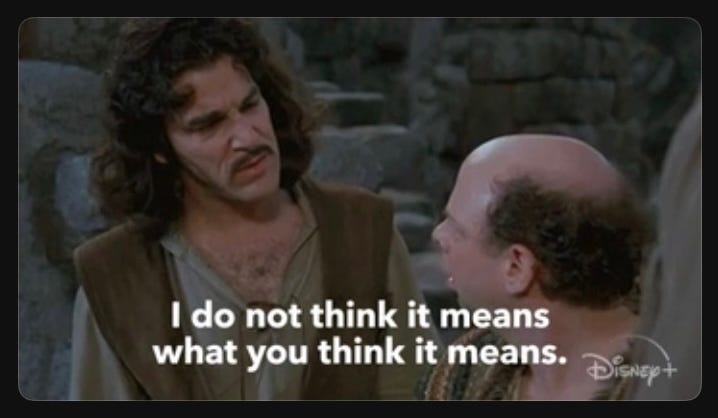

Fiscal Conservatism? "I do not think it means what you think it means."

Some clarity on why Fiscal Conservatism isn't Fiscally Responsible. Instead, it's fuelling the crises that are dividing us and undermining democracy.

The current fundamental challenge in this age for centrists, liberals and social democrats, reality-based conservatives and indeed, everyone seeking to defend liberal democracy, is that we need to show that it can work, be effective, and work better than the alternative.

Governments need to deliver the relief that’s needed. We are in a crisis - multiple crises - and that starts with recognizing that fiscal conservatism and neoclassical economics need to be challenged, because they are breaking our economies and our democracies.

Ideas and details matter, especially in the era of "post-real" economics. Politics can drain words of their meaning.

People often complain about the dumbing down of politics, of cynical manipulation, of negative campaigns and of the lack of genuine debate or shared reality.

One of the issues is pretty simple, however - we can’t even agree on what certain terms mean - because political positions are immediately being torn apart, parodied, mocked or distorted by opponents, overblown rhetoric, or a party’s own propaganda.

The label that is pinned on a political opponent, or on your own chest can be either a badge of virtue or a mark of shame - capitalist, communist, liberal, woke, conservative, socialist - but a badge is all it will be.

In their political use, the specific meaning is lost: it all just means either “good” or “bad”. The fact that someone is a capitalist, a socialist or a liberal is enough. So a lot of what passes for political discourse is really just trafficking in stereotypes, with labels slapped onto people stickers on an old suitcase, which are all just ways of saying you are good and your opponent is bad.

Of course, all of these political ideas are worldviews - and they have real ideas behind them that will affect the way people are governed - their prospects and prosperity. There are real consequences to these ideas - good, bad and unintended.

One of the ideas that has become a default is the idea of fiscal conservatism - It is a default in ways that people do not appreciate.

Over the last decades, it has become common for people positioning themselves as “centrists” - and liberals - to declare that they are “fiscally conservative but socially liberal” as a way of splitting the difference between two imaginary political camps of left and right. This is the mullet of political compromise: business up front, party in the back.

There is more to fiscal conservatism than just thinking that governments shouldn’t be fiscally reckless, which is something no one wants. It is a quite specific set of economic ideologies and policies.

The issue with fiscal conservatism is that when put in practice, it actually leads to destabilizing fiscal and economic results. Fiscally conservative policies led to the Great Depression nearly a century ago, and led to the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-2009. It’s worth unpacking what fiscal conservatism means - because it also involves confusion around the many definitions of the world “liberal” and “socialist”

Classical Liberals & Socialists & the Free Market

The people we present as “political thinkers” were often propagandists. They were not just analyzing the world to see how it worked: they were making economic and political arguments for the sake of a constituency. John Locke was a propagandist for the up-and-coming merchant class. David Ricardo, who is still cited as a theorist on international trade, was a lobbyist for bankers. His brothers foreclosed on Greece in the 1800s.

That century had its fair share of revolution and debate about what kind of governments and democracy would prevail around the world, with vital arguments around democracy, freedom and slavery.

Economics is sometimes called “the dismal science” and the reason for it is grim. The phrase comes from a racist essay “Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" by Thomas Carlyle, a Scottish philosopher, who was lamenting the abolition of slavery, arguing that slaves would end up idle, as the Irish were (the Irish were, at the time, experiencing a famine).

In the 1800s and 1900s, the word “liberal,” when applied to politicians, political economists and philosophers, was that they were generally in favour of freedom and free trade. They were “classical Liberals”, and they generally supported “classical economics”.

The term “Liberal” keeps shifting, and as Ha-Joon Change writes in his excellent book, “Economics: A User’s Guide”

'LIBERAL: THE MOST CONFUSING TERM IN THE WORLD?

Few words have generated more confusion than the word 'liberal'. Although the term was not explicitly used until the nineteenth century, the ideas behind liberalism can be traced back to at least the seventeenth century, starting with thinkers like Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. The classical meaning of the term describes a position that gives priority to freedom of the individual. In economic terms, this means protecting the right of the individual to use his property as he pleases, especially to make money. In this view, the ideal government is the one that provides only the minimum conditions that are conducive to the exercise of such a right, such as law and order. Such a government (state) is known as the minimal state. The famous slogan among the liberals of the time was 'laissez faire' (let things be), so liberalism is also known as the laissez-faire doctrine.

Today, liberalism is usually equated with the advocacy of democracy, given its emphasis on individual political rights, including the freedom of speech. However, until the mid-twentieth century, most liberals were not democrats….

What makes it even more confusing is that, in the US, the term 'liberal' is used to describe a view that is the left-of-centre. American liberals', such as Ted Kennedy or Paul Krugman, would be called social democrats in Europe.

In Europe, the term is reserved for people like the supporters of the German Free Democratic Party (FDP), who would be called libertarians in the US.

Then there is neo-liberalism, which has been the dominant economic view since the 1980s.. It is very close to, but not quite the same as, classical liberalism.

Economically, it advocates the classical minimal state but with some modifications - most importantly, it accepts the central bank with note issue monopoly, while the classical liberals thought that there should be competition in the production of money too. In political terms, neo-liberals do not openly oppose democracy, as the classical liberals did. But many of them are willing to sacrifice democracy for the sake of private property and the free market. (Emphases mine)

As Ha-Joon Chang further explains, while Marx analyzed capitalism and called for its replacement with a revolution, others called for reform.

Marx and many of his followers - including Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Russian Revolution - believed that a socialist society could only be created through a revolution, led by workers, given that the capitalists would not voluntarily give up what they had. However, some of his followers, known as the 'revisionists' or social democrats, such as Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky, thought that the problems of capitalism could be alleviated through the reform, rather than abolition, of capitalism through parliamentary democracy. They advocated measures like regulation of working hours and working conditions as well as the development of the welfare state.

Whether they were Marxists or the equivalent of 19th century libertarians, they were all looking to change the system of government they were living under, which was still feudalism. They wanted to find a way to run their countries without paying exorbitant rent to hereditary aristocrats, who took money for nothing.

It has been argued that in one sense liberals, classical liberals, Marxists and social democrats were all socialists, because they wanted to replace feudalism with a different kind of government that would run the country, instead of Kings, Queens and aristocrats. They were not “socialists” in the sense of the kind of Marxist-Leninist Communists who thought that the government should own everything, and everything would be centrally controlled.

They were all also in favour of the “free market” - because they were not talking about a market free from government intervention, regulation, or taxes - it was a market free of the extra costs and burden of rentiers - people who earn money from capital without working. That was a real burden on the economies of Europe in the 1700s and 1800s was the burden of supporting an aristocracy. Tenant farmers paid landlords, and people who were without land - without a “bond” were vagabonds.

Even in Britain today, the largest landowners and wealthiest individuals are those who benefited from a distribution of land after the Norman invasion of England of 1066. Even today, “Just 0.3% of the population – 160,000 families – own two thirds of the country. Less than 1% of the population owns 70% of the land.” It should go without saying, that feudalism is a very different model than a government that provides services and public works in exchange for taxes paid.

The colonization - and wealth of the "New World” was driven in part by the fact that “Old World” of Europe had an aristocracy that added to the cost of overhead for everything by driving up the cost of property, making the entire economy less competitive. By contrast, the wealth and prosperity of North America was directly related to the fact that they took land - and redistributed it to settlers, sometimes for free. Instead of being tenant farmers, people had land of their own.

Upheaval and Technology: Steam, Rail and New Economies

The social and political changes are also driven by innovation and changes in technology, which are disruptive in a number of ways. If a new innovation massively increases the productivity of one worker, many other workers may face permanent wage losses or unemployment. Colonization was also driven by technology in transportation, weapons, and public works - steam ships and railroads quickly reaching parts of the globe that had been inaccessible except through colossal effort.

The Industrial revolution in the UK had the effect of plunging people into poverty, and in some areas live expectancy dropped under 30, the lowest it had been in 800 years. Around the world, Indigenous populations were being wiped out, sometimes through deliberate and malicious means - engineered famines and deliberate killings - and sometimes due to exposure to new diseases.

Medical innovations also cause disruptions as well. In 1850, modern medicine did not exist. Bacteria and viruses were unknown, and basic sterilization techniques were actively opposed by the medical establishment.

New innovations, cures and treatments from vaccines to insulin, vitamins, diagnostic and surgical techniques also create ethical, moral and political dilemmas we are still wrestling with today.

Because as a basic rule, while anyone can fall ill, not everyone can pay. A new cure creates new questions: “Whose life gets saved? And how do we choose?”

These innovations create political pressures for government to step up, with forms of public insurance - pensions, health insurance - a so-called “welfare state,” to which fiscal conservatives have generally been opposed, because government is perceived as a “cost” and “overhead” that is a burden to, takes away from, or otherwise upsets the private market.

However, there is a real difference between paying aristocratic rentiers vs paying taxes every year that are reinvested in the well-being of citizens.

Government as co-investor in growth and prosperity

There is a different point of view, which is that government investments of a welfare state enhance not only improve social conditions, but they enhance economic prospects. Public infrastructure (transportation, energy, water, trade), public education and public health care are all money being spent into the economy in ways that enhance both lives and the standard of living.

That was the argument made by Simon Patten, the first professor of economics at Wharton from from 1896 to 1912.

Simon Patten, the first professor of economics at America’s first business school, the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, defined public infrastructure as a “fourth factor of production,” in addition to labor, capital and land. But unlike capital, Patten explained, its aim was not to make a profit. It was to minimize the cost of living and doing business by providing low-price basic services to make the private sector more competitive.

Unlike the military levies that burdened taxpayers in pre-modern economies, “in an industrial society the object of taxation is to increase industrial prosperity”by creating infrastructure in the form of canals and railroads, a postal service and public education. This infrastructure was a “fourth” factor of production. Taxes would be “burdenless,” Patten explained, to the extent that they were invested in public internal improvements, headed by transportation such as the Erie Canal.

As opposed to private interests, if governments provide common infrastructure (water, bridges, roads, ports) they would lower the overhead costs for the entire economy - families and businesses alike. The same can be argued for public education as well as health care.

In other words, what is usually considered a “cost” to the economy - taxes that provide infrastructure, health care and education, these are all benefits that help grow the economy much more than it would otherwise.

This “welfare state” - so named because the state looked after the welfare of its citizens - is now equated with “socialism” and interference with the “free market”. This turns the entire motivation for 19th century reforms on their heads.

While governments preached laissez-faire, every wealthy country in the world became wealthy through protectionism. Britain, Japan, Germany, and the U.S. were all highly protectionist as their economies developed, and only after they were wealthy did they start demanding free trade agreements with other countries. Throughout the 1800s, the trade agreements established by Britain were one-sided. It is widely taught that the reason the Great Depression was made worse because US politicians decided to increase tariffs - the so-called “Smoot Hawley” tariffs. US tariffs on manufactured goods were about 30% for more than a century, until the 1930s. The fact that tariffs were already so high is one of the reasons why Smoot and Hawley aren’t actually to blame for making the Depression worse.

Before and after the Market Collapse of 1929

What caused the “roaring 20s” was an economic scenario similar to the one we have had for the last decade (or longer).

In the U.S., dropping interest rates led to easy money and lots of lending. The economy was split - the 20s roared for stock market gains and property speculation - it was a gilded age, like Great Gatsby - but not everyone was getting a share. It wasn’t just the stock market - it was also real estate speculation. That’s why people used to joke about people being gullible, saying “If you believe that I’ve got some swamp land in Florida to sell you.”

Leading up to 1929 people were borrowing money to speculate on assets - taking out money, with interest, to gamble on whether real estate and the stock market would keep soaring. Of course, most people who need houses aren’t investors - but they get caught up in it, and as prices rise, they have to borrow to buy, too.

Would you borrow $300,000 or $500,000 to buy an asset that could drop in value?

You might say no - but have you bought a house in the last five years?

When manias happen, a key part of what happens is that the explosion in debt and speculation undermines the rest of the economy first, before collapsing.

Two feedback loops get set in motion:

The first self-reinforcing feedback loop is that the more people borrow, the more it drives up prices, the more the bets pay off - and more creditors are willing to lend. Because continuous lending keeps driving up prices, it creates the illusion that these kinds of investments are safer than they actually are. Because everyone is making money, it is difficult to argue that it is a sham.

The second feedback loop is that the more the debt-and-gambling-on-assets part of the economy grows, the harder it is to make a living in the rest of the economy. Some people leave the “real” economy for the speculative economy. There is a bigger problem, which is that if the speculation is on property it drives up the cost of overhead for the whole economy.

Housing, business, farms - if the cost of land goes up, and people are paying interest on it, it raises the cost of living and the cost of doing business.

“Real” “brick and mortar” businesses can start to go under. They are snapped up by speculators, who can afford it because they can borrow “easy money” in large quantities at low interest rates, to snap up distressed companies. The “real economy” struggles as the financial economy - and the folks in the bubble - thrive.

This might sound like today - where Wall Street and Bay Street investors and oligarchs are thriving while mainstreets are filled with boarded up store fronts. It’s not new: it also happened in the 1600s in the lead-up to the financial crisis that preceded the 30 years war. Farmers walked away from their ploughs because there was more money to be made in speculation.

For the bets to keep paying off, prices have to keep going up, because people have to keep borrowing.

It does not require an outside shock to trigger a crash - it only requires prices to stall, at which point the bets stop paying off, and the whole thing reverses itself. The lending stops, prices fall, borrowers can’t pay their loans. Some lenders may go broke. The house of cards collapses, because there wasn’t real value to back the money in the first place - it was private credit.

The 1929 Crash

The U.S. market crash in October 1929 was the beginning of an economic crisis that led to 15-million Americans losing their jobs, and hundreds of banks going under. Farmers went broke and crops rotted in fields. It lasted years.

That’s the difference between a “recession” and a “financial crisis.” In a recession, unemployment goes up, and a few businesses - in a financial crisis, banks and the economy fails.

When a bank fails, it called a “bank run”. You might have seen something like it in the Christmas classic, It’s a Wonderful Life, where the town panics and wants to withdraw all the money from George Bailey’s Savings and Loan.

What’s actually happening with banks is arguably different.

The bank isn’t going broke because everyone is pulling their money out. The bank has already run out of money because people and businesses are going bankrupt, and the bank has just lost all those regular streams of revenue they thought they could count on for years or decades from mortgages and other loans. That money is not going to be paid back - not the monthly payment, not the rest of the mortgage.

The bank itself is like a fuse or a breaker failing, and when it fails, it also means that the private source of new money flowing into the economy has been cut off.

After 1929, the U.S. stock market plunged - eventually losing 95% of its value. It had global implications, and the value of commodities and stocks plunged while banks went broke. Farmers were bankrupted because the value of their crops plunged.

The response from the U.S. government was to let everyone go broke. The Secretary of the Treasury, Andrew Mellon famously said to “liquidate everything” - farmers, everyone. He said it would “purge the rottenness” from the system so that people with talent could thrive. Given that Mellon had been Treasury Secretary from 1921 to 1932, he was also directly responsible for creating the conditions that made the crash possible, before making it worse by refusing to intervene.

The psychology of this reaction - austerity - is understandable in two ways. One is emotional, the other is based on bad reasoning.

The emotional reaction is the one being expressed by Mellon, which is one of punishment. In a crisis, people look for a scapegoat, and there is an emotional and moral sense that people were irresponsible, and now they need to be disciplined and corrected, to teach them a lesson. It’s the idea that we have economic hangover we’ve got was from partying too hard, we somehow deserve to be punished for it. It “provides satisfaction” in the old phrase, even though at the level of the whole economy, it is counterproductive and destructive.

Mellon was also following the usual, “Classical Liberal” economic solution would be that the government should stay out of it, because the market would eventually take care of it, you just had to wait and the market would right itself.

The idea, and assumption here was that once prices dropped far enough, and wages dropped far enough, that eventually, people would start buying again and businesses would start hiring again, through deflation. This assumption of “market equlibrium” is that the economy as a system will recover only if left to its own devices is just that - an assumption, and a problematic one at that, because in the real world, there may be new return to balance, at all.

Because markets are based on human activities in the real world, they can collapse or run out. Mines are emptied of their ore, natural resources are depleted, stocks of fish or birds are driven to extinction, human institutions fail and are never rebuilt. That is the historic and empirical reality of the world we live in, but classical economics operates from a position of denial that any such collapse can even happen.

The premise of the market as self-regulating and self-balancing is that it must be left to run undisturbed. Because the market it pure and perfect, and any deliberate intervention by government will keep it out of balance.

Of course, this is not a tenable argument. The market is still a human system - and there are market crashes going back centuries.

There’s another missing piece of the puzzle, which is debt and banks. In the 1920s, (just as in the last two decades) interest rates were low, so many people took on debt. After a crash, lots of people and businesses are still left standing, and they don’t default on their debt, but their own income may drop. Inflation makes debt easier to pay off. Deflation makes debt harder to pay off. This is Fisher’s paradox – “The more you pay, the more you owe.” It’s why austerity after a debt-driven boom makes things much worse, not better.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt Redefines “Liberal" & the Birth of Fiscal Conservatism

In 1932, Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) runs for President and starts to implement a “New Deal,” with public works, bank and monetary reforms - a huge change in ideology and policy.

Even though he is implementing all these progressive policies, FDR keeps calling himself a “liberal.” He’s not calling himself a socialist, or a communist, or anything else. When asked, he described himself as centre left. But this is a key point, because this is when, in the US at least, the word Liberal takes on this progressive “modern” association with New Deal policies, the welfare state, and being anywhere at all left of the political centre.

In response, people who formerly called themselves liberals, but who opposed FDR’s policies because they believed in “classical liberal” economics, renamed themselves as “fiscal conservatives.”

In other words, fiscal conservatives are people who opposed the policies of FDR’s New Deal, including regulating the financial industry and spending to get the economy going again. What’s more, they believe in a particular kind of economics - classical economics. They continued to argue that FDR’s plan was a mistake.

Those classical liberal economics - fiscal conservatism - are the policies that created the conditions for the market collapse, and are the same policies that extended the misery.

From the the New Deal to Neoliberals

There are still those who argue that FDR’s policies dragged out the Depression, because by introducing New Deal policies that put people to work, the government wasn’t letting the market bottom out enough.

But FDR’s “New Deal” policies put people to work, worked with the private sector to create jobs, and brought in new regulations to prevent financial crashes like the one that happened. The theory that was associated with the New Deal and this new kind of Liberal thinking was British Economist John Maynard Keynes.

The problem for Keynes - and other policymakers to follow - is that he did not express all of his theories mathematically. Keynes did not have a model for the entire economy.

As a result, people still kept using some neoclassical models to interpret his work. Some other ideas got attached or attributed to Keynes, even though they were not part of his ideas.

The challenge for Keynes and other economists like Minsky who studied and described the economy, they did not have complete mathematical theories to describe the phenomena that were apparent to them. That is, in part, because their theories accepted a great deal more complexity and uncertainty than classical models or models that are based on engineering or physics. It is difficult, especially in an era before computers, to develop mathematical models that would describe the economy that included uncertainty. How do you factor in all the information you don’t have?

There was a brilliant engineer and economist from New Zealand, Bill Phillips who decided to model the economy hydraulically. In fact, he built an analog computer, MONIAC, with containers with different levels of fluid connected by pumps and valves, representing money in different parts of the economy. It provided a dynamic way to make calculations in the economy, and in fact is a very sophisticated way of quickly generating answers to otherwise very complex math calculations in the absence of digital computers.

Phillips also wrote a very famous paper in 1958 in which he noted a connection between inflation and unemployment. When unemployment is low, lots of people are working and it’s a “tight job market”, wages go up, so firms put up their prices. It was called the “Phillips Curve”. It was based on date from the United Kingdom.

This idea - which was not part of Keynes’ theory - became associated with “Keynesian” policies, especially in the U.S. It was used to justify certain policies, and the assumption was that if inflation was a little higher, it was because workers were getting raises, and the job market was tight. That used to be the sort of thing that was good news for politicians.

Then, in the 1970s, a series of economic changes hit. The U.S. ended the global gold standard, but the U.S. dollar would now be the global reserve currency, because oil would be priced in American dollars. There was an energy crisis, as OPEC hiked the price of oil. The Vietnam war was still raging.

The result was inflation - but not wages going up: stagflation, which is something that the economist Milton Friedman had predicted, but the Phillips Curve did not.

This was used as a pretence to throw out, not just the Phillips Curve, but to reject all Keynesian ideas, and bring in Milton Friedman’s ideas, along with a newly updated version of classical economics - the fiscal conservatives who used to be classical liberals. That’s they were called - Neoliberals.

They were trying to reclaim the word “liberal” while they had a not just an ideology, but a specific set of mathematical formulas to model the economy, all of which was a throwback to a previous age.

The new economic model, being “neoclassical” was based on the classical liberal ideas that caused the Great Depression, and opposed the New Deal, and who then rebranded themselves as fiscal conservatives.

That is where the expressions “Neoclassical” and “Neoliberal” came from. It was a mid-1970s rebranding of ideas from the 1800s up until 1930 - ideas that rejected the entire New Deal and everything after it. They were so far to the right that it is not an exaggeration to say they wanted to repeal everything that happened after 1930 so they could return to the roaring 1920s, and that is what has been happening in the U.S., and to some extent in other countries, for 40 years.

As “Neoliberals” they could support all these incredibly regressive measures, while still having the word “liberal” in their name, which might make them sound somehow moderate.

In fact, the neoclassical ideas were even worse - they are “neoclassical economics” on steroids.

The people who came up with neoclassical economics, which is supposed to model the whole economy, didn’t even include banks, money, or debt. It is impossible for markets to crash or for depressions to happen in this model.

They insisted, in developing the math for the model, that “macroeconomics” needed to be built on a “foundation” of microeconomics. You might think that would mean they would figure out ways to model many small interactions at the micro level then add everything up at the end. After all, just look at video games or realistic CGI and robotics and you see that in other industries, we have the capacity to make millions of calculations based on complex models and interactions. You would think we might have a model of our economy that is something like that that guides the decisions of politicians, investors, central bankers.

You would be wrong.

The way that the economists who developed the theory, is just to treat the whole economy as one giant person, who is just the average of everything in the economy.

Economists “scaled up” one single person, who is the only person in existence. That one person represents the whole economy: they own their own business, where they are also the employee who makes the only product in the economy. They are also the only customer. Whether they work or not is up to them - so if you’re unemployed, it’s because you chose to be. And because it’s assumed you put money in the bank, and the bank lends it out, all the debt in the world cancels out, so you don’t need to measure it, so money, debt, and banks are not modelled. If there’s a change in markets, it’s because of a change in technology, or taste - not debt crises.

So, neoclassical economists will say “Yes, the economy slowed down after the housing crash, but they can’t blame the financial sector” because, according to their theories, the financial sector doesn’t exist.

From a political point of view, this is incredibly convenient for the financial sector, because the world’s most prominent economists will happily explain to the public and politicians alike that the banks had nothing to do with it.

Outlawing Keynes: Limiting political choice for leaders and voters alike

For many voters in developed nations, this is the reason there has been little choice in elections and policy platforms.

These neoclassical economists and their theory are the reason that, since the 1980s and 1970s, no matter what country you lived in, who you voted for, or whether the political party claimed to be left, right or centre, the default ideology is fiscal conservatism.

Branding this new, more extreme version of fiscal conservatism as a form of liberalism was a way of sugar coating the real goals of the movement, which was the rejection of Keynes and systematic dismantling of the programs, policies and regulations of FDR’s New Deal, on a national and international basis.

To enforce fiscal conservatism, its proponents have gone to extraordinary lengths to ensure that it is the only ideology that can govern, no matter who is elected. Balanced budget laws, balanced budget amendments to constitutions and to treaties have been recommended and passed.

Manitoba has a balanced budget law, which is supposed to punish Ministers who run a deficit with a pay cut. It has been amended 11 times, by both governing parties, in order to ensure Ministers don’t. The law, as such, has never remotely encouraged a balanced budget in the province, and all it really does is highlight the hypocrisy of politicians.

In other jurisdictions, it is much more serious.

The debt brake rule enshrined into its constitution in 2009 to bring stability and strengthen confidence in public finances during the global financial crisis was hailed as a victory for economic prudence at the time, rarely practised elsewhere. Now economists and policy-makers are referring to it as a veritable straitjacket, which Germany has managed to put on itself.

The EU Maastricht Treaty is likewise being described as a “straitjacket” as well because its “Stability and Growth Pact” which essentially imposes austerity on member states. European Institutions, including its central bank, are generally prohibited from providing assistance to member states - who, having given up their own currencies, have lost the ability to adjust to economic shocks.

In preparation for the introduction of the single currency, the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) was adopted in 1997 at Germany’s request to guarantee sustainable public finances in the long term. The pact was to prevent governments from accumulating excessive debt that would endanger the stability of the euro. The 3%-deficit and 60%-debt rules that the SGP institutionalized can be traced back to the Maastricht Treaty’s convergence criteria that had to be fulfilled by member states to join the common currency.

It’s somewhat surprising, that no one has commented on the just how draconian these laws are in a democracy. There has been a consistent, decades-long attempt to actually outlaw Keynesian economic theory - to make it illegal for politicians to have anything but a fiscal conservative viewpoint.

This is very serious problem on multiple levels - for democracy, as well as for policy.

First, it is not as if Keynesianism is an extreme ideology. It was the dominant economic theory during the “Golden Age of Capitalism,” from 1945-1975, when the world saw the creation of new unparalleled prosperity. It ended the Depression and helped win the Second World War for the U.S.

But outlawing Keynesianism in laws treaties and constitutions means that whoever gets elected, they are going to have to accomplish their goals within the straitjacket of fiscal conservatism - because fiscal conservatism is absolutely not the same thing as being fiscally responsible. Fiscal conservatism actually creates the conditions for crises and then leaves us unable to deal with them.

These ideas - neoclassical, neoliberal fiscally conservative ideologies - serve as the fundamental operating system of the economy, and have done for 40 years.

Political parties and their ideologies sit on top of the that operating system, like an application on the computer. In our current system, the political parties can update and change their software all they want, but it won’t change the operating system. Everyone involved - politicians, bankers, economists, experts - believe, or are being told, that this is the only way it can work.

To give an example from Canada: during the 2008 financial crisis, Marc Lavoie, who is a professor of economics, ran into Jack Layton, the Leader of the New Democratic Party of Canada (NDP) at the Ottawa airport. The NDP is considered to be Canada’s party of the left.

Why are we still doing this?

In the 1970s, all of Keynes was thrown overboard because a formula unrelated to his theories - the Phillips Curve - failed to predict stagflation.

Since then, there have been far worse crises. In the 1980s and 90s, there was widespread deregulation of finance and lending as New Deal policies and legislation was dismantled, by Republicans and Democrats alike.

Between 1940 and 1980, there were virtually no financial crises. Since 1980, there have been dozens - including currency crises in Russia, Mexico and Asia in the 90s.

Robert Lucas was one of the main economists who developed neoclassical economics in the 1970s.

“In a presidential address to the American Economic Association in 2003, Robert Lucas, Nobel prizewinner and one of the most prominent macroeconomists in the world, put it plainly: ‘Macroeconomics was born as a distinct field in the 1940s, as a part of the intellectual response to the Great Depression. The term then referred to the body of knowledge and expertise that we hoped would prevent the recurrence of that economic disaster. My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.’”

This quote has, been used many times to point out just how out of touch and overconfident the experts were. It is a bit like one of the designers of the Titanic boasting that the central problem of icebergs in shipping lanes had was a thing of the past.

That’s because five years later, in 2008, the entire global financial system went into meltdown.

Romer was unsparing in his criticism because during the same 2003 lecture Lucas had made, Lucas had backed another economist and colleague, apparently reversing his own previously stated opinion in favour of one that minimized the role of central banks and monetary policy in the economy.

“In his 2003 Presidential Address to the American Economics Association, Lucas gave a strong endorsement to Prescott’s claim that monetary economics was a triviality.

This position is hard to reconcile with Lucas’s 1995 Nobel lecture, which gives a nuanced discussion of the reasons for thinking that monetary policy does matter and the theoretical challenge that this poses for macroeconomic theory.”

I agree with the harsh judgment by Lucas and Sargent (1979) that the large Keynesian macro models of the day relied on identifying assumptions that were not credible. The situation now is worse. Macro models make assumptions that are no more credible and far more opaque.

I also agree with the harsh judgment that Lucas and Sargent made about the predictions of those Keynesian models, the prediction that an increase in the inflation rate would cause a reduction in the unemployment rate. Lucas (2003) makes an assertion of fact that failed more dramatically:

My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades. (p. 1)

Using the worldwide loss of output as a metric, the financial crisis of 2008-9 shows that Lucas’s prediction is far more serious failure than the prediction that the Keynesian models got wrong.

So what Lucas and Sargent wrote of Keynesian macro models applies with full force to post-real macro models and the program that generated them:

That these predictions were wildly incorrect, and that the doctrine on which they were based is fundamentally flawed, are now simple matters of fact ...

... the task that faces contemporary students of the business cycle is that of sorting through the wreckage ...(Lucas and Sargent, 1979, p. 49)

He goes on:

… The trouble is not so much that macroeconomists say things that are inconsistent with the facts. The real trouble is that other economists do not care that the macroeconomists do not care about the facts. An indifferent tolerance of obvious error is even more corrosive to science than committed advocacy of error.

Beyond “Post-real” Economics

In a world where so many people are concerned about threats to democracy, misinformation, disinformation, and “fake news” coming from what are considered to be extremists of one kind or another, Romer, in 2016, is calling the fundamental mathematical models of the economic theories that run much of our world “Post Real”.

The bitter irony is that while it is fiscal conservatism and neoclassical economics and neoliberal policies that are responsible for our collective crisis, it is liberal democracy that is being blamed for it, and consumed by the popular rage and discontent.

In many parts of the world, it is clear that we are at on the cusp of a revolutionary moment. Economic insecurity and crisis, disasters, the pandemic, war. The misery, frustration and anger is real. And the reason our indicators don’t pick them up is because neoclassical economics doesn’t consider important enough to measure, like personal debt and income distribution.

Part of what is so unsettling about the current moment is that the populist rage is defined so much by hate of the other, that it’s unclear what anyone’s goals or solutions are. One thing, however, is that part of what defines the extreme left and the extreme right today, as separate from centrists, liberal and social democrats, is that the extreme left and extreme right are both in denial about their matching moral hypocrisy.

They turn a blind eye to crimes among their own they condemn in others. And that’s what makes their extremism such a terrifying prospect: from the standpoint of administering justice: they are already fundamentally corrupt.

This popular discontent is being seized on by hard right faux-populists looking to leverage this crisis so they can continue dismantling even more democratic institutions.

The current fundamental challenge in this age for centrists, liberals and social democrats, reality-based conservatives and indeed, everyone seeking to defend liberal democracy. We need to show that it can work, and work better than the alternative.

Governments need to deliver the relief that’s needed, and that starts with recognizing that fiscal conservatism and neoclassical economics need to be challenged, because they are breaking our economies and our democracies.