In 2005 Citigroup Saw Canada, the U.S. & UK as "Plutonomies" - Economies Where Only the Rich Mattered.

Their plan? Figure out how to make even more money from making the rich richer, and the poor poorer. Spoiler: Citigroup flamed out three years later.

20 years ago, in 2005, I was watching the nightly news when a report came on, saying that there were startling stats out in Canada. I have been trying to get a copy of it, but as I remember it, the anchor said that for Canadian households where there was just one income earner, they had seen no increase in their income for two decades - since 1985, and economists couldn’t explain why.

That news report is part of what started me researching what was driving inequality, and since then, it is has generally only gotten worse. The concentration of wealth and income keeps getting greater, with more and more of the world’s ownership of almost everything in the hands of a smaller and smaller group. I spent years reading newspaper articles, papers, books, and piecing together the mechanics, strategies and justifications for various policies.

As it turns out, the entire thing was being explained in reports by Citigroup - a report “Plutonomy: Buying Luxury, Explaining Global Imbalances” which explains that the US and Canada are already Plutonomies, with so much wealth and income concentrated at the top, that there was no point in bothering with the small fry anymore. Instead, the paper set out to explain how investors could make money by pursuing policies to keep amplifying inequality.

It turns out that I was correct in my analysis about the fact that the majority of people are being written off as irrelevant, as well as why, expressed by Citigroup.

I’ll include as much of it as I can in this email - and you can read the whole pdf here.

Now, if you’re looking for some kind of morality in this tale, you should know Citigroup and its leaders managed to create the conditions for the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. They had lobbied for the 1990s-era repeal of the New Deal Era Glass-Steagal Act, which kept commercial banks and investment banks separate.

The “Plutonomy” is a study in Icarean Hubris. In the Global Financial Crisis, Citigroup crashed and received more in bailout money than it was worth;

“The U.S. Treasury extended a $45-billion credit line, and gave it a guarantee for $300 billion in "trouble assets" junk mortgages whose market price had fallen by 60 to 80 percent. Thic actions saved the bank and its bondholders, but Citigroup stock plunged belov a dollar by March 2009 as its equity value fell by more than 90 percent, to just $20 billion compared to $244 billion in 2006.”

WELCOME TO THE PLUTONOMY MACHINE

In early September we wrote about the (ir)relevance of oil to equities and introduced the idea that the U.S.is a Plutonomy - a concept that generated great interest from our clients. As global strategists, this got us thinking about how to buy stocks based on this plutonomy thesis, and the subsequent thesis that it will gather strength and amass breadth. In researching this idea on a global level and looking for stock ideas we also chanced upon some interesting big picture implications. This process manifested itself with our own provocative thesis: that the so called "global imbalances" that worry so many of our equity clients who may subsequently put a lower multiple on equities due to these imbalances, is not as dangerous and hostile as one might think. Our economics team led by Lewis Alexander researches and writes about these issues regularly and they are the experts. But as we went about our business of finding stock ideas for our clients, we thought it important to highlight this provocative macro thesis that emerged, and if correct, could have major implications in terms of how equity investors assess the risk embedded in equity markets. Sometimes kicking the tires can tell you a lot about the car-business.

Well, here goes. Little of this note should tally with conventional thinking. Indeed, traditional thinking is likely to have issues with most of it. We will posit that: 1) the world is dividing into two blocs - the plutonomies, where economic growth is powered by and largely consumed by the wealthy few, and the rest. Plutonomies have occurred before in sixteenth century Spain, in seventeenth century Holland, the Gilded Age and the Roaring Twenties in the U.S. What are the common drivers of Plutonomy?

Disruptive technology-driven productivity gains, creative financial innovation, capitalist-friendly cooperative governments, an international dimension of immigrants and overseas conquests invigorating wealth creation, the rule of law, and patenting inventions. Often these wealth waves involve great complexity, exploited best by the rich and educated of the time.

We project that the plutonomies (the U.S., UK, and Canada) will likely see even more income inequality, disproportionately feeding off a further rise in the profit share in their economies, capitalist-friendly governments, more technology-driven productivity, and globalization.

Most "Global Imbalances" (high current account deficits and low savings rates, high consumer debt levels in the Anglo-Saxon world, etc) that continue to (unprofitably) preoccupy the world's intelligentsia look a lot less threatening when examined through the prism of plutonomy. The risk premium on equities that might derive from the dyspeptic "global imbalance" school is unwarranted - the earth is not going to be shaken off its axis, and sucked into the cosmos by these "imbalances". The earth is being held up by the muscular arms of its entrepreneur-plutocrats, like it, or not.

Fixing these "global imbalances" that many pundits fret about requires time travel to change relative fertility rates in the U.S. versus Japan and Continental Europe. Why?

There is compelling evidence that a key driver of current account imbalances is demographic differences between regions. Clearly, this is tough. Or, it would require making the income distribution in the Anglo-Saxon plutonomies (the U.S., UK, and Canada) less skewed to the rich, and relatively egalitarian Europe and Japan to suddenly embrace income inequality. Both moves would involve revolutionary tectonic shifts in politics and society. Note that we have not taken recourse to the conventional curatives of global rebalance - the dollar needs to drop, either abruptly, or smoothly, the Chinese need to revalue, the Europeans/Japanese need to pump domestic demand, etc. These have merit, but, in our opinion, miss the key driver of imbalances - the select plutonomy of a few nations, the equality of others. Indeed, it is the "unequal inequality", or the imbalances in inequality across nations that corresponds with the "global imbalances" that so worry some of the smartest people we know.

4) In a plutonomy there is no such animal as "the U.S. consumer" or "the UK consumer", or indeed the "Russian consumer". There are rich consumers, few in number, but disproportionate in the gigantic slice of income and consumption they take.

There are the rest, the "non-rich", the multitudinous many, but only accounting for surprisingly small bites of the national pie. Consensus analyses that do not tease out the profound impact of the plutonomy on spending power, debt loads, savings rates (and hence current account deficits), oil price impacts etc, i.e., focus on the "average" consumer are flawed from the start. It is easy to drown in a lake with an average depth of 4 feet, if one steps into its deeper extremes. Since consumption accounts for 65% of the world economy, and consumer staples and discretionary sectors for 19.8% of the MSCI AC World Index, understanding how the plutonomy impacts consumption is key for equity market participants.

5) Since we think the plutonomy is here, is going to get stronger, its membership swelling from globalized enclaves in the emerging world, we think a "plutonomy basket" of stocks should continue do well. These toys for the wealthy have pricing power, and staying power. They are Giffen goods, more desirable and demanded the more expensive they are.

RIDING THE GRAVY TRAIN - WHERE ARE THE PLUTONOMIES?

The U.S., UK, and Canada are world leaders in plutonomy. (While data quality in this field can be dated in emerging markets, and less than ideal in developed markets, we have done our best to source information from the most reliable and credible government and academic sources. There is an extensive bibliography at the end of this note). Countries and regions that are not plutonomies: Scandinavia, France, Germany, other continental Europe (except Italy), and Japan.

THE UNITED STATES PLUTONOMY - THE GILDED AGE, THE ROARING TWENTIES, AND THE NEW MANAGERIAL ARISTOCRACY

Let's dive into some of the details. As Figure 1 shows the top 1% of households in the U.S., (about 1 million households) accounted for about 20% of overall U.S. income in 2000, slightly smaller than the share of income of the bottom 60% of households put together. That's about 1 million households compared with 60 million households, both with similar slices of the income pie! Clearly, the analysis of the top 1% of U.S. households is paramount. The usual analysis of the "average" U.S. consumer is flawed from the start. To continue with the U.S., the top 1% of households also account for 33% of net worth, greater than the bottom 90% of households put together. It gets better (or worse, depending on your political stripe) - the top 1% of households account for 40% of financial net worth, more than the bottom 95% of households put together. This is data for 2000, from the Survey of Consumer Finances (and adjusted by academic Edward Wolff). Since 2000 was the peak year in equities, and the top 1% of households have a lot more equities in their net worth than the rest of the population who tend to have more real estate, these data might exaggerate the U.S. plutonomy a wee bit.

Was the U.S. always a plutonomy - powered by the wealthy, who aggrandized larger chunks of the economy to themselves? Not really. For those interested in the details, we recommend "Wealth and Democracy: A Political History of the American Rich" by Kevin Phillips, Broadway Books, 2002.

We will focus here on data from Prof. Emmanuel Saez of U.C. Berkeley who works with data from tax sources. Figure 2 shows the share of income for the top 0.1%, 1% and 5% in the U.S. since the 1910s. Clearly the fortunes of the top 0.1% fluctuate the most.

Indeed, the fortunes of the top 5% (or even top 10%), or the top 1%, are almost entirely driven by the fortunes of the top 0.1% (roughly 100,000 households).

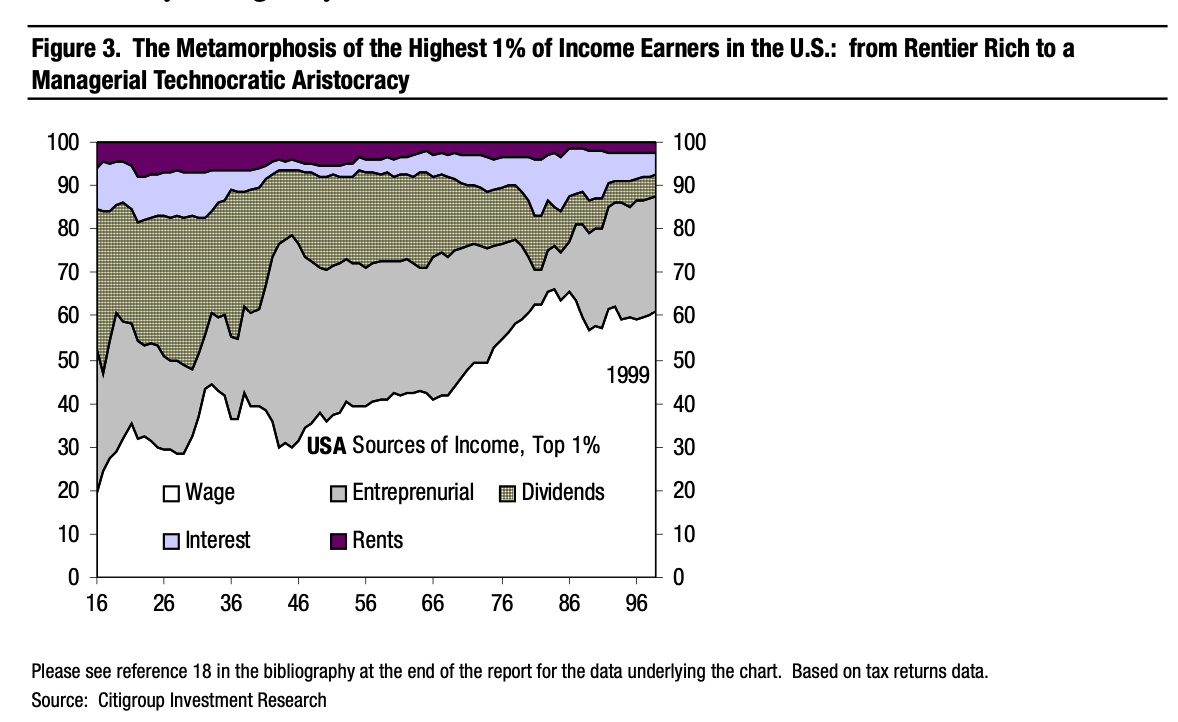

With the exception of the boom in the Roaring 1920s, this super-rich group kept losing out its share of incomes in WWI, the Great Depression and WWII, and till the early eighties. Why? The answers are unclear, but the massive loss of capital income (dividend, rents, interest income, but not capital gains) from progressive corporate and estate taxation is a possible candidate. The rise in their share since the mid-eighties might be related to the reduction in corporate and income taxes. Also, to a new wave of entrepreneurs and managers earning disproportionate incomes as they drove and participated in the ongoing technology boom. As Figure 3 shows, while in the early 20"h century capital income was the big chunk for the top 0.1% of households, the resurgence in their fortunes since the mid-eighties was mainly from oversized salaries. The rich in the U.S. went from coupon-clipping, dividend-receiving rentiers to a Managerial Aristocracy indulged by their shareholders.

EGALITARIAN JAPAN, CONTINENTAL EUROPE AND THE PLUTONOMIES OF CANADA AND THE UK

How did the Plutonomy fare in other countries over time? As Figures 4 and 5 show, the UK and Canada, pretty much follow the U.S. script. Japan, France, and the Netherlands are a bit different.

These were all plutonomies before the Great Depression, but the War, taxation, and new post-War institutional structures generated much more egalitarian societies, that hold even today. Only Switzerland remained unchanged. Neutrality through the wars saw its capital preserved, the lack of a progressive income and wealth tax regime, and low taxes helped.

PLUTONOMY WAVES - TECHNOLOGY, IMMIGRATION, FINANCE, COMPLEXITY (AND DOPAMINE) DRIVEN?

The reasons why some societies generate plutonomies and others don't are somewhat opaque, and we'll let the sociologists and economists continue debating this one. Kevin Phillips in his masterly "Wealth and Democracy" argues that a few common factors seem to support "wealth waves" - a fascination with technology (an Anglo-Saxon thing according to him), the role of creative finance, a cooperative government, an international dimension of immigrants and overseas conquests invigorating wealth creation, the rule of law, and patenting inventions. Often these wealth waves involve great complexity.

"One explanation of ...increasing polarization of wealth comes from considering these great transformations as surges of complexity - waves of economic, political and commercial change - profound enough to break down old vocational and price relationships, greatly favoring persons with position, capital, skills, and education" (page 259, author's emphasis).

Clearly, a speculative instinct is key to generating and sustaining these complex and risky transformations. Here, a new, rather out-of-the box hypothesis suggests that dopamine differentials can explain differences in risk-taking between societies. John Mauldin, the author of "Bulls-Eye Investing" in an email last month cited this work.

The thesis: Dopamine, a pleasure-inducing brain chemical, is linked with curiosity, adventure, entrepreneurship, and helps drive results in uncertain environments.

Populations generally have about 2% of their members with high enough dopamine levels with the curiosity to emigrate. Ergo, immigrant nations like the U.S. and Canada, and increasingly the UK, have high dopamine-intensity populations. If encouraged to keep the rewards of their high dopamine-induced risk-seeking entrepreneurialism, these countries will be more prone to wealth waves, unequally distributed. Presto, a plutonomy driven by dopamine!

[NOTE: This is idiotic, and is a perfect example of people who are supposed to be experts in economics and money ignoring the role of their own industry - finance and debt - with an ex-post-facto explanation based in neuroscience and chemistry, in which they have zero competence.

As I have written many times, the divergence in incomes and inequality is the result of the intellectual coup faced by economics and democracy in the 1970s.]

Interesting that Kevin Phillips also mentioned the role of immigrants in driving great wealth waves (oblivious to the role of dopamine, though). He emphasizes the role of the in-migration of skilled and well-capitalized refugees and cosmopolitan elites in catalyzing wealth waves. Being the son of refugee parents from the India-Pakistan partition in 1947, and now a wandering global nomad, I can see this argument quite clearly. (Also, I need to get my dopamine level checked.) Phillips talks of the four great powers - Spain in the fifty years after 1492, the United Provinces (Holland) in the sixteenth century, seventeenth century England, and nineteenth century U.S., all benefiting from waves of immigrants, fleeing persecution, and nabbing opportunities in distant lands.

WHY THE PLUTONOMY WILL GET STRONGER WHERE IT EXISTS, PERHAPS ATTRACT NEW COUNTRIES

We posit that the drivers of plutonomy in the U.S. (the UK and Canada) are likely to strengthen, entrenching and buttressing plutonomy where it exists. The six drivers of the current plutonomy: 1) an ongoing technology/biotechnology revolution, 2) capitalist-friendly governments and tax regimes, 3) globalization that re-arranges global supply chains with mobile well-capitalized elites and immigrants, 4) greater financial complexity and innovation, 5) the rule of law, and 6) patent protection are all well ensconced in the U.S., the UK, and Canada. They are also gaining strength in the emerging world.

Eastern Europe is embracing many of these attributes, as are China, India, and Russia.

Even Continental Europe may succumb and be seduced by these drivers of plutonomy.

As we argued in the Global Investigator, "Earnings - Don't Worry, Capitalists Still on Top",

", June 10, 2005, the profit share of GDP is highly likely to keep rising to the highs seen in the 1950s/60s. New markets like China and India, their contribution to the global labor supply, the ongoing productivity revolution, the quasi-Bretton Woods system in the U.S. dollar bloc, and inflation-fighting central banks should all help.

However, a high profit share like in the 1950s/60s does not ensure plutonomy. Indeed, in the 1950s/60s, U.S. and other key countries did not see increasing income inequality.

Society and governments need to be amenable to disproportionately allow/encourage the few to retain that fatter profit share. The Managerial Aristocracy, like in the Gilded Age, the Roaring Twenties, and the thriving nineties, needs to commandeer a vast chunk of that rising profit share, either through capital income, or simply paying itself a lot. We think that despite the post-bubble angst against celebrity CEOs, the trend of cost-cutting balance sheet-improving CEOs might just give way to risk-seeking CEOs, re-leveraging, going for growth and expecting disproportionate compensation for it. It sounds quite unlikely, but that's why we think it is quite possible. Meanwhile Private Equity and LBO funds are filling the risk-seeking and re-leveraging void, expecting and realizing disproportionate remuneration for their skills.

THOSE SCARY "GLOBAL IMBALANCES" - REFLECT PLUTONOMY AND DEMOGRAPHY, QUITE LOGICAL AND UNTHREATENING

We have all heard the lament. A bearish guru, somber and serious, spelling out that the end is near if something is not done urgently about those really huge, nasty "Global Imbalances".

'. The U.S. savings rate is too low, the U.S. current account deficit is too

high, foreigners are not going to keep financing this unless compensated with higher interest rates, and a sharply lower U.S. dollar. The world, being so imbalanced, is about to tip over it's axis, all hell is going to break loose, so don't any equities - the risk premium is high reflecting these imbalances and is going to go higher (i.e., lower stock prices) when the earth finally does keel over.

A more balanced view acknowledges these nasty imbalances, but predicts a gentle, gradual dollar decline, a yuan revaluation, and the hope that Asians and European (ex-UK) consumers will embark on a spending journey, righting the world. A tough workout, but she'll be right.

Almost all the smart folks we know - our investors, our colleagues, our friends in academia, politicians believe in some variant of these two stories. There are very few exceptions who consider these "Global Imbalances" not scary but perfectly natural and rather harmless. (We can think of Gavekal as one of these exceptions, but their repose of comfort is different from ours - they have a new book out "The Brave New World" elucidating the new business model of global "Platform" companies, etc).

This prediction also proved to be massively incorrect. Four years later, Citigroup was insolvent, and 30 years later we have serious global instability, civil and political unrest.

Our point here is not to dismiss the conventional views as outright wrong. However, we offer a competing view and, in some instance, a view that is complementary to the conventional explanation. Our view, if right, suggests that applying an excessive risk premium to "Global Imbalances" is a flawed approach to equity investing. Note that our house view, for instance, sees no cataclysmic collapse in the dollar. The U.S. current account deficit is anticipated to remain flat at 6.8% of GDP. The Japanese and the Euro surpluses are expected to continue. A plutonomy world is not inconsistent with these forecasts.

First a quick glance at these Global imbalances. Figure 12 shows the current account balances for plutonomies (the U.S., UK, and Canada) and the others - continental Europe and Japan. We have left out China and other emerging markets because we do not have their income inequality data, although they are definitely an important part of the "Global Imbalance" story.

Well, it seems that the plutonomies (the U.S., UK, and Canada together) have deteriorating current account balances; the others are running a combined current account surplus.

Current account balances are driven by three possible sources - the net savings of the government, the corporate sector and the household sector. Figure 13 shows our bottom-up estimates for corporate free cash flow/sales, a close cousin of corporate savings - these look similarly good across the world, both for plutonomies and the others. We won't pursue this avenue as a key driver of today's

How about government deficits? Well, they seem to be equally bad in the U.S., UK,

Continental Europe, and very bad in Japan. Hmm. We’ll leave this one alone too.

We need to focus on the household sector (the consumer in simple English) as the key driver of those current account imbalances that so worry the equity bears. Indeed, Figure 14 shows the gap between the households sector's savings rate for the plutonomies (U.S., UK, and Canada) less those of continental Europe and Japan. This gap is large and moves with the gap in the current accounts of these two blocs.

Our contention is simple - while the drivers of savings rates in countries are many - we focus on plutonomy as a key new explanation for different savings rates in different countries. (As an aside, considerable empirical research shows that the external imbalances between the U.S., Europe, and Japan are driven by demography. The U.S. is just younger than Japan, driving household savings differences that drive those current account differences. This topic is beyond the scope of our story here. For those interested, check out "Capital Flows Among the G-7 Nations: A Demographic Perspective", Michael Feroli, U.S. Federal Reserve Board, October 2003).

Our contention: when the top, say 1% of households in a country see their share of income rise sharply, i.e., a plutonomy emerges, this is often in times of frenetic technology/financial innovation driven wealth waves, accompanied by asset booms, equity and/or property. Feeling wealthier, the rich decide to consume a part of their capital gains right away. In other words, they save less from their income, the well-known wealth effect. The key point though is that this new lower savings rate is applied to their newer massive income. Remember they got a much bigger chunk of the economy, that's how it became a plutonomy. The consequent decline in absolute savings for them (and the country) is huge when this happens. They just account for too large a part of the national economy; even a small fall in their savings rate overwhelms the decisions of all the rest. Figure 15 provides a simple example of how this happens.

There is proof that high income earners, who saw their share of income go up in the U.S. in the nineties, and enjoyed the equity boom, reduced their savings rate as in our example. Indeed, in the real world, it went negative! Since that reduced savings rate was applied to their new enlarged chunk of income, sure enough the total savings rate fell sharply.

Dean Maki and Michael Palumbo, wrote the paper (at Alan Greenspan's suggestion) that demonstrated this fall in the savings rate of the rich in response to the equity boom (See Maki and Palumbo, "Disentangling the Wealth Effect: A Cohort Analysis of Household Savings in the 1990s", April 2001). Figure 16 demonstrates the savings rates at different points for different income groups.) The very rich, the top 20%, had a savings rate of 8%, much higher than other less affluent groups in 1992. By 2000 this savings rate had gone from 8%- to -2%! The wealth effect at work. And then this reduced savings rate of the rich hit their huge incomes, swollen by the plutonomy, savaging the U.S.'s overall savings rate. This is our contribution to the debate. Plutonomy plus an asset boom equals a drop in the overall savings rate. (Asset booms by themselves, i.e., the wealth effect by itself does not do the trick, as we will show soon.)

Let's look at some of the coolest figures that amplify and verify this idea. Figure 17 plots the share of the top 1% of U.S. households since 1929. Our thesis is that the higher the share of income going to the top 1%, the lower the overall household savings rate (shown inverted in Figure 17). There is a pretty tight correlation between the two, despite the many other drivers of savings rates (demography, interest rates, financial deepening, retirement security, etc). The same information is shown in Figure 18, a scatter plot - when the rich take a very high share of overall income, the national household savings rate drops, and vice versa. In a plutonomy, the rich drop their savings rate, consume a larger fraction of their bloated, very large share of the economy. This behavior overshadows the decisions of everybody else. The behavior of the exceptionally rich drives the national numbers - the "appallingly low" overall savings rates, the "over-extended consumer", and the "unsustainable" current accounts that accompany this phenomenon. We want to spend little time worrying about these (non)issues, neither do we think they warrant any risk premium on equities. They simply reflect the reality of demographic differences between nations, and that some nations are plutonomies, while others are not. Unequal inequality among nations is mirrored in the logical imbalances between them.

Canada also confirms our thesis. A plutonomy begets a lower household savings rate.

See Figures 20 and 21. We have also attempted, in Figure 22, to put the relationship on a cross border-basis for the eight countries where we have comparable data. Again, plutonomies like the U.S., Canada, and the UK have lower household savings rates than the more egalitarian countries like France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Spain, and Japan.

One quick point - we asserted earlier that a plutonomy plus an asset boom corresponded with a decline in the household savings rate. It was not just the standard asset boom spawning a wealth effect and ergo higher consumer spending and a lower savings rate.

Is there as tight a relationship between asset prices and the savings rate as there is between income inequality and the savings rate (correlation -0.7) shown in Figure 17?

Well, in Figure 23 we plot the 10-year returns of the U.S. stock market with the household savings rate. While the relationship is tight in the great bull market between 1982-2000, the huge bull market in the 1950s and 1960s sees no real wealth effect. (The overall correlation of +0.19, i.e., low AND the wrong sign). Why? Among other sensible reasons we do not know, we think it was the absence of plutonomy in that period that kept the spending decisions of the rich, obviously enjoying solid equity gains, from dominating the overall numbers. They were just not disproportionately a big part of the economy then. That would have to wait for the A skeptic, while agreeing with our plutonomy thesis, may still not be convinced about the ability of households to sustain the low savings rate. Surely, even in the brave new world of plutonomies we describe, households cannot forever keep their savings rate low? We have two interesting dynamics in place that should prevent a sharp drop in consumption and so pushing the savings rate higher. One, the difference of the household's financial assets to disposable income (assets with value of housing stock excluded) and its liabilities to disposable income exceeds its historical average.

Households can afford to run down their assets to finance consumption for a while.

Please see Figure 24 we have borrowed from Lewis Alexander, our Chief Economist.

Now, I don’t have room to include the whole paper, which goes on to recommend a series of ultra-luxury brands for investment.

But one of the conclusions of the analysis is notable, including its dismissal of warnings that proved to be completely accurate.

Outlandish it may sound, but examined through the prism of plutonomy, some of the great mysteries of the economic world seem to look less mystifying. As we showed, there is a clear relationship between income inequality and low savings rates: the rich are happy to run low or negative savings given their growing pool of wealth. In turn, those countries with low/negative household savings rates tend to be the countries associated with current account deficits.

The “low savings” of Americans and other countries is distorted because of the “plutonomy” (or oligarchy). Just as most income and wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few, and everyone else has less, those wealthy few are saving less.

The entire, false, basis of trick-down, supply-side economics is that you have to save to invest. For people who already have vast collateral, this is the least true: they can borrow, and borrow at ultra-low rates that they can then use arbitrage to lend or invest in mortgages or real estate that have a higher interest rate.

The people who have the most money don’t save it. They don’t need to save it - they can borrow at the best rates.

The reality is that we are at a point where the concentration of wealth and income means it is stifling competition, and due to monopoly and oligopoly pricing, they can charge higher prices for their own goods while pressuring suppliers and workers for lower prices.

However, all of those “small-timers” are expected to keep taking on more and more personal debt to finance their home - whose mortgage was owned by a plutocrat. The system collapsed three years later and Citigroup - the largest bank in the U.S. - was bailed out.

We’re hearing similar, oblivious arguments now, because the current market mania is the result of a string of asset bubbles that have driven up the value of everything, and it is currently collapsing. These are the consequences of 17 years of total failure to address the crooked casino that comprise the U.S. and global financial sector. The small players lose everything, but the high-rollers get bailed out by the Casino, even when they lose.

The manic, out-of-control behaviour we are seeing in the streets and in government is the result of manic and out-of-control behaviour in the markets, much of which is just rapacious plundering and rip-offs which is being passed off as “GDP growth” or “investment” when it is usury, ponzi schemes and private actors charging people for access to their own property.

It’s a system where people can buy their way out of anything, which is to say, it is a system that is corrupt, and it needs to be de-corrupted.

The seriousness of how bad it is should not be understated, but the idea that radical ideas that involve “burning down” the system - whether they are libertarians who want to dismantle government, or socialists or communists who want to dismantle capitalism, the idea that the problem will be solved if opponents are crushed is an ideology that is doomed to eternal conflict.

What’s required is a return to the rule of law. We need to break up companies and increase competition. We need to provide access to capital for companies to start up and scale up. We need to restructure the unjust personal debt that people have been forced to take on as a result of paying for everyone else’s mistakes.

A colossal amount of the rage and powerlessness in countries like Canada, the UK and the US, which Citigroup gleefully described as plutonomies, is due to these plutonomies hijacking everything for their own interest.

Many individuals feel powerless, because they have been rendered powerless by an economy - and by banks like Citigroup - who consider them irrelevant and disposable.

It is perfectly legitimate, free and democratic for citizens to assert that their rights not be undermined by private interests.

In 1938, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivered an address to Congress on the threat of concentrated private power:

Unhappy events abroad have retaught us two simple truths about the liberty of a democratic people.

The first truth is that the liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than their democratic state itself. That, in its essence, is Fascism—ownership of Government by an individual, by a group, or by any other controlling private power.

The second truth is that the liberty of a democracy is not safe if its business system does not provide employment and produce and distribute goods in such a way as to sustain an acceptable standard of living.

Both lessons hit home.

They certainly do. The problem is that instead of fixing the game so it works, everyone just wants to figure out how to make more money from it.

30-

DFL