If MMT is wrong, why is it so much better at predicting the economy - and economic disaster?

The reason we’re in crisis is not because policymakers have been ignoring the advice of orthodox economists, but because they have been following it.

In 2016, Paul Romer, who was then Chief Economist at the World Bank wrote “The Trouble with Macroeconomics” in which he eviscerated the current state of macroeconomics in the U.S. and around the world, writing that orthodox macroeconomics had been in “30 years of intellectual regress,” and was so disconnected from reality that it was “post-real”. Romer wrote his paper, inspired by a similar critique of “string theory” in physics.

Lee Smolin begins The Trouble with Physics (Smolin 2007) by noting that his career spanned the only quarter-century in the history of physics when the field made no progress on its core problems. The trouble with macroeconomics is worse. I have observed more than three decades of intellectual regress. [Emphasis mine]

The reason for this, Romer argues, is that orthodox economics - the formulas used by government budget offices, political parties, central banks and business, are based on a series of assumptions that are not backed up by facts.

They are, in fact, filled with assumptions that are a figment of a shared imagination:

In the 1960s and early 1970s, many macroeconomists were cavalier about the identification problem.

The identification problem is the question of identifying whether one thing is causing the other. When different arrangements can all end up with the same result, you can end up oversimplifying and attributing too much influence to one factor.

Romer continues:

They did not recognize how difficult it is to make reliable inferences about causality from observations on variables that are part of a simultaneous system. By the late 1970s, macroeconomists understood how serious this issue is, but as Canova and Sala (2009) signal with the title of a recent paper, we are now “Back to Square One.” Macro models now use incredible identifying assumptions to reach bewildering conclusions. To appreciate how strange these conclusions can be, consider this observation, from a paper published in 2010, by a leading macroeconomist:

... although in the interest of disclosure, I must admit that I am myself less than totally convinced of the importance of money outside the case of large inflations.

Romer was suitably outraged, as we all should be, about an economist who isn’t convinced of the importance of money. He was also outraged by the fact that economists didn’t think that people’s actions mattered, and he was specific about it.

“Macroeconomists got comfortable with the idea that fluctuations in macroeconomic aggregates are caused by imaginary shocks, instead of actions that people take, after Kydland and Prescott (1982) launched the real business cycle (RBC) model.”

By this, Romer means that economists are inserting what he calls “facts of unknown truth value” which is to say, they are breezily assuming something and putting it into a mathematical formula.

And as a model, it has continually failed to predict crises and inflation that other “heterodox” models of the economy have succeeded in doing .

The Onion’s satire of the 1929 Wall Street Crash is not that far from the mark. It was driven by years of “easy money” under treasury secretary of Andrew Mellon, who was already phenomenally wealthy when he took the position. There is sometimes an idea that people who are independently wealthy are somehow less prone to corruption because that they “can’t be bought.” While surely there are individuals for whom this is true, Mellon used his position to vastly enrich himself.

Mellon followed similar policies to the last decade: pushing interest rates ultra low flooded the economy with low-quality debt. This drove up the price of existing assets - stocks, real estate and investments in commodities, instead of into “real economy” businesses.

After the crash, Mellon thought the answer was to let everyone go bankrupt - with the “free market” idea that once the prices of labour and everything else got low enough, the system would fire up again. He said:

“Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate. It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up from less competent people.”

In fact, it required a New Deal and government investment to lift people out of the Depression, because what Mellon and other classical liberals failed to consider was that those people who were all being liquidated - and even those that survived - were still carrying debt from when the economy was booming. The same thing happened in Japan in the 1990s.

It’s often claimed that the “Smoot-Hawley” tariffs were responsible for making the Depression worse, but this has been disputed - not least because until the 1930s, U.S. tariffs had been 30% for the previous century or so. The tariffs were only marginally increased.

The global financial crisis and the Euro crisis driven by Greece are perfect examples of economists’ failure to see a catastrophe coming.

They were often predicted by heterodox economists - so-called “Post-Keynesians” who follow Keynes legacy most faithfully, as well as proponents of MMT who recognized that the business cycle - the boom and bust - is driven by private debt.

To others - including Alan Greenspan - these crises somehow managed to be a complete surprise, followed by mass panic and policies that only manage to push the problem further down the road.

If you read reports of central banks the year before the global financial crisis, there is no clue that anything untoward might happen. Greece actually received a reward for one of the best run economies. Many governments had actually been in surplus.

In 2003, Robert Lucas, who is one of the architects of the neoclassical revolution of the 1970s, crowed in a lecture that the economics he had conceived had put an end to financial crises for good.

“My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.”

Lucas had displaced the inadequate models of 1970s Keynesian economics on the basis that they didn’t predict stagflation.

Romer points out our current hypocrisy, in that we overthrew Keynesian economics with a wholesale replacement that permeated every corner of the economy, with fundamentally conservative economic models that have prevailed no matter what party was in power, and they have led to crisis after crisis, including the one we are living in now.

“Using the worldwide loss of output as a metric, the financial crisis of 2008-9 shows that Lucas's prediction is far more serious failure than the prediction that the Keynesian models got wrong.”

Why isn’t it getting tossed out? Where is the accountability?

“In model after model the “identification” or cause is either assumed or imaginary.

In response to the observation that the shocks are imaginary, a standard defense invokes Milton Friedman's (1953) methodological assertion from unnamed authority that "the more significant the theory, the more unrealistic the assumptions (p.14)." More recently, "all models are false" seems to have become the universal hand-wave for dismissing any fact that does not conform to the model that is the current favorite.

The noncommittal relationship with the truth revealed by these methodological evasions and the "less than totally convinced.." dismissal of fact goes so far beyond post-modern irony that it deserves its own label. I suggest "post-real."

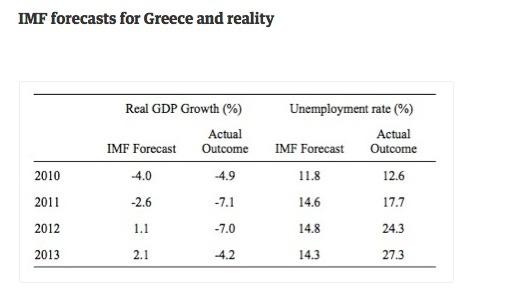

This also goes for disastrous interventions in the economy, when austerity is inevitably recommended. The Troika-imposed crushing of Greece’s economy shaved 30% off that country’s GDP - in defiance of projections that it would help. Year after year, the outcomes were consistently much worse.

The UK’s Telegraph reported that the IMF’s “top staff misled their own board, made a series of calamitous misjudgments in Greece, became euphoric cheerleaders for the Euro project, ignored warning signs of impending crisis, and collectively failed to grasp an elemental concept of currency theory.”

The result was 25% unemployment for adults and 50% unemployment for youth, while, as the New York Times reported that the hundreds of billions in bailout money for Greece never made it to the people. Between 60% and 95% of the bailout flowed straight back to its creditors - mostly banks in the UK, Germany and France, who had bought huge amounts of risky bonds from countries in the EU periphery - as well as Spanish mortgages and more.

What’s the conclusion here? Every single time there is a crisis, we are told that it’s because government broke the rules, because one core assumption of orthodox Neoclassical / Neoliberal economics is that the market, left to itself, will always return to balance.

This is truly a religious belief: the government has sinned against the perfection of the market, and now we must all pay the price, through economic fasting, self-flaggelation and hairshirts.

Virtually none of these economists - in government, business or academe - have the humility to recognize that the reason we’re in crisis is not because policymakers have been ignoring their advice, but because they have been following it.

Between 1940 and 1980, - the era of the “New Deal” and quasi-Keynesian policies, there were virtually no financial crises. Since 1980, there have been dozens, including some of the worst since 1929.

If you hired a bus driver from the Friedman-Lucas-Mises Institute of Bus Driving and one of their graduates drove a bus into a ditch, you might not fire them.

However, if all of the driver graduates were responsible for a series of catastrophic crashes, driving buses into rivers and lakes, over cliffs, over bridges, into flaming buildings, and every single time the driver said they didn’t see it coming, and the school said it was all the government’s fault, people would not be terribly sympathetic.

These are economic graduates who are responsible for crashing entire national economies, for bankrupting individuals and industries, for creating political and social unrest that leads to riots, famine, death. This is not an exaggeration. The business of government is not just law and order: it makes the difference between life and death, justice or injustice.

Keynes’ final paragraph of his General Theory is prophetic, because we have returned to the exact point we were at in trying to challenge classical liberal economics in the 1930s

This is why ideas matter. As John Maynard Keynes wrote, in words that should be graven on a new Rosetta stone in many languages:

. . . the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas. Not, indeed, immediately, but after a certain interval; for in the field of economic and political philosophy there are not many who are influenced by new theories after they are twenty-five or thirty years of age, so that the ideas which civil servants and politicians and even agitators apply to current events are not likely to be the newest. But, soon or late, it is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil.

The reason for this is that these are the ideas and assumptions that people base their decisions on.

And as Keynes points out, it is not just the established powers-that-be. “The ideas which civil servants and politicians and even agitators apply to current events are not likely to be the newest.”

This is also incredibly important from the point of view of reform, because for many “revolutionaries” and political zealots who are motivated by the belief that the whole struggle is one between good and evil, it is just a question of getting rid of the “problematic” people and it will be fixed by replacing them with “the right” people - while keeping the same broken structures in place.

Whether people are anarcho-libertarians, Ayn Rand fanatics, Austrian Mises devotees, or socialist, communists or left-wing libertarians, the ideas they are applying are “not the newest.” Beneath the rhetoric, the machine is the same - because the economics are the same. Communist Karl Marx and libertarian free trader David Ricardo have the same economics. Stalin’s Soviet Union and Mao’s China both ran “trickle down economics.” Social democratic parties across the west are all fiscal conservatives, and always have been. UK Labour has a history of austerity since its first election after the Second World War. The same is true of the CCF/NDP in Canada, which has the most fiscally conservative record of any party in government, with horrific social consequences that are ignored.

The Green Party is considered “left” for caring about the environment, but its economics are the same as Milton Friedman. They are “neoliberals on bikes,” and it is a political philosophy that is enshrined and enforced by law in many jurisdictions.

It effectively means that no matter who is elected, or where their propaganda is on their positions, the political spectrum isn’t a spectrum at all.

The Critics of MMT Aren’t Doing Their Homework

By contrast, proponents of Modern Monetary Theory have predicted many of the crises that neoclassical economists completely whiffed on, because they actually measure and include data in their model that orthodox economics does not.

What is even more egregious, however, are the superficial criticisms of MMT deployed to criticize it, which amount to not understanding it, because they can’t see how it fits in with their own view. That, however, is the point. It doesn’t “fit in” with their view, it replaces it with a different one.

If you’re lucky enough to have studied the history of science, and how intellectual revolutions in science take place, you may have heard about how scientists used to think combustion worked. In the 18th century, scientists would weigh an unburned material, then set it on fire, and weigh it again, and found that it was lighter. They thought that all combustible substances contained something called “phlogiston” which was released on burning. Scientists then realized this explanation did not make sense, and discovered that burning objects were actually reacting with what they called oxygen. Phlogiston was always imaginary.

The arguments presented against MMT treat it as a policy that sits on top of existing theories, when it replaces them.

During the pandemic, when the Federal Government’s fiscal efforts essentially kept the Canadian economy from complete collapse, two former Senior Finance Officials, Scott Clark and Peter DeVries, wrote in concern about the lack of apparent “fiscal guardrails,” and “fiscal anchors” during the single greatest public health emergency in a century, in which the national and global economy faced collapse due to an entirely new, highly contagious infectious disease that killed tens of thousands of Canadians and millions around the world.

Towards the end of their piece, they write “Nor can the government adopt the unproven strategy of simply borrowing “whatever is required” from the Bank of Canada “the Modern Monetary Theory.”

In that brief sentence, Clark and DeVries are making a number of errors about Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT.

First, having the Bank of Canada lend to the Government of Canada is not Modern Monetary Theory. What they are describing is a “monetized deficit” and it was used by the U.S. to fund 15% of the Second World War and was being used by the Bank of England to support the UK government during the pandemic in 2020.

MMT is not a theory about what we should be doing if we were to accept it. It is a theory that its proponents describe what is already actually happening, right now. Everything that governments and central banks and banks and business are doing right now can be explained through MMT. MMT is descriptive, not prescriptive.

Because MMT argues that money is created in a way that is different than our current economic framework does, it does offer different policy choices, with new opportunities, but also with new risks. Under MMT, there are still jobs not worth doing, investments not worth making, and wastes of time, effort and human endeavour and money.

If we are going to talk about a theory, or engage in discussion around competing ideas, we should at least do our best to have an informed debate.

In Canada, the Fraser Institute, the CD Howe institute and many others have written these critiques, all of which can be summed up as “well this disagrees with my theory of inflation” which is, in fact, the point.

As William K Black has pointed out, none of these critiques from high-profile supposedly “liberal” economists like Larry Summers or Paul Krugman mention the issue of predictive success and failure. “Nonsense theories produce nonsense predictions. One can be lucky predictively for several years, but not for a quarter-century. Krugman and Larry Summer’s instinctive approach to refuting MMT must have been to check out our predictive record. Why does no attack on MMT mention even a single predictive failure?”

An Investor Sums Up MMT

L Randall Wray, who has contributed to the development of MMT, shared what he called “the best response to the critics I’ve seen” - which is an article

WHY DOES EVERYONE HATE MMT? Groupthink In Economics, by James Montier, March 2019,

Not only does he take down prominent critics like Summers and Rogoff, he also provides a very useful 400 word summary of MMT. Some of you have asked for a concise statement, and this is as good as you’re likely to find.

Money is a creature of the state. Money is effectively an IOU. Anyone can issue money; the trouble is getting it accepted. The ability to impose taxes (or other obligations) makes a country’s ‘money’ valuable.

Understanding the monetary environment is vital. The monetary regime under which a country operates matters. Any country that issues debt only in its own currency and has a floating currency can be thought of as being monetarily sovereign. This means it cannot be forced to default on its debt (i.e. the U.S., Japan, and the UK, but not the Eurozone or most emerging markets).

An operational description of the monetary system is critical. Understanding that loans create deposits (which in turn create reserves, aka endogenous deposits create loans. For example, knowing that government deficit spending creates reserves and drives down interest rates is vital to understanding Japan’s bond market.

Functional finance, not sound finance. Fiscal policy is much more potent than monetary policy. Fiscal policy should be aimed at generating full employment while maintaining low inflation (rather than, say, achieving a balanced budget position). A Job Guarantee scheme is an example of a useful policy option to effect this outcome (acting like a buffer stock in a commodity market) in the eyes of MMT.

Limits are real resource and ecological limits. If any sector of the economy pushes it beyond the limits of capacity, then inflation will result. If a government spends too much or taxes too little, it can create inflation, but there is nothing unique about the government sector in this regard. These are the limits that matter – people, machines, factories – not ‘financing’ constraints.

Private debt matters. Even in a monetarily sovereign state, private debt matters. The private sector cannot print money to repay its debts. As such, it has the potential to create a systemic vulnerability. Think Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis: stability begets instability.

Macro accounting (Godley style) keeps us honest. One sector’s debt is another’s asset. So, the government’s debt is the private sector’s asset. Understanding how one sector relates to another using a sectoral balance framework is very helpful, as is understanding the Kalecki profits equation, or the way reserves work in a financial system. Accounting isn’t glamourous and identities shouldn’t be taken as behaviours, but they can help us spot unsustainable situations.

There you have it – my attempt to succinctly describe the core of MMT. Just under 400 words… hopefully short enough to satisfy even the most attention-challenged.

Now let’s have a quick look at some of the things that have been said by the great and the good and see how they map against this simple summary.

I’ll start with Ken Rogoff’s “Modern Monetary Nonsense”. This piece has very little to do with MMT at all as far as I can tell. His most serious point seems to be:

The U.S. is lucky that it can issue debt in dollars, but the printing press is not a panacea. If investors become more reluctant to hold a country’s debt, they probably will not be too thrilled about holding its currency, either. If that country tries to dump a lot of it on the market, inflation will result.

A similar sentiment is offered by Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, who said of MMT:

That’s garbage. I’m a big believer that deficits do matter. I’m a big believer that deficits are going to be driving interest rates much higher and could drive them to an unsustainable level.

Paul Krugman has adopted the same stance:

(Stephanie) Kelton seems to claim that expansionary fiscal policy…policy that pushes the IS curve out, will lead to lower, not higher interest rates. Why?

It seems as if she’s saying that deficits necessarily lead to an increase in the monetary base, that expansionary fiscal policy is automatically expansionary monetary policy. But that is so obviously untrue – think of the loose fiscal/tight money combination in the 1980s – that I hope she means something different. Yet I can’t figure out what that different thing might be.

An understanding of how the monetary and fiscal system actually works reveals this to be, to borrow Rogoff’s term, nonsense. In fact, when a government spends it simply tells the central bank to credit the government’s account with funds (created by keystrokes). Similarly, when a government taxes, these funds eventually end up as a credit to the government in its central bank account.

Ergo, when a government runs a fiscal deficit, it creates more money than it receives (by definition). This money is then used to purchase goods and services, so the central bank transfers money from the government’s account to the reserve account of the bank with which the sellers of goods and services happen to hold their accounts. This creates excess reserves at the bank. No bank willingly sits on excess reserves, and so money is lent out in the interbank market. This has the effect of lowering the interest rate towards zero (or to the level that the central bank pays on reserves).

Bonds are issued to 'mop up' these reserves and help the central bank hit its target.

Because the Fed pays interest on reserves, there is actually no need to issue bonds to help achieve its target at all these days (albeit this a new state of affairs given the Fed has only paid interest on reserves since 2008).

Larry Summers takes up the mantle here:

Contrary to the claims of modern monetary theorists, it is not true that governments can simply create new money to pay all liabilities coming due and avoid default. As the experience of any number of emerging markets demonstrates, past a certain point, this approach leads to hyperinflation.

Frankly, Summers makes some embarrassing errors in his analysis and one might reasonably conclude that he hasn't actually bothered to read anything that MMT economists have actually written. The first half of his statement is just flat out wrong for a monetarily sovereign nation such as the U.S. The second half tries to use nations that don't fit the criteria as a scare story for those that do. As noted above, most emerging market countries are not monetarily sovereign. They generally issue debt in multiple currencies and often have fixed exchange rate regimes, thus violating the conditions outlined above. These markets therefore offer no evidence of any relevance to the U.S. Hyperinflations, which I have addressed previously at length, are generally characterized by three traits:

1) large supply shock;

2) big debts in a foreign currency; and

3) distributive conflict.

The really odd thing is that Summers once knew all this.' Back in 2014 he noted,

We have a currency we print ourselves, and that fundamentally changes the nature of the macroeconomic dynamics in our country and all analogies between the United States and Greece are, in my judgment, deeply confused.

Sadly, the behaviour of the great and the good is far from exemplary in terms of economic debate. Terms like mess, foolish, fringe, nonsense, and voodoo alongside fear-mongering mentions of hyperinflations may make for an exciting story but they do little to advance the debate. In fact, the use of these words and the generally dismissive (but thoroughly unsubstantiated) nature of these articles appear to be typical of the output of those suffering from groupthink.

The term 'groupthink' was coined by Irving Janis in 1972. In his original work, Janis cited the Vietnam War and the Bay of Pigs invasion as prime examples of the groupthink mentality. However, modern examples are all too prevalent.

Groupthink is often characterised by:

A tendency to examine too few alternatives;

A lack of critical assessment of each other's ideas;

A high degree of selectivity in information gathering;

A lack of contingency planning;

Poor decisions are often rationalised;

The group has an illusion of invulnerability and shared morality;True feelings and beliefs are suppressed;

An illusion of unanimity is maintained;

Mind guards (essentially information sentinels) may be appointed to protect the group from negative information.

The failure in some cases to even bother to read - let alone understand - the elements of MMT coupled with name-calling suggests that the great and the good are acting more like mind guards (defending a broken orthodoxy) rather than academics evaluating an idea on its merits. A truly sad state of affairs.

I would add to this that there are other reasons for inflation - which are related to private market concentration and uncertainty.

The opposition to MMT is not about theory: it is about control, and who controls what. MMT recognizes that money is a creature, and monopoly of the state - not the private sector.

Above all, MMT is not a policy prescription. It is not saying “we should try doing it this way.”

MMT is a different, and arguably more accurate way of modelling the economy and financial system we have right now. It is “we should try seeing the economy this way, and when you do, you’ll see that we have different options.”

Those options include helicopter money - central banks directly printing cash and distributing it to the public. It includes monetized deficits, where the central bank prints money in lieu of borrowing the same amount. There is no reason to borrow to finance the government, deficit or not.

So, the idea that to cut taxes, you have to cut spending or run a deficit is false. What is happening now is that as the bubble bursts, everyone is running out of money and they know their bills are coming due, so they’re squeezing - and it’s all driving real desperation and violence.

MMT is not a panacea (nothing is). It does not make the impossible possible.

What it means is that we have much greater capacity to avoid crisis and achieve the achievable that the current economic system holds as a taboo, in defiance of reason, evidence, morality and common sense.

MMT includes corporations, and government, and innovation, banks, debt, money, the environment, as well as concerns about inflation, deficits and debts.

This is supremely important, because so much of the apocalyptic doomsday end-times fear of “collapse” is being driven by people’s lack of control in their own lives, which orthodox economists have amplified due to their belief that their own indicators must override what millions of angry people and voters are expressing.

The failure of these economics is pushing the world to crisis. It caused Brexit. It caused Trump and Trump 2.0, and it is feeding the forces seeking to snuff out democracy and the rule of law.

There is no question that with greater concentrations of private wealth, we see greater levels of outright corruption, which is extraordinarily damaging. It is corruption that can only be brought to bear and reduced by independent courts with the capacity to investigate and enforce the law.

It has to be said, this also what the radicals of the far left and the far right reject, and that liberal “centrists” have lost sight of.

There are two groups of people who oppose police and the law. There are people who are unfairly treated and oppressed when justice systems fail, because they are unjust. So on the left, you will see calls to “defund the police” which, as a slogan, manages to completely undermine the movement, since the actual request is to invest more in community supports to prevent crime.

The other group is criminals, fraudsters and cheats who don’t want to face the consequences of their actions when the police and courts are fair and do their jobs. This ranges from unethical and illegal practices on the part of certain corporations where they knowingly ignore the harm of their products, to the far more serious actions of organized crime.

The idea of dismantling government and replacing it with a small and efficient centrally run organization is the stated goal of both the far left and the far right. Lenin promised that under Communism, the state would “wither away,” which is also the expectation of right-wing libertarians. What they have in common - and why people will jump from left to right, skipping over the “moderate middle” is because social divisions are defined by refusing to accept authority.

The problem is that they are unwilling to accept any authority but their own, and that becomes reflected in radical governments whose policies (far right or far left) lead to collapse because they are rigid, inflexible and brittle.

The most important thing that can be said about MMT is that it means that many of the political and economic crises we face are a consequence of insisting that we follow the taboos of neoclassical economics, when these crises can be mitigated and avoided entirely using tools that are already available to central banks and governments.

Inequality is another word for concentration of more and more market power in the hands of fewer and fewer people. There are people out there who are genuinely suffering and oppressed who could benefit from having more control over their lives - especially financial control.

A final point. In the “real economy” people exchange money for something of value that is not money. That’s what makes it a win-win. In the financial economy, it is a zero-sum game, where the winner takes the losers’ money.

This is another aspect of our current crisis - and the economy. Because so much of the economy has been “financialized” it has become a zero-sum game.

Where there are no rules, there is no game. And this Zeit needs a new Geist.

As I have written elsewhere, the problem with the current economy is that we are in a superbubble, created by central banks, that poses an incredible threat when it bursts and the market reverts to the mean, which is $35-trillion in lost wealth in the U.S. alone.

Finally - this also means that the U.S., Canada, Europe and the UK do not need to privatize, or engage in austerity, which is what is pulling down all of our economies.

What is required is a Marshall Plan of structured debt reductions to prevent a crisis, paired with a New Deal of investments in re-industrialization. A Global Marshall Plan that made a concerted five years of investment in relief and renewal, we wouldn’t solve all of our problems. But we would solve a lot of them.

This would directly address what a lot of people are feeling: that we’re all losing our way of life. Nothing has to or should collapse. We have the capability to address it.

-30-

Dougald, whenever I read one of your posts it makes me want to find you and have a coffee and talk about what you have written. I came upon MMT because I was searching for a reason why the massive money supply expansion in 2008-09 did not result in massive inflation they way I had been taught that it would in grad school.

It has now been shown quite conclusively that there is no relationship between the money supply and inflation. And the “too much money chasing too few goods” monetarist explanation is incredibly simplistic in a way that Kelton and other MMT theorists make clear. Inflation that results from supply chain issues (such as experienced in the pandemic and its aftermath) needs a fiscal policy reponse aimed at increasing supply (or potentially regulating prices or even rationing in the short term).

Increasing central bank interest rates to address inflation (however caused) works. But the way it works is cruel and almost always “overshoots” its objective. Making business investment more expensive due to a higher rate of interest kills job growth which siphons wage income out of the economy, which leads to a lower rate of inflation.

So the wage earners typically in the bottom half (or third, or quarter) of the labour market pay an exorbitant cost of the “war on inflation” while those holding assets benefit. I am not a communist but this doesn’t sound like a plan any democratic country should be pursuing on behalf of its citizens.

Dougald you have mentioned the New Deal and the changes ushered in by FDR in several posts. One of the very significant changes that occurred during WWII and was cemented through unions after the war was the 40 hour work week.

Prior to WWII the typical full time work week was 60 hours! Rifkin in The End of Work makes a convincing case that the Depression was largely caused by wage income not keeping pace in the economy with productivity gains as the US industrialized its economy. Workers simply could not afford to buy what the economy was producing and the economy ground to a halt.

Not only did the work week decline to 40 hours post-war, but incomes also rose! In effect the balance between worker productivity and earnings was “reset” and remained in step as the economy grew until about 1978/9. Policy decisions by government systematically empowered corporations in the wage setting process and in fact, inflation assists this process in that wages did not rise as fast as prices throughout the next 4 decades.

Anyway, this is turning into its own post (sorry).

PS. Love the works of Keynes and J. Kenneth Galbraith.