Better Understanding Modern Monetary Theory

The economists who are talking about "MMT" aren't talking about the way the world *should* be. They're talking about the way world is, right now.

During the pandemic, when the Federal Government’s fiscal efforts essentially kept the Canadian economy from complete collapse, two former Senior Finance Officials, Scott Clark and Peter DeVries, wrote in concern about the lack of apparent “fiscal guardrails,” and “fiscal anchors” during the single greatest public health emergency in a century.

Towards the end of their piece, they write

In that brief sentence, Clark and DeVries are making a number of errors about Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT.

First, having the Bank of Canada lend to the Government of Canada is not Modern Monetary Theory. What they are describing is a “monetized deficit” and it was used by the U.S. to fund 15% of the Second World War and was being used by the Bank of England to support the UK government during the pandemic in 2020.

MMT is not a theory about what we should be doing if we were to accept it. It is a theory that its proponents describe what is already actually happening, right now. Everything that governments and central banks and banks and business are doing right now can be explained through MMT. MMT is descriptive, not prescriptive.

Because MMT argues that money is created in a way that is different than our current economic framework does, it does offer different policy choices, with new opportunities, but also with new risks. Under MMT, there are still jobs not worth doing, investments not worth making, and wastes of time, effort and human endeavour and money.

If we are going to talk about a theory, or engage in discussion around competing ideas, we should at do our best to have an informed debate.

How Money is Created, According to MMT

It is important to understand the paradigm of money creation in MMT, and banking, is very different than neoclassical economics - so much so, that it is a challenge to wrap one’s head around.

Part of it is there are two different ways of thinking about money. One is that people who still tend to think of money as being material objects, like coins or cash, when you can also think of money as an accounting entry.

It’s clear that most money in the economy is not cash. When you consider all the money in the economy - trillions of dollars in Canada - that money is not in the bank vaults of the country. Instead, there are accounting entries that represent the money.

In one important sense, MMT is easier to understand now that our experience of handling money transactions in a country like Canada has so much of an electronic, or digital aspect.

It has not changed the nature of money - it has revealed it, because MMT theorists argue that’s what money is - it is something created by government that can be used to pay taxes. If you can’t pay taxes with it, it’s not money - which is why cryptocurrency is not a currency, and not an alternative to money.

That’s only one side to money creation, however. According to MMT money in the economy is created publicly by government - but it is also created privately by banks. Both matter.

Public money creation

MMT does not say that national governments should create money to spend it.

MMT argues that national governments do create money in the act of spending.

According to MMT, the federal government just spends money into existence. (Only a federal government can do this - not lower levels of government). When that money that is paid back in taxes is “destroyed.”

This is exactly how money was used and taxes were paid for centuries in Great Britain, where money took the form of “tally sticks”.

Tally sticks were widely used as money, right into the 20th century. The idea of a “running tally” or tally sticks is that you make a mark indicating the value on the stick, which is split down the middle, with half going to the lender, and half going to the borrower.

So, this is not about central banks creating new money at all. It is an argument that the federal government creates money by spending it into existence, through its fiscal measures.

Only national governments can do this. Provincial and municipal governments cannot create money and should try to run balanced budgets.

Of course, this is a challenging idea, because we used to have a gold standard where money was “backed” by its gold reserves. This leads to inevitable question - what is backing the price of gold? The reality is that the value of a currency relates to its ability to deliver what you need from it, because you need that currency to buy certain things.

Money is not backed by gold - it’s backed by people, and the ability of institutions, including every aspect of government to deliver value, by enforcing that value through legislation, regulation, contract law, the courts, enforcement, and domestic and international treaties - even extending to “gunboat diplomacy”.

When there is an economic crisis, people still turn to gold, and its price rises, so people dig it out of the ground to sell it, with the idea that with more gold, we can create new money. In his book, the General Theory, Keynes argued that you could achieve the same effect by just printing money, and burying it for people to dig up.

Private money creation

Orthodox economics assumes that banks are intermediaries - middlemen - that every lender has a matching borrower, and since every dollar owed nets out to zero, the financial sector is not modelled.

MMT suggests that aside from public money created by governments, most money in the economy is created privately by banks in the act of lending - mostly in the form of mortgages. When the debt is repaid, the money is “destroyed” and the interest is the profit. The technicality of what happens is that banks create credit when a borrower offers a promissory note - an IOU to the bank.

The bank then creates ‘fountain pen money’ in the customer’s accounts. Your mortgage is also the bank’s asset - those are the two sides of the ledger.

If you want to understand it, the bank creates the money in your account, and has it as money owed in their accounts. As you pay it down, the debt disappears - it’s destroyed. And the bank makes its money on fees and interest.

This may seem hard to wrap your head around - but when you think of money as being a kind of information technology, where you create, copy, paste and delete - it helps to make a bit more sense of it.

There is a quite a good summary of Money Creation in Modern Monetary Theory, as written by analysts at the Bank of England, here:

banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them, and nor do they 'multiply up' central bank money to create new loans and deposits… This article explains how, rather than banks lending out deposits that are placed with them, the act of lending creates deposits — the reverse of the sequence typically described in textbooks. (McLeay, Radia, and Thomas 2014, p. 14. Emphasis added)

This is very different than the “money multiplier” model of banking, which argues that banks "expand the money supply” through re-depositing and re-lending.

This argument was also supported by the Deutsche Bundesbank

It suffices to look at the creation of (book) money as a set of straightforward accounting entries to grasp that money and credit are created as the result of complex interactions between banks, non- banks and the central bank. And a bank's ability to grant loans and create money has nothing to do with whether it already has excess reserves or deposits at its disposal. (Deutsche Bundesbank 2017, p. 13. Emphasis added)

The same statement was also made by the Senior Vice President of the New York Federal Reserve Alan Holmes, in 1969.

Banks therefore face no hard limits in the money they can create - they face constraints like competition, regulation, interest rates. The real limit is the borrower’s breaking point.

Of course, it’s odd to think of money this way, when people think of money as something that must be valuable, when it is something that only represents value. Cash money in Canada is made of plastic. There is no difference in real value between a few rectangles of tough plastic with printing on them, but the represented value can vary from $5 to $1000.

It is this private debt - money creation by banks, mostly for speculation on non-productive assets (property, but also other assets) that largely drives the business cycle.

“Easy money” in the form of low interest rates means larger mortgages, so real estate prices rise based on ability to borrow, not the ability to pay.

Because the private money is being created in the form of debt, it is inherently destabilizing.

This is the other side of MMT that is so important - that money is not just created by government or printed into existence by Central Banks. Rather, private banks create money through the act of lending, through extending credit.

We should also remember, the idea of private money creation should not be that strange. It is unquestionably a historical reality that has occurred for centuries, and has driven a number of financial and economic crises, including hyperinflation in Germany in 1923.

This paints a very different picture of the dynamics of the economy, and what drives inflation and other cost pressures.

It’s also a colossal amount of new money being created by private lenders - 95% - is created for mortgages.

Financial crises start in the financial sector, and they are directly related to private money creation in the form of mortgages, and housing bubbles.

Real estate is not included in inflation, but higher property, financing and insurance costs all add to the cost of overhead and drive up the cost of living and doing business. As a result, workers either cannot afford to buy a home, or they need to be paid much more, making the businesses that hire them less competitive in foreign trade.

Another significant difference is that because of interest, there is no one-to-one relationship between borrower and lender.

The whole nature of debt is that it takes out more than it puts in. There is the original sum that was lent, and a growing claim against it.

Even outside of MMTs claims around private money creation, a borrower will face an always-growing claim against a fixed sum.

The result is that private claims on money loaned will inevitably outstrip the economy’s ability to pay, unless new money is being injected into the economy.

What has happened over the last decades is that governments have left money creation to private banks, and have left monetary policy to central banks, and the goal has been to shrink government, cut taxes, balance budgets or run surpluses, while lowering interest rates to enable private borrowing.

The result is a massively overleveraged consumer, with over 175% of their income in debt, and private debt is higher than 100% of GDP). It has been argued by economists that it is this debt overhead that is the cause of economic stagnation, growing inequality, and de-industrialization.

As a consequence, Canada and the world are facing an insolvency crisis that was widely predicted, including by William White, a Canadian economist who worked for the BIS, who also predicted the Global Financial Crisis.

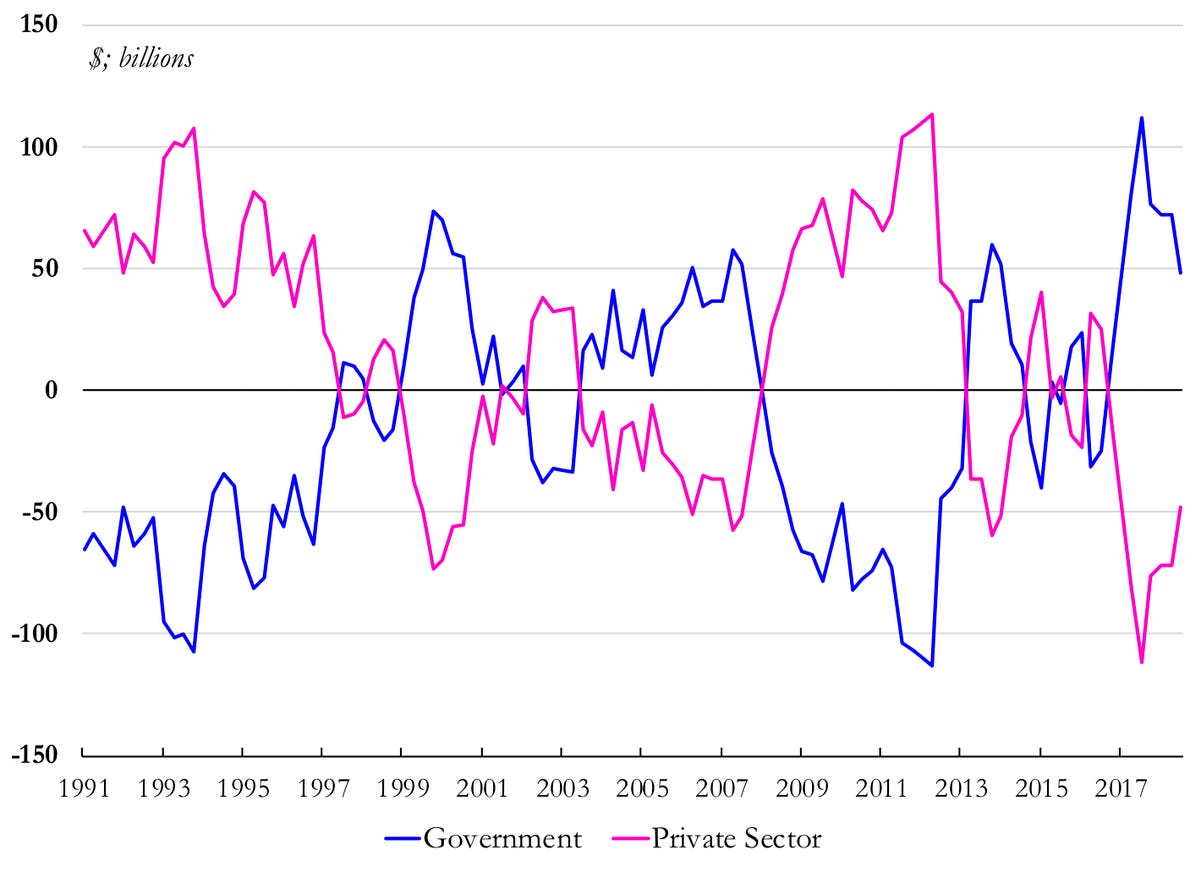

Public debt and private debt mirror each other

This is one of the most important insights - not unique to MMT, but it is critical for policymakers - the relationship between public debt and private debt.

The relationship is fairly simple - when governments cut and reduce their debt, the costs don’t disappear.

When governments run surpluses, and deleverage, it has the effect of shrinking private sector assets, and the debt is shifted to the private sector instead.

The debt that is cut on government books is shifted to private sector, and when the government takes on debt, private sector debt is reduced.

But that deficit - a public liability - is a private sector asset, as this chart shows:

Annual Change in Financial Assets, 1991-2018

Source: Cansim table 36100580. ‘Private sector’ aggregates data for ‘Households and non-profit institutions serving households’, ‘Corporations’ and ‘Non-residents.’ ‘Governments’ is ‘General governments.’ Note: Series is the year-over-year change in quarterly values.

This puts an entirely different perspective on austerity and fiscal conservatism - as well as the challenges of economic recovery after a crisis.

Government debt tends to explode as a result of responding to crises - especially financial crises.

If you have a hot economy being driven by a housing bubble and new mortgages, lots of people are paying taxes. In the downturn, government costs go up with claims while tax revenue from companies and people disappears. If governments run deficits, they are borrowing so that the debt is being shifted from the private sector to the public.

But then what happens? If government then pursues cuts, that debt is transferred back to the private sector - to families, businesses.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, this happened in Japan. After a massive economic boom based on excellence in manufacturing in vehicles and electronics, Japan then had property bubble so massive that Japan was worth 50% of the entire global real estate market. One suburb of Tokyo was worth California. Another suburb of Tokyo was worth all of Canada.

The market and the banks crashed and it took years to figure out just what was wrong.

Japanese Economist Richard Koo called it a “Balance Sheet Recession.”

The economy - corporations included - were so clogged with mania-era private debt that the economy could only achieve growth with continual government stimulus. If it stopped, so did the economy.

The question is how to get out of it? If public sector deficits and surpluses mean you’re just shifting debt back and forth, how do you actually get rid of it?

Between 2008-2013 Lord Adair Turner chaired the UK’s Financial Services Authority, starting at the job within days of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis occurring.

Turner wrote a book about what he had learned and how he thought the world should get out of the mess, saying “We must think fundamentally about what went wrong and be adequately radical in the redesign of financial regulation and macro-prudential policy to ensure it doesn’t happen again.”

In his book, “Between Debt and the Devil: Money, Credit and Fixing Global Finance” Turner breaks down the failure of macroeconomic theories to describe reality, while developing possible solutions for dealing with the crisis. It is an outstanding book.

One of his suggestions is “monetized deficits” which is, in a limited and targeted way, to have central banks pay for some part of government deficits. This is what people think MMT is. It is not - but it is something that is possible under MMT.

“Monetized Deficits” or Central Bank Financing of Government

It’s worth talking about Clark and Devries perception of what MMT is, which is central banks just financing government deficits. I’ve tried to make it clear that MMT is much more than that. It’s about recognizing private money creation and debt as well as arguing that government creates money differently than orthodox economists argue. MMT theorists believe that the federal government just spends money into existence, and destroys the money when it’s paid as taxes, because we’re talking about tokens here - and they cancel each other out.

However, they are also mistaken when they say the idea of Central Banks financing government is “unproven.”

At the time they were writing, in spring 2020, the Bank of England in the UK was doing exactly that, with the endorsement of the Financial Times.

There are historical precedents for “monetized deficits” in Canada and the U.S. 15% of the U.S. war effort in WWII was paid for by having the Federal Reserve buy treasuries.

After the war, some economists recommended 100% reserve banking, and no lesser light than Milton Friedman recommended that federal governments continually run small deficits, financed by central banks, in order to keep the economy running smoothly.

It should be recalled that FDR’s New Deal was not just about government running deficits to get the economy going again. It was about new laws and regulations, crafted specifically to address practices that ranged from hazardous to criminal that caused the Great Depression, as well as a new and better understanding of the way the economy worked.

And most of Canada’s federal debt is held by Canadians, which is positive.

Part of the argument for Bank of Canada financing of debt is based on this scenario:

The Government of Canada is raising money to cover this year’s budget by selling bonds, and a US investor wants to buy $10-billion Canadian dollars worth of those bonds, at 5%. The US Investor has to convert their currency - they have to go to the Bank of Canada and buy $10-billion Canadian dollars. The Bank of Canada just prints that money - or “creates it” and gives it to Government, in exchange for bonds that commit to repaying that money back with interest.

The question is - if all the transactions are in Canadian dollars anyway, and the Bank of Canada is printing new money, why do we need the foreign investor? What difference does it make to the Canadian economy or the domestic impact when in both cases, the Bank of Canada is creating $10-billion and giving it to the Government of Canada. It is the same transaction.

The argument is that there is no actual reason to go to the private sector or foreign lenders to borrow money to finance a domestic deficit - it can be borrowed from the Bank of Canada. It could then be repaid, and the money would be “destroyed”, taking it out of circulation, which would avoid inflation.

So, the assumption is that we may have to go to a foreign investor to sell Canada’s bonds. To borrow Canadian dollars, bond purchasers have to convert their currency into Canadian dollars, which are created by the Bank of Canada. So the net effect is arguably the same - with the difference that there is less risk because there is no exposure to changes in international exchange rates.

So, let’s be clear. Monetized deficits are something that are possible under MMT, but they are not what MMT is about.

Modern Monetary Theory is about having an economic theory of the economy that does a better job of explaining how money is actually created and handled in our economy, than the models we are using, because they are out of date and don’t work.

The question for people who want to argue about what the consequences of Modern Monetary Theory might be, consider two things.

First, as far as MMT theorists are concerned, they are describing the economy as it exists, right now. So, before we consider implications, ask yourself, does this actually do a better job of explaining how money and our economy works?

This is a change in theoretical perspective, not a change in any policy.

Some of the ideas are challenging, because it is very different from the way we usually think about money, and how we’ve been taught to think about it.

Does it do a better job of describing the way things are actually working?

That leads to the second part. Well, if that’s the way things really work, doesn’t that mean we can do a whole bunch of things we’re told are impossible?

Because two of the consequences of accepting MMT may be very profound.

Because MMT gives an alternative explanation of the economy that basically overthrows both fiscal conservatism as well as “supply-side” or trickle down economics.

So there is political and ideological opposition as well.

MMT breaks fiscal conservatism

MMT breaks fiscal conservatism, which as an ideology that embraces austerity and cuts and a minimal government, because it assumes that a government with its own currency depends on the private sector for revenue.

This is an area where MMT is very clearly accurate. While it is not currently accepted ideologically, the Bank of Canada Act establishes a mandate that is very broad - as you might expect, since it was created in the middle of the Depression.

“WHEREAS it is desirable to establish a central bank in Canada to regulate credit and currency in the best interests of the economic life of the nation, to control and protect the external value of the national monetary unit and to mitigate by its influence fluctuations in the general level of production, trade, prices and employment, so far as may be possible within the scope of monetary action, and generally to promote the economic and financial welfare of Canada.”

When central banks perform “quantitative easing” what they are doing is creating money - “printing it” - and giving it to banks, while taking investments that are tanking off the banks’ hands. That way the banks could keep lending.

The reason central banks are printing new money to do this is because according to the neoclassical economics and models, the banks are in a “liquidity trap” - they are short on money. MMT can recognize that this is not a liquidity crisis, this is an insolvency crisis, because of crisis levels of private debt.

MMT Breaks “Trickle-down” or “Supply Side” Economics

The basic principle of supply side economics is that you have to build wealth before you can distribute it. But MMT states that the federal government creates money in the act of spending, and that private banks create money in the act of lending.

You do not have to have savings first. Supply side economics falls at the first hurdle.

Here too, there is endless historical evidence that, innovation and industrialization and infrastructure, created modern North America, in all its good and bad forms, often at incredible public expense - and incredible public benefit.

Again, this is an evidence-based observation. This is our economic history.

Policy Implications of Embracing MMT

While our current fiscal ultraconservative age focuses on making the most of money, it could be argued that MMT would allow us to make the most of people and their potential.

MMT theorists make it very clear, they don’t want inflation either. They want a more stable economy. It’s not about government running everything or the private sector running everything.

It’s about the total capacity of the economy - and that is one of the constraints. You don’t want to overheat the economy and cause inflation, you don’t want to distort the economy by pumping too much money into a bad investment.

So, you’ve still got constraints, but the limits are different. You can still have entrepreneurs, markets, private enterprise and ownership. And really, MMT is about stability, and a key part of that is discipline. So it can’t be and should not be a free-for-all. If times are good, then interventions are minimal. It’s not about public vs private sector. Entrepreneurship and risk taking still matters. There would need to be new regulation but the goal is a maximally productive society, where we’re giving back to the environment.

MMT is also a theory that is flexible in that it applies as well in emergencies as it does in times of relative peace. It could help restore financial stability, because it is a more responsive financial insurance scheme at the level of an entire economy. It’s possible to offer a “job guarantee” for example.

We could examine alternate ways to deflate the housing bubble.

So under MMT, the limitations are the capacity of the economy - labour, capital investment, workers, the environment and energy, while avoiding inflation. Those are all serious limitations, but it opens up new opportunities in policy innovation, along with the resources to implement it.

Of course, none of this can occur in a vacuum and in today’s world, any country trying this on its own might face some challenges, including challenges when it comes to their exchange rate.

MMT offers an interesting new diagnosis, and opens up new possibilities for treatment for our ailing economy - rather than the central banks’ current, more medieval approach, which is to believe the solution to every problem is a bloodletting. Even when you know the diagnosis, the treatment is another thing entirely. An explanation is not the same thing as a solution.

There is a final point - which is Clark and Devries’ argument that MMT being “unproven”.

We don’t have to agree with MMT.

We should question why we are still clinging to outdated neoclassical economic models that have clearly failed, and are still failing.

The current theories by which we are operating our economy not only failed to predict the global financial crisis in 2008, which resulted in tend of millions of jobs lost - those theories created the conditions for the financial crisis in the first place.

In the aftermath of the crisis, governments across the world engaged in further austerity, resulting in cuts to services, that lasted years. At the same time, central banks were bailing out the financial sector and investors with trillions of dollars in newly printed money “quantitative easing” - in the U.S., Europe, Canada.

We are now in an inflation and insolvency crisis, severe political turmoil around the world, and a housing crisis in Canada.

There are very serious organizations and individuals, like the Bank of International Settlements, and economists like Paul Romer, William White, Adair Turner and many more, who have continued to urge reform, because what we have now is not working.

-30-

Comments - Better Understanding Modern Monetary Theory (substack.com)

Another excellent column. But I have a few quibbles.

1. MMT is not new. It is essentially Keynes. I assume you have read a lot of Steve Keen who says he is Keynesian and promotes that thinking and decries neoclassical economics. Nonetheless, MMT makes many good points and wants to improve the lives of everyone. I do think it has some eccentric ways of putting positions that Keynesians and Keen would not disagree with.

2. I disagree with MMT' choice of saying governments create money by spending it into the economy. It is true that with taxes (let us just talk provinces here so as to avoid MMT version of tax collection), we slow the economy and the taxes need to be spent to restore demand. But the way our money system now works, almost all the money creation is through the banks as you have noted with this link

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Furthermore as the link says, central bank money other than banknotes, can't be spent into the economy. So MMTers are stuck with a QE system which pays interest to banks for their settlement balances. "Reserves can only be lent between banks, since consumers do not have access to reserves accounts at the Bank of England.(2)"

3. MMT seems to be incorrect about its 'issuer' position. Canadian academic and Fed VP David Andolfatto says something that sounds MMTish - "When the interest comes due, it can be paid in legal tender—that is, by printing additional U.S. or Federal Reserve Notes. It follows that a technical default can only occur if the government permits it." But he includes what could make the MMT position true. The Fed would have to provide all the money in banknotes, because reserves are only useable by the banks.

https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/fourth-quarter-2020/does-national-debt-matter

4. Andolfatto elaborates here -

"All the money we use today consists of bank liabilities, either private or central. Let me label this private bank digital currency (PBDC). I’ve also mentioned that CBDC exists in the form of reserves held in accounts with the central bank. Reserves are counted as a liability of the Federal Reserve. The third type of money takes the form of small‐denomination paper bills issued by the Federal Reserve. Let me label this central bank paper currency (CBPC). These too are counted as liabilities of the Fed.

The way things presently stand, everyone in the world is permitted access to CBPC, the paper component of the Fed’s balance sheet. However, only banks (and a few other agencies) are permitted access to CBDC, the digital component of the Fed’s balance sheet. Why is this the case?"

https://www.cato.org/cato-journal/spring/summer-2021/some-thoughts-central-bank-digital-currency

Good article, echoing what Prof Steve Keen ( The New Economics - a Manifestos) and Stephanie Kelton (The Deficit Myth) have been saying for a few years now.

I am suspicious of your graph; it is too much an exact mirror image to be credible as being constructed from real data sets.

On reducing the housing debt; Keen advocates a debt jubilee in the form of a direct payment to mortgagees or, if the home is already owned free and clear, a payment that must be invested.

He also advocates a parallel carbon currency that would be paid to everyone but has the advantage of encouraging redistribution of wealth from rich (high carbon emitters) to poor ( low carbon emitters).