Eating our young: the tragedy of Greek debt crisis, and the economic blunders that caused it

The IMF’s “Top staff misled their own board, made a series of calamitous misjudgments in Greece, ignored warning signs... and collectively failed to grasp an elemental concept of currency theory."

Above: Saturn (or Kronos) the Titan, devours his children rather than be overthrown by them.

After the global financial crisis of 2008, Greece became a cautionary tale for pundits and politicians who want to warn against “spending beyond your means.” The truth of what actually happened in Greece is a grim story of incompetence and wrongdoing on a scale so massive that there are no terms adequate to describe it.

We know this because an internal report from 2016 by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) makes it crystal clear that the economy and people of Greece were deliberately sacrificed in order to save the Euro currency and protect banks in France, Germany and the UK from their own reckless mistakes.

The UK’s Telegraph reported that the IMF’s “top staff misled their own board, made a series of calamitous misjudgments in Greece, became euphoric cheerleaders for the Euro project, ignored warning signs of impending crisis, and collectively failed to grasp an elemental concept of currency theory.”

The IMF report can be downloaded here.

As the Telegraph wrote at the time

“The possibility of a balance of payments crisis in a monetary union was thought to be all but non-existent,” it said. As late as mid-2007, the IMF still thought that “in view of Greece’s EMU membership, the availability of external financing is not a concern".

At root was a failure to grasp the elemental point that currency unions with no treasury or political union to back them up are inherently vulnerable to debt crises. States facing a shock no longer have sovereign tools to defend themselves. Devaluation risk is switched into bankruptcy risk.

“In a monetary union, the basics of debt dynamics change as countries forgo monetary policy and exchange rate adjustment tools,” said the report. This would be amplified by a “vicious feedback between banks and sovereigns”, each taking the other down. That the IMF failed to anticipate any of this was a serious scientific and professional failure.

(Emphasis mine)

The conventional wisdom is that the Greeks borrowed and spent too much, were lazy and didn’t collect their taxes enough. A simple problem - living beyond their means got them into trouble, so being forced to tighten their belts would solve it.

Except it wasn’t really true.

Are Greeks bad workers?

No, actually, they work some of the longest hours in the world - 600 more hours per year than the Germans, because their economy is mostly small businesses, and not large-scale manufacturing.

Did the cuts work?

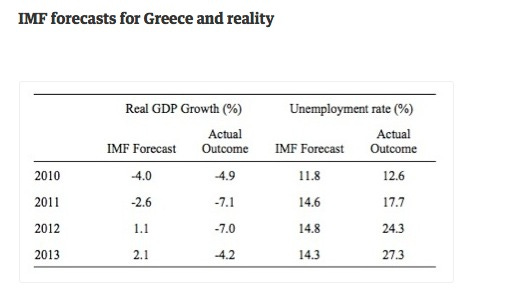

No. They were an economic and humanitarian disaster. In three years, the economy shrank by a third, adult unemployment soared to 25%, and youth unemployment hit 50%. Yaris Varoufakis, the Greek Finance Minister for Syriza, called it “fiscal waterboarding.”

Now the IMF agrees.

The Euro was always fatally flawed, because it created a currency union without any of the crucial mechanisms you need to make it work, and there are lessons here for every federation, including the U.S. and Canada - as well as for nationalists who want independence - like Scotland and Quebec.

Having monetary sovereignty - being a country with your own independent currency, and your own central bank, has trade offs.

An independent currency acts like a shock absorber - that can help countries cope with economic troubles. A central bank means that the government can always pay its bills, so long as they are denominated in its own currency.

If a country faces economic challenges, the value of your currency may drop, making your exports more attractive, which can help your economy pick up again.

If you have a currency union over several jurisdictions (like between provinces in Canada or U.S. states) transfer payments are essential for economic stability for the lower level of government and the economy as a whole. Transfers are not just about ensuring social services - they are the price of ensuring macroeconomic stability. This was the “elemental concept of currency theory” the IMF and everyone else ignored.

The Eurozone took away the ability of Greece and every country in the Euro zone to control their own currency. Then the “troika” of the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the IMF tried to “devalue” the Euro - just in Greece - by imposing austerity.

It is not an exaggeration to suggest that people have died as a consequence, because suicide rates were up and poor seniors were eating out of the garbage. Incredibly, from a fiscal point of view, Greece was a success, because in the midst of this, it was balancing its budget.

Did Greece fail on tax collection?

Yes. However, when Yanis Varoufakis and the Ministry of Finance set up a computer program that would scan government and banking databases to find tax cheats, the Troika and the Greek government scrapped the program after he was forced to resign. It did not help that the President of the European Commission was from Luxembourg, a tax haven.

What about the hundreds of billions in bailout money for Greece?

It never made it to the people. Between 60% and 95% of the bailout flowed straight back to its creditors - mostly banks in the UK, Germany and France, who had bought huge amounts of risky bonds from countries in the EU periphery - as well as Spanish mortgages and more.

One of the ideas behind having a common currency - in addition to a common market, in Europe - was the idea that it would reduce volatility and debt issues associated with independent currencies.

In the 1990s, interest rates, including on government debt in countries like Greece were approaching 20%.

The idea behind the Euro as a currency was that if it were applied across the entire Euro zone, it would eventually bring down risk, and interest rates, in order to create greater stability and prosperity.

However, all those high-interest bonds were investments that paid pretty well, and as the interest rates dwindled, there were fewer and fewer places for investors to put their money and get that kind of return. As a result, the bonds, which were fairly few and thinly traded, were snapped up by European banks.

As interest rates dropped in those new Eurozone countries, people who did qualify for loans could get larger ones, and people who had never qualified did. In Greece, there were already high levels of home ownership - so banks encouraged people to take on lines of credit.

The lending that was taking place in Spain, France, Greece and other countries in the “euro periphery,” where interest was high, was often from “core” banks.

Mark Blyth tells the story here - quite incredible.

So, core European banks snapped up risky bonds from the countries about to enter the Euro - bonds with 25% interest rates, a 1 in 4 chance of failure - thinking they would get bailed out by the EU or the European Central Bank if things went sour. They were wrong.

Political unrest and populist movements are surging because of a global crisis in authority: experts and elites in both government and business promised that trade deals, free markets and low taxes would lead to prosperity for everyone, but they haven’t.

They have paid off well for the people at the top, but in stagnation for everyone else. But the lesson of the IMF and Greece is worse: it is an object lesson in how the weak have been forced to pay for the mistakes of the strong.

These financial catastrophes quite clearly have enormous geopolitical consequences, but they have domestic consequences as well.

Separatist and nationalist movements get traction in financial crises - people are suffering, and they want it to stop, and they believe that either replacing the government or breaking away from it for independence will solve the problem.

Financial Sovereignty Matters

In Europe, this resulted in Brexit, and there are separatist movements in Canada - certainly Quebec, but also some in Western Canada. Scotland talks about becoming independent of the UK.

In each of these cases, the question of what currency that an independent country would use is discussed, but not very seriously - and not as seriously as it should be, given that it is essential to any functioning national government.

There have also been times where people have asked whether Canada should just take adopt the U.S. dollar. It would come at a price - a significant one, which would be that Canada would no longer have control over its own economy.

This aspect of monetary sovereignty - of having your own currency, and a central bank that can create money or take other measures in event of a crisis is incredibly important.

What happened in Greece shows the dangers - even the people who are supposed to be the world experts in this - the International Monetary Fund, plus platoons of economists, experts and politicians. While creating a new currency for over 300-million people living in Europe, representing one of the largest economies in the world, they “ignored warning signs of impending crisis, and collectively failed to grasp an elemental concept of currency theory.”

There are still fundamental flaws in the way the Euro and the European Central Bank were set up. What is needed - an effective automatic transfer payment system (which was proposed by the IMF) are required as shock absorbers to compensate for the differences in economic activity, as well as being an essential price we pay for living with a shared currency.