A Report from Canada's Library of Parliament Shows What Everyone Gets Wrong About the Economy & Money

The paper is the latest of many that debunk academic theories of monetarism the old-fashioned way: by describing reality.

Long-time readers of this Substack will know how much time I spend moaning, wailing and gnashing my teeth about people getting the economy wrong.

I’m therefore surprised and delighted to share paper, shared by a reader, that accurately describes how the Bank of Canada creates money - and how the rest of the money in the economy is created as well.

It’s refreshing in every way: a model of clear writing and clear thinking based in observing the actual process of money creation as it happens in Canada.

You can see it online here or just download it here

In the 1800s, Samuel Butler had a particular talent for looking at things in different and provocative ways. I used one of his quotes to open my Master’s Thesis “It is said that while God cannot change history, historians can. Perhaps it is for this reason that He tolerates their existence.”

Another provocative idea was when he reversed machine and man as creator and created. He suggested that human beings were essentially the reproductive organs of machinery: that human beings were what machines used to make more machines.

The reason reading this piece may require a similar imaginative leap of understanding is because it means considering the economy from a completely different point of view. Your entire life, you have been a user of money, and this is examining the process from the point of view of creating and destroying money.

The following is the entire text, including the footnotes.

The Introduction reads

Money is created in the Canadian economy in two main ways: through private commercial bank loans or asset purchases, and through the Bank of Canada’s asset purchases. The majority of money in the economy is created by commercial banks when they extend new loans, such as mortgages. However, with the Bank of Canada’s unprecedented asset purchases to reduce the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Canadian economy and to bring inflation back up to target, greater attention has been paid to the Bank of Canada’s money creation and its impact on inflation. An examination of the differences between these two methods shows that money creation through asset purchases by the Bank of Canada is essentially an internal government process, mostly limited by inflation. The examination concludes that external factors, like financial market dysfunction, cannot cause the federal government to run out of money.

(Emphasis mine)

HOW THE BANK OF CANADA CREATES MONEY THROUGH ITS ASSET PURCHASES

“The process by which money is created is so simple that the mind is repelled.”

- John Kenneth Galbraith

1 INTRODUCTION

This paper explores the operational and legal aspects of how the Bank of Canada creates money by buying newly issued federal government bonds and Treasury bills.’ It also discusses how private commercial banks create money.

To soften the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Canadian economy and to bring inflation back up to its target rate, 2 the Bank of Canada recently injected the largest amount of money in its history into the financial system. Through various asset purchase programs, the Bank of Canada has bought federal, provincial and corporate bonds, commercial paper, bankers’ acceptances, Canada Mortgage Bonds, Treasury bills and short-term provincial securities. These asset purchases increased the size of the Bank of Canada’s balance sheet from $120 billion on 11 March 2020 to a peak of $575 billion on 10 March 2021. After winding down some of its asset purchase programs, the Bank of Canada reduced its balance sheet to $478 billion on 12 May 2021.3

Although these measures were taken in the most extraordinary circumstances of a global pandemic, the Bank of Canada also purchases financial assets as part of the regular management of its balance sheet to offset its liabilities, which consist mainly of bank notes in circulation and government deposits. 4

2 THE BANK OF CANADA’S PROCESS FOR CREATING MONEY THROUGH ASSET PURCHASES

The Bank of Canada helps the Government of Canada borrow money by holding auctions throughout the year at which new federal securities (bonds and Treasury bills) are sold to government securities distributors, such as banks, brokers and investment dealers. However, the Bank of Canada itself typically purchases some of the newly issued bonds and a sufficient number of Treasury bills to meet its needs at the time of each auction. These purchases are made on a non-competitive basis, meaning that the Bank of Canada does not compete with the government securities distributors at auctions. Rather, the Bank of Canada is allotted a specific number of securities to buy at each auction.”

In practical terms, when the Bank of Canada purchases government securities at auction, it means that the Bank records the value of the securities, each of which has a unique International Securities Identification Number, as a new asset on its balance sheet. It simultaneously records the proceeds from the sale of the securities as a deposit in the Government of Canada’s account at the Bank - a liability on the Bank’s balance sheet (see Appendix, Table 1).

Since the Bank of Canada is a Crown corporation - wholly owned by the federal government, yet independent of it in the conduct of its monetary policy - the Bank’s purchase of a newly issued security from the federal government can essentially be considered an internal transaction. It records new and equal amounts on the asset and liability sides of its balance sheet, creating money through digital accounting entries?

The federal government can then spend that newly created money in the Canadian economy as it sees fit, subject to Parliament’s approval.

The creation of money by the Bank of Canada through the purchase of assets like Government of Canada securities has fundamentally the same financial impact as the Bank making loans to the federal government, yet the Bank’s governing law, the Bank of Canada Act,’ does not explicitly empower it to make loans of this nature.

Rather, this Act gives the Bank the power to “buy and sell securities issued or guaranteed by Canada or any province” (section 18(c)), as well as the power to

“accept deposits from the Government of Canada and pay interest on those deposits” (section 18(I)). Taken together, these two provisions appear to empower the Bank to create money through the direct purchase of Government of Canada securities at debt auctions.

As the Bank of Canada explains, its purchases of Government of Canada securities are not a way of financing the government’s spending and debt at no cost; the federal government has to repay the securities when they become due. Moreover, the Bank of Canada does not believe that its asset purchases since the beginning of the pandemic will generate high inflation rates, because the Canadian economy is currently facing low inflation. Its decision on when and how to scale back these purchases will be tied to the outlook for inflation.”

3 MONEY CREATION IN THE PRIVATE BANKING SYSTEM

Private commercial banks also create money when they purchase newly issued government securities as primary dealers at auctions. They do so by making digital accounting entries on their own balance sheets: the asset side is augmented to reflect the purchase of new securities, and the liability side is augmented to reflect a new deposit in the federal government’s account with the bank.

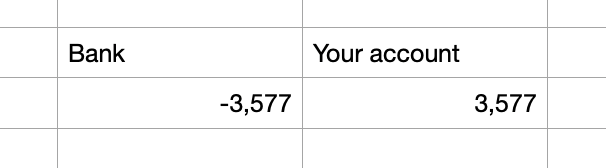

However, it is important to note that the majority of money in the Canadian economy is created within the private banking system every time banks extend new loans like mortgages, consumer loans and business loans. Whenever a bank makes a loan, it simultaneously creates a matching deposit in the borrower’s bank account, thereby creating new money (see Appendix, Table 2).

One key similarity between money creation in the private banking system and money creation by the Bank of Canada is that both are realized by simultaneously increasing the asset and liability sides of a balance sheet.

One notable difference between the two types of money creation is that there is no external limit to the total amount of money the Bank of Canada may create through its asset purchases, other than the impact the additional money created has on inflation. 12 In contrast, the amount of money that a private commercial bank is permitted to create depends on the amount of the bank’s equity relative to its assets.

The limiting rules, known as capital constraints, are established by Canada’s banking regulator in a set of guidelines.13 Another significant difference is that the key factor in a private commercial bank’s decision to give a loan to a private entity is the creditworthiness of the borrower, whereas the key factor in the Bank of Canada’s decision to purchase assets is its ability to achieve its inflation target.

4 CONCLUSION

Both the Bank of Canada and private commercial banks create money by making asset purchases or making loans. However, money creation by the Bank of Canada through purchases of Government of Canada securities is essentially an internal government process; this means that external factors, such as financial market dysfunction, cannot cause the federal government to run out of money.

Inflation is the main limit to the amount of money the Bank of Canada can create through asset purchases.

NOTES

1. In this publication, “money” means bank deposits in Canadian dollars.

The Bank of Canada defines inflation as “a persistent rise in the average level of prices over time.” See Bank of Canada, Understanding inflation, 13 August 2020.

Bank of Canada, “Bank of Canada assets and liabilities: Weekly (formerly B2),” Database, accessed 18 May 2021.

Bank of Canada, Modification to the Operational Details for the Bank of Canada’s Primary Market Purchases of Canada Mortgage Bonds for Balance Sheet Management Purposes, 27 January 2020.

Bank of Canada, Statement of Policy Governing the Acquisition and Management of Financial Assets for the Bank of Canada’s Balance Sheet, 8 April 2021.

Bank of Canada, Modification to the Operational Details for the Bank of Canada’s Primary Market Purchases of Canada Mortgage Bonds for Balance Sheet Management Purposes, 27 January 2020.

Conversely, money is destroyed when the federal government repays its debt to the Bank of Canada.

Government of Canada bonds and Treasury bills are fixed-income instruments that represent loans made by an investor (e.g., the Bank of Canada) to the Government of Canada.

Bank of Canada Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. B-2.

lbid., ss. 181) and 18(). Although these two provisions address loan-making - and both require a loan repayment within a specific and relatively short time frame - it appears that neither provides authority for the type of loans the Bank of Canada makes to the federal government by buying a portion of all new federal government securities and holding these securities until maturity.

Paul Beaudry, Bank of Canada, How quantitative easing works, Speech, 10 December 2020.

Internal government constraints may be placed on the Bank of Canada through laws passed by Parliament that regulate the Government of Canada’s borrowing. Practical constraints, such as inflation, are also a factor. For example, large amounts of new money, if spent in the Canadian economy, could lead to inflation if the aggregate demand for goods and services exceeded the aggregate supply as a result.

In Canada, the banking regulator is the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFl).

Although capital constraints are set out in guidelines rather than in law or regulation, the guidelines are effectively mandatory for banks. See OSFI, Table of Guidelines.Although the federal government cannot run out of Canadian dollars, it could run out of foreign currencies.

All other things being equal, if the Bank of Canada or private banks were to create too many Canadian dollars relative to the size of the Canadian economy, the value of the Canadian dollar could fall against foreign currencies.

To start, I want to emphasize that the description above of money creation in the Canadian economy is a based on observation and a straightforward, step-by-step factual description of the operations.

In other words, this is not a matter of opinion or theory. This is how it actually happens, and it is not a matter of debate, because it is a matter of fact.

So if an economist says that the description is theoretically incorrect, that’s a problem for their theory, not for these facts.

This is the way that money actually gets created, and the reason it is baffling or “repels the mind” as Galbraith has it, is explained, is because it represents a completely different paradigm for understanding money creation from the one we have been taught for many years.

When you talk about the difference between paradigms, it is not just a tweak in an existing system. It is a very different way of interpreting the world that is not compatible with current explanations. Classic examples from science include the shift between believing the earth was at the centre of the universe with the sun, planets and stars revolving around us, to the discoveries that led us to understand that the earth goes around the sun, or the shift from Newton’s physics to Einstein’s.

In all these cases, it fundamentally changes the way we understand the interactions between elements. The Copernican Revolution changed our understanding of something as simple and familiar as night and day. Sunrises and sunsets are the earth spinning, not the sun revolving. It is often a complete recentring of perspective.

That’s what we are dealing with here.

It can be explained in part by a long-running debate between two schools about money - the “metallists” and the “chartalists,” dating back centuries, as explained in this paper here:

“During the 16th and 17th centuries, the ‘Metallists’ and the ‘Anti-Metallists’ or ‘Chartalists’ paved the way for successive debates between various schools of thought for centuries to come…

For the Metallists, money, though it may come to serve other functions, originated as a medium of exchange. Exchange, it is argued, was initially conducted on the basis of barter, with individuals trucking their goods to the local trading venue and attempting to exchange what they brought for what they wanted. Thus, barter exchange required the famous ‘double coincidence of wants’ so that two-party exchange could only occur if each of two individuals wished to exchange that which they possessed for that which was offered by another… The Metallists maintained that society settled on a metallic currency (gold, silver, etc.) so that the money would have (intrinsic) value. They believed that money’s ability to fulfill the medium of exchange function depended “on its being a commodity with an exchange value independent of its form as currency”

This is the dominant idea of mainstream, “monetarist” economics - and in both Mettalism and Monetarism, money doesn’t matter, because it is seen as neutral.

Chartalism, on the other hand, see “recognize the power of the State to demand that certain payments be made to it and to determine the medium in which these payments must be made.”

I will say two things which I hope will simplify all of this, by asking people to consider the following concepts about the state and money.

I use the word “obligation” because there are many degrees of it, from total to none.

Money is a legal record of obligation.

All communities of are based on mutual obligation.

The purpose and reason for the state is to regulate our obligations to one another

It’s possible to create new obligations.

For obligations to be effective, they must be enforced

People can be held to those obligations

People can be released from these obligations.

When systems of obligation fail, people use other means to get what they want

So, obligations can be as serious as you can get. It covers the entire range of possible obligations across human behaviour, including the ones that define every aspect of our social identity. Constitutional rights, sacred religious beliefs, criminal, civil and contract law, human rights law, morality, political ideologies.

These are all social and cultural social systems and belief systems that are defined by the frameworks of obligations to one another, including every single aspect of collective identity. It is morally neutral in that obligation is nothing more than a social lever to have another do what you desire.

Obligation is the basis for all authority, and all structure, whether it is just or unjust, destructive or productive. You can be obliged to, and you can be obliged not to.

In all economic and financial relationships, these obligations are supposed to be expressly stated and recorded as a legal transaction. Whether those obligations will be enforced depends on the legal context in which they exist, and whether courts will enforce them.

That’s what money is. It is a token of obligation, expressed in numerical form.

The ease with which money is created, by the stroke of a pen, or by sending an e-mail, is because we think of money as a “thing,” and because we don’t see how something so serious could be created so easily.

The idea that something is “mere information” or philosophers dismissing writing or math as “little black marks on a page,” fail to understand meaning and value at all. Of course mere information can mean nothing. Meaning is about how important something is. Information can mean nothing, or it can mean everything.

People think, well, it’s just information, it can’t matter, when everything that matters is information. If it matters, it is information. It has to be information to matter.

If it all seems awfully dangerous, it is because it is. Creating money willy-nilly and shooting at it at people like a T-shirt cannon at a football game can be chaotic and destructive.

However, the fact that this is how it is running, and people are making policy based on models that do not reflect what is happening.

It is not theoretical, nor hypothetical, nor is it an analogy. It does not borrow mathematical formulas from physics.

The Government of Canada is selling bonds. Some are always set aside for the Bank of Canada to buy. So, the Bank of Canada buys the bonds and gives the Government of Canada the money.

What is happening is actually exactly what is described by some other economic schools of thought, including Post-Keynesians and Modern Monetary Theorists.

The Government of Canada and the Bank of Canada create the money by spending it into existence. This happens fresh, each year, in every budget.

The Bank of Canada creates the money for the Government of Canada to spend, and when the Government of Canada pays the money back to the Bank of Canada, it does not go into the coffers at the Bank of Canada. It is destroyed.

The Bank of Canada is a Crown Corporation. (For non-Canadians, that’s what we Canadians call corporations that are owned by the government, because we are part of the Commonwealth and our head of state is King Charles).

It’s owned by the Government of Canada, therefore the creation of fiat money by government is essentially an internal transaction. It is not possible for the Government of Canada to go bankrupt in a currency, which, according to the constitution, it has a monopoly on creating.

Of course this can seem disorienting, because it is alien to our experience to the economy, as users of government fiat money, which includes everyone other than the Canadian Government.

However, what that means is that the total Federal Budget is the amount of all the fiat money being created in a given year, and that is the government’s contribution to the economy.

One of the common objections to trying to explain this process is that people, including many very serious economists, will say that MMT is advocating that governments print money to support spending or deficits.

What the evidence shows is that all the money is being created anew, and that the federal government is spending money into existence, because that’s what each year’s budget does. It supports the enforcement of obligations.

The current orthodoxy of metallist/monetarists is operating based on the (admittedly, very reasonable) belief that one year’s budget is paid for by last year’s taxes. Of course it’s a reasonable belief, because the notion that money is being created by government each year and that taxes are destroyed seems completely insane, so long as you think of money as physical item.

But money is not a physical item. It is a symbol of a social obligation, and both symbols and obligations can be created and erased. In the actual economy, and in legal, political and accounting reality, that obligation is recorded in the two sides of double-entry bookkeeping.

It’s important to note, this is not because of the invention of computers. All money is an accounting entry. It always has been. Money is a kind of information. It’s a symbol, and as a symbol, money is typed into existence, and deleted out of existence in computer databases, which are the modern version of the clay tablet.

In the UK, “tally sticks” with marks on them were split down the middle and were used as money, and to pay taxes, where they would be burned. In 1834, burning the tally sticks burned down the British Houses of Parliament.

Private Money Creation through the Creation of Credit Money

While only the Canadian Government and the Bank of Canada can create actual, real, Canadian dollars, anyone and everyone can create an obligation. That’s what an IOU is. If you write an IOU to get someone to lend you $50, you have created an obligation to pay back $50 that didn’t exist before.

The paper makes a supremely important and simple distinction here, pointing out that while the Bank of Canada and the Government of Canada create new money in the act of spending, it is not the only entity putting money into the economy.

Most of the money being created in the economy is when commercial banks extend a loan. Most of those are mortgages.

And in what is perhaps the craziest aspect of this, what is actually happening when you take out a mortgage, is not that the bank is lending you money that someone else has stashed with them for safekeeping.

If you are the one taking out the mortgage, you are the one creating the money you are going to have to pay back with interest. A mortgage is a promissory note. It is an IOU.

The scene from “It’s a wonderful life” - the one where a kind and noble moneylender is both the victim and hero of a Christmas classic. There’s a panic, and the townsfolk crash Savings and Loan trying to take out all their savings, demanding where their money is. Jimmy Stewart pleads with them, saying:

“The money’s not here. Your money’s in Joe’s house...right next to yours. And in the Kennedy house, and Mrs. Macklin’s house, and a hundred others. Why, you’re lending them the money to build, and then, they’re going to pay it back to you as best they can. Now what are you going to do? Foreclose on them?...Now wait...now listen...now listen to me. I beg of you not to do this thing.

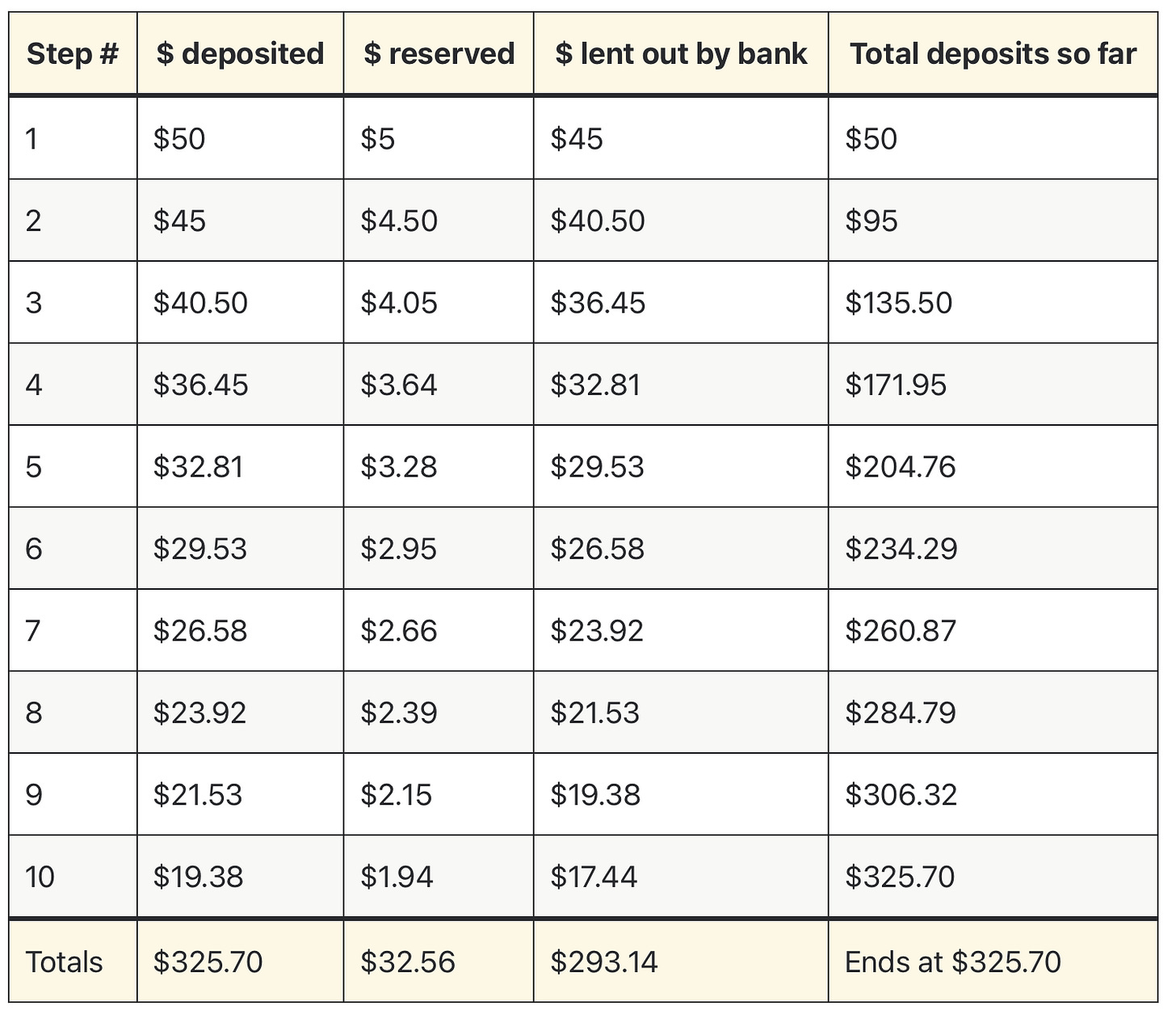

Here is a chart of the money multiplier. The idea is that someone deposits $50, the bank lends out 90% of it, which is deposited in another account, where 90% is loaned out.

Belief in the money multiplier under the Obama administration was used to explain why banks were getting a bailout, not people.

This 2010 Federal Reserve paper argues, based on empirical observation, that the Money Multiplier does not exist, and notes that the post-1970’s economists who are monetarists - including “New Keynesians” like Paul Krugman - don’t include money in their analysis, “the institutional structure in the United States and empirical evidence based on data since 1990 both strongly suggest that the transmission mechanism does not work through the standard money multiplier model”

The money multiplier story suggests that banks increase the money supply in the following way. When a bank makes a loan, the borrower will deposit it another bank. That bank will keep some of the money, and lend out the rest, which will be deposited into another bank, which will do the same.

In fact, the process is much simpler, although weirder.

When it comes to private lending, as the paper says, banks create money in the act of lending. They are extending credit. The money is not being taken out of reserves or other people’s deposits. It’s pure credit, denominated in the currency of choice. The calculations of how much credit to extend depend on regulations, interest rates and reserve requirements.

Having qualified, the borrower signs the mortgage, which is a promissory note that binds them to years of mandatory payments, where failure to keep up with the payments could result in the loss of housing.

Someone at the bank then types in the amount of the money being extended to them into the customer’s account. The double entry bookkeeping is as simple as it gets - one number is the negative of the other.

And, as you repay your debt, it goes down. The debt you owe is your liability, and the bank’s asset. So as you pay it down, the obligation (money) is being cancelled.

How the hell can anyone make money extending credit and then destroying money when it is repaid?

Banks are not lending from their reserves, nor do they use people’s savings. All that stays with the bank.

The banks are creating new money by extending credit with the mortgage. It’s not someone else’s money that you’re getting to buy your house. It’s newly created credit money, that can be cancelled.

Accrued interest costs are routinely more than double the amount of the credit that was advanced in the first place.

The loan is secured against real property, so if there is a default, the creditor can seize it and sell it.

While it may be challenging to wrap our minds around the idea of money being created and deleted, this exact process has been described by other central banks as being the means by which the system functions. The fact that money is created in this fashion has been recognized by the only people who are actually legally allowed to create currency: central banks.

This is the factual explanation for how it happens. It’s actually much more straightforward of an operation than the Rube Goldberg money multiplier.

A person signs a guarantee that they will be a reliable source of income for years or decades

The bank extends credit in that amount, secured against a piece of real property.

The mortgage, not the property, is the borrower’s liability and the bank’s asset, which it may sell to investment banks to bundled up and sold.

Because they are denominated in dollars, we think of all the money being the same, but there is a colossal difference between government created fiat money and private credit money in the economy.

There’s a saying that there are only two certainties in life - death and taxes. This misses a third certainty, which is that a national government can always create money in its own currency to pay bills.

Most money in the economy is privately created credit money, not government created spending. Over 90% of the money in the economy is privately created credit money, mostly created by banks in the act of extending credit to create mortgages.

Government, by law, has the monopoly on creating currency. That means bills and coins. It is a guarantee that you can turn these fiat dollars into cash. It’s not interest bearing. That makes it intrinsically more certain.

In stark contrast. Privately extended credit has interest applied to it, which means that unlike equity or cash, or fiat money, it has the continual force of interest which by nature, and design, extracts far more money from the borrower than they received in the first place.

The private sector is less certain and more risky. This explains its “dynamism” because higher risks mean higher rewards - but not for everyone. Winnings are concentrated among a few while distributing the losses among the many.

The collapse and break in payments is not because governments cannot pay their bills. They can. It is because individual mortgage holders can no longer service continually growing debt, because the money to service it is not there.

This is why private debt is what causes financial collapse; it is why financial collapses lead to social unrest, and it is why, whenever there is a crisis, governments and central banks interventions just keep making the problem worse.

Obama used the money multiplier to justify bank bailouts, because he had been persuaded that the government giving money to banks would allow the banks to expand lending. The same justification and model have been used again and again, including in Canada during the pandemic.

“Credit and liquidity support through financial Crown corporations, Bank of Canada, OSFI, CMHC and commercial lenders (e.g., Domestic Stability Buffer, Insured Mortgage Purchase Program, Banker’s Acceptance Purchase Facility)” was “In the range of $500 billion”

In addition,

“the government will purchase up to $50 billion of insured mortgage pools through CMHC. This action will provide stable funding to banks and mortgage lenders in order to ensure continued lending to Canadian consumers and businesses.”

I will emphasize that last line: “In order to ensure continued lending to Canadian consumers and businesses,” which explains why these emergency measures keep making the problem worse, because every time we have a crisis where Canadians can no longer service their private debt to commercial banks, the Government of Canada, the Bank of Canada and CMHC provide lenders with hundreds of billions of dollars more so that consumers and businesses can go further into debt - which they did. So did people around the world, creating one of the largest global and asset bubbles in history, which is currently collapsing.

The facts and the observations may be challenging, but they are not in dispute.

The belief in monetarist / metallist fallacies is the reason our social, economic and political crises keep getting worse - including the current disaster that is the U.S. budget shutdown.

-30-

Can you clarify how the "bank bailouts" work in the context of the capital asset ratios banks are required to maintain?

I'd assumed that without the government taking the (toxic) mortgages off the banks hands the banks would have been forced (eventually) to mark those assets to a now much reduced market value or even to write them off. These markdown or write offs would have had to be carried down to the banks balance sheet, which would have thus in turn impacted their capital ratios and thus their ability to loan.

So, it's not unfair to say that that without intervention, loans would have dried up?

It's fair to argue that there were other ways to skin the cat, however.

The government could have just given the money to consumers to pay their mortgages off, or they could have just changed the capital ratio requirements to give the bank more headroom, although I have no idea if they represent more or less systemic risk.

Or am I getting this all wrong?

This is a fine summary of the case made by MMT to explain how the economy works on a factual basis.

It leads to other very important questions:

1. How should government determine how to spend money into existence/what should it fund?

2. What then is the role of taxes in the economy if taxes do not in fact fund government spending, and

3. What is the government’s role in ensuring equitable outcomes for citizens in the economy?

Each of these questions lead to book-length conversations.

As a starter, government budgets are about choices, and shape the “deal” citizens have with the government. Taxes destroy money but are selectively applied to constrain spending and shape spending decisions by citizens and corporations.

But that third question… aye that is the one that really is the most significant one. I would say we are long past the time where government needs to strike a new “new deal” with citizens!