How Kingdoms Are Lost: All For Want of a Horseshoe Nail

Understanding how risk builds up, how it's managed, and how we're blind to it.

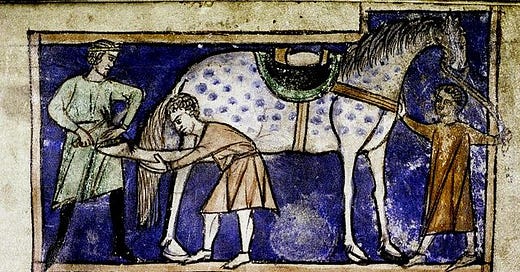

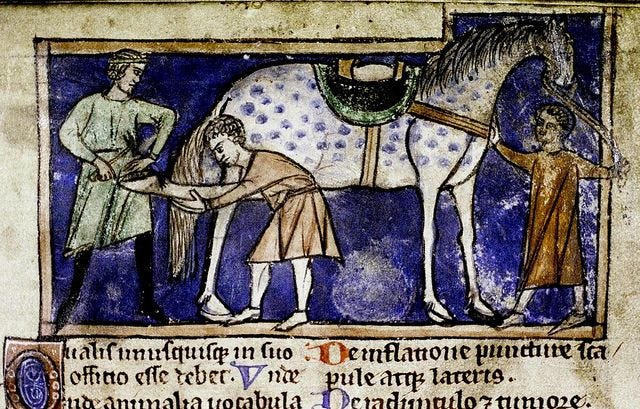

For Want of a Nail

For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the message was lost.

For want of a message the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

Variations on the proverb “For Want of a Nail” have been around for at least 800 years. When we think of causation we think like physicists. Newton said that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction, so we think that there is a sense of proportion between an event and the thing that caused it. Or we may (without realizing it) think of it in terms of thermodynamics: some of the energy you use in doing any action will be lost, so it might take even more effort to cause an event.

The story of a single missing nail leading to the downfall of a kingdom doesn't follow the rules of causation. A nail didn’t cause the kingdom to be lost: a missing nail did.

Something not being there caused the problem. How can you measure that? How do you count all the things that aren’t there?

The horseshoe nail example is not a story of one to one causation as it is of risk transmission. Plenty of people fail to understand risk, and how a small risk can grow into a large one. At the same time, we need to be able to tell the difference between real threats and mock ones.

A lot of conspiratorial thinking gets this wrong, because conspiracy theories are based on making assumptions about the way the world works, and when proven wrong, insisting that the evidence is wrong, not the theory.

How could someone weak beat someone strong? There is an assumption that only a Goliath could beat a Goliath. How could a nobody with no social stature, like Lee Harvey Oswald, kill John F. Kennedy, the most powerful man in the world? Because being president didn’t make Kennedy invulnerable to a gunshot, and guns are social levellers.

There are plenty of experts who have made mistakes and miscalculations, whether they are engineers or economists, because they fail to see the way small risks can become big ones in systems under extreme stress.

The same blindspot has also been behind many engineering disasters.

When the Challenger shuttle exploded, it was because rubber O-rings that helped seal solid fuel rockets became too stiff when overnight temperatures at the launch pad got close to freezing.

Richard Feynmann, the physicist who sat on the Challenger inquiry, demonstrated the problem during a press conference by dipping an O-ring in his ice water and showing it was stiffer when it was cold. As a result, instead of filling the gap that sealed fuel into a rocket, it leaked.

A later space shuttle disaster was caused by a suitcase-sized piece of foam breaking off the fuel tank and hitting the shuttle’s wing. Many at NASA couldn’t see how a piece of foam — which after all was very light and insubstantial — could pose a threat to the hard leading edge of the wing. The answer is that the folks at NASA - of all people, hadn’t done their basic physics: at a high enough speed — with enough added energy — the foam had enough mass to punch through the wing, as they discovered to their shock and dismay when they tested it.

The idea of a tiny vulnerability that can be exploited against all odds is very common in stories, going back to Achilles’ heel. The legend holds that Achilles mother held him by his heel and dipped him in the River Styx to protect him. The only part left untouched was his weak point. So it goes with knights who have a chink in their armour, dragons who have a soft underbelly. The legendary and mythic status of the a tiny flaw can be exploited for gain — its popularity in and persistence storytelling — is an indication of the fundamental importance we attach to it. It is anchored in myth and legend because we had no science to explain it.

Real world risk, legendary risk

Information systems and human institutions need energy to run all the time, which can make them like a structure that is being stressed.

There is a useful and scientific way of thinking about risk transmission that has been developed in structural engineering: the propagation of cracks in structures, especially structures under load. This is obviously important when it comes to designing and building anything: dams, bridges, roads, buildings, ships, cars, trains and planes. All have to last for a long time, endure shifting conditions and different loads without failure, because failure puts lives at risk. Vehicles also need to be efficient: they need to run on a minimum of fuel, but they also have to be light but strong. Ships and planes need to be safe, but they also need to float and fly.

In engineering structures, the entire system may be subject to different loads. Imagine a steel ship in heavy seas, being pushed, pulled and twisted as its bow and stern are lifted by the crest of two waves while its middle sags between, or an airplane being buffeted by high winds.

When an entire system is under stress, it is possible for pressure to build up and be concentrated to an incredible degree is a single location. In the instance of the S.S. Schenectady, a crack that started at the edge of a square hole in a steel deck propagated to the hull and the ship split in two. One of the reasons metal ships and aeroplanes have rounded corners instead of square ones on their doors or windows is that it spreads out the stress around the entire curve, instead of concentrating it at a point.

In mechanical engineering, cracks can be halted by dislocations, which can be a barrier, or it can also be a point where weak points are offset. In a brick wall, bricks aren’t just stacked one on top of the other, they are overlaid so the end of bricks in the row above are above the middle of bricks below and above. Even piling bricks in this way without mortar makes them more stable.

The toughest materials are the ones that combine strength and flexibility: composite materials like fibreglass and Kevlar where individual fibres of tremendous strength are held in place by a common medium. Take a diamond chisel and hit a carbon fibre composite with the same energy you would apply to a diamond and it wouldn’t even make a dent. Individual fibres may break, but the crack can’t travel. The point is illustrated by the difference between a steel bar and a stranded steel cable of the same diameter. The steel bar is inflexible and can break clean through under a heavy enough load, while the cable is flexible and individual strands can break without the cable as a whole failing.

In physical systems, how stresses work and cracks propagate can be counterintuitive, even for engineers. J. E. Gordon writes:

“Whatever the scale, the practical importance of stress concentrations is enormous. The idea which Inglis expounded is that any hole or sharp re-entrant in a material causes the stress in that material to be increased locally. The increase in local stress, which can be calculated, depends solely upon the shape of the hole and has nothing to do with its size. All engineers know about stress concentrations but a good many don’t in their hearts believe in them since it is a clearly contrary to common sense that a tiny hole should weaken a material just as much as a great big one. The root cause of the Comet aircraft disasters was a rivet hole perhaps an eighth of an inch in diameter.”

(The DeHavilland Comet had three planes break up in mid-air and was subject to a major safety investigation in the 1950s).

One of the reasons that this kind of modelling is useful — and important — is that economic models are based on large-scale averages. They treat the economy like the pressure inside a balloon or a tire — and not as a system that has different pressures, structures, densities, weaknesses and stresses.

Risk and Markets

The idea of concentrations of stress in a system turning into catastrophic failure, starting at the weakest point, have real-life corollaries in the markets.

Number 3 on Mandelbrot’s list of Ten Heresies of Finance is:

“Market “timing” matters greatly. Big gains and losses concentrate into small packages of time.”

“In a financial market, volatility is concentrated ... and it is no mystery why. News events — corporate earnings releases, inflation reports, central bank pronouncements — help drive prices. Orthodox economists often model them as a long series of random events spread out over time ... their assumed distribution follows the bell curve so no single one is preeminent... From 1986 to 2003, the dollar traced a long, bumpy descent against the Japanese yen. But nearly half that decline occurred on just ten out of those 4,695 trading days. Put another way, 46 percent of the damage to dollar investors happened on 0.21 percent of the days. Similar statistics apply in other markets. In the 1980s, fully 40 percent of the positive returns from the Standard & Poor’s 500 index came during ten days — about 0.5 percent of the time.”

That doesn’t mean we don’t know, or can’t know anything. Our black and white thinking means we think if we don’t have total control, we have no control, when the fact of the matter is that we have some control. We can reduce the impact of a risk with accumulated surplus and accumulated knowledge.

Hayek’s major critique of Keynes was that he was missing information: but we will always be missing information: there is always some uncertainty, which is something Keynes acknowledged. That is an inescapable fact of the universe. Risk may be unavoidable, but that does not mean it has to be devastating when the unexpected happens. It does not mean we are helpless, or that we know nothing: it’s just that we don’t know everything. That is why we have strategies: we take risks (calculated or not), have back-up plans and failsafes.

Financial risk

This idea of real-world risk being like crack that starts small and grows ever-bigger is not just a metaphor. A crack can be stopped when it reaches a barrier.

In economic and political terms, opening up free trade zones and giving up sovereign control over currency comes with a risk: you get access to new markets and the risks that come with them.

If a country has its own currency and is going through bad economic times, it can react by changing exchange rates and the value of its currency relative to its neighbours and trading partners.

The barrier (a currency exchange) allows a jurisdiction with control over its own currency and interest rates to react in response to the shock.

The Eurozone crisis - when countries were at risk of defaulting - is a story of risk transmission. The EU extended the use of its common currency, the Euro, with the hope of finding new markets for its products.

Germany in particular benefited — much of its improved financial position in the 2000s was due to sales to countries like Greece, where people were spending freely thanks to much lower interest rates on debt they were enjoying. The EU was blind to the risk of Greece, in part because the books had been cooked to conceal that the country’s finances were in worse shape than anyone thought, but also because lenders made terrible loans.

Joseph Stiglitz writes:

“Changes in exchange rates and interest rates are critical for helping economies adjust. If all the European countries were buffeted by the same shocks, then a single adjustment of the exchange rate would do for all. But different European economies are buffeted by markedly different shocks. The euro had taken away two adjustment mechanisms, and put nothing in its place... Looking across Europe, among the countries that are doing best are Sweden and Norway, with their strong welfare states and large governments, but they chose not to join the euro. Britain is not in crisis, though its economy is in a slump: it too chose not to join the euro, but it too decided to follow the austerity program.”

The countries that were spared were the ones whose non-membership in the Euro effectively prevented the transmission of risk across their borders.

The difference is between an iron bar and a braided steel rope under stress: a crack in the monolithic iron bar means it will snap in half suddenly, while individual strands is the cracks in the steel rope get stopped.

If the individual countries in crisis each had their own currency, they could react to adapt to local conditions. Instead they are in an even worse position: getting rid of the Euro for Greece or another one of the countries means substituting something that at least has an agreed-upon value with a currency that starts out as totally worthless: they are in a trap.

There are other kinds of risk related to other currency crises throughout the 1990s. The ease with which capital can flow in and out of countries can make markets very volatile. Some of the countries that were spared the crisis in the 1990s were ones that required a hold or a time period on foreign investment. This of course, requires regulation.

Too big to fail

The phrase “too big to fail” is ambiguous: it seems as if it means “this thing is so big that it couldn’t possibly fail” when it really means “this thing is so big that it can’t possibly be allowed to fail.” The double meaning is a little like the old Saturday Night Live sketch where a retiring engineer tells his colleagues “You can’t put too much water in a nuclear reactor,” then leaves. His young colleagues don’t know whether they should put water into the reactor or not. (It explodes).

The idea that the banks that required taxpayer bailouts after 2008 were “too big to fail” because the knock-on consequences of failure would be disastrous. The risks were contained, at incredible cost, but nothing since then has been done to further reduce them. Most investigations have resulted in fines and no admission of wrongdoing, even when the fine was in the billions of dollars. Banks could have been broken up into a series of smaller banks, so that the risk of any one failure could be contained, but that has not happened.

Even more troubling, actual criminal activity is going unpunished. HSBC was convicted of money laundering with Mexican drug cartels and terrorist organizations. HSBC had $19.7 billion in dealings with Iran, shipped $7-billion out of Mexico to the U.S., and broke rules to carry on business with Iran, Burma and North Korea. They were fined $2-billion — one month worth of profits — but no one was convicted because a conviction could trigger a clause that would prohibit dealings with the U.S. government. That punishment — for money laundering for drug cartels and terrorists — was deemed too severe.

In June 2013, Bloomberg reported that “traders at some of the world’s biggest banks manipulated benchmark foreign exchange rates used to set the value of trillions of dollars worth of investments.” It is a market that sees “$4.7-trillion in trades a day, and is one of the least regulated.”

Banks were found to be manipulating the “LIBOR” (the London-Interbank Offered Interest Rate), which is a global interest rate — “the most important figure in finance,” according to The Economist, which referred to the scandal as “the rotten heart of finance.” “It is used as a benchmark to set payments on about $800 trillion-worth of financial instruments, ranging from complex interest-rate derivatives to simple mortgages. The number determines the global flow of billions of dollars each year.”

Traders and banks in London were found to be manipulating it for their own interest, rather than setting the rates according to the actual market. Among other problems, this triggered a $4-billion payout by U.S. municipal governments in “interest-rate swaps,” but The Economist suggested manipulations of LIBOR had been happening since the late 1980s.

We have rules to stop people from doing dangerous and stupid things. We put locks on our reinforced doors. We have regulations and barriers to slow things down. We quarantine people with contagious diseases. We reinforce doors and build strong locks to keep intruders out.

Many of the reasons for disagreeing with libertarian arguments about people being “free to choose” — the legalization of all drugs for example — is that they aren’t accounting for the transmission of risk. Addiction, whether to alcohol or drugs, is can destroy not just the lives of the addict, but is incredibly disruptive, destructive, painful and costly to the people around them. The effects of addiction to a family can be like a freight train derailing at high speed through a community.

The concepts of risk, opportunity, and chance are all closely linked. We all understand “nothing ventured, nothing gained.” We all know that there are activities that are low-risk and low reward. We know that everything has a cost. But when it actually comes to seizing an opportunity, the potential gains from the reward may blind us from the risk involved — or it may be hidden.

For example, the rationale behind creating mortgage-backed securities — buying millions of mortgages from banks, treating them as if they were shares from a company, and selling them to investors around the world — is that the housing market in the U.S. always went up, and was therefore safe (this was not true). That is just one example of a “financial innovation” — derivatives, credit default swaps, and the strategy followed by Long Term Capital, all of which were designed to minimize risk, but did just the opposite.

In Liar’s Poker, Michael Lewis described his time at Salomon Brothers, which had been a staid bond trading company that ended up playing a key role in the Savings & Loans scandal. Lewis himself became “the biggest swinging dick” on Wall Street.

The Garn St. Germain Act of 1982 allowed Savings and Loans to reduce the amount their total deposits on hand. This money is usually kept in reserve to protect institutions from a bank run, or a downturn. It’s a buffer against bad times. Lowering the amount they had to keep on hand freed up money, which Wall Street invested and promptly lost. S & Ls started to go broke. Over 700 failed and had to be bailed out at taxpayer expense. Another reason for struggling S & Ls? The federal reserve’s focus on fighting inflation, and the collapse in real estate prices in Texas and elsewhere due to falling oil prices.

The 2008 financial meltdown was, in part, because someone somewhere thought it would be a good idea to make people’s mortgages a Wall Street investment. The 1929 stock market crash was also driven partly by real estate speculation in Florida. Property in the southern U.S. has been involved in stock market bubbles and devastating crashes dating back to the Mississippi Scheme in France of 1720.

What do these things have in common? One obvious answer is real estate: but really, its about the transmission of risk, from one area of the economy which is risky and speculative — financial markets — to areas of the economy that generally aren’t, like owning a home or property. They are mixing markets, from one which is low-risk and low-return, which spreads income widely, to one which is high-risk, and high-return for a tiny few, wiping everyone else out.

There used to be rules that kept investment and retail banks separate in the U.S.: the Glass-Steagall Act (or parts of it) that stood from 1933 until 1996, when it was repealed under the Clinton administration because it was “no longer needed.”

One of the ideas of promoting home ownership (as opposed to renting) is that it provides people with a way to build up their personal wealth. You can spend your entire life renting, and die owning nothing, or you can spend your life paying off a mortgage and die leaving a house worth something. Turning people’s mortgages, which are supposed to be stable and safe into something that can be bought and sold in the millions, and steeply devalued in minutes by investors in another country looking to minimize their losses is a bad idea.

In another part of his Ten Heresies of Finance, Benoit Mandelbrot writes:

“[Experts] assume that “average” stock-market profit means something to a real person; in fact, it is the extremes of profit or loss that matter most. Just one out-of-the-average year of losing more than a third of capital — as happened with many stocks in 2002 — would justifiably scare even the boldest investors away for a long while. The problem also assumes wrongly that the bell curve is a realistic yardstick for measuring risk. As I have said often, real prices gyrate much more wildly than the Gaussian standards assume... Real investors know better than the economists. They instinctively realize that the market is very, very risky, riskier than the standard models say. So, to compensate for taking that risk, they naturally demand and often get a higher return.”

Experts make many mistakes thinking that markets are more regular than they are. Later in the same chapter, Mandelbrot writes that an IBM colleague asked him about a “some MIT professor [who] had found a systematic way to beat the stock market.”

The professor in question was Stanley S. Alexander, and his formula was:

“Every time the market rises by 5 per cent or more, buy and hold. When it falls back 5 per cent, go short and hang on... He calculated that an investor who had blindly followed such a rule from 1929 to 1959 would have gained an average 36.8 per cent a year, before commission.” Mandelbrot wrote Alexander a letter asking “Which of several possible prices, specifically, had he used in calculations?” to which the reply was a dismissive, “It doesn’t make any difference.””

As Mandelbrot notes, it did:

“It made the difference between a 36.8 per cent profit and a loss of as much as 90 percent of the investor’s capital...Alexander had [used] daily closing prices... The real world clipped his profits on the way up and stretched his profits on the way down.”

There are other ways in which we overreact to threats, or are blind to warning signals, because we have been told by theory and dogma, that we are told we are safer than we are.

DFL

Todd Rundgren used "For The Want Of A Nail" as the basis for an exceptional song he recorded with Bobby Womack. It really got the proverb's message across.