Are You Better Off than You Were 40 years ago?

Three reasons for growing inequality, and the risk of mixing markets

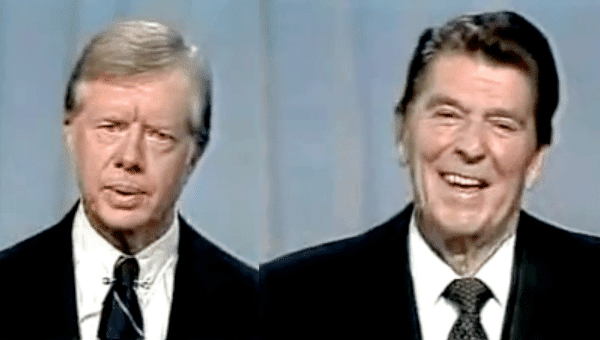

In the 1980 U.S. Presidential debate, it’s been suggested that it turned on a critical question - when Ronald Reagan asked voters “Are you better off that you were four years ago?”

40 years later, we can ask the same question, and for a surprising number of people, the answer is that no - because their incomes stopped getting better around that time.

As you can see from this chart, in the mid-1970s’ there was a change in the economies of the U.S., UK, Canada, Ireland and Australia - English-speaking countries - that saw the highest earners - the top 1% - start to take home more and more of total income, starting in the years 1976-1978. This pattern did not occur to the same degree in continental Europe and Japan.

In 2013, at the height of an oil boom in Alberta, an economist working for the City of Edmonton said that, adjusted for inflation, 99% of the residents of that city had seen no increase in their wages in 30 years.

And that same year, Economist Miles Corak wrote that “The typical [Canadian] household is now no better off, indeed about $3,000 worse off, than it was in the mid to late 1970s, in spite of 35 years of economic growth.”

So what happened in the 1970s? There is no single reason for growing inequality since the 1970s and early 1980s - there are many. The usual culprits are digital technology, globalization, taxes and a lack of competitiveness. But is there something that else driving those changes - and that inequality? The answer is yes - because in the 1970s there was a wholesale change in the way that corporations, governments and central banks, all operate.

1. Corporate Culture: from Stakeholder Capitalism to Shareholder Value

After WWII, there was growing anxiety over the class of “professional managers” who were running established companies. In 1976, two finance professors, Michael Jensen and Dean William Meckling published a a paper called “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behaviour, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure.”

“The article first defined the principal-agent problem and created agency theory. In the authors’ construct, shareholders are the principals of the firm — i.e., they own it and benefit from its prosperity. Executives are agents who are hired by the principals to work on their behalf... Jensen and Meckling argues that when executives squander firm resources to feather their own nests, the result is both bad for shareholders and wasteful for the economy. Instead, the theory goes, the singular goal of a company should be to maximize the return to shareholders.”

This is one of those ideas that is pure ideology. It is very clearly a kind of moral judgment about who deserves the money, not an analysis of how value is created or what the best or most productive use of the money for the future sake of the firm would be.

It’s not hard to see a basic flaw in the argument, with the real-world example of the saw the stock market works.

There is an idea that investing in a company provides the firm with money to help it make improvements - buy new equipment — but that is only true if it is venture capital or a new issue of shares. Most investments are “brownfield” investments in established companies that may have been around for decades. Shareholders’ intentions may be purely speculative: they are looking to buy low and sell high, but they may even sell their shares at a loss and get out.

Because not everyone is an initial investor, not every investor contributed to the actual capital investment in the firm or took the same risk. Unless you are buying shares being issued directly by the firm, the firm isn’t benefiting directly from all the investor’s stake. So why should all benefits go to someone who is a speculator, not an investor ?

None of that stemmed the popularity of the idea of shareholder value from spreading. The question was how to make actually set up an incentive that would get the people who ran the company to increase the stock’s value?

One solution was to link executive compensation with the company’s stock price. In 1981, GE CEO Jack Welch helped popularize the term, “shareholder value,” as the strategy to follow, although its roots can be traced back to a blistering polemic by Milton Friedman in the New York Times in 1970.

The idea behind shareholder value was that the CEO was a mere employee of the real owners of the business, the shareholder, and share price became the singular focus of boards, CEOs and companies. Actual performance — profits and losses — became less important than meeting the Wall Street analyst’s expectations of what the share price would be.

In practice, shareholder was a used as a rationale to squeeze all stakeholders and extract maximum profit. Ha-Joon Chang writes that, “Distributed profits as a share of total US corporate profit stood at 35-45 per cent between the 1950s and 1970s, but it has been on an upward trend since the late 1970s and now stands at around 60%”

Chang adds “Jobs were ruthlessly cut, many workers were fired and re-hired and non-unionized labour with lower wages and fewer benefits, and wage increases were suppressed (often by relocating to or outsourcing from low-wage countries such as China and India — or the threat to do so.)” Some companies outsourced work with the precise goal of “boosting” the stock price.

One of the companies that pursued this strategy was GM, once the dominant carmaker on the planet, which ruthlessly cut back, built shoddy products, lost market share and finally went bankrupt in 2009 and required a government bailout. It’s worth saying, however, that it was GM’s financial arm that went bankrupt, because of the global financial crisis. When people talk about “financialization” and you don’t know what it means, think about it this way: after “financialization” General Motors was not a car company with a loan division: it was a finance company that made cars.

These reasons - among others - may be why Jack Welch himself said that “maximizing shareholder value was the dumbest idea in the world.”

Shareholder value has been a driving force behind growing inequality and increased concentration of wealth among executives and shareholders at the expense of workers. To many capitalists and free marketers, that is the point. But there is a major problem with the single-minded pursuit of shareholder value: shareholders themselves, unlike employees, management and the community where the company is located, may have no interest in the long-term viability of a company, especially if they are short-term speculators.

Roger L. Martin, Dean of the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto has written an entire book on the subject of shareholder value, called Fixing the Game. He gives the example of a problem for companies and investors alike: a stock that was initially offered and sold to the public at $20 is sold, and re-sold, eventually rising to $100. The company only got $20 from selling its share to the first investor, but the investor who buys it at $100 is going to expect it to perform much better.

Writes Martin:

“The company needs to earn 15 percent on $100 per share of expectations capital, even though it only has $20 of real capital with which to do it. Rather than a 15 percent return on its real equity (or $3/share) it has to earn a 75 percent return on its real equity (or $15/share), a deeply challenging task and one that even the best companies are unlikely to achieve over time.”

Pursuit of profit through “shareholder value” alone undermines the company by increasing the long-term risk for the company, its employees, and the broader economy. Jurisdictions in Europe and elsewhere have sought to “reduce the influence of free-floating shareholders and maintain (or even create) a group of long-term stakeholders (including shareholders) through various formal and informal means.”

Despite all that, it still seems hard to argue against maximizing shareholder value or profit. Isn’t maximizing profit the whole point? It is generally accepted that it is.

There is a simple argument for why shareholders shouldn’t take all the benefits. As Gaël Giraud put it, “Ownership implies full liability... Full liability was actually the implicit assumption of Friedman (1953) when he claimed that, in the long-run, markets are efficient.”

Shareholders are not taking all the risks: in fact, they are specifically shielded from risk in the event that a company fails. They may lose their investment, it’s true, but shareholders are not liable for the failed company’s debts or losses. Employees may lose their jobs, future earnings, pensions, and benefits, and company directors may be personally liable for losses. Shareholders are not.

The question arises: if shareholders are exempt from the full consequences of taking a risk, why should they enjoy the full benefit of the reward? The current liability structure effectively creates a one-way valve for the flow of corporate benefits.

That is why it it is entirely justified to reduce the return on shares in order to better reflect the risks being taken by all stakeholders, including labour.

What’s more — as has happened again and again in recent years — the risk of the failures of investment banks, banks, and private businesses has been borne by governments and citizens, through government bailouts, loans, and various kinds of support. (To say “taxpayers” is limiting since the resulting financial disasters have resulted not just in astronomical payouts and bailouts to private companies, but the economic fallout of the downturn has often resulted in massive cuts to public services — health, education, infrastructure, policing, social assistance or food stamps.)

If citizens are expected to the absorb the risks and pay off losses incurred in private deals taken by corporations and banks, citizens should be able to reduce their own risk (through government regulation) or get benefits in return: taxes, a share in profits, or a say in the company is to be run.

Another mistaken assumption with shareholder value may have been that it would be based on dividends - on the profits that the company earned and distributed to shareholders. Instead, it became focused on the share price in the stock market, which could be manipulated by a variety of other means - from using profits to buy back shares and inflate the price of a sagging stock, or accounting manipulations. Buybacks in the S & P 500 have reached 95% of profits.

The reason why shareholder value became so toxic is that instead of focusing on real-world results — actual sales and profits — CEOs were required to focus on share price. Roger L. Martin compared the negative results of shareholder value to gambling in sports, where a coach and team are playing the game to ensure a win for gamblers instead of for themselves or the fans. What’s more, he compared it to teams and coaches gambling on the games they were playing in. Shareholder value changed the incentives for the people running companies — instead of long term stability and profit, it changes into a game of fulfilling the expectations of speculators, which may be totally unrealistic.

In gambling on sports like American football and basketball, people don’t just bet on whether teams will win, but how many points they will win by. If coaches or players on the team are gambling on the outcome of games they are playing in, they could be throwing games, missing points to meet the target set by gamblers to get a big payday.

This is the actual situation many CEOs and managers face, since their stock price (and compensation in stock options) depends on meeting the expectations of the market.

Writes Martin, “What would lead [a CEO], to do the hard, long-term work of substantially improving real-market performance when she can choose to work on simply raising expectations instead? Even if she has a performance bonus tied to real-market metrics, the size of that bonus now typically pales in comparison with the size of her stock-based incentives. Expectations are where the money is. And of course, improving real-market performance is the hardest and slowest way to increase expectations from the existing level.”

It is worth noting that this is true of the publicly owned and traded companies, but not privately owned ones. Privately owned companies can continue to operate in the “real world” at least in the sense that they are not governed by the quarter-to-quarter earnings and expectations of the market.

What kind of “point shaving” and “game throwing” activities do CEO’s engage in? One is using profits for share buybacks, to keep the price of their own stock inflated. This is a gift to existing shareholders, who can sell at an inflated price, but it also means that executives and managers can exercise their stock options and hand themselves vast bonuses. Ha-Joon Chang writes:

“Share buybacks used to be less than 5 per cent of UD corporate profits for decades until the early 1980s, but have kept rising since then and reached an epic proportion of 90 per cent in 2007 and an absurd 280 percent in 2008. William Lazonick, the American business economist, estimates that, had GM not spent the $20.4 billion that it did in share buybacks between 1986 and 2002 and put it in the bank (with a 2.5 per cent after tax annual return) it would have had no problem finding the $35 billion that it needed to stave off bankruptcy in 2009.”

Let’s return briefly to the notion of generating profits as a surplus that lowers risk. Profits, surplus and savings generated by work are lower risk in a way that investment is not. Using your own hard-earned profits to buy shares in your own company is trading a secure surplus for a risky one.

Globalization — which has been blamed for growing inequality in the U.S. and Canada — has been driven in part by the pursuit of shareholder value. Companies that could be profitable operating entirely in the the U.S., Canada or elsewhere outsource work in order to “goose” profits and their stock price.

What’s more, it has not delivered on growth.

“We imposed a whole new set of rules to mitigate those agency costs and increase the return to shareholders. Yet, it simply hasn’t worked out. Total returns on the S & P 500 for the period from the end of the Great Depression (1933) to the end of 1976, the beginning of the shareholder-value era, were 7.5% (compound annual). From 1977 to the end of 2012, they were 6.5 percent — suggesting that shareholders have little to celebrate, despite having been made the clear priority.”

Shareholder Value: The Expectations Market vs. the Real World

This distinction between actually creating value and just trading it around is how Roger L. Martin separates the “real economy” and the “expectations economy” in his book “Fixing the Game.”

He uses the analogy of sports — and what the National Football League actually did to clean itself up — as an example. In the context of sports, the real economy is when coaches and teams focus on winning games: that is all they are supposed to do, and the league focuses on creating the best possible experience for customers and fans, through a whole series of measures. The “real economy” can continually grow — you can get new fans and new sources of revenue, and the proceeds and benefits are distributed widely. The players and coach on the losing team still get paid, because they made a contribution and worked for it.

The “expectations economy” is gambling on the outcome of the game. Gamblers don’t just bet on who will win or lose, they bet on how much a team will win by — “the spread.” It is a zero-sum game: for one person to win $5, someone else has to lose $5.

As Martin argues, there are two problems for American Capitalism. One is when you mix the real economy and the expectations economy together — if players and coaches are betting on the games they are playing in, and are deliberately throwing games to win bets.

The other is when the expectations game takes over, because while real-world results are, of course, constrained by what happens in the real world, expectations aren’t: they can be, and are, wildly unrealistic — both positive and negative.

“The real market is the world in which factories are built, products are designed and produced, real products and services are bought and sold, revenues are earned, expenses are paid, and real dollars of profit show up on the bottom line. That is the world that executives control — at least to some extent.

The expectations market is the world in which shares in companies are traded between investors — in other words, the stock market. In this market, investors assess the real market activities of a company today and, on the basis of that assessment, form expectations as to how the company is likely to perform in the future. The consensus view of all investors and potential investors as to expectations of future performance shapes the stock price of the company.”

Martin’s thesis is that the “real economy” focuses on customers and by building something of value, profits ensue. The “expectations economy” is focused on shareholders and performance of the stock.

The issue of “mixing markets” is a dangerous one that is usually completely overlooked, because the higher returns being delivered in the short term lead to higher risks in the long-term.

Without intending to, this theory has forced CEOs and other executives of publicly traded companies into the position of being coaches whose compensation is based on gambling on the outcome of their games. Depending on who they are playing, a coach might have an incentive to bet against himself, and then guarantee a loss.

The focus on shareholder value and executive compensation tied to stock performance has had a number of serious effects. One of the ways to keep increasing stock performance is to hollow out your company, continually squeezing stakeholders and workers until your company collapses (as with GM), or to raise prices at the expense of market share.

Another is that the focus shifts from trying to manipulate the expectations of the market through accounting tricks and deception: shifting earnings or spending into different quarters to meet expectations, conceal liabilities, or even drive down expectations in one quarter to meet expectations for the next one. These are all short-term strategies that put the company at risk.

“The accounting scams of 2001 — 2002 as practiced by Enron, WorldCom, Tyco International, Global Crossing and Adelphia amounted to the biggest business scandal in at least a generation.”

As Martin says, “The accounting scams of 2001 — 2002 as practiced by Enron, WorldCom, Tyco International, Global Crossing and Adelphia amounted to the biggest business scandal in at least a generation.”

In the “real economy,” money is distributed throughout the system as part of the process of generating value. Everyone who works at a company contributes in some way to the products or services it makes, and, to use the old marketing saw “nothing happens until a sale is made.” The company depends on the customer handing money over for the product or services. The customers get what they want, and the company makes money.

In the expectations economy, even real growth and real returns can become irrelevant. The fact that “Wall Street” and “Main Street” have come uncoupled should make this clear. Markets and unemployment - even markets and economy - are disconnected. This is in part because companies have continued to keep their stocks up through stock buybacks, which have been enabled by “easy money” and decades of low interest rates.

Another example of disconnect Martin pointed to was Microsoft. Over a last decade it nearly tripled its revenue and profit, but consistently traded in a narrow range between $25 and $30. He also points out that market makers or specialists are:

“consistently among the most profitable businesses in America, earning supernormal returns year after year, even when the markets plummet and the rest of us lose ... hedge fund managers James Simons and John Paulson each made over $2 billion in personal compensation in 2008 while markets were plummeting.”

Martin writes that, “Our theories of shareholder value maximization and stock-based compensation have the ability to destroy our economy and rot out the core of American capitalism.”

He goes on to write,

“...since [executives] spend most of their time trading value around rather than building it, they lose perspective on how to contribute to society through their work. Customers become marks to be exploited, employees become disposable cogs, and relationships become only the means to the end of winning a zero-sum game.”

Just as a reminder, Martin not a spokesperson for Occupy Wall Street: he is the Dean of the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto. His book was published by the Harvard Business Review Press, and blurbed by Paul Volcker, former chairman of the Federal Reserve under Ronald Reagan.

The “zero-sum” game nature of the expectations market — of trading — is that a hedge fund manager’s gain is literally someone else’s loss. One example is by “buying short” which means you get paid if the a particular investment drops in price instead of going up. One of way of looking at that short selling is as a kind of insurance against risk (as hedge funds and short buyers will argue).

Short buyers and hedge funds don’t operate like regular insurance companies (to say the least). Insurance companies do what they can to mitigate their own risk and that of the people they are insuring through inspections, interviews, and so on. Hedge funds and short sellers can, and have set out to deliberately distort the market — to make it more volatile or to drive prices down so they can collect on their short bet.

A now-famous example was described in Michael Lewis’ The Big Short, where Mike Burry, a neurologist-turned-investor who was trying to pick stocks he could bet against.

“[Burry] set out to cherry pick the absolute worst ones, and was a bit worried that the investment banks would catch on to just how much he knew about specific mortgage bonds and adjust their prices.

Once again they shocked and delighted him: Goldman Sachs e-mailed him a great long list of crappy mortgage bonds to choose from. “This was shocking to me, actually,” he says. “They were all priced according to the lowest rating from one of the big three ratings agencies.” He could pick from the list without alerting them to the depth of his knowledge. It was as if you could buy flood insurance on the house in the valley for the same price as flood insurance on the house on the mountaintop.”

The credit default swap was a zero-sum game. If Mike Burry made $100-million when the subprime mortgage bonds he had handpicked defaulted, someone else must have lost $100-million. Goldman Sachs made it clear the ultimate seller wasn’t Goldman Sachs. Goldman Sachs was simply standing between insurance buyer and insurance seller and taking a cut... Burry’s bet paid off: by the end of 2007, “ in a portfolio of less than $550-million, he would have realized profits of more than $720-million.”

The techniques of “shareholder value” appear to work together to make investment less risky, and work more so. And the people who have been running central banks since the early 1980s have been doing the same.

Inflation fighting = job fighting?

For 90% of the people in Canada, the U.S. and the UK, wages have been stagnant for 30+ years. There has been economic growth, but it has accrued almost entirely to the top 10% (and even more so to the top 1%). Where once being a millionaire was the sign of great wealth, now it is being a billionaire — a thousandfold increase.

The role of central banks until the energy and inflation crisis of the 1970s had been to smooth out the business cycle: governments and central banks would run a deficit and spend to stimulate the economy in a recession, and then in good times they could apply money to the debt and change interest rates to keep the economy from overheating.

That changed with monetarist / neoconservative / neoliberals ideas taking over government and central bank policy. Instead of smoothing out the business cycle, conservative politicians insisted that governments should always “live within their means” and never run a deficit under any circumstance. Inflation fighting was the major priority - it became the sole mandate of central bank monetary policy - in some countries, by law.

Monetarists like Milton Friedman (and Margaret Thatcher) argued that government inefficiencies stifled innovation, that taxation was paternalistic and that individuals knew better how to spend their money than the government did, and that too much regulation, high taxes and public debt were causing inflation, which threatened economic growth.

These, along with privatization and tax cuts was part of a broader effort to “reduce the size of government” that would spur growth in the private sector. There has been economic growth: but it has all been confined to the best-off 10%. Neoliberalism has certainly not delivered on its promise of greater prosperity for all.

Part of the reason is that a singular focus on fighting inflation values investment over wages. As Joseph Stiglitz wrote in The Price of Inequality, in 1993 the Federal Reserve actually intervened in the economy to prevent unemployment from getting too low, because it risked getting to a point that wages might rise, driving up inflation.

Some years ago, in Canada’s Financial Post, Statistics Canada’s former chief economist, Phillip Cross, urged the Bank of Canada to consider raising interest rates, and governments not to stimulate the economy, because Canada’s unemployment, at between 5% and 7% is getting “dangerously low.” The major danger was that the economy was getting so hot people might start asking for raises, or businesses might have to start giving them in order to attract employees.

Currently, there are projections that unemployment could rise in Canada by over 200,000 in the next few months, and the government of Canada and most provincial governments are engaged in mixed austerity and large deficits.

There policies are usually being advocated by conservative, pro-business free marketeers. But how is this the free market? It is literally a central bank intervention to make sure that central banks are protecting risky investments and ensuring that wages are low. One of the way wages are kept low is through excessively high unemployment. Other “inflation-fighting” measures are low-cost imports (free trade and globalization), and yet another is from foreign temporary workers (not immigrants).

A quick point here about “free markets”: in the 19th century, when activists and political thinkers were talking about the “free market,” they wanted to be free from paying rent to private aristocrats and landlords who were born owning their property, and could demand their payment and really provide little or nothing in return. That was the dominant economic and political system in Europe at the time - feudalism.

The “free market” was not about being free from taxation in exchange for infrastructure or public services, or democratically elected governments we have today that provide value for taxes in the form of infrastructure and public services.

So the “free market” was about “freeing” the market from the overhead of paying money to aristocrats, or “rentiers.”

Some kinds of inflation are a feature, not a bug

Monetarists think inflation is “too much money chasing too few goods” and that is a bad thing. The problem with the inflation caused by the oil crisis in the 1970s is that it was imposed by a cartel and prices couldn’t be negotiated. The oil crisis was caused by an artificial shortage: it wasn’t that there was too much money chasing too little oil. It’s that there wasn’t enough money to pay for the oil that was needed.

But there is another kind of inflation: inflation from the bottom up, from wage increases and raises. If employees see that prices in the economy are rising (or that a company’s profits are soaring because due to their own work) they may ask for a wage increase, which will increase prices of the products and services they produce. Or, if there is a shortage of a specific supply employers will have to offer wage increases or benefits to attract and keep applicants. You then get an inflationary spiral that is actually part of economic growth and full employment and increased production.

In fact, China’s highest level of GDP growth — over 25% a year — was in the early’s 90s, when its inflation rate reached near 25% .

As Ellen Ruppel Shell wrote in Cheap, that’s when Chinese wages started to stagnate.

The effect of Canadian anti-inflation policies can be seen in this graph, where inflation flattens out starting in 1984.

Chart – historic CPI inflation Canada (yearly basis) – full term

By trying to fight inflation, monetarism actually interferes with the free market by letting employers dictate the price of labour: it is price fixing, and it in the long term actually impedes growth.

What’s more, keeping inflation low actually makes debt — which is easy to take on at low interest rates — harder to pay off, both for individuals and for governments.

The explosion in public debt in the late 1970s was due in part to inflation caused by the the energy crisis, but the growth in debt that followed was partly a result of monetarist anti-inflationary policies. Investors consider inflation on government bonds a “tax” that is a concealed confiscation of wealth. This seems to be a double standard for public and private investments. The same would also be true of inflation with private bonds: they speculated and they lost. (What’s more, capital losses on a private investment can be used to reduce the tax paid on capital gains.)

For many of the economists who make these policy decisions, the fact that 90% of the population has seen no wage growth in 30 years is not just irrelevant: it isn’t even measured. GDP measures overall economic activity, not distribution, so as long as the rich keep getting richer, it will be treated as a benefit for all.

So just to repeat: for more than 30 years, it has been the policy of central banks to keep inflation low by keeping wages low and unemployment high, on the premise that inflation stifles growth. And yet, as wages stagnated for decades, no (or few) economists could explain what was wrong.

Stiglitz writes

“A focus on inflation puts the bondholders interests at centre stage. Imagine different monetary policy might have been is the focus had been on keeping unemployment below 5% rather than on keeping the inflation rate below 2 per cent.”

So, rather than leading to prosperity for all, monetarist central bank policy has actually led to greater inequality, stagnation for most, and huge rewards for a small percentage of the population. In fact, the bias towards investment helps push more money into the market and helps fuel the kind of speculative vampire capitalism that is practiced by private equity firms.

Free marketers may well say, well, that’s the way the world goes. But we need to understand, from a market point of view, why this central bank policy of keeping inflation low is a problem, it is because it fundamentally misprices risk.

Work is a low-risk, low-reward way of getting a return for your efforts: you will get out what you put in, (or a little more) but you are less likely to lose what you put in. Investments are all higher-risk and higher reward: you may get back much more than you put in, or less, or nothing. This is not just intuitively true, it is the warning on every retail investment product: past performance does not guarantee future returns.

A central bank policy that focuses on low inflation flips that on its head: it goes out of its way to ensure that speculative investments, which are inherently riskier, are a sure thing, while lowering the return to labour. It should be obvious that this is totally unsustainable, but it also means that the very institutions that set the ground for the entire economy are saying “black is white, and white is black.” It exposes the vast majority of people doing low-risk work and no investments to higher risk by inducing wage stagnation, while shielding a minority — especially a very wealthy minority — from their higher risks by making money through speculation.

Central bank policy, which provides the ground under which a nation’s entire economy operates, is mispricing risk and distorting the market. It leads not only to lower or stagnant wages for the majority, but denying risk, rather than managing it, only postpones the inevitable disaster while also ensuring it will be even larger when the failure occurs.

It is like trying to improve performance on a steam engine by building it without any safety valves. It allows the pressure to go much higher than it would without the valves, but it sets the system up for catastrophic failure.

In a footnote in The Big Short, Michael Lewis explains that this risk calculation was a challenge for the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA).

“ISDA had been created back in 1986 by my bosses at Salomon Brothers, to deal with the immediate problem of an innovation called an interest rate swap. What seemed like a simple trade to the people doing it — I pay you a fixed rate of interest in exchange for you paying me a floating rate — would end up needing a blizzard of rules to govern it. Beneath the rules was the simple fear that the party on the other side of a Wall Street firm’s interest rate swap might go bust and fail to pay off its debt. The interest rate swap, like the credit default swap, exposed Wall Street firms to other people’s credit, and other people to the credit of Wall Street firms, in new ways.”

The hazards of mixing markets is incredibly important, but totally neglected, including at the national and international level. Indeed, it is taken for granted that free trade is beneficial for both trading partners, but negotiators and political leaders seem resolute in their focus on the benefits of trade while ignoring potential risks.

As Roger L. Martin wrote, the risk of mixing markets is also one of the core problems with shareholder value.

“While it is not possible to entirely eliminate the self-interest of executives, the authors posited that we could better align that self-interest [and] eliminate agency costs by giving agents meaningful amounts of stock-based compensation, actually making them shareholders as well as executives... the theory had the unfortunate effect of tying together two markets: the real market and the expectations market.”

As others have discovered, linking two markets, one high risk and one low risk, does not mean that the low risk one will calm the high-risk one down: risk bleeds from the high-risk market to the low-risk one. If you have two rooms next to each other, one with no fire in it and one where the furniture is ablaze, it is not going to help to open a door between the two with the hope that the room with no fire will quiet the inferno next door. In Canada, we’ve mixed the mortgage market and the housing market.

So - whether you’re better off than 40 years ago or not - now you know why. Because it’s wasn’t just government policy that changed. Everything did.

30 -

There is an inequality rating, where .1 is the optimal and 1 is the worst. I have read that this has been worsening over tge past decade in Canda, US and UK. Comments please?

You wrote: "It is very clearly a kind of moral judgment about who deserves the money..." But... nah! It is an immoral judgement, for precisely the reasons you go on to outline, about where the real value derives from etc. Maybe I'm all alone here, but in my lexicon "moral judgement" means judgement about what is good (and so also about what is "less good" in relative terms when presented with choices), not what derives from an ideology that could easily be false. While no one person can lay claims on what is morally correct, it is not too hard to agree on what is morally false. So at a minimum I'd write that sentence, "It is very clearly a kind of false moral judgment about who deserves the money..."