Church and State: A Question in Good Faith for Economically Conservative Christians

Rendering Unto Caesar: The central lessons of Christ's last days appear to be about justice and debt forgiveness, especially for the poor.

Many conservative political parties may have strong connections and support from Christian denominations. In the U.S. and Canada, in particular, as well as in other countries around the world. In the U.S. Republican Party, they were once referred to as “Neocons and Theocons,” with neoconservatives being motivated by economic and military policy, and theoconservatives being “social conservatives”.

For whatever reason, this “social conservatism” is generally separate from the issue of poverty and economics. I find this interesting - especially since I don’t see the far-right economics of many modern conservatives conforming to Christian teachings about poverty.

There is also tradition in some denominations of the “social gospel”.

Ted Cruz, the Canadian-Born Texas Republican Senator who is an Evangelical Christian, had this to day about the “Social Gospel”":

“If we look at it more from a philosophical standpoint, these foundations of atheism and secular humanism believe that you are your own God. That leads us to something that unfortunately has crept into many churches across America, and it is what I call the Social Gospel. The social gospel, that could creep into something that is called Liberation Theology, which is a mixture of leftist, pseudo-Christianity with Marxism.

Cruz is not alone in taking this position - and I don’t understand it, because to me it seems to me to be completely in opposition to some of Christ’s most important teachings.

One of the reasons for the economically or politically liberal Catholics was that there was an economic social justice tradition in the Church, which was a reflection of the teachings of the gospel.

Over the last decade and more I have done extensive reading on economics and economic history. I had spent a number of years working in policy research and platform, and ten years ago I was considering taking a PhD in Economics. I have an M.A. in English Literature, but once you have a graduate degree, you can start a PhD in a different subject.

Politics got in the way, but I kept reading, including the fascinating book, “...and forgive them their debts: Lending, Foreclosure and Redemption From Bronze Age Finance to the Jubilee Year.” by economist and expert in the history of the Babylonian near east Michael Hudson. The read is dense, but it puts a fascinating new historical context around the real events and lessons of the Bible as part of a tradition that was millennia old, and it was named the Financial Times of London’s book of the year when it came out.

I am genuinely interested what people think of this interpretation, and whether it affects their own view of their own economic ideas.

What I would like to do is set out my understanding of the key lessons at the end of Christ’s life, with some additional context around the real history of the period, because I find them fascinating and compelling.

I do want to make it clear and be honest about the fact that : I am not a religious person. Growing up neither my father nor my grandparents were religious and we did not attend Church. Others in my family embraced religion and as a Generation X-er I grew up and attended school with Jews, Sikhs, Muslims and Hindus, as well as Christians.

So I have always wondered, why is there this gap between “theory and practice” is managed - especially as I learned more about Christian lessons in the Bible that appear to be quite clear, but are not taken literally.

In all systems of belief - including secular ideological ones - people can have two kinds of “taboo reactions” - people are shocked and often angry when others don’t share their beliefs, or they think that disagreement is criticism.

I believe that disagreement over belief - or not accepting someone else’s faith - need not be disrespectful. I am trying to operate in “good faith” - “a sincere intention to be fair, open, and honest, regardless of the outcome of the interaction.”

Out of the Wilderness & Proclaiming the Year of Our Lord

When Christ returns from his time in the wilderness, he goes to his synagogue in Nazareth, he stands up and reads from a part of the Torah. Luke 4-16 –to 4:20 reads

“And he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up: and, as his custom was, he went into the synagogue on the sabbath day, and stood up for to read.

And there was delivered unto him the book of the prophet Esaias. And when he had opened the book, he found the place where it was written,

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised,

And he closed the book, and he gave it again to the minister, and sat down. And the eyes of all them that were in the synagogue were fastened on him.”

Jesus shocked the congregation by reading from Esaias (or Isaiah)– and calling for a jubilee year.

This is a return to the ancient law, where every 49 years, there would be a proclamation of debt relief, which provides relief to poor by freeing them from debt bondage, and to return to productive work. It is more than just money - when people couldn’t pay their debts, they would lose their land, or their personal liberty. They might be required to work as slaves, or hand over their family members as collateral, to be released when the debt was repaid.

A Jubilee year was designed to remedy that: not only would the poor be released from their financial debts, they would be released from slavery, and would be able to return to land that would be made available and be able to start working for themselves.

The congregation is stunned and angry, by his audacity – and because he is shaming them. He is challenging them to follow their own rules and live their beliefs. Clearly, they have not been, because otherwise, He would not have to ask.

That’s why he follows with two phrases that have endured for millennia -

“Physician, heal thyself,” because he expects them to take their own medicine, and follow their own rules and practice what they preach. He also realizes why he is getting resistance: “No prophet is accepted in his own country.”

The reaction to Christ’s action is fierce. An angry mob gathers and threatens to throw him off a cliff, but he escapes, and keeps preaching in synagogues, spreading the “Good News” which is proclaiming the Jubilee year. That is the “good news” or gospel that Jesus is spreading - that he is declaring a Year of Our Lord, a Jubilee, according to the ancient laws of the Torah. We get the word “Gospel” or “God Spell” from Norse words for “Good story.” In Norse, “good” is “God” and “spell” means “news” or “story.”

It is very clear that Jesus’ overriding focus is on relief for the poor, and in calling for a debt jubilee. It’s important to understand this additional context. As spelled out in Proverbs 19:17 helping the poor is a way of repaying your debt to God,

“He that hath pity upon the poor lendeth unto the LORD; and that which he hath given will he pay him again.”

Another way of putting it is if you to do the right thing to get to heaven, you need to do a couple of things. If you are wealthy and successful, then God is asking you to be humble enough to admit that He played a bigger role in it than you may be willing to admit, and because God played a role in your success, you owe Him. And you pay Him back by giving relief to the poor.

After leaving his old synagogue behind him, Christ travels to Jerusalem and to the temple.

“And forgive us our debts”

He also delivers the Sermon on the Mount, including the Lord’s Prayer, here there is a key line that has two translations. The line “forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us” is also translated in Matthew 6:12 as “And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.”

A typical explanation for what a “trespass” is that it applies to just about any kind of moral slight - violating a boundary or law.

The discussion here of what the word meant in the original Koine Greek makes it clear that:

“The Greek word is a form of ὀφείλημα (3783), which according to Strong's has been translated

that which is owed 1a) that which is justly or legally due, a debt 2) metaph. offence, sin

The word comes from ὀφείλω (3784):

to owe 1a) to owe money, be in debt for 1a1) that which is due, the debt 2) metaph. the goodwill due

Lexical sources

According to BDAG (and Moulton & Milligan), the primary meaning of ὀφείλημα is

that which is owed in a financial sense, debt, one’s due.1

It can also refer to an "obligation in a moral sense, debt" (and is used in a similar way to the Aramaic חוֹבָא in rabbinical literature).2”

Translators then go on to argue that it likely means “sin” but this may be begging the question. The other examples of the word’s use in the Bible include money-debt forgiveness.

Invoking Isaiah and the Gospel in the Parable of the Sower

The Parable of the Sower has several different accounts in the Bible, in the books of Matthew, Mark and Luke. It includes a reference that can be understood to be describing the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer:

Matthew 13:12 in the King James Version reads

For whosoever hath, to him shall be given, and he shall have more abundance: but whosoever hath not, from him shall be taken away even that he hath.

Jesus is describing what happens when debts are allowed to keep building up - the rich get richer and the poor keep getting poorer. He follows up immediately by saying he is speaking in parables to share with the crowd what his disciples already know.

14 In them the prophecy of Isaiah is fulfilled:

The entire chapter of Matthew 13 takes on a different meaning if it is understood to be Jesus preaching the prophecy of Isaiah, and if the “gospel” or good news is that a jubilee year is to be enacted.

Jesus is telling parables about debt - about real value and waste. He makes the real point that for farmer, not all seeds will grow, and for the fisher that not all fish are worth keeping. These are real life losses - and the debt is like weeds, or catch that’s discarded, or that a tiny mustard seed will grow into a tree.

He’s talking about how the Good News of declaring a Jubilee - will lead to new growth and prosperity for all. The Kingdom of Heaven and the declaring year of the lord is achieved by fulfilling the prophecy of Isaiah.

The example He gives is of a farmer who has weeds in his field, but pulling them up will ruin his crop. So at the end of it, they will gather the wheat and weeds separately, and burn the weeds. The theme, over and over, is gathering and preserving real value, and casting aside waste - and of convincing people that they will be liberated by a Jubilee.

And there is an important mistranslation which refers to “the end of the world” which in the original Greek is “the end of this age.” This is a critical difference, since the end of this age and the beginning of the new one is ushered in by the Jubilee.

Passover and the Ides of March

The time of year here is important as well. Jesus was going to Jerusalem at the time of passover, whose date coincided with the Ides of March (around March 15th). At that time in the Roman Empire, the Ides of March was when taxes and debts were due - the end of the Roman Imperial fiscal year. Because it was when debts were due, it was also the time that debts were forgiven.

On the way to Jerusalem, Christ meets two men, who are both rich and who want to ensure they go heaven and are saved.

The first one says that he is doing all the right things – he’s following all the commandments. He wants to know that this will ensure him eternal life. Christ asks whether he gives to the poor, and the man balks.

This exchange is the source of one of the most famous biblical quotations, and mistranslations, of all time, when Christ is quoted as saying, “It’s easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the gates of heaven.”

It’s a well-known mistranslation – instead of camel, it’s actually a word closer to “cable.” That makes more sense for the metaphor – “it’s easier for a cable to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to pass through the gates of heaven.”

Then Christ meets another man, who tells him he is giving half of his money to the poor, and Christ assures him that he will be saved.

During this time, Christ is aware of the danger of what he is going to do. He knows he could be killed, if the local Roman Authorities think that he is stirring up trouble or a Rebellion against the Empire. But Rome is not what Christ is focused on – he is focused on the hypocrisy and the corruption in his own faith and his own temple.

Christ arrives at the temple, where there are peasants gathered with animals, interacting with the moneychangers and moneylenders inside. At that time, temples were also often banks. It is likely a misunderstanding that the peasants are offering their animals as a sacrifice: they have no money and are selling their animals to pay their debts.

This is part of what enrages Christ, and we see the only time he committed violence.

In his eyes, and in his faith, Christ believed that the poor should be freed of their debt, so they wouldn’t have to drag their last few goats or a couple of handfuls of pigeons to their lender, because they had no money left of their own.

In his eyes, what was happening was the corruption of His faith – instead of paying their debt to God by forgiving the debts of the poor, they were taking from the poor – turning the temple into a “den of thieves”.

That’s why he thrashed the moneylenders and flipped over their tables - to destroy their accounts. He is enraged at the both the dishonesty and the injustice of what is happening. Instead of paying their debt to God, by refusing debt relief, they are stealing from the poor.

In terms of spiritual law and the scripture, Christ is in the right. Immediately, the moneychangers turn on him – and try to trap Christ into incriminating himself with the Roman Authorities.

The trap they are setting for Jesus is a deadly one. They ask Jesus whether he also thinks that poor people shouldn’t have to pay their taxes to Rome? It’s a loaded question. While they’re suggesting he has a double standard, or that if he really wanted relief for the poor, why he’s not calling for a tax revolt. If he agrees, and says the poor shouldn’t pay their taxes, it can be seen as fomenting rebellion against Rome, for which he can be executed.

Instead, Christ pulls out a Roman coin – the currency in which taxes to Rome were paid – and asks whose face is on it. The answer, of course, is Caesar. And Christ stays true and consistent: “Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”

Christ expected adherence to the laws of faith and the laws of the civil authorities. You would be a responsible law-abiding citizen of Rome, and pay your taxes, and you would be paying your debt to God by either giving to the poor or reducing their debt, and in doing so would be to faithfully following the tenets of your faith.

Christ avoids being arrested, but the moneylenders aren’t done with him. They are the ones who give Judas the 30 pieces of silver to help identify Jesus so he can be arrested. Who else but moneylenders and moneychangers would have easy access to that kind of money?

Marvin L. Krier writes

“Biblical scholars and preachers have a number of interpretations of Jesus' cleansing of the temple. A standard interpretation is that Jesus was angered over the cheating by the moneychangers. The people who came to offer sacrifice at the temple had to exchange their coinage to use temple money to buy their sacrifice.

An uneducated peasantry could easily be taken advantage of by the unscrupulous moneychangers.

“The action of Jesus is a spirited protest against injustice and the abuse of the temple system. There is no doubt that pilgrims were fleeced by the traders.”

While this is a fair interpretation of the text, Jesus is also challenging a deeper injustice.

William Herzog argues that we cannot appreciate the meaning of Jesus' charge against the temple without some understanding of the economic role played by the temple in Jerusalem.

“The temple cleansing cannot be divorced from the role of the temple as a bank.

In the time of Jesus the temple amassed great wealth because of the half-shekel temple tax assessed on each male. Historical evidence supports the fact that large amounts of money were stored in the temple. The temple then was able to make loans on behalf of the wealthy elites to the poor. If the poor were not able to pay their loans, they would lose their land. "The temple was, therefore, at the very heart of the system of economic exploitation made possible by monetizing the economy and the concentration of wealth made possible by investing the temple and its leaders with the powers and rewards of a collaborating aristocracy.”

As evidence of this role of the temple funds, Herzog notes,

“It was no accident that one of the first acts of the First Jewish Revolt in 66 C.E. was burning of the debt records in the archives in Jerusalem.”

Though he was executed by Rome, Christ was not fighting Rome – he was fighting corruption in his own faith, for having forgotten, or suppressed, or ignored the rite of Jubilee, as a way of resetting the world, and the economy - and of doing so in a way that could be peaceful. It could even be democratic.

Yes, Biblical Jubilees actually happened

It is important to recognize that the Jubilee years of debt forgiveness, and a return to land were historical events. There is plentiful historical evidence that such jubilees did take place - and economist and historian Michael Hudson argues that some of the most important parts of the Bible, and Christ’s teachings, are often talking about the morality of handling debt contracts.

Hudson argues that in the Ten Commandments, “Thou Shalt Not Take the Lord’s Name in Vain,” is saying that it’s wrong to cheat someone by lying or swearing out a false oath – you shouldn’t be forging your signature or lying in a debt contract. When you sign it, you are swearing to God that it is true. This is telling people to be honest in their dealings, and not swear a false promise to God, or abuse people’s trust.

Likewise, Hudson argues that “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife” is not about adultery, it is about protecting women who are being held as collateral for debt. That is because, husbands in need of a loan might use their wives as collateral – they would be sent to live with the lender, essentially as a hostage, who would be released when the debt was repaid. The admonition was that the lender should keep their hands off the woman.

Because most debts were owed to the palace - or temple - it was possible to forgive them. They had to be forgiven because these ancient rulers and civilizations recognized something that we do not: that the interest on debt will always grow faster than the ability of economy to produce income to pay it back.

Those societies did not have our idea of time being a straight line, with things getting better with the “march of progress”. Rather, these societies, being agricultural, recognized the repetitive cycles of life. The jubilee year was an opportunity to reset and go back to the beginning. It was an opportunity for a clean slate - a literal one.

When people unearthed writing in the ancient near east, they discovered enormous numbers of clay tablets. When they translated them, they found that they were accounting books, tracking people’s purchases and debt. The clay was soft, so you could add to it and change it over time - but it was also possible to wet it and wash it clean - erasing the debt that was written there - hence, a “clean slate” or “wiping the slate clean.”

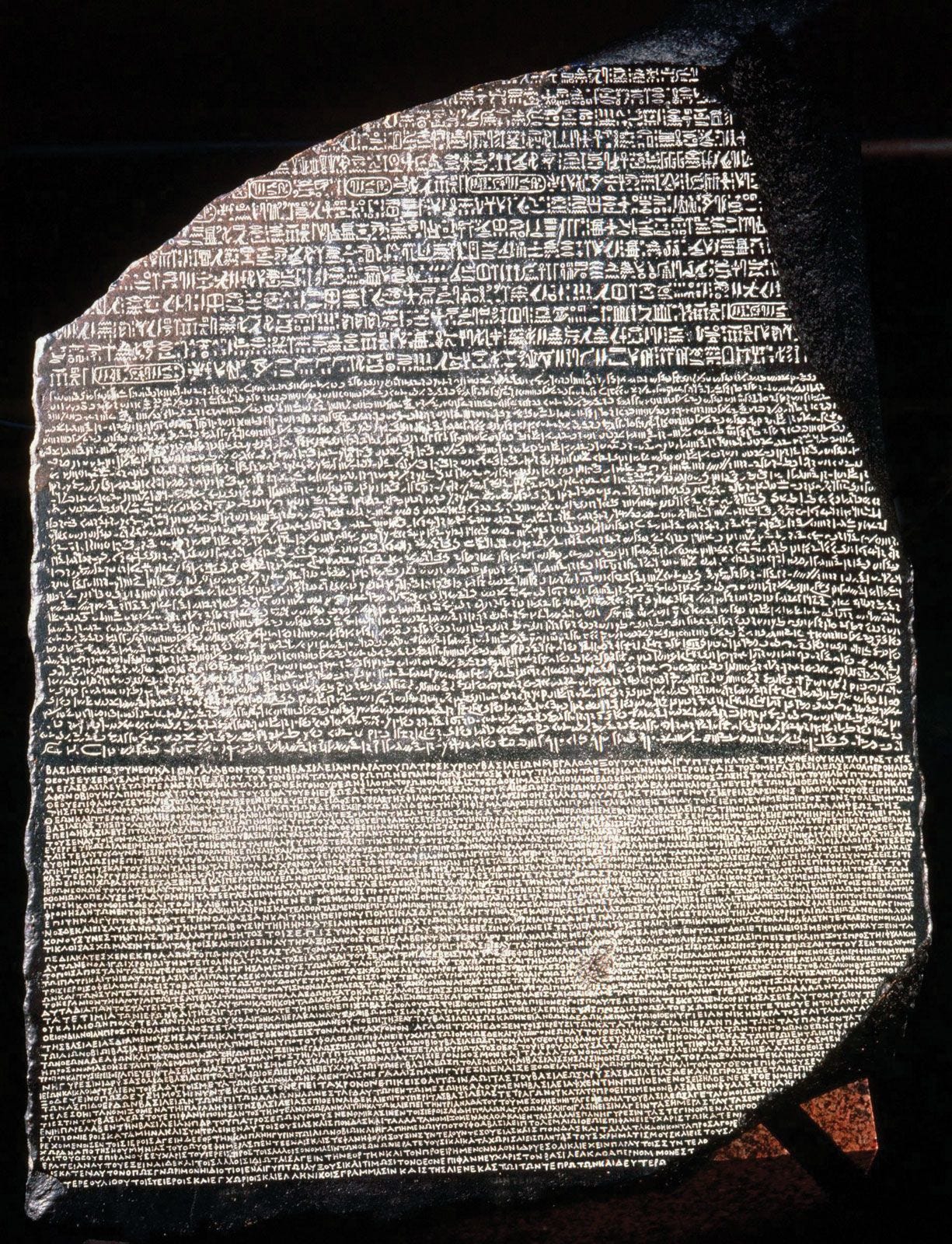

The Rosetta stone, which was a stone dating from 196 BC that had the same text carved in three different languages - two versions in Egyptian, and a third in Ancient Greek. It is currently in the British Museum in London. When it was discovered in 1799, it caused a sensation, because it offered the possibility of cracking the code of Egyptian hieroglyphs - and in fact did so. The term “Rosetta Stone” has come to mean a generic term to cracking a code or to translation.

Less attention has been paid to what was actually written on the Rosetta Stone. It was a decree - carved in stone, in three languages, proclaiming a new contract with the people of Egypt: debt forgiveness.

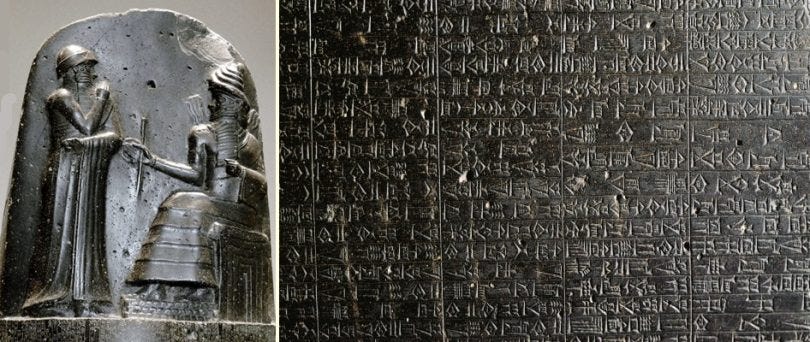

The Rosetta Stone is not the only stone of this type. The Hammurabi Code is a carved stone with a series of judgments and decrees, dating from 1762 BC.

“Hammurabi proclaimed the official cancellation of citizens’ debts owed to the government, high-ranking officials, and dignitaries. The so-called Hammurabi Code is thought to date back to 1762 BC. Its epilogue proclaims that “the powerful may not oppress the weak; the law must protect widows and orphans (…) in order to bring justice to the oppressed”

These debt jubilees were a regular feature of society in ancient Mesopotamia. They were recognized as a necessary reset because debt would polarize societies - a few rich getting richer while the many poor get poorer - driving people into to poverty and off their land.

The debts that were cancelled were personal in nature. Business debts - which were loans on productive enterprises - were not cancelled. And there were detailed rules to prevent people from gaming the system. For example - they would be back-dated, so people couldn’t rush out and take on more debt.

What changed? Michael Hudson argues that we were cut off from the Biblical tradition of debt forgiveness in two ways.

One was one of the famous decisions by Rabbi Hillel - who lived in the time of Herod. His Prozbul was a break from the tradition of the Jubilee, in that it allowed borrowers interest-free loans while also protecting creditors.

The other is that Christ’s teachings on debt and debt relief were overwritten by Roman laws and expectations that debts would always be repaid, or that land would be seized as a consequence.

Rome, too had a tradition of economy-wide debt restructuring: the reason Julius Caesar was assassinated by Senators on the Ides of March is that he was planning to provide debt relief. This was opposed by Senators, who were lenders who benefited from debt payments. As they say, history is written by the winners - in this case, the assassins. It marked the end of Rome as a Republic and its transformation into an Empire, because the the oligarchs were left in control.

Over time, rich landlords in the Roman Empire could grow ever-larger estates by foreclosing on poor peasants. There is little question from historical sources, that debt contributed to the fall of the Roman Empire.

There is a period that Hudson describes that sounds like our own:

“In addition to its military and debt problems, the ecological situation was worsening. Population growth led to over-cultivation and over-irrigation of the land, silting up of the canals and abandonment of alternate fallow seasons. An urban exodus ensued “toward the freedom of open and unpoliced regions,” concludes Oppenheim: “The concentration of capital within cities produced urban absentee landlords for whom tenant farmers worked; furthermore, it led to increased moneylending which, in turn, drove farmers and tenant farmers either to hire themselves out to work in the field or to join outcast groups seeking refuge from the burdens of taxation and the payment of interest.”

Wealth concentrated among a few in cities, absentee landlords, ecological problems, tenant farmers, tax avoidance and crushing debt. Does this describe the country where you live? Because the passage refers to Babylon in the 17th century BC - 3700 years ago.

All of this is important, because Biblical debt jubilees were also not taken seriously by modern interpreters and economists.

Debt forgiveness is seen as impossible, or immoral, and someone who finds themselves in debt is often chastised for “living beyond their means,” or it is assumed that they were reckless or lavish. Since some people are diligent and either avoid debt, or pay them back conscientiously, it is considered unfair to forgive the debts of those who can’t pay some or all of it the debt, with interest back.

The perceived unfairness of debt restructuring - or of debt forgiveness - is that the person who lent the money in the first place will not get all of their money back, as if they lent $1,000 and got only got back $500, and suffered a loss. The entire principle of lending with interest is that you have to pay back more than you received - often twice as much.

That is because we underestimate how quickly debt can grow and double due to interest. The financial reality for most borrowers is that they are being “harvested” for debt payments when the principal and much of the interest is still being paid.

The rule of 72 is a rough way of calculating financial timelines:

"Years to double = 72 / Interest RateAt 6% interest, your money takes 72/6 or 12 years to double.

To double your money in 10 years, get an interest rate of 72/10 or 7.2%.”

The gains pile up - as interest on interest. At 10% interest, a dollar will be $1.10 at the end of the first year, then 10% on that $1.10, reaching $1.21 in the second year.

Notice how the dime we earned the first year starts earning money on its own (a penny). Next year we create another dime that starts making pennies for us, along with the small amount the first penny contributes. As Ben Franklin said: “The money that money earns, earns money”, or “The dime the dollar earned, earns a penny.” Cool, huh?

This deceptively small, cumulative growth makes compound interest extremely powerful – Einstein called it one of the most powerful forces in the universe.

What are we to make of this?

What are we to make of these lessons, and this interpretation?

The reason people tend to reject the interpretation is that they are choosing to read the scripture metaphorically, instead of literally.

This is the literal meaning of the words, expressed in a way that is straightforward and clear and repeated several times over:

Forgiving the debts of the poor is paying your debt to God.

Obey the civil authorities and pay your taxes. (Holding a coin with Caesar on it: “Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s.

To return to social harmony and harmony with the land, forgive debts and let people return to land or property they had lost.

These lessons mesh perfectly with Christ’s other teachings on peace and forgiveness. This is the peaceful alternative to conflict that is tearing societies apart with bitter hatred - forgiveness for the wrongs of the past - including all the wrongs driving the reasons the debt can’t be repaid.

These lessons are the core of His message - and are arguably among his most important lessons because he preached it knowing he would be killed for it.

The “forgive us our debts” in the Lord’s Prayer, the Rosetta Stone and the Code of Hammurabi are not the only examples of a call for a debt jubilee being hidden in plain sight. Isaiah is a prophet in all the Abrahamic religions - Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

The traditional way in which jubilees were proclaimed were by holding aloft a torch - or with bells - hence the phrase “let freedom ring.”

There are also prominent economists today who are arguing for better debt restructuring and private debt forgiveness in order to renew society. It’s not about equality - it’s about making sure that everyone is over the break-even line.

“Many Christians are bound to experience some discomfort upon reading Hudson’s conclusions that the Bible is more about debts than sins. Even strict Marxists and some contemporary progressives may be challenged by the notion that religion has not in fact been the opium of the people, but an avenue for their redemption and a bulwark for their freedom throughout history. Nonetheless, the author’s work is scholarly enough to force most such stances into genuine reflection.”

DFL