Central Banks: Can Engines of Inequality Become Engines of Growth?

A version of this paper was presented at the Post-Keynesian conference in Buffalo, NY in June 2017.

Writing in The Guardian on October 25, 2016, Jeffrey Frankel, a former economic advisor to Bill Clinton, argued that governments alone should be addressing inequality, while central banks should be limited to concerns of ‘an overheating economy and future financial instability, not inequality’ (Frankel 2016).

However, there are strong arguments that central banks have been engines of inequality and that the policies Frankel endorses have contributed not only to decades of growing inequality, but to the global financial crisis and the tepid recovery that followed; moreover, they could be sowing the seeds of another crisis to come. As Ari Andricopoulos argues, central banks ‘have consistently sought to revive the economy by increasing debt and raising asset prices’ (Andricopoulos 2016, 38).

By the same token, central banks have the capacity to reduce inequality and spur growth, and there is both theoretical and empirical support that they can do so effectively without significant inflation. In addition to reviewing the theoretical and empirical evidence, this paper seeks to clarify how, due to inequality in income and wealth, the focus by central banks on low inflation, while leaving money creation mostly to private banks, can lead to inequality and stagnation.

Keywords:

Introduction

At the time of writing, there is growing concern about ‘secular stagnation’ as global growth forecasts are continually downgraded. While there is anxiety about inequality, jobs, stagnant wages, a lack of global growth, and the shrinking of the middle and working classes in the developed world, there is little in the way of action. Jeffrey Frankel, a former economic advisor to Bill Clinton, argued in The Guardian of October 25, 2016, that if anyone is to address inequality it should not be central banks, who for their part, are ‘supposed to be concerned about an overheating economy and future financial instability, not inequality.’ (Frankel 2016)

What does Frankel mean? After all, don’t governments and central banks want to create more jobs and watch people’s incomes rise? The answer is no.

Since the 1970s, central banks (and governments) have been overwhelmingly concerned with one thing: inflation. If it looks like the economy is heating up - if too many people are getting jobs or raises and it looks like prices might go up, then central banks will step in to cool things off - by putting people out of work, driving down wages and bankrupting businesses. In downturns, they lower interest rates to encourage borrowing, which tends to drive up asset prices.

Inflation has been low for so long that we might well ask why central banks are still primarily tasked with taming it. Inflation is called ‘the cruelest tax’ because (we are told) people who have scrimped and saved their pennies see their purchasing power dwindle over time. For workers, inflation is supposed to be, at best, a wash: if their wages rise, prices will too. The reality is much more complicated.

In The Big Trade-Off, Arthur Okun wrote that, ‘The crusade against inflation demands the sacrifice of output and employment.’ (Okun 1975, 2) Ha-Joon Chang, in his book Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism, elaborated:

a tough control on inflation is a two-edged sword for workers — it protects their existing incomes better, but it reduces their future incomes. It is only the pensioners and others (including, significantly, the financial industry) whose income derive from financial assets with fixed returns for whom lower inflation is a pure blessing (Chang, 2008, p. 151).

The general perception of inflation may be that it carries too many negatives and too much risk: lost savings for pensioners along with wage and price increases cancel each other out or make companies, or the economy, less competitive. The perception in Economics 101 is if all prices and wages doubled, the economy would be no different, but when it comes to debt, this is not the case.

Even if prices and wage exactly doubled, apparently cancelling each other out, there is still a potential benefit - inflation makes debt easier to pay off, for businesses, governments and individuals alike. Low inflation thus favors not only owners over workers, but lenders over borrowers. The result is that the central bank policy of suppressing inflation – even during deflation - is an engine of inequality and risks having the opposite effects to those that are intended.

The perception is that wage and price inflation is necessarily bad for growth and for the poor: of course, this depends on whose wages and what prices are rising. As Ha-Joon Chang points out, ‘there is inflation, and there is inflation.’ (Chang, 2008, pp. 149-150) There is inflation that organically accompanies growth, and then there is hyperinflation. [1]

Chang writes that Brazil’s inflation was 42% a year in the 1960s and 1970s, at a time when it was one of the fastest growing countries in the world, with per capita income increasing at 4.5% per year:

‘In contrast, between 1996 and 2005, during which time Brazil embraced the neoliberal orthodoxy… inflation averaged a much lower 7.1% a year. But during this period, per capita income in Brazil grew at only 1.3% a year.’ Korea and China also had high inflation, which coincided with extremely rapid growth (Chang, 2008, p. 150).

Chang also cites a study by Michael Bruno and William Easterly, two World Bank economists, showing that ‘below 40%, there is no systematic correlation between a country’s inflation rate and its growth rate’ (Chang, 2008, p. 150). As the saying goes: the dose makes the poison.

The singular pursuit of price stability seems to have two serious flaws. One is that a failure defined by Goodhart’s Law: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

Goodhart’s Law: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

The other us that since price stability benefits owners and finance at the expense of workers, in the long run it throttles demand.

Suppressing employment and wage increases for people who work for a living, who comprise the vast majority of any population, while attempting to ensure better returns for bondholders is an inherently unstable strategy, especially when paired with central banks’ long-standing approach to stimulating the economy, namely lowering interest rates to encourage borrowing and spending, which has the effect of driving up asset prices.

Making it easier to lend but harder for borrowers to pay back their debts makes defaults and financial crises more, not less likely. As Minsky has argued, private debt causes financial crises – especially when debt is driving an asset bubble (Keen, 2011, p. 353). Assets are generally excluded from measures of inflation, even while the cost of housing – which, as shelter, is a necessity of life, and not merely an investment – becomes unaffordable.

Andricopoulos argues that the long-term effects of central banks lowering interest rates have distorted the entire economy. Returns to labour and capital have shrunk, as returns to finance have increased as investors pursue rent-seeking for higher returns. High private debt levels have resulted in slowing economic growth as more and more income is used to pay off debt, constricting demand (Andricopoulos 2016, 31). As returns elsewhere in the economy slow, debt-driven gains, especially in real estate accelerate until borrowers reach their limit.

It does not have to be “speculation” by investors looking for a quick buck – Adair Turner notes that, “Keynes called transactions in already existing assets “speculation”’ (Turner 2016, 118). As Keen writes, “Once an economy has a substantial level of private debt to GDP, and that ratio is growing faster than GDP, then a stabilisation of the ratio will cause a serious recession, even without any reduction in the rate of GDP growth.” (Emphasis in the original) (Keen 2017, 83))

While waves of mortgage defaults can trigger a financial crisis and bank failures, even those who don’t default may be underwater on their debt and technically insolvent. One consequence is Fisher’s paradox – “The more you pay, the more you owe.”

Andricopolous argues the economy needs to be rebalanced but the only way to return to growth is to reduce the private debt. It is possible to do so by having government run large deficits, but as Adair Turner points out, this does not reduce the debt, but shifts it from the private to public sector. To pay down the debt, Andricipoulos and Keen argue – as does Adair Turner, with caution – that central banks could assist in reducing private debt levels.

Keen argues for what he calls a ‘modern Jubilee’: a ‘helicopter money drop’ of central bank funds directly to citizens with the condition it be used to pay back debt first (Keen, 2012), Andricopoulos argues we should ‘rebalance the economy using large, preferably monetised, government deficits’ (Andricopoulos 2016, 1), which Keen has also endorsed. For his part, Willam Buiter prepared a paper that argues that as long as three conditions are fulfilled[2], helicopter money will always work (Buiter 2014, 1).

The concern is that central printing money will result in inflation or currency devaluation: but this concern may be misplaced because of a an alternate way of looking at the role of banks in the money creation.

While Robert Lucas wrote that “Of the tendencies that are harmful to sound economics, the most seductive, and in my opinion the most poisonous, is to focus on questions of distribution,” (Lucas 2004). Ignoring distribution within an economy is to ignore reality.

By exploring the real-world distribution of assets and income, we can explain why central bank policies have effectively been counterproductive. As Joseph Stiglitz put it, central banks are ‘oblivious to the distributional consequences of monetary policy’ (Stiglitz 2012, 243), and in neoclassical economics discussion of inequality is considered a taboo:

A better understanding of income and wealth distribution helps explain how monetary policies favour owners over workers; this helps to show how harsh anti-inflationary policies fundamentally misprice risk of investment vs labour. We can also see that the historic success of monetary intervention in the past, particularly in Canada, provides historic evidence than the policy can effectively drive growth without serious inflation.

1. Understanding distribution: inequality, the 80/20 rule and the concentration of assets and Income

When inflation is called ‘the cruelest tax’, the people being cruelly affected are usually assumed to be low-income seniors living on fixed incomes, being robbed of their savings.[3] While no one would wish to dismiss the concerns of low-income seniors who have saved for their retirement, the number of people in this position is depressingly small. The majority of people, even in developed countries, have negligible or no savings for retirement. A 2016 study suggested 69% of Americans had less than $1,000 in savings (Williams 2016).

In contrast, stock ownership is incredibly concentrated: in the U.S., the top 1% owns 38% of equities, and the next 9% owns 43%. Together, the top 10% of the population owns 81% of all stocks (Domhoff 2013). In Canada, the concentration of wealth is less, with the top 20% owning 67% of all assets.

This is why Ha-Joon Chang’s point, that the only people for whom low inflation is a ‘pure blessing’ are those entirely outside the labour market, is so important. A policy that focuses on increasing the value of assets means that in the U.S., 80% of benefits will go to the top 10%. Price stability assumes that elevated inflation is bad for everyone and that the distribution of ownership is much greater than it actually is.

Anyone who has followed the inequality debate will be familiar with the concepts of ‘the 1%’ and the ‘99%’, or Oxfam’s statistics that the 62 wealthiest people in the world have more wealth combined than the bottom 50% of humanity - 3.6 billion people (Oxfam 2016).

1.1 Understanding inequality as concentration

One issue with the debate around economic ‘inequality’ is that people generally accept as a fact of life that since humans are all different, they are bound to be unequal to some degree. Some are richer, some poorer, some more skilled, some less so, and it is either accepted or argued that people are richer for meritocratic reasons. The concept of “purchasing power parity” also recognizes that economies exist as local “ecosystems” where costs are relative. The idea of “inequality” fails to convey the scale of concentration of wealth income among a very few. “Concentration” of wealth and income may be a better way of framing and understanding the issue, but common approaches to inequality fall short, precisely because they use averages to measure concentration.

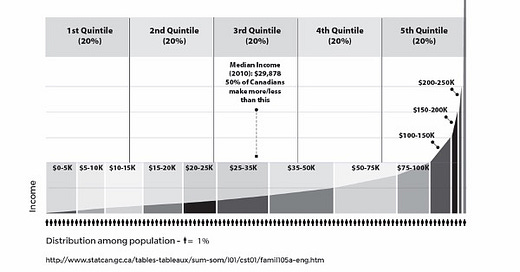

For example, it has been routine to divide up populations into five equal ‘quintiles’ or ten ‘deciles’, then define social mobility as moving up between quintiles. A bell curve may be assumed, with a broad middle class with most income and wealth, and a relatively small number of people who are either poor or wealthy.

This approach to analyzing income and wealth is flawed. When we talk about the 1%, or the 0.1%, it is because income and wealth inequality roughly follow an 80/20 rule, a so-called ‘power law’ (to the power of ‘x’, not because it is about power).

For almost any given population, the distribution of income and wealth across the bottom 80% is surprisingly even, sloping up gently. When inequality starts to rise, it goes up in leaps and bounds, like a Richter scale, with almost all of the change concentrated in the top 20%.

Fig 1. Individual Incomes & Inequality in Canada (The Author) (Statistics Canada 2013).

Please note: the top peak of the graph has been capped at $1-million. An accurate depiction of this one data point would be far higher, especially if total compensation were included (bonuses, shares, options, pensions and any other payments in addition to base salary). Household incomes show a similar pattern of inequality.

Consider this chart, derived from 2013 Statistics Canada data. The curve of income slopes up gently for approximately 90% of the population, before taking an extremely sharp turn upwards.

Defenders of the status quo who seek to dismiss the significance of growing inequality, for example, may emphasize the mobility of individuals moving between quintiles, but this is misleading. In Canada, for example,

An individual who goes from the 15th percentile to the 60th percentile – moving past 45% of their fellow citizens –would see an increase in their income of about $30,000 a year.

An individual who goes from the 97th percentile to the 99th percentile, past 2% of their fellow citizens - would see an increase of $50,000 a year.

A person moving from the bottom of the 1% to the top would go from making $200,000 a year to over $50-million (if all compensation is included).

There is a greater absolute change in income within the top 1% than from 0%-99%. The ‘poorest’ person in Canada’s 1% earns around $200,000 per year, but the richest will make several million in income per year, though total compensation for some CEOs in Canada runs to tens of millions (Mackenzie 2016).

Figure 2. Wealth in Canada 2012. Chart by the Author (Statistics Canada 2013).

The concentration of wealth also tends to follow a power law, except it is greater than the concentration of income. This is, in part, because there are people who work for a living who own nothing, or may well have negative net worth, but nevertheless have income. At the top, property owners are also rentiers, shareholders and financiers: they earn income from rents, dividends, and interest from the rest of the population paying those fees: the result is an upward transfer of income. This is even more accentuated since borrowers with no property and low income will face higher interest payments.

80/20 means that 80% of the population owns 20% of the assets, but this holds true for smaller segments of the population, with 20% of the top 20% holding 80% of that wealth, and so on.

Once this is all factored,

the top 0.1% will own 40% of all assets;

the next 0.64% will own 11%,

the next 3.2% will own 13%,

16% will own 16%, and

n80% of the population will own 20% - with many of them owning nothing at all, or having negative net worth.

This distribution is not always exact - in Canada, the top 20% own 68% instead of 80% of all assets. But this power law explains why the 0.1% and the 1% own and make so much. Under 80/20, the top 5% owns over 60% of all assets, and the average difference in wealth between the bottom 80% and the top 0.1% is 500 to 1 - a proportion recognized by Adam Smith:

‘Wherever there is great property there is great inequality. For one very rich man there must be at least five hundred poor, and the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of the many.’ (Smith 1776, 901-902)

2. The origin of the 80/20 rule: Vilfredo Pareto, the ‘Theoretician of Totalitarianism’

The origin of the 80/20 rule bears mentioning. It was discovered by Italian sociologist and engineer Vilfredo Pareto, a pioneer in the use of mathematics in economics. His ideas are part of introductory economics and essential to the concept of ‘Pareto efficiency’ or ‘Pareto optimality.’

Mandelbrot and Hudson note that when Pareto discovered his ratio of wealth and income, he thought he had discovered ‘a social law,’ something ‘in the nature of man…’

“That something, though expressed in a neat equation, is harsh and Darwinian, in Pareto’s view: ‘There is no progress in human history. Democracy is a fraud... The smarter, abler, stronger and shrewder take the lion’s share. The weak starve, lest society become degenerate.’ One can, Pareto wrote, ‘compare the social body to the human body, which will promptly perish if prevented from eliminating toxins.’ Inflammatory stuff — and it burned Pareto’s reputation. At his death in 1923, Italian fascists were beatifying him, republicans demonizing him. British philosopher Karl Popper called him the ‘theoretician of totalitarianism’” (Hudson and Mandelbrot 2004, 153-155).

It is also remarkable that while Pareto’s concepts are a universally accepted part of modern economics, his fascist past has been bowdlerized. It is hard to imagine Karl Marx’s ideas being taught without the mention of the calamitous failures, atrocities and famines of totalitarian communism in the Soviet Union or China, though Marx died in 1883, decades before his adherents sought to implement his ideas in the USSR or China. Pareto was appointed to the Italian Senate by Mussolini and the fascists, though he died before taking his seat.

Even Pareto’s concept of efficiency, which is considered shorthand for “economic efficiency” has a bias toward ever-growing inequality and against redistribution. It is not in any way a mathematical or economic measure of the use of efficient resources for an economy as a whole – energy, labour, time, or resources. Rather – despite Lucas’ warnings against talking about distribution - it is a way of assessing distributional fairness which defines ever-growing inequality as efficient, and reducing inequality as inefficient.

Pareto efficiency appears to have a concern for fairness, because it asserts that no person in a system should be worse off, and as such appears to imply the need for a safety net or compensation for losses if they occur.

However, initial conditions of inequality and imbalances in bargaining power that occur as it increases aren’t taken into consideration. An economy where all the gains of economic growth accrue to one person while everyone else stagnated is considered “efficient”, as is an economy where all the gains accrue to one person, and everyone else loses – so long as they are compensated for their losses back up to the level of stagnation. However, an economy where everyone gained but the single wealthiest individual lost $1 would be considered “inefficient” – unless the wealthy individual were made whole again.

Pareto efficiency therefore defines growing inequality as “efficient” and addressing it as “inefficient” without any consideration on impacts on the functioning of the economy, growth, or demand. It is a shameful abuse of the term “efficiency” by the economics profession (the other being the “efficient markets hypothesis”) which is divorced from reality and cries out for reform.

3. The theoretical failure of anti-inflationary policies: mispriced risk

The unspoken implication of central banks intervening in the economy for fear of inflation is that if unemployment is getting so low that wages may rise and cause prices to rise, central banks will intervene with recommendations that may increase unemployment.

One might well ask why it is, as a matter of public policy, that a branch of government has a mandate that goes out of its way to protect the investments of a few at the expense of the rest of the population. However, there are certainly economists and others who will argue that greater inequality does not matter, because the added gains in wealth are good for the economy as a whole. The supply-side argument is that by stabilizing, enhancing and increasing the wealth of a few, it provides capital for the purpose of investment into new businesses, which will create more employment, because lower-cost goods give even people with modest means more purchasing power.

The supply-side argument, however, has been seriously undermined by modern theories of money creation, as recently articulated by the Bank of England, which makes it clear that banks simply create money in the act of lending, and that it is destroyed when it is paid back (2014). This is not a new argument – it was articulated by the Senior Vice President of the New York Federal Reserve, Alan Holmes in 1969 (Keen, 2011, pp. 308-310), Adair Turner (Turner 2016) and others.

It is, however, radically different from the accepted description of how banks work, with equally radical implications. In neoclassical economics, debt, banks and money are not modelled. The basic model of a bank as intermediary states that banks make loans from existing money – deposits. Money is created by central banks, and debt as a whole net to zero because for every borrower there is a lender – implying that money, debt, banks and the financial system must therefore have no impact.

The modern theory of money creation is very different. Almost all new money in the economy is created by banks in the act of lending, almost all of it in the form of mortgages that drive up the price of real estate, rather than loans to business for productive purposes. Deposits are loans to a bank, and banks reserves are used mostly to settle accounts with other banks. When loans are repaid the money is “destroyed”.

Businesses and individuals apply for loans and banks create ‘fountain pen money’ in the customer’s accounts: the loan itself is an asset on the bank’s books, and no reserves or deposits are necessary to lend, any more than writing an IOU.

If the premise of supply side economics is that savings leads to investment, which leads to employment which leads to demand, it is a chain that has been broken at its first link. No deposits, or savings at all are required for a bank to create a loan. It also implies very different results should central banks engage in printing money, depending on how that money is used. The money supply is thought of as a fixed amount, and following that assumption, that if central banks add to the money supply, it will cause either inflation or currency devaluation. There are several ways in which this is mistaken – first, because money is being created privately as well as publicly; second, because newly created money that is used to pay down debt is destroyed - leaving the economy without adding to the money supply, devaluing the currency, or adding to inflation; third, because money spend on something new, rather than speculation on existing and limited properties, goods and services, will tend not to be inflationary.

This why Keen’s Modern Debt Jubilee or monetized deficits are not as high risk as perceived, if publicly created money is being destroyed at banks. Bailing out debtors kills two birds with one stone.

3.1 Work as risk-taking

If we accept the evidence that ultra-low inflation policies suppress income and output, we should consider why the policy is wrong, not just from a political or moral view, but from an economic one, which is that it misprices risk.

Investment is considered a form of risk-taking, work is not. Despite the central premise that in a market economy, both sides of an exchange are better off because of a trade, labour is generally treated as a commodity or a cost to be minimized, with output to be maximized. Wages are seen as a one-way benefit to labour, while costs and risks to an employee are routinely ignored.

If we consider, even for a moment, what work means to the point of view of an employee, we can see that it involves taking risks in time, effort, energy, expenses, giving up other possible opportunities and occasionally very real threats to personal health and safety – including the risk of disability or death – in exchange for labour that creates value for an employer. The labourer’s work and risk creates value for the employer in exchange for a wage.

Work may be perceived as a ‘sure thing,’ but this is not the case. The fundamental uncertainty of our existence means that there is no information from the future: that is what makes it the future. If something is absolutely certain, the degree of risk-taking involved is zero – therefore, the reward would be zero.

Work may well be a low-risk, low reward venture for individual workers but the level of risk taken is never zero. This is made more clear in the instance of business failures, when workers who may have contributed to the creation of a firm’s value end up with unpaid back wages or loss of benefits in the event of a business failure.

We need to be clear on terms for a moment, since there is confusion among laymen at least about the distinction between risk, uncertainty, and risk-taking.

Risk is a calculation based on known probabilities, whereas uncertainty means there is missing information.

Risk-taking means deploying a strategic activity which may result in a gain or a loss.

There is a twofold difficulty with the idea of risk. One is that it has a hidden assumption that the past is known, and that nothing new can happen in the future.

This is anti-innovation, but also clearly wrong. There are always unknowns, even when the possibilities are completely known: we know that a coin toss has one of two possible outcomes, but we still do not know what the result will be when we flip it.

The idea of risk-taking and success in business is closely tied to ideas either or skill, fortitude or moral worth, and not of luck. This is in part because we have developed so many technologies that are successful in reducing real-world risk– shelter, energy, transportation, communications, food, water, health and defense. We deploy long-established techniques – which once must have been risky innovations- in order to deal with the hazards the world throws at us.

Why don’t we see work as risk-taking? (Aside from capitalist economics being framed largely in terms of benefits of return to capital?) One reason is that neoclassical economics is focused on exchange and consumption, while production is a black box (Chang, 2014, p. 21). Another reason is that the risk-taking involved in financial investments is obvious and readily quantifiable - as a sum of money that can be written down in a ledger - while work and its associated risks are not. Lost time, energy, and opportunity – even death and disability: they all represent real costs, but they don’t have money attached and they amount to ‘could-have-beens.’ Unlike objects or money, which may be either portable or seizable, work is inseparably attached to the person who does it. When it comes to collection, compelling people to hand over their property is easier than compelling people to work.

In addition to this, work is also a low-risk, low-reward way of getting a return for your efforts: you will get out what you put in, or a little more. You are less likely to lose what you put in – and the rewards from that risk will tend to be widely spread. Many (or all) can participate and get a small return on their risk.

In neoclassical economics, when a worker is laid off or fired it is not seen as a loss – unemployment is seen as a choice (Keen, 2011, p. 262).

In contrast to work, investments are all higher-risk and higher reward: you may get back much more than you put in, or less, or nothing. This is not just intuitively true, it is the warning on most investment products: past performance does not guarantee future returns. Interest is a price on risk - the risk premium on bonds is an indication of the possibility of default. The high-risk and high reward also has a distributional effect: most will lose, and the benefits will be concentrated for a few winners.

If we accept the idea that labour is a form of risk-taking, then we can see that a central bank policy that lowers the return of safe ‘low-risk’ labour while increasing or protecting the values of speculative investments, which are inherently riskier, can distort the entire economy. It exposes the vast majority of people doing low-risk work and no investments to higher risk by inducing wage stagnation and encouraging people to take on debt, while shielding a minority — especially a very wealthy minority — from their higher risks, most of which are likely to fail. Just as important, this is not just true for extraordinary measures like bailouts, asset swaps and quantitative easing – it has been routine policy for decades.

It should be obvious that this is unsustainable, but also that the core mission of central banks, which provides the ground under which a nation’s entire economy operates, is mispricing risk and distorting the market. When it comes to dealing with risk, they are saying, ‘black is white, and white is black.’ By denying risk, rather than managing it, it allows risk to build to catastrophic levels: it merely postpones the inevitable reckoning while simultaneously ensuring that when the failure occurs, it will be even greater. It also serves as an “engine of inequality”.

4. Why do politicians, not central banks, get the responsibility – and the blame – for inequality?

Jeffrey Frankel’s argument that central banks should leave addressing inequality to elected governments is an evasion. Not only have central banks played a role in making inequality worse, but they once played a very different role in reducing inequality and contributing to equitable growth in the past.

As Fig. 3 below shows, inequality has been getting worse in most English-speaking countries since the 1970s – but central banks rarely get the blame. Sometimes, technology and globalization get the blame – changes for which everyone, and therefore no one, is responsible. Notably, neoclassical macroeconomics recognize that changing technology can disrupt the market, but does not recognize that money, debt or banks, exist.

The absence of money and debt is just one of many astonishing blind spots in neoclassical models. Depressions are considered impossible, full employment and the free flow of labour and capital are assumed in free trade calculations, and private debt is considered “a wash”. It should be obvious that high levels of private debt will obviously start to constrain demand if debt and interest outstrip growth: the spirit may be willing, but the wallet is weak.

As a consequence, the arguments about what is “really” causing the current global slowdown, or the “evolution” of post-industrial economies are constrained by orthodox economists models. In these models, trade is always a win-win, and what causes shifts in the business cycle are changes in technology or tastes. The role of finance – upon which all businesses depend, and of money, on which all purchases depend, has vanished.

Instead, blame and credit is usually focused on the fiscal policies of elected governments in the late 1970s and early 1980s: Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US, while in Canada, Liberal Pierre Trudeau is blamed for the economic woes of the early 1980s, especially the effects of an infamous ‘National Energy Program’ on oil-producing areas.

This is not to deny that Reaganomics, Thatcher’s policies or the Liberal Government’s policies played no role, but the divergence in incomes started in all those countries before Thatcher was elected in 1979 or Reagan was elected in 1980 - usually around 1978, when there were centre-left governments in Canada (Liberal), the US (Democrat) and UK (Labour) – and each of those countries had started pursuing monetarist anti-inflation policies. In 1977, the U.S. Congress amended the Federal Reserve Act to include keeping inflation low (Chicago Federal Reserve 2016), and the

Labour government in the UK implemented deflationary policies (BBC 2014).

Figure 3. Share of Total Income going to the Top 1%. Credit: Max Roser.

The argument for switching to monetarism was that Keynesian economics had never predicted stagflation - rising inflation paired with unemployment and stagnant wages. As Steve Keen argues, this is based in part is based on a double error: not only did critics misinterpret and oversimplify the Philips curve, they exaggerated the extent to which it was an integral part of Keynes’ theories (Keen, 2011, pp. 200-202)

It should be obvious that the inflation and unemployment of the 1970s was caused by the energy crisis and not by rising demands from labour, when the Oil Producing and Exporting Countries (OPEC) used their power as a cartel to turn off the taps to the west. In 1973, the price of oil tripled overnight, and by the Iranian revolution of 1979, it had quadrupled again.

Production in industrial economies depends on the combination of labour, capital machinery and energy to do work. In a 2013 paper, economist James D. Hamilton found not only that every U.S. recession for over a century was preceded by an oil shock, but that the effects of the shock were far greater than just ‘crowding out’ other purchases: it tended to be an order of magnitude greater (Hamilton 2013, 27), meaning that, for example a $3-million overall increase in oil prices would have a $30-million impact on the economy. In an industrialized economy, energy plays a role beyond that of a mere commodity: it underpins every aspect of the economy – from fertilizer in food and cost of inputs, to production, transportation, sales and overhead energy costs.

The 1979-80 global recession occurred when the price of oil soared related to the Iranian revolution. The U.S. Federal reserve knew that the price of foreign oil was the problem, but it was beyond their control, so they used the tools at their disposal to wrestle inflation to the ground (Bryan 2013). Paul Volcker at the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates, sometimes as high as 21.5%.

The UK and Canada (among other countries) had to hike interest rates as well to prevent their currencies from being crushed. In the midst of this recession, governments - including Pierre Trudeau in Canada and Thatcher and Reagan in the UK and US - were borrowing billions to run deficits at 20% interest, laying a base of public debt at colossal interest rates, as did businesses and individuals. Manufacturing was decimated, especially in the UK, but around the developed world as well. There were global repercussions, including the third world debt crisis.

Hindsight being 20/20, Volcker is seen by some as the greatest Federal Reserve Chair in history for ‘defeating’ inflation. While Volcker may get the credit for fighting inflation, prices also dropped because oil prices kept dropping – the very thing that was out of the Fed’s control – reducing the cost of everything. On the fiscal side, after initially cutting taxes, Reagan introduced the largest tax increases (yes, increases) in U.S. history and increased spending, while Volcker relaxed monetary policy. The size of U.S. government grew much more under Reagan’s first term than it did under Obama’s, which helped drive a recovery that led to his re-election in 1984 (Studebaker 2012). Reagan’s Keynesian big-spending is ignored by both his supporters and his detractors, since it is at odds with his mythic reputation as a hero to conservatives and villain to liberals.

The energy crisis sparked a global paradigm shift in economics, and marked a turning point in the mandate of central banks around the world - away from a goal of full employment, to one of suppressing inflation. However, instead of recognizing the role that the deliberate choices of OPEC, central bankers and monetary policies played in these crises, partisans and pundits today tend to give credit or lay blame on elected politicians instead – perhaps because their parties are still around.

5. Long-term effects of low inflation - more, not less instability?

Consider for a moment the long-term effects of monetary and fiscal policies designed to keep inflation and interest rates low for more than three decades. Ultra-low interest rates mean it’s easy to borrow, but impossible to save; savings accounts and bonds pay nothing. In countries with negative interest rates, you pay for the privilege of lending money to banks or the governments. With no safe harbor in banks or government bonds –people put money into stock markets and real estate instead, which are higher return and higher risk. Easy credit drives up asset prices – especially if almost all new money is created in the form of mortgages.

While it’s easy to take on large debts, low inflation makes it harder to pay back loans - even more so when incomes are stagnant. If it looks as if too many people are getting jobs, and wages might go up, the central bank will intervene to drive up unemployment and ensure stable returns for lenders and owners. Demand in the economy can only grow when people borrow. Labour’s share of the economy shrinks while the financial economy grows, because, as Ari Andricopoulos argues, unbalanced incentives are driving people toward rent-seeking instead of either investment in the “real economy” or labour. (Andricopoulos 2016), and the creation of money in the form of mortgage debt tends to lead to financial crises.

Is this a recipe for ‘financial stability’? No. It is the cause, not the cure, of the ongoing crisis we find ourselves in today. The 2008 financial crisis wasn’t caused by inflation: anti-inflationary central bank policies created the conditions to make it possible. Low interest rates made it possible for homeowners to take out colossal loans, but also meant that safe investments, like U.S. government bonds, had a terrible return. Subprime loans, and mortgage-backed securities and high-risk bonds replaced sound government debt as banks’ collateral, and when the housing market collapsed, so did the global financial system.

As Mark Blyth and others have noted, the explosion in public debt occurred after the banking crisis, as tax revenues plummeted, and governments spent money on unemployment claims, bank bail-outs and sometimes stimulus packages. (Blyth 2015)

Now, eight years out, individuals, governments and banks alike have been trapped by this policy: the world is awash in debt, short on work, and instead of addressing demand through more jobs, higher wages and ‘equitable growth,’ the fiscal approach is austerity and the monetary solution is more debt.

In Central Bank Land it’s always either 1978 or 1923: either oil crisis stagflation or Weimar Germany’s hyperinflation: both events are cast as the result of policies gone wrong - unintended consequences, but this is a misreading of history. Both were deliberate political and economic choices – just as Volcker’s decision to hike interest rates was. It is also sometimes suggested that Germany’s experience with hyperinflation led to the rise of the Nazis. This, too, is wrong. German hyperinflation ended abruptly with the introduction of new currency in November 1924. Germany had the fastest growing economy in the world until 1929 and the Wall Street crash, and Hitler rose to power not after hyperinflation, but after harsh austerity. (Blyth 2015)

An obvious, and critical distinction, is in the nature of debt that a central bank or government is trying to deal with. Hyperinflation tends to be associated with a collapse in the value of a currency when a government owes debts in foreign currency. Publicly creating money in order to reduce private debt owed to banks within an economy would have a totally different effect – because the money would be destroyed as it paid down debt.

In the long run, policies that crush inflation are not good for anyone - not little old ladies on pensions, or the government cutting public services, not people who can’t pay their bills, not businesses whose customers are stretching payments - not even the 0.1%, who may see the value of their portfolios crash when people vote for demagogues, or come charging though the gates with torches and pitchforks. If central banks can play a role making inequality worse, they can certainly play a role in making it better. They have in the past.

6. The Great Compression: the only time inequality ever got better

It is sometimes suggested by those looking to minimize the legacy of FDR, that the Depression was ended not by the New Deal, but by the Second World War. This ignores the specifics of what happened between 1938 and 1945, when a phenomenon known as ‘the Great Compression’ took place (Goldin and Margo 1992). In 1975, Arthur Okun wrote that it was the only time in U.S. history that inequality actually improved:

The relative distribution of family income has changed very little in the past generation. The nation took one big step toward equality during World War II: throughout the post-war period, the top income groups have received a substantially smaller share than they had in the prosperous years of the twenties. Since the late forties, however, the proportion of income for each fifth of the population has inched only a tiny bit further toward equality (Okun 1975, 69).

With a mix of wartime spending, wage and price controls, strategic use of resources and rationing, unemployment went down to 2%; and while inflation went up, wages went up faster (Shell 2010, 24-25). The tool stock of the entire country doubled - all of it paid for by government (Gordon 2016). By 1945, the average American worker saved 21% of their income (Shell 2010). Thus, the middle class was created.

Furthermore, 50% of the U.S. war effort was paid for through new taxes, 35% through bonds that were repaid and 15% through Federal Reserve Bond purchases (Institute for New Economic Thinking 2016). This era, from 1945 to 1975, was the so-called ‘golden age of capitalism’, with impressive growth among developed and developing countries alike: inequality did not get appreciably better, but the high growth of that period was more equally shared, so a rising tide lifted all boats.

7. The Bank of Canada

The Great Compression and the New Deal showed that it was possible to end depressions caused by financial crises with fiscal and monetary intervention. While fiscal measures are well known and recognized, the role of central banks in supporting those measures are not. The difficulty is that it took the threat of Depression and the existential threat of global war to force governments to action.

The Bank of Canada was created in 1935 to help Canada deal with the Depression, whose impact on Canada was second only to the U.S. The Bank of Canada still has the power to provide interest-free loans to Canadian governments, or to inject money into the economy via monetized government deficits. The Bank of Canada did this not just during the Depression and the Second World War, but until 1975.

Unlike the European Central Bank, which is barred by the Maastricht Treaty from providing monetary assistance to governments, the obstacle to the Bank of Canada resuming this practice is ideological – it was ended at a time when concern about inflation and stagflation were growing.

In a paper examining the Bank’s role in the Canadian economy from 1935-1975, Josh Ryan-Collins found:

little empirical evidence to support the standard objection to such policies: that they will lead to uncontrollable inflation. Theoretical models of inflationary monetary financing rest upon inaccurate conceptions of the modern endogenous money creation process…during the period 1935–75… working with the government, [the Bank of Canada] engaged in significant direct or indirect monetary financing to support fiscal expansion, economic growth, and industrialization (Ryan-Collins 2015).

Ryan-Collins notes that the establishment of central banks in former British Colonies was different than the origin and purpose of central banks elsewhere – it was done to ‘establish monetary sovereignty from Great Britain,’ and not as a lender of last resort or to fund military ventures. Between 1935 and 1939, the Bank funded:

over two-thirds of government expenditure…Nominal gross national product (GNP) expanded by 77% in contrast to the 70% contraction in the previous five years, with a sharp increase in capital investment and private expenditure… Between 20–25% of Canadian public debt was financed and held by the central bank and government from the end of World War II up to the early 1980s.

The policy of central bank financing of debt was abandoned in the mid-1970s. As Ryan-Collin mentions, this means that in the 1980s, the Canadian government was running high deficits at 20% interest, with the benefits of interest flowing out to private bondholders, instead of back to government. In 1994, the Canadian government embarked on a major austerity program when the Canadian government was facing default due to a lack of interest from the bond markets. The austerity was driven in part by not wanting to turn to the IMF, which would certainly demand draconian cuts.

On the question of inflation, Ryan-Collins’ empirical study finds no correlation between Canadian inflation and monetary injections into the economy – rather, inflation tends to be correlated to U.S. inflation. This is arguably a reflection not only of the role trade with the U.S. plays with Canada, but the role of money creation and destruction in the economy.

8. Cancelling out: public money creation and private money destruction

It is worth considering the mechanism of why money created by central banks might result in growth without significant inflation. The common assumption that injecting money into an economy will necessarily result in inflation is based on a model that treats injections of money as if it is gas into a sealed pressure chamber, with the higher pressure being the equivalent of higher prices.

While this is an inexact analogy, the model changes when we consider the role of money and debt: money is created through lending, and destroyed through repayment.

If a central bank were to provide debt relief by buying up people’s debts and cancelling them, or by requiring lenders to take a haircut or a loss, it would reduce the amount of money and make deflation bearable. The individual is freed of the burden of debt while the creditor gets paid, but since the money leaves the economy, it can play no role in creating inflation.

However, to continue the analogy of the neoclassical pressure chamber – if printing money necessarily causes inflation, there are two other implications. One is that if we take money out of the system, it will cause deflation, because the entire assumption is that the economy is fixed.

This is a relic of the gold and silver standard, and was wrong even then – that the entire value of the overall economy is to be reconciled to a country’s holdings of precious metals. So, what happens when money is fixed, but new value is being created every day: through work, the creation of new tangible assets, and innovation? The creation of real value will grow whether the treasury adds to its gold reserves or not; but that value can only be realized when it is exchanged for money. In such a situation, how can a growing economy create new value if no new money is created? It seems the creation of new money is therefore necessary to reconcile with the creation of new value, even if it just to keep pace with growth.

8.1 Private vs public money creation: distribution and risk

There is also a significant difference in whether that money is created by private banks as loans with interest, or by central banks as money that finances transfers or income from work – money without interest that doesn’t have to be repaid.

The money created by private banks must be repaid with interest – which essentially places a drag on it, reducing its effectiveness in the economy. To drive economic growth, loaned money must generate economic activity that exceeds its interest. At certain levels of debt, interest and low inflation, this will be impossible. In Canada, at the time of writing, household debt has just exceeded 100% of GDP and over 170% of annual income (Quinn 2016).

In contrast, central banks have the power to create money that is ‘irredeemable’ – it is valuable to the person who possesses it, but no one else has a claim on it. If interest free, it may also seem like ‘free money’ – but both ‘free money’ and ‘irredeemable’ may sound like confusing terms. I will instead suggest the term ‘untethered’, for interest-free money without strings – including wages, savings and transfers.

One critical difference between “tethered” and “untethered” money is that that income and wealth distribution have a direct impact on its value. There is an important difference for an individual who receives and spends untethered income generated through work as opposed to tethered money they receive as a loan – and not just that it must be repaid. People who are high risk will face a larger interest rate and costs. With money created as loans, the interest rate is a function of the risk premium or (perceived) risk of default. A rich customer gets low interest rates, a poor customer gets high ones. This is not just universally understood; it is so accepted that no alternative seems possible. The self-evident consequence of such a policy is that it makes inequality a self-fulfilling prophecy: it is a virtuous circle for the wealthy and a vicious one for the poor.

A wealthy borrower can borrow more and invest it, and their low interest rates will make default less likely, but the poor borrower’s higher interest will make failure more likely. What’s more, the rich tend to be creditors, while everyone else are debtors: the result is not just an engine of inequality, but a transfer of wealth from poor to rich.

The injection of central bank-created funds into the economy arguably has the effect not just of increasing economic activity or reducing debt, but, whether it is in the form of a helicopter drop or monetized deficits to create work increases the amount of untethered money in the economy, which because it need not be repaid and has no interest, can flow more freely and is more efficient.

8.2 Discrete private debt vs. unitary public debt

Skeptics will naturally ask, ‘Why should governments take on public debt, or create money, instead of the private sector?’ The presumption and the argument is very often that the wisdom of crowds and the market will do a better job of allocating funds than the decisions of a few policymakers or ‘bureaucrats’.

There are several ways in which private and public debt are very different, most notably in the way they distribute and cope with risk. Government is by its nature unitary, which makes government debt lower risk: it is a single borrower with responsibility for payment diffused among the entire population, at a single rate of interest – usually low.[4] This relationship, of one borrower to many re-payers, makes default less likely – especially if it is a national government backed by a central bank with the authority to create money. Of course, so long as the debt is denominated in the country’s currency, the chance of default is zero.

With private debt issued by banks, the situation is reversed: the private debt market is discrete and divided, with one lender to many borrowers, each solely responsible for repayment, borrowing at different rates of interest, almost always higher than public debt and sometimes at or beyond the limits of usury. Because of the concentration of wealth and income discussed above, a relatively small proportion of the population will qualify for extremely favorable terms, while the terms will be worse for the clear majority. The result, of course, is that as debt grows, increasing amounts will be spent on interest, and as inequality grows, savings will become excessive[5].

This distinction between a unitary government and a discrete private sector is a critical one, and it is widely ignored or overlooked, thanks in part to the economic treatment of ‘aggregates’.

It means that government will draw on and absorb the losses and gains of the entire economy. In contrast, the impact of the downside risks tend to be highly concentrated – sometimes literally limited to individuals. This story changes when debts reach a critical mass and the crisis can travel and amplify, either because barriers to risk transmission have been dismantled through deregulation, or because new pathways to the transmission have risk have been created by more open markets or hedging strategies (like swaps or inadequate or fraudulent insurance schemes) that end up amplifying and spreading risk instead of containing it.

The success and efficiency of the private sector is based in part on looking only at one side of the ledger – successful companies – while ignoring failures, though they are continuous and common. Thousands of individuals and businesses declare bankruptcy every year; 50% of small businesses fail after five years and trillions in wealth were destroyed by the dot.com crash and the 2008 financial crisis. With this blind spot, economics seems to have fallen prey to a similar phenomenon experienced by other sciences of only publishing positive results while ignoring negative or neutral ones.

This difference in interest rates for privately created money and debt vs. public debt has real consequences for the economy. As Andricopoulos writes:

A 10% of GDP increase in private sector debt corresponds to a 0:16% reduction in GDP for every year going forward. Government debt, which would also have a higher positive multiplier when taken out, has less of a negative impact in the future. A 10% of GDP increase in government debt corresponds to just a 0:07% reduction in future GDP growth. The purpose of the DBCF model is to propose a mechanism that would explain this phenomenon. The lower cost of government debt would almost certainly be related to the lower real interest rate paid.

This suggests that government debt is vastly more efficient at stimulating demand than private sector debt. Using an assumption of ∝ on government debt of 0.8% to real GDP (as opposed to NGDP), makes government debt 18 times as efficient in terms of future cost for the same level of stimulus’ (Andricopoulos 2016, 18).

9. Conclusion

Joseph Stiglitz has long been saying that the 2008 financial crisis marked not just a market failure, but the failure of an economic paradigm. In September 2016, Paul Romer essentially denounced three decades of macroeconomics (Romer 2016).

As the world struggles with what Larry Summers has called ‘secular stagnation,’ and governments and central banks around the world struggle to create policies to jumpstart a stalled economy, they are hampered by a neoclassical ideology that not only failed to either predict or explain the crisis, but caused it, and continues to throw up roadblocks and objections to effective ways to address it. In our thinking, we have effectively reverted to pre-Keynesian days.

The trap we are in both ideological and political. While there is no new widely agreed upon paradigm, there is no shortage of theory and evidence from history that demonstrates that central banks not only can, but did play a role in reducing inequality and growing the economy, both in Canada and the U.S. Ryan-Collins’ study of Canada’s experience provides empirical and historic evidence that a central bank can intervene in the economy, supporting both government and private investment, without significant inflation. Andricopoulos has argued the case for monetized deficits to bring down private debt. In 2014, William H. Buiter argued that ‘there always exists– even in a permanent liquidity trap – a combined monetary and fiscal policy action that boosts private demand – in principle without limit. Deflation, “lowflation” and secular stagnation are therefore unnecessary. They are policy choices’ (Buiter 2014).

The situation we are, in other words, is a choice, and central banks’ intervention to reduce private debt is the most positive and least painful, especially when compared to the options of failed austerity. It is a policy option that should be taken seriously, not just because it has been tested and proven to be effective, but because, as Andricopoulos argues, current policies are leading us into a trap where raising interest rates could trigger a debt crisis: ‘Simulating hitting a debt limit also showed the danger of continuing to rely on expansion of private sector debt. For this reason, keeping interest rates low, or even making them negative, is a dangerous and short-term measure. The answer must be fiscal.’

Should a financial crisis befall Canada or another country, monetary financing of government deficits, combined with bank reforms, provides a way to bring the economy back to balance. It may well be worth running a “high-pressure economy” as mentioned by Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen in 2016, and further articulated by Josh Bivens (Bivens 2017). Such an endeavour means restoring demand, and pushing for which in turn would boost capital investment and productivity, and could pay for major infrastructure and other projects that could ease countries’ transitions away from reliance on carbon energy.

The 2008 financial crisis is now being followed by a series of political crises, as governments have not only failed to extricate themselves from the mess, but are in denial about its causes. Voters are rejecting centrist elites and turning to fringe political parties and candidates not just in a mix of hope and desperation, but because they can exact political revenge either on scapegoats or the elites who have prospered while they have suffered.

Rather than recognize the real and damaging effects of long-standing economic policies, elites have tended to dismiss such ‘populism’ as irrational. The limit of their self-examination has been to blame themselves for not adequately selling the real benefits of policies like austerity or free trade to people who lost their jobs, homes, pensions and have seen their incomes stall or sink, while politicians of all stripes insisted on cutting their social programs.

It should be self-evident that when governments and central banks enact policies aimed at protecting or increasing the wealth of the wealthiest - while suppressing wages, employment and even economic growth in order to do so - that it will lead to negative economic and political outcomes. Clearly presented alternatives to improve the situation – like running a high-pressure economy – are often rejected or ignored because they do not conform to a failed status quo, even when supported by theory and evidence.

The current global economic situation makes it clear that these policies – to increase the wealth of the wealthiest - have been a spectacular success, but that they are also generating serious political unrest that could trigger economic downturns, and there has been an astonishing environmental cost. While the EU has effectively outlawed Keynesian economics, (and others have tried), in Canada, the U.S., the UK and elsewhere, central banks have the tools to fund not just a New New Deal, but a New Great Compression - it worked before. It may take an intellectual revolution for the better among central bankers to resolve this situation, but intellectual revolutions are always preferable to the alternative.

Addendum – Sept 20, 2022.

I made very few changes to this paper from when it was presented at the Cross Border Post-Keynesian conference in Buffalo New York in June 2017.

The one important change is a reference to the hyperinflation that took place in Weimar Germany, which – of people who ever talk about hyperinflation - is probably one of the best known such examples.

However, the oft-repeated facts and lessons of that period of history are almost all completely wrong – quite dangerously so. This is from my unpublished manuscript.

“People know that there was a period of hyperinflation in Germany when the value of money dropped so badly that people were wheeling money around in wheelbarrows or used it as wallpaper (all true). This happened in the early 1920s. They also know that after this period, Hitler and the Nazis came to power. People make the mistaken conclusion that hyperinflation led to the rise of fascism and the Second World War.

This is totally inaccurate history and is sometimes used as a reason to warn of the dangers of inflation (Keynes also warned of the dangers of inflation in his “Economic Consequences of the Peace”).

This matters for many reasons, and the real story is worth repeating, to get the order of events straight.

In the 1920s, Germany was faced with massive debts to France and Germany, to pay war reparations.

“According to French and British wishes, Germany was subjected to strict punitive measures under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. The new German government was required to surrender approximately 10 percent of its prewar territory in Europe and all of its overseas possessions. The harbor city of Danzig (now Gdansk) and the coal-rich Saarland were placed under the administration of the League of Nations, and France was allowed to exploit the economic resources of the Saarland until 1935. The German Army and Navy were limited in size. Kaiser Wilhelm II and a number of other high-ranking German officials were to be tried as war criminals. Under the terms of Article 231 of the treaty, the Germans accepted responsibility for the war and, as such, were liable to pay financial reparations to the Allies, though the actual amount would be determined by an Inter-Allied Commission that would present its findings in 1921 (the amount they determined was 132 billion gold Reichsmarks, or $32 billion, which came on top of an initial $5 billion payment demanded by the treaty).”

The hyperinflation in Germany is one of the best known such episodes in history. To give an indication of the level of inflation, a loaf of bread that cost 160 marks at the end of 1922 cost 200,000,000,000 (200 billion) marks a year later.

Many economists, historians and news articles will seek to explain the dangers of hyperinflation by citing Germany, but the history is almost entirely wrong. The Nazis did not come to power until more than half a decade after the hyperinflation had come to an end. The explosion in money-printing in Germany in 1922 and 1923 was not by the government at all.

A clearer story had been produced in a working paper of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[6] It was, in fact, a consequence of a policy blunder by the Allies, who insisted that the government be stripped of its role in supervising or running the central bank:

“The Reichsbank president at the time, Hjalmar Schacht, put the record straight on the real causes of that episode in Schacht (1967). Specifically, in May 1922 the Allies insisted on granting total private control over the Reichsbank. This private institution then allowed private banks to issue massive amounts of currency, until half the money in circulation was private bank money that the Reichsbank readily exchanged for Reichsmarks on demand. The private Reichsbank also enabled speculators to short-sell the currency, which was already under severe pressure due to the transfer problem of the reparations payments pointed out by Keynes (1929). It did so by granting lavish Reichsmark loans to speculators on demand, which they could exchange for foreign currency when forward sales of Reichsmarks matured. When Schacht was appointed, in late 1923, he stopped converting private monies to Reichsmark on demand, he stopped granting Reichsmark loans on demand, and furthermore he made the new Rentenmark non-convertible against foreign currencies. The result was that speculators were crushed and the hyperinflation was stopped. Further support for the currency came from the Dawes plan that significantly reduced unrealistically high reparations payments…. this episode can therefore clearly not be blamed on excessive money printing by a government-run central bank, but rather on a combination of excessive reparations claims and of massive money creation by private speculators, aided and abetted by a private central bank.”

So, it was not the German government that was responsible for hyperinflation at all. It was the private central bank, which allowed private banks to print their own currency – to offer credit that was convertible into government marks on demand. Effectively, it gave private banks a license to print money, and they did.

Bibliography

Andricopoulos, Ari D. 2016. "The Relationship Between High Debt Levels and Economic Stagnation, Explained by a Simple Cash Flow Model of the Economy." Social Science Research Network (SSRN) 41.

Bank of England. 2014. "Money Creation in the Modern Economy." Bank of England. March 14. Accessed November 23, 2016. http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf.

BBC. 2014. James Callaghan (1912 - 2005). March 15. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/callaghan_james.shtml.

Blyth, Mark. 2015. Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Bryan, Michael. 2013. "The Great Inflation." Federal Reserve History. November 22. Accessed November 14, 2016. http://www.federalreservehistory.org/Events/DetailView/64.

Buiter, William H. 2014. "The Simple Analytics of Helicopter Money: Why It Works – Always." Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal 8: 1.

Chang, Ha-Joon. 2008. Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism. Paperback, 2009. New York, New York: Bloomsbury Press.

—. 2014. Economics: The User's Guide. Paperback Edition 2015. New York, New York: Bloomsbury Press .

Chicago Federal Reserve. 2016. The Federal Reserve's Dual Mandate. November 07. Accessed December 15, 2016. https://www.chicagofed.org/publications/speeches/our-dual-mandate.

Domhoff, G William. 2013. Wealth, Income, and Power. February 1. Accessed December 20, 2016. http://www2.ucsc.edu/whorulesamerica/power/wealth.html.

Frankel, Jeffrey. 2016. Lower interest rates are not the demon of populist claims. October 25. Accessed November 16, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/business/economics-blog/2016/oct/25/lower-interest-rates-not-demon-populist-claims-inequality-government.

Goldin, Claudia, and Robert A. Margo. 1992. "The Great Compression: The Wage Structure in the United States at Mid-Century." The Quarterly Journal of Economics (The MIT Press) 107 (1): 1-34.

Gordon, Phillips. 2016. "After 150 years, the American productivity miracle is over." Quartz. March 9. Accessed November 4, 2016. http://qz.com/633080/the-rise-and-fall-of-american-productivity-growth.

Hamilton, James. D. 2013. "Historical Oil Shocks." Edited by Randall E. Parker and Robert Whaples. Routledge Handbook of Major Events in Economic History (Routledge Taylor and Francis Group) 239-265.

Hudson, Richard, and Benoit Mandebrot. 2004. The (mis) Behaviour of Markets: A Fractal View of Risk, Ruin and Reward. Paperback, 2006. New York, New York: Basic Books.

Institute for New Economic Thinking. 2016. Finance & Society: Secular Stagnation: Out of Ammunition? A discussion on central banking and secular stagnation with Larry Summers and Adair Turner. October 7. Accessed November 17, 2016. https://www.ineteconomics.org/events/finance-society-secular-stagnation.

Keen, Steve. 2011. Debunking Economics. London: Zed Books.

—. 2012. "The Debtwatch Manifesto." Steve Keen's Debtwatch. January 1. Accessed November 28, 2016. https://keenomics.s3.amazonaws.com/debtdeflation_media/2012/01/TheDebtwatchManifesto.pdf.

Mackenzie, Hugh. 2016. Staying Power: CEO Pay in Canada. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Toronto: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 9.

Okun, Arthur. 1975. Equality and efficiency, the big trade-off. Brookings Institution Press.

Oxfam. 2016. "An Economy for the 1%: How privilege and power in the economy drive extreme inequality and how this can be stopped." Oxfam America. January 18. Accessed November 4, 2016. https://www.oxfamamerica.org/static/media/files/bp210-economy-one-percent-tax-havens-180116-en_0.pdf.

Quinn, Greg. 2016. Bloomberg Markets. December 14. Accessed December 15, 2016. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-12-14/canada-household-debt-ratio-hits-record-with-c-2-trillion-tab.

Romer, Paul. 2016. "The Problem with Macroeconomics." Harvard Business Review.

Ryan-Collins, Josh. 2015. "Is Monetary Financing Inflationary? A Case Study of the Canadian Economy, 1935–75." Working Paper, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson.

Shell, Ellen Ruppel. 2010. Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture. New York, New York: Penguin.

Smith, Adam. 1776. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. 5th. New York: Bantam Classic.

Statistics Canada . 2013. Individuals by total income level, by province and territory (Canada). Statistics Canada , Government of Canada, Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada. 2013. Survey of Financial Security 2013. Statistics Canada, Government of Canada, Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Stiglitz, Joseph. 2012. The Price of Inequality. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Studebaker, Benjamin. 2012. Stagflation: What Really Happened in the 70’s. December 30. Accessed November 14, 2016. https://benjaminstudebaker.com/2012/12/30/stagflation-what-really-happened-in-the-70s/.

Williams, Sean. 2016. Nearly 7 in 10 Americans Have Less Than $1,000 in Savings, New Study Shows. Sept 25. Accessed December 17, 2016. http://www.fool.com/retirement/2016/09/25/nearly-7-in-10-americans-have-less-than-1000-in-sa.aspx.

[1] More recent research shows that Weimar Republic Hyperinflation was caused due to the privatization of the central bank and the decision to honour all banknotes as currency, effectively creating private banking printing presses. When the currency was replaced, hyperinflation ceased.

[2] Buiter says three conditions must be satisfied: ‘First, there must be benefits from holding fiat base money other than its pecuniary rate of return. Second, fiat base money is irredeemable – viewed as an asset by the holder but not as a liability by the issuer. Third, the price of money is positive. Given these three conditions, there always exists – even in a permanent liquidity trap – a combined monetary and fiscal policy action that boosts private demand – in principle without limit.’

[3] People whose losses could easily be made up through redistribution in a welfare state

[4] This is quite aside from the other ways in which governments could pay off debt, by selling assets, or in the case of federal governments with central banks and their own currency, the ability to print money for the purpose of debt repayment.

[5] It is worth noting that modern banks have also created modified consumer debt products, like lines of credit, based on the model of the credit card. Unlike mortgages, which face default if payments are missed, lines of credit are designed not to require being paid down. While this avoids default, it allows for interest-only payments, which are profit for the bank, while debt is never paid down at all.

[6] https://canadiandimension.com/articles/view/whatever-happened-to-the-saskatchewan-ndp

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12202.pdf

Superb!!! In some ways it anticipated where we are now!

I know Steve Keen thinks highly of your work and the quality of your writing!