’ central bank money to create new loans and deposits. The amount of money created in the economy ultimately depends on the monetary policy of the central bank. In normal times, this is carried out by setting interest rates. The central bank can also affect the amount of money directly through purchasing assets or ‘quantitative easing’.”

… “Broad money is a measure of the total amount of money held by households and companies in the economy. Broad money is made up of bank deposits — which are essentially IOUs from commercial banks to households and companies — and currency — mostly IOUs from the central bank. Of the two types of broad money, bank deposits make up the vast majority — 97% of the amount currently in circulation. And in the modern economy, those bank deposits are mostly created by commercial banks themselves.”

As the Bank of England explains

“Commercial banks create money, in the form of bank deposits, by making new loans. When a bank makes a loan, for example to someone taking out a mortgage to buy a house, it does not typically do so by giving them thousands of pounds worth of banknotes. Instead, it credits their bank account with a bank deposit of the size of the mortgage. At that moment, new money is created. For this reason, some economists have referred to bank deposits as ‘fountain pen money’, created at the stroke of bankers’ pens when they approve loans.”

This is not fiat-money like the kind that is created by government. Banks are “extending credit” and this credit-money is 97% of the money in circulation.

If you want to understand how this can possibly work, it is for a couple of reasons.

One, which is relatively easy to wrap your head around, is because the credit money being created is going to purchase an asset - a home, so if the borrower defaults, the bank gets a valuable asset they can then sell to recoup, and they are being charged interest.

This description of money creation contrasts with the notion that banks can only lend out pre-existing money... Bank deposits are simply a record of how much the bank itself owes its customers. So they are a liability of the bank, not an asset that could be lent out. A related misconception is that banks can lend out their reserves.

Reserves can only be lent between banks, since consumers do not have access to reserves accounts at the Bank of England.

What a bank is saying is “this person is good for this amount of money”, which requires a promissory note from the borrower - a mortgage, which is paid back with interest.

As that money is paid back, the interest on top of the principal is what the bank actually earns, but the credit money that has been extended is gradually “deleted” or destroyed.

This is a significant challenge in the way we think about money, but again, it is because money is not a series of fixed material objects. Just as it can be created out of nothing at the stroke of a pen, it can be erased again at the stroke of a pen.

So, the repayment of these bank loans gradually deletes the credit money that was extended.

Just as taking out a new loan creates money, the repayment of bank loans destroys money. For example, suppose a consumer has spent money in the supermarket throughout the month by using a credit card. Each purchase made using the credit card will have increased the outstanding loans on the consumer’s balance sheet and the deposits on the supermarket’s balance sheet. If the consumer were then to pay their credit card bill in full at the end of the month, its bank would reduce the amount of deposits in the consumer’s account by the value of the credit card bill, thus destroying all of the newly created money.

Banks are therefore in a balancing act of continually extending and deleting (or destroying) credit money - and the Bank of England makes it clear, there are limits.

Although commercial banks create money through their lending behaviour, they cannot in practice do so without limit. In particular, the price of loans — that is, the interest rate (plus any fees) charged by banks — determines the amount that households and companies will want to borrow. A number of factors influence the price of new lending, not least the monetary policy of the Bank of England, which affects the level of various interest rates in the economy.

When central banks drop interest rates to “stimulate” the economy, it alters the lending landscape: more people qualify for loans, and they can be larger - so banks create more credit-money. When they drop interest rates to “cool off” the economy, fewer people qualify and loans shrink.

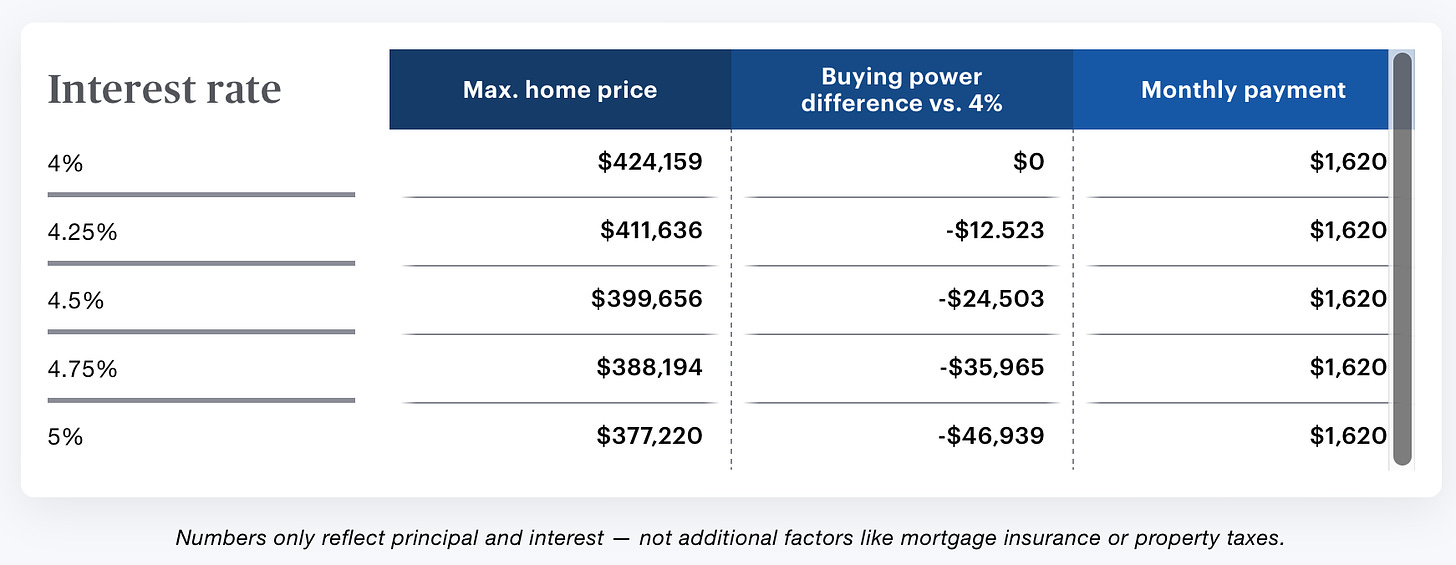

The change of a single point in interest can interest or lower the size of a mid-range North American mortgage by nearly $50,000.

This practice - of altering interest rates so that banks increase lending - is considered “money printing” by economists. (!)

While it is supposed to stimulate the economy as a whole and encourage people to take out loans to start new businesses the credit is being created as mortgages, which drive up the price of new and old housing alike. Instead of creating new assets and new value in productive industries- which would not be inflationary - individual households are taking on hundreds of billions of dollars in new debt to drive up the price of existing assets - especially housing.

The result in a number of countries - Canada, the UK, the US, New Zealand - is a massively inflated housing market underpinned by personal debt that is so high that it slows the economy, because so much income is being directed to debt servicing.

In Canada, household debt, held by families in the form of mortgages, is much higher than the public debt held by government.

In December 2023, the federal government’s debt was CAN $1.173-trillion.

This month, October 2024, Canadians’ household debt was CAN $2.98 trillion.

This household debt is mostly mortgages, and has mostly been used to drive up the housing market since 2009. It is a direct consequence of the Bank of Canada (and other central banks around the world) using “monetary stimulus” and QE to pump up one sector of the economy - the FIRE sector, of finance, insurance and real estate.

This boost fuels the FIRE sector - as well as tax revenues. Instead of fiscal investments in infrastructure, innovation, R & D and investments in productive, it has driven up the price of existing assets - stocks and property - around which there is already concentrated ownership. It directly makes the rich richer and the poor poorer.

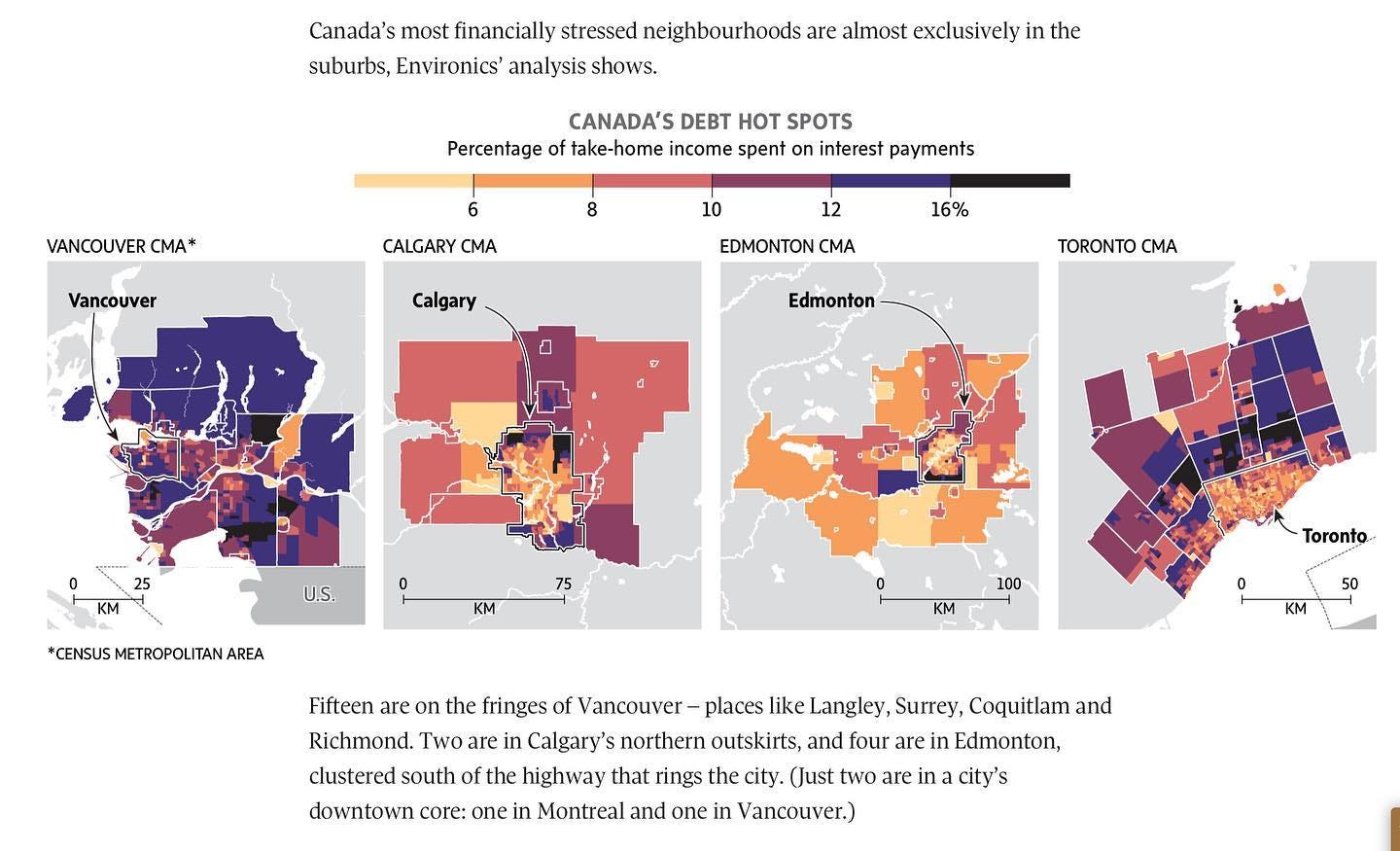

In 2019, the Globe and Mail ran an important article “How Canada’s suburban dream became a debt-filled nightmare” It was published in the first days of the General Election, and didn’t get the attention it deserved.

It showed maps of Canadian cities, showing how much take-home income people were spending on mortgage interest. In many suburbs - especially around Vancouver and Toronto, but in other cities as well, people are paying up to 20% of their income on mortgage debt.

"Fifteen are on the fringes of Vancouver - places like Langley, Surrey, Coquitlam and Richmond. Two are in Calgary's northern outskirts, and four are in Edmonton, clustered south of the highway that rings the city. Just two are in a city's downtown core: one in Montreal and one in Vancouver.”

That was in 2019.

That fall, in September 2019, there were also signs of financial instability - because debt levels around the world were so high.

That crash was prevented by the emergency pandemic response. During the pandemic, central banks created billions of dollars in QE - to create new reserves for banks - and lowered interest rates, to encourage more lending.

While there were also important fiscal measures, they were dwarfed by the tsunami of easy money this unleased, which went into driving up the price of housing, which was aided and abbetted by provincial governments who lifted evictions.

This is what drove up the price of housing, while adding to people’s individual debt burdens for education and for housing, which is a necessity of life.

The problem we are facing is not an inflation crisis caused by government spending. The inflation of 2022-23 was largely due to profit-taking.

These levels of private debt are a threat to the stability of the entire financial system, and that is why the decision to hike rates, as central banks around the world have, it is driving the crisis and making it worse, not better.

In July 2022, Edward Chancellor warned

“It will turn out to be largely impossible to normalize interest rates without collapsing the economy…

By aggressively pursuing an inflation target of 2% and constantly living in horror of even the mildest form of deflation, they not only gave us the ultra-low interest rates with their unintended consequences in terms of the Everything Bubble. They also facilitated a misallocation of capital of epic proportions, they created an over-financialization of the economy and a rise in indebtedness. Putting all this together, they created and abetted an environment of low productivity growth.”

So trickle-down economics isn’t right. So what?

The fundamental reality is that the economy and money function in a way this is different than what we have been told.

We are having artificial constraints and limits placed on us by adherence to an economic model that is failing, in part because it not even close to being an accurate model of the economy. It is a model based on ideas about the economy - many of them political assumptions.

These other accounts are a modern form of Keynesian economics. And it’s important to emphasize, this is not proposing a new system of policies for governments to start doing. It is proposing new and better explanations for what they are doing right now.

These ideas of money creation are not new. Keynes, Schumpeter and Milton Friedman all recognized that commercial banks extended credit and created money.

In 2016, eight years after the Global Financial Crisis, a new crisis is sweeping the globe: Global Trumpism. As Political Scientist Mark Blyth put it, “The era of neoliberalism is dead, the era of neonationalism has just begun.”

The good news

The fact that our governments are incapable of dealing with crises is not just political, it is ideological. Right now in the UK, Labour is making terrible cuts that are simply unnecessary. Canada and the U.S. and many other countries are facing far-right conservative parties because policymakers and central banks keep tightening the thumbscrews, in defiance of evidence and reality.

The inequality generated around the world by globalization has generated anger not just at elites in specific countries, but at the countries that lead the global elite. The system is broken because the ideas that drive neoliberalism have failed. Joseph Stiglitz has said so, Paul Romer has said so. Angus Deaton has said so. William White has said so. There are also plenty of other economists who have been saying so for a long time, like Marianna Mazzucatto, Stephanie Kelton, Dr. Steve Keen and others.

It is all driving unrest, with citizens across the world are turning on each other and their elites.

Extraordinary crises require an extraordinary response, yet all we have is the same two “left-right” options: more public debt and higher taxes on the one hand, or austerity and more private debt on the other.

There is a sensible, peaceful, sane path of economic reform and relief that can stabilizes the economy and put the private sector back on its feet. The crisis we are facing is due to the result of the creation of too much private debt.

Unlike fiat money created by government or central bank QE for bank reserves or government taxing and spending, the demand that credit-money places on the borrower grows based on an algorithm of compound interest that continually doubles.

We have replaced stable equity with unstable debt, in people’s personal lives as well as in corporations. There’s a saying that “Debts that can’t be paid, won’t be.” The question for policymakers is to come up with a plan to make sure that if defaults are inevitable, that steps are taken to mitigate the harm, and keep risks from spreading. Orderly, structured defaults and debt renegotiation is preferable to chaotic defaults.

What is required is to reverse this process, and replace debt with equity by restructuring and reducing debts. William White has argued that is essential, here:

“These shortcomings point to the need for explicit debt restructuring or even outright forgiveness. However, the administrative and judicial mechanisms needed to do this effectively are lacking and need to be put in place. In recent years, the Working Party on Macro-Economic and Structural Policy Analysis at the OECD and the Group of Thirty have published extensive documentation of current shortcomings and suggestions for improvements. Procedures for resolving debt problems in the corporate and household sectors need improvement. Not least, “zombie” companies must be restructured rather than be given “evergreen loans” as is currently the case. Indeed, measures taken to reduce the economic costs of the pandemic have sharply worsened this problem. Procedures for resolving financial sector insolvencies are even more inadequate. The problem of banks that are “too big to fail” must be dealt with definitively. We also need an accepted set of principles for the restructuring of sovereign debt.

Ari Androcopoulos has written a paper, “The Relationship Between High Debt Levels and Economic Stagnation, Explained by a Simple Cash Flow Model of the Economy” which not only recommends helicopter drops, but explains how Central Banks’ policies of increasing debt and raising asset prices has contributed to our current crisis. One important consequence is that private, not public debt is contributes far more to economic stagnation than believed.

Economist Steve Keen has argued for a “people’s QE” helicopter money as a solution out of the crisis, before another debt crisis engulfs us.

He suggested direct depositing money straight into bank accounts, with individual households in the economy getting a share to avoid moral hazard. Keen’s idea is that those who have debts can pay them down, relieving creditors as well. Those without debt can spend, save or invest. As spending drives growth, taxes help restore government balance sheets.

There is a sensible, peaceful, sane path of economic reform and relief that can stabilizes the economy and puts the private sector back on its feet.

The crisis we are facing is due to the result of the creation of too much private debt. Unlike fiat money created by government or central bank QE for bank reserves or government taxing and spending, the demand that credit-money places on the borrower grows based on an algorithm of compound interest.

What is required is to reverse this process, and replace debt with equity.

Another paper by Josh Ryan Collins, “Is Monetary Financing Inflationary? A Case Study of the Canadian Economy, 1935–75” showed that the Bank of Canada played a major role not just in helping Canada escape from the Depression, working with the government to provide “significant direct or indirect monetary financing to support fiscal expansion, economic growth, and industrialization.” Inflation, the great fear of money creation, was not found to be a serious concern in peacetime: it was more strongly correlated with wartime inflation.

He writes:

“there always exists – even in a permanent liquidity trap – a combined monetary and fiscal policy action that boosts private demand – in principle without limit. Deflation, ‘lowflation’ and secular stagnation are therefore unnecessary. They are policy choices.”

(Emphasis mine.)

Add to this new research questioning the definition of supply and demand, which imply that “measures to raise demand in a recession – fiscal stimulus, perhaps, or monetary easing – could make productivity growth faster too, giving the economy a boost not just in the short term, but for many years.”

The objections to such a program is based on the very economic theories that have created and extended the current crisis, and make it impossible to resolve. Neoclassical / neoliberal economics are based in what are superstitious taboos, not evidence.

The point of this is not that money can be created for follies. The point is that if we can actually do something - we have the people, know-how and resources - the capacity to do it without driving up inflation is the limitation, not money.

In 1942, Keynes delivered this radio address:

Anything We Can Actually Do, We Can Afford

Let us not submit to the vile doctrine of the nineteenth century that every enterprise must justify itself in pounds, shillings and pence of cash income … Why should we not add in every substantial city the dignity of an ancient university or a European capital … an ample theater, a concert hall, a dance hall, a gallery, cafes, and so forth. Assuredly we can afford this and so much more. Anything we can actually do, we can afford. … We are immeasurably richer than our predecessors. Is it not evident that some sophistry, some fallacy, governs our collective action if we are forced to be so much meaner than they in the embellishments of life? …

Yet these must be only the trimmings on the more solid, urgent and necessary outgoings on housing the people, on reconstructing industry and transport and on replanning the environment of our daily life. Not only shall we come to possess these excellent things. With a big programme carried out at a regulated pace we can hope to keep employment good for many years to come. We shall, in fact, have built our New Jerusalem out of the labour which in our former vain folly we were keeping unused and unhappy in enforced idleness.

This is not just about government. It is about economic renewal that combines relief and investment that is essential to move forward, because we are being held captive by an economic ideology that takes evidence and logic less seriously than a medieval theologian. The biggest challenge is overcoming these medieval beliefs - which are returning up to a medieval economy and a medieval political system.

But if we can offer a reformation, a new and more enlightened era is possible.

-30-

Dougald this another great article and has provoked me to become a paid subscriber.

Direct payments to individuals make a lot of sense to me, and I would argue in favour of a universal basic income. There are a few of reasons why.

The first is that the last 50 years has seen a systematic government-abetted transfer of wealth to corporations from wage earners as wages have lagged productivity growth while profits have soared.

The second major reason to support UBI is because of the inequality generated by the inflation in asset values documented in your post. A broad segment of society has been disadvantaged by that, and it needs to be addressed.

The other major reason is the transition that is happening in the labour market, which is the displacement of human labour by AI. We are just at the beginning stages of it, where call centres are being eliminated but in a short period of time there is going to be a huge impact on the amount of work available.

They are not injecting equity dude. Get it right. It is an asset swap (as you correctly pointed out before this error). No new money is created with QE. Change in equity = 0. (Until interest is paid.) The bank reserves are account entries held at the central bank. They do not "provide liquidity" in a hard sense (esp. when the floor rate is zero, which it could be by a CB committee vote), and since the central bank could just change policy at any time and allow member banks to run an overdraft, which is functionally the same as a loan. Then payments clearing is unimpeded and this whole fake mirage of "reserves" being actual stores of anything useful is vamoosed. (They are a store of information. So useful for accounting fraud detection.)

What is true is that with rate floor hikes the FED were doling out basic income to people who already had money. That interest-income was a stimulus. All to the exact wrong end of town.