Chapter 4. The Roaring 1920s: the KKK brings its terror to Canada

In 1928, the May Long Weekend in Saskatchewan and Manitoba was marked by cross burnings in over 150 communities.

The world was emerging from the First World War, and a global pandemic. Europe was still in chaos, and economic growth was uneven. There were growing social tensions and insecurity for everyone else, resulting in extremism, hate groups and nativism.

Across Canada in the 1920s, there were firebombings, death threats and cross burnings. There were attacks on Catholic Churches in Quebec City. A stick of dynamite blew a hole in a Catholic church in Barrie, Ontario. In 1922, St. Boniface College in Manitoba burned, killing ten students. Marjorie Treichel’s 1974 Master’s Thesis sets at the University of Manitoba

“The anti-Catholic stance of the Ku Klux Klan, only one of its many themes in the U.S.A. where Catholics were a definite minority, was to take on outsized proportions in Canada where French Roman Catholic - English Protestant relations were a particularly sensitive issue. In hopes of gaining the favour of ultra-Protestant extremists, this is where the Klan first struck.

In late 1922 fire destroyed an estimated $ 7,000,000 or more worth of Roman Catholic Church property. Fires at such places as St. Anne de Beaupre, the University of Montreal, St. Boniface College,. and the Quebec Basilica were blamed on the Klan. Evidence was wanting, but not indications. Notices such as that received by St. Michael's Roman Catholic Church and the headquarters of the Knights of Columbus at St. Lambert, Quebec, threatening their destruction by the "K.K.K." did nothing to alleviate suspicion.

And then one morning, in June, 1926, the citizens of Barrie, Ontario awoke to the startling news that Klansmen had tried to dynamite their local St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church at the midnight hour. The Klansmen were no more successful in that than in removing all incriminating evidence. Three Klan culprits were speedily brought to trial and all the interesting details of their misadventures given a thorough airing in court and news headlines. It was the first case of irrefutable evidence of Klan designs to destroy Catholic property. The church was repaired, the dynamiter sent to Kingston penitentiary for five years after which he was to be deported to Ireland, and the Barrie Klan Cyclops and Secretary given four and three year terms respectively at Kingston.”

From 1927 to 1929, membership in the KKK in Saskatchewan soared to 25,000 members, with chapters in every major city. They were campaigning against liquor and crime, Saskatchewan’s First Nations, and Catholics - including Ukrainian and Polish Immigrants, but especially French Catholics.

In 1928, the Klan expanded into Manitoba. Winnipeg at the time was the third largest city in Canada, and had significant Jewish as well as French, Ukrainian and Polish Catholic Communities.

The major organizer for Manitoba was “Daniel Carlyle Grant, the Moose Jaw-based Klan Kleagle, now calling himself the “Organizer for the Western Division of the Ku Klux Klan of Canada.” Grant, a shrewd and capable organizer with ““the instincts of a shark,” knew how to attract attention.”

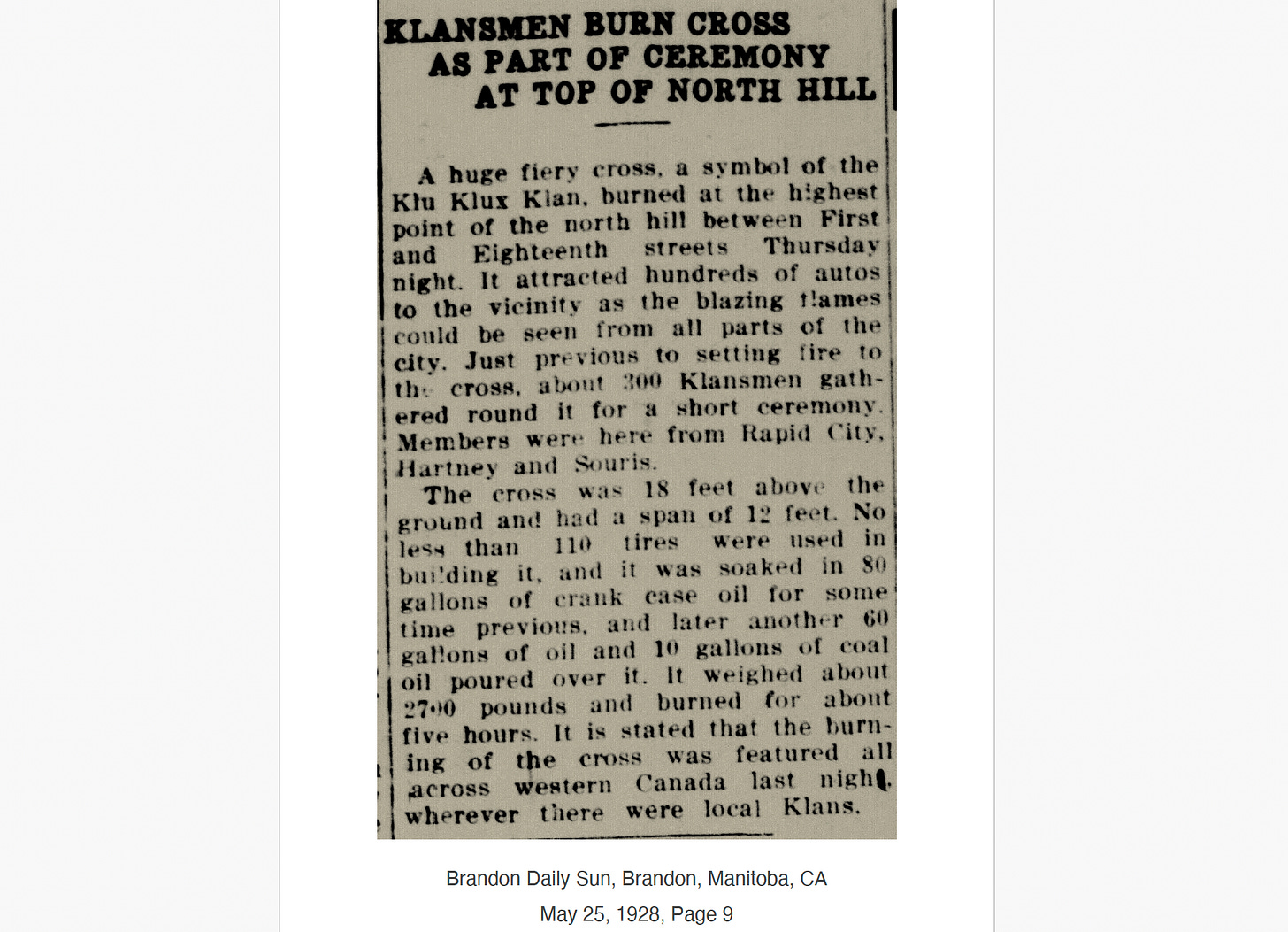

Grant was based out of Brandon, and like other KKK organizers was getting from place to place by rail. On May 25, 1928, the Brandon Sun reported that a giant cross had been burned on the north hill of the city.

“The cross was 18 feet above the ground and had a span of 12 feet. No less than 110 tires were used in building it, and it was soaked in 80 gallons of crank case oil for some time previous, and later another 60 gallons of oil and 10 gallons of coal oil. It weighed about 2700 pounds and burned for about five hours.”

It was one of more than 150 KKK cross burnings that took place across the prairies in the late 1920s, especially on the “Empire Day” long weekend in May, now renamed Victoria Day.

“On Empire Day (24 May 1928) a cross was burned just outside the Kerrobert town limits.” That same night, crosses were burned in communities all across Saskatchewan. One of the largest gatherings was near Melfort, where the crowd was estimated at between seven and eight thousand people. Over twelve hundred automobiles were parked around the platform.

Klan organizer R.C. Snelgrove gave an address, which garnered much applause. He said that Klan demonstrations were being held that day at 161 different locations in Saskatchewan, including Regina, where, he said, a crowd of between thirty and forty thousand people was expected to attend the cross burning. (According to press reports, the number was only fifteen hundred. The cross was twenty-four metres high, and a steam tractor was required to elevate it.)”

Snelgrove had defected from the Saskatchewan Liberals, whose Leader, Jimmy Gardiner, bitterly opposed.

As a KKK organizer, Grant had had some success in Manitoba – about 2,000 members, which was nothing like the 25,000 Klan members in Saskatchewan. At meetings, he used racist epithets for Blacks, Asians, Jews, and Catholics.

The Manitoba Historical Society’s website has an entire page dedicated to Grant’s efforts to organize the Klan in Manitoba. Grant had his first meeting in Winnipeg just a few days after the long weekend cross-burning in Brandon, on June 1, 1928, at the Royal Templars’ Hall at 360 Young Street.

“In this meeting, his attack on Roman Catholics and Jews set the pattern for his future Winnipeg campaign. In his speech, Grant informed his audience that the Roman Catholic Church controlled the Dominion and that the Jews had crucified the Son of God. Shortly after this meeting, Grant returned to Saskatchewan believing that the Klan could take hold in Winnipeg.

By autumn 1928, Grant was back in Manitoba once again, basing himself in Brandon. Grant, now calling himself the Manitoba Organizer of the Invisible Empire Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, plotted the Klan invasion of Winnipeg. In October, Grant shifted his activities to Winnipeg and set himself up at the Marlborough Hotel on Smith Street just north of Portage Avenue. He was joined by Charles H. Puckering and Andrew Wright, a local Klansman. The trio soon made their plans of action for their Winnipeg campaign.”

On October 16, 1928, at the Norman Dance Hall on Sherbrook in Winnipeg, Grant told an audience of 150 that:

“The Klan strove for “racial purity. We fight against intermarrying of Negroes and whites, Japs and White, Chinese and Whites. This intermarriage is a menace to the world. If I am walking down the street and a Negro doesn’t give me half the sidewalk, I know what to do.” He then lashed out at the Jews and said that “The Jews are too powerful ... they are the slave masters who are throttling the throats of white persons to enrich themselves.” Grant claimed that the federal Liberal government was allowing the “scum of Papist Europe to flood the country and refuse to allow immigrants into the country who are not Roman Catholic ...”

Grant said he was going to go to St. Boniface, the city’s largely Catholic French quarter next.

“Reaction to Grant’s statements came immediately. The Priest in charge of St. Boniface Cathedral, Monseigneur Wilfred Jubinville, accused Grant of being a coward, and warned him to stay out of St. Boniface. The priest stated that the Roman Catholic Church would fight the Klan to the full extent of its power. Monseigneur Jubinville summed up the Klan’s activities in Winnipeg as a “scheme to raise a little ‘easy money’.”

St. Boniface police chief Thomas Gagnon stated that, “There is nothing in St. Boniface to attract the Klan,” and furthermore, he denied that the city “was held in a grip of vice.” Police chief Gagnon went on to say that if the Klan “raided” St. Boniface, drastic police action would be taken.”

Winnipeg mayor Daniel McLean, a businessman and distinguished soldier who was Colonel-in-command of the Canadian 101st Battalion in France, 1916–1918, dismissed all the Klan’s charges and noted that “when outsiders come into Winnipeg and criticize as these people have done, we simply pay no attention to their remarks.”

After a rough go of it in Winnipeg, Grant ended up returning to Saskatchewan, where he was an organizer and sometime driver and bodyguard for J. J. Maloney, a Catholic-turned-Klansman who spread hate with all the enthusiasm of a convert.

“Grant withdrew from Manitoba and returned to Saskatchewan where he campaigned for the Klan against Premier James Gardiner and the Liberal Party in the 1929 provincial election.

After the Anderson Conservative Party victory, Grant was given a job in charge of the Weyburn Employment Bureau. Soon after the Liberal Party’s return to power in 1934, Grant was sacked from his job.”

Grant would emerge again to play a pivotal role in the Federal Election campaign of 1935, when he “came into prominence once again as one of Tommy Douglas’ Co-operative Commonwealth Federation campaign workers in the federal election of that year.”[1]

Tommy Douglas was elected to parliament for the first time with the help of Daniel Carlyle Grant, the chief organizer for Western Canada for the Ku Klux Klan.

The KKK in Saskatchewan

The KKK were an extraordinary political force in Saskatchewan in the 1920s. Their membership was estimated at an incredible 25,000 people (though they claimed twice as many). The Ku Klux Klan in Canadaby Allan Bartley, and James M Pitsula’s Keeping Canada British cover the period in question.

The KKK was present across Canada but found particularly fertile ground in Saskatchewan. The common thread was “Orange” Protestantism. “The Orange Order, also known as The Loyal Orange Institution, was founded in 1795, sworn to uphold the ideals of the Protestant Ascendancy.”[2] They were named after William of Orange to commemorate his victory over Irish Catholics in 1690, and it would be polite to suggest they were jingoistic, nationalist, or “protestant chauvinist”. Their bigotry ran deep and was contemptuous of those they opposed, especially Catholics. It helped shape and define hundreds of years of oppression and conflict, from civil wars to the Irish Famine and “The Troubles” between Ireland and Northern Ireland that killed 3,000 people from the late 1960s to the late 1990s.

It is important to recognize the anti-Catholic indoctrination that had already long been part of protestant culture, in the form of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. The book was an epic and graphic 1500-page blow-blow-by account of the persecution of protestants by Catholics, with illustrations. In 1571, a Convocation Order meant that copies of the Book were distributed to Cathedrals and churches, where it was chained to Great Bibles. It helped define the English character and British Protestants’ sense of themselves and is considered one of the most influential books in English history.

It was read alongside the Bible, and unlike the Bible, had illustrations that all could access, including people who couldn’t read. They often depicted real, and lurid events that had happened in Britain, Ireland and Europe, like martyrs being burned alive, which generated hatred for Catholics and sympathy for the dead. This is not to say the incidents in the book were fictional. Many of the horrific incidents did happen – but the presentation was partisan, and crafted for political effect, with considerable success.

This needs to be said, simply because there have always been various branches of Protestantism, but Orangemen were especially numerous in Ontario and played an outsize role in the founding and development of Upper Canada.

It’s been suggested that the Ku Klux Klan did not take serious root in Ontario because the Orange Order was so well established. British protestants were already firmly in charge and in power, so there was no need to supplant them.

In Saskatchewan, however, the Liberals were in charge, and were supported by Catholics. This opened up the province for recruiting possibilities, because they could work together.

“According to Allan Bartley, the Klan did not thrive in Ontario because it was redundant. “The [Orange] Lodge [in Ontario] could afford to tolerate the Klan up to a point,” he writes, but the LOL [Loyal Orange Lodge] clearly had the sales territory sewed up tight.”

“Indeed,” he adds, “what was there in the Klan's political agenda that was not already within the reach of the Tory-Orange axis? In truth, very little.” In Ontario, the Conservative Party, backed by the Orange Lodge, controlled the provincial government. In Saskatchewan, the situation was quite the reverse.The Liberal Party, no friend of the orange order, had been in power since 1905. To get rid of the Gardiner government, Orangemen had to make common cause with the Klan. The organizations were complementary and overlapping, not competitive or mutually exclusive. This helps explain why the Klan succeeded in Saskatchewan while it floundered in Ontario. Ontario Orangemen had no need of the Klan, while those in Saskatchewan had an interest in having the Klan succeed.”

One of the major sources for the story of the Klan in Saskatchewan is derived from the 1968 Master’s thesis of William Calderwood, which drew on the papers of former Liberal Premier Jimmy Gardiner, who kept clippings and lists of Klan members.

From today’s perspective, there was always an uncomfortable overlap in shared values between many “Progressives,” CCF-type social gospellers, and the Ku Klux Klan. They were white, Anglo-Saxon protestants who could agree on multiple fronts: they all supported votes for women, eugenics and forced sterilization, and the prohibition of alcohol. They were all protestant Christians. They all opposed “vice” and the people they considered to be inferior that they blamed for it - Catholics, (whether French, Polish, Ukrainian or other), Jews, immigrants, alcohol - and the only political party they associated with all of those communities, as well as some progressive protestants - Liberals.

James M. Pitsula’s history Keeping Canada British is, at times, quite forgiving of the Klan in Saskatchewan. At one point, Pitsula refers to the Klan in Saskatchewan as “essentially, a lobby group,” and writes that “The Klan played upon existing racial prejudices. It did not create them,” - as if, by actively spreading hate and conspiracy theories they didn’t make things worse.

He suggests that Gardiner’s attacks on the Klan weren’t grounded because he couldn’t get convictions of the Klan in court - as if the Klan was not known for influencing jury trials! He even complains that in Gardiner’s attacks on the Klan, he didn’t give them credit for the fact that they were independent from other branches of the KKK.

“It is evident that the Klan was not generally regarded as an outcast group or disreputable organization; rather, it was perceived as just another civic body, entitled, like any other, to use city hall for its meetings. There was no thought, except among Catholics, that the Klan should be ostracized from polite society. Alderman M.J. Coldwell (future leader of the national Co-operative Commonwealth Federation [CCF]) maintained that the hall should be available to any group provided that it respected the “decencies of language and parliamentary procedure.”

Pitsula is engaged in some historic “compartmentalization” – both of Coldwell and of the Klan in Saskatchewan.

Catholics’ fear for their safety as well as their rights were justified. As mentioned above, throughout the 1920s, there had been attacks and threats across Canada. In Saskatchewan,

“The town of Biggar and environs were awash in Orange Lodge rage, Ku Klux Klan recruiting and a tangible sense of threat to the Catholic community. Crosses were burned on the lawns of Catholics across the district that spring and early summer of 1929. The Mother Superior of the sisters of the Assumption confessed her relief when fire escapes were installed on the new Catholic school outside Biggar. “We will now be less afraid of the local fanatics should they take a notion to set fire to our house,” she wrote in her journal.”

It is questionable, in many ways, to lean on M. J. Coldwell’s future credentials as a future leader of the CCF - more than a decade later - to gauge the KKKs respectability in the 1920s. In the 1929 election Coldwell was allied with the Progressive Party, which “threw its support to the Conservatives, which along with that of the independents enabled Anderson to take over the government.”

Pitsula is borrowing credibility from the future CCF in order to lend it to the past – to the benefit of the KKK.

Citing CCF “values” has been a way of expecting readers to take it on faith that the people who spout values of tolerance and equality actually live by them. Lots of people and politicians don’t practice what they preach, and there’s no party that’s any exception. They get publicists. They promote “narratives”.

Coldwell was a veteran “Anti-Liberal” and was aligned with the Progressive Party, which like the UFA and others supported eugenics as a policy. Coldwell ran in the 1927 Federal election for the Progressives, but lost, and ran for Alderman in Regina instead. Not only did he show indifference to the Klan meeting at Regina City Hall, but he also shared their anti-immigrant attitudes.

In 1928, “Coldwell stated that the unemployment situation was very serious in Regina and was being made worse by untrammeled immigration. He maintained the railway companies were making exorbitant profits out of “bringing people from all over Europe.”

Pitsula’s book also cites William Calderwood’s thesis, which discusses connections between the Progressives and the KKK at length:

“In the little that has been written about the Klan in Saskatchewan, the organization is depicted as the Conservative party's friend and the Liberal party 's enemy; almost nothing is written about the Progressives, the official party of opposition in the Legislature. Yet with regard to membership in the Klan, the Progressives probably ran a close second to the Conservatives. The names of some prominent Progressives appear in the Klan membership lists:

Rev. A. J. Lewis, former Progressive M. P., defeated in the 1925 election, Kligrapp of the Strasbourg Klan; Thomas Teare, a charter member of “The New National Policy Political Association,” later the Progressive party, member of the Moose Jaw Klavern; E. Jones, Secretary-Treasurer of Rosetown Progressive party organization, member of the Harris Klavern; J. W. Vandergrift, a member of the executive of the Progressive party for Maple Creek constituency, member of the Pontiex Klavern; John McCloy, a former Progressive candidate and a member of the Board of Directors of the U. F. C. (Saskatchewan Section), member of Kinistino Klavern; J. Balfour, a delegate to the Progressive Convention in January 1926, member of the Balcarres Klavern; and John Evans, another Progressive M. P., addressed a Klan rally at Saskatoon. One can assume that if some Progressive leaders were members of the Klan, then many of the rank and file would follow suit.

As the author of an “Open Letter To Premier Gardiner” observed:

“Sir, you have devoted a lot of time to the Tory party and the Klan. But your speeches contain very little about the Progressive party. I know you think you killed it when you ridiculed the Regina Convention. I am afraid it did not stay dead, and I am told that since then there has been an infusion of new blood by means of the Klan whose vote you said you did not want; other parties may not despise them.”

In the 1929 Saskatchewan Election, Coldwell supported the Progressives, whose platform against the Liberals, and Catholics, was even more like the Klan’s than the Conservatives.

“On the other pet themes of the Klan lecturers - immigration, education, and the influence of the Quebec hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church - the Progressives were in complete agreement. This is best illustrated by the Progressive platform of 1929… When the same planks in each platform are compared … the wording of the Progressive planks were more emotionally tinged than the Conservative.

The Conservative plank on immigration, for example, was “Aggressive immigration policy based on the selective principle”; while the Progressive counterpart was “An Immigration policy which will insure the permanency of British Institutions and Ideals.”

On the education issue, the Conservatives requested a “Thorough revision of the educational system of the province;” the Progressives desired the “Freedom of our public schools from sectarian influence, with increased emphasis on moral training.

The Progressives also shared the Klan's suspicions of Quebec.” (Calderwood, 234-35)

In effect, Pitsula is allowing Coldwell to “play dumb” about not knowing about official Klan involvement either in the Conservative Party, or his own party, the Progressives.

There was a clear overlap between the leaders and followers of the CCF, the KKK, Orangemen, Conservatives, Social Credit, Farmers and labour. They were almost all white British or American protestants, some of whom were religious zealots - who opposed non-British or American immigrants, Catholics, Jews, and Quebec and who all supported eugenics because they believed themselves to be superior. There were also Liberals who were involved, but not at the top.

The phenomenon of the KKK in Saskatchewan is portrayed as a sudden storm that blew up and disappeared, when their ideas were being mainstreamed into government. The odious political views shared by most political parties in Saskatchewan and Alberta in the 1930s are being portrayed as a temporary aberration, when they were held for years or decades and KKK organizers tipped the balance in provincial and individual federal election campaigns in Saskatchewan in 1929, 1930 and 1935.

It's also important to get our history straight: the KKK’s popularity in Saskatchewan happened before the Great Depression. After the market crash of 1929, the soaring price of wheat – the major basis of prosperity in Saskatchewan and Alberta – collapsed. During the Depression, Canada had one of the worst economic collapses of any country in the world, and in Western Canada it was worst of all. There was unemployment of up to 75% in some towns.

“The Great Depression wrought great economic hardship throughout the world, but few places suffered so sharp a decline in income or required so much government assistance to survive as the Canadian prairie provinces. From 1928 to 1932 Canada's agricultural economy declined 68 per cent while the Prairies ' declined 92 per cent. In Alberta the average per capita income in 1928-29 was $548 ; in 1933 it decreased by 61 per cent to$ 212. The Canadian average per capita decrease during the same period was 48 per cent.”

It is no secret that financial crashes and the mania that precedes them radicalize people. The idea that people were driven to extreme politics and beliefs by the Depression has to be challenged – the extremism preceded the crash. Again, the KKK’s involvement in the Saskatchewan 1929 election pre-dated the crash. So did Alberta’s passage of sterilization laws in 1928.

And in 1929, the province of Saskatchewan was due for a general election. And the KKK played a decisive role in the outcome.

[1] http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/85/winnipegkkk.shtml

[2] https://theculturetrip.com/europe/united-kingdom/northern-ireland/articles/who-are-the-orangemen-and-what-is-the-orange-order/