In 1929, Canada had an election where bigots made education and children's identities the main issue. The bigots won - with the help of the KKK. (Part 2)

A Conservative MP wrote to Prime Minister R B Bennett: the Klan was 'the most complete political organization ever known' in Western Canada. But it wasn't just Conservatives.

Given world events in 1929 – it is not surprising that few people have heard of a provincial election in Canada where the Ku Klux Klan helped topple a government.

It is better known as the year where the stock market meltdown triggered a global Depression leading to the greatest world conflict yet in history, World War II.

But in 1929, the Liberal Government in Saskatchewan was defeated, and Conservatives elected, because of the Saskatchewan KKK. The KKK’s leaders were present at the Conservative convention when members chose their new leader, Dr. J. M. Anderson.

“The Conservative party provincial convention was held in Saskatoon on March 15 and 16, 1928. A total of three hundred and four delegates were present, averaging five for each of the sixty-three constituencies in the province. At this convention the Conservatives and the Ku Klux Klan had managed to find each other. Dr. Rosborough, the Imperial Wizard, Mr. Ellis of Regina, the Klan Kligrapp (secretary) and Dr. Hawkins were all present at the convention. Dr. Hawkins was an observer, the other two were delegates, and Klan literature was available at the door and inside the convention hall.

The convention elected the M.L.A. for Saskatoon, Dr. J.M. Anderson, leader of the provincial party.”

The Conservatives and the Klan were not the only two parties who were teaming up. As Calderwood writes,

“Progressive-Conservative collaboration began officially at the time of the Conservative Convention at Saskatoon in March, 1928.

Before the Convention closed, it received the following cable from Dr. Tran, the Progressive leader in the legislature:

“Heartily concur in the spirit of your deliberation. Gladly accept any democratic principle re co-operation.”

Behind this cable lay secret negotiations conducted on March 4th between Dr. Anderson, J. F. Bryant, and Howard McConnell and Progressive members of the Saskatchewan Legislature and the Provincial Progressive Committee.

The negotiations were planned “with a view to arriving at some compromise” by which they could conduct the next election.

The following compromise was reached at the meeting: the Conservatives would run a Conservative candidate in certain constituencies (about fifty per cent) and have the Progressives run a candidate in each of the other constituencies where the Progressives were the strongest.

If in any constituency neither the Progressives nor Conservatives would accept any suggestions from the Central Committee, then an open convention would be called of all opposing the Government and the strongest man get the nomination.

A resolution embodying this compromise was to be brought before the Conservative Convention.

If the motion passed, then Progressive members of the Legislature were to be contacted by telegram to determine whether they would support a co-operative government if the Liberals were defeated, replies were to be read to the Convention. The Liberals were shocked that the “liberal” Progressives would even think of an alliance with the “reactionary” Conservatives.”

Calderwood goes on to suggest that the Progressives were more willing to work with “co-operative” Conservatives in government than un-cooperative Liberals – but never mentions eugenics at all.

Anthony Appleblatt writes that under the two leaders of the Saskatchewan KKK, Hawkins and Maloney,

“the Klan became violently anti-Catholic and stirred up old prejudices and hatreds… During 1928 three issues came to the fore: crucifixes on public school walls, nuns teaching in public schools, and the teaching of French in public schools. The Liberal party led by James Gardiner continued their traditional policy of defending separate school privileges and maintaining the minimum amount of French permitted by the law.”

Daniel C Grant had returned to Saskatchewan from Manitoba to campaign in 1929 to work “off and on as a bodyguard and advance man for J.J Maloney,” who headed up the Saskatchewan KKK.

Maloney was printing a KKK newspaper, the Western Freedman, with headlines accusing the Roman Catholics of forcing protestant children to kiss crucifixes as a form of punishment. Another headline accused the minority Roman Catholic population of 19% of running the government.

It’s worth considering this context - when addressing the accusations of corruption made by KKK and the Conservatives towards the Liberals – that their sense of what was “corrupt” was based partly on their own values of religious and ethnic bigotry and prohibition of alcohol. Many were, in the words of the Mother Superior above, “fanatics.”

They thought Liberals were corrupt by association – that the Liberals dealt with people who were corrupt themselves, at least by the lights of the KKK, Conservatives and pro-Eugenics Progressives and CCFers-to-be. If you weren’t British, it made you illegitimate and “less than” in their eyes – and therefore, illegitimate voters and an illegitimate government. After all, the Liberals tolerated alcohol, Jews, allowed separate French Catholic schools and immigration, as well as Catholic immigrants from Poland and Ukraine.

Conservatives, Progressives and the KKK wanted British Protestantism to be the default, and they promised to curtail French education in Saskatchewan, and immigrants would be accused of taking people’s jobs.

John Diefenbaker was a Conservative candidate for MLA in Prince Albert in the 1929 election and was accused of being a member of the Klan. Diefenbaker refused to answer directly. However, his campaign made it clear where he stood:

“The day before the election, the Conservatives ran an ad in a Prince Albert newspaper, declaring “A vote for a Gardiner candidate will ensure a continuation of indiscriminate dumping of immigrants into Saskatchewan with resulting workless days and lower wages for you.”

Prohibition & The Law

Another “shared interest” leading to accusations of corruption was alcohol and prohibition. Because of the truly shocking levels of drinking that were happening before prohibition, the issue of prohibition created common ground with “progressives” including women’s rights advocates, the Ku Klux Klan, and many Protestant churches who were concerned about drunkenness, prostitution, pregnancy, disease and violence against women.

When it came to who was being blamed, there was an element of bigotry:

“The fight to keep Canada dry was related to the fight to keep Canada British since foreigners and Catholics were portrayed as the primary culprits of the liquor traffic. It was noted that Jews, such as the Bronfmans, were prominent bootleggers, and press reports of drunkenness, and the mayhem that went with it, regularly featured persons with foreign-sounding names. St. Peter’s Messenger, a Catholic newspaper, reported: “The leaders of the prohibition league are ... filled with a virulent hatred of the Roman Catholic church and all that belongs to it.”

Pitsula writes:

“Part of the Klan’s organizing techniques was to approach Protestant ministers and enlist their support, which many were happy to give since the Klan’s concerns about crime and vice mirrored their own…

William Calderwood identified twenty-six Protestant ministers in Saskatchewan who belonged to the Klan or who were directly involved in it. They included 13 United Church ministers, 4 Baptist, 4, Anglican, 3 presbyterian, 1 Lutheran and 1 Pentecostal. They were attracted to the Klan not only became it was anti-Catholic but because of its stand on moral reform … reverend W. Titley of Imperial, maintained that the Klan existed to defend Protestant rights and truths, and he urged “every true Protestant to support it.” Baptist Ministers T.J. Hind and William Surman, both active in the Klan, were elected, respectively president and secretary of the Baptist Convention in Saskatchewan. In 1930, three members of the Klan were appointed to the Social Services Committee of the Assiniboia Presbytery of the United Church.”

He continues:

“In the United States it is estimated that as many as 40,000 fundamentalist ministers joined the Klan… Many clergymen drawn to the Klan in Saskatchewan were frustrated by the Gardiner’ government’s failure to properly enforce the prohibition laws. This was a charge echoed by the Anderson Conservatives, which forged yet another link between moral crusaders and the anti-Liberal forces in the province.”

Here there may be some confusion, when it’s suggested that clergy were being driven to the Klan because the Gardiner government didn’t enforce prohibition. That is because prohibition had already ended in Saskatchewan five years earlier, in July 1924. Gardiner wasn’t even Premier at the time.

During that time, making and selling alcohol in Saskatchewan was legal. It was even legal to export that alcohol to the U.S. Harry Bronfman’s US customers were living under prohibition – not him. It could certainly be that people were scandalized by investigations into the Bronfman’s behaviour in trying to get around U.S. prohibition laws to sell their alcohol, but prohibition in Saskatchewan had been over for five years.

Pitsula also uses the passive description “drawn to the Klan” as if clergy were moths and the Klan were a light bulb. He is looking for acceptable, reasonable explanation that will help justify why protestant clergy would support the Klan.

The explanation for their joining was not based on reason and could not be justified by the facts – that they might be drawn to the Klan, not by high-minded reasons of morality, and concern, but for uglier reasons of hate and religious bigotry, which the Klan was exploiting.

Finally, there were accusations of patronage-type scandals. Of all the accusations of corruption, these were the most justified. The Liberals had been in power a long time, and one of the issues was patronage at the Weyburn Mental Hospital. The person in charge was a Liberal without health care experience, and there were tragic stories of patients not being properly cared for.

But the major issue of the election wasn’t health care, or corruption – it was the Conservatives, Progressives and KKK’s whipping up hatred against a Catholic minority, and the primes to take away their rights to teach their children in separate schools, at all. This is euphemized as a “schools question.”

Jimmy Gardiner Vs the Ku Klux Klan

James Gray names a chapter of his book The Roar of the 20s, “Jimmy Gardiner Vs the Ku Klux Klan” Gardiner was the Premier of Saskatchewan (and later became a member of parliament). His dislike of the Klan was not just political posturing. He came by it honestly. He ran a harsh anti-Klan campaign, in government as well as during the campaign. Some thought that he was going too hard on the KKK, and that it cost the party support.

Though Gardiner supported Catholics and immigration, he, personally was Presbyterian. He was one of the founders of the United Church of Canada. Though Gardiner was accused of being lax on liquor, he personally was a teetotaler.

“Gardiner was both a Liberal and a liberal, by the standards of the day. Born into a hardscrabble family in rural southwestern Ontario, the future premier worked his way up and across the country from farm hand to teacher’s college to an elected member of the Saskatchewan Legislative Assembly in 1912.

His teaching experience at a series of rural schools in Saskatchewan brought him into close contact with immigrants — Jews, Ukrainians, Poles, Germans, English. His most formative experience was as principal of the school at Lemberg, just east of Regina near Qu’Appelle. The community in turn supported him by sending him to the legislature as their local MLA.”

Gardiner was also a pioneer of free health care in a province where Tommy Douglas gets all the credit. As premier of Saskatchewan in 1928, Gardiner championed the Saskatchewan Sanitoria and Hospitals Act, the first legislation to provide free hospitalization and treatment for victims of tuberculosis anywhere in North America. It was passed unanimously by the provincial legislature on January 1, 1929.

Gardiner was relentless in the pursuit of the Klan, but during the campaign, Pitsula reports that Coldwell was supposedly “far from convinced” at the involvement of the Conservatives and the Klan at the time.

It is hard to know whether Coldwell’s claim is sincere or “plausible deniability” for the sake of political reputation, but Pitsula might have been more skeptical, given Calderwell’s evidence of Progressive involvement with the KKK.

When the results were in, the Liberals won the most votes and the most seats, but not enough for a majority. The seat count was:

Liberals – 28

Conservative – 24

Independent – 6

Progressive – 6

Gardiner tried to run a minority government, his opponents voted against him, and he resigned his seat. The Regina paper called Gardiner a “usurper” – all for trying to form government with the most support!

The Conservatives took power instead, supported by the Progressives and independents, who all formed government together, with the Liberals in opposition. The condition of the Progressives supporting the Conservatives was that they call an inquiry into alleged Liberal patronage at the Weyburn Mental Hospital.

When it was built and opened in 1921, the Weyburn Mental Hospital was the single largest building ever built to date in the British Empire.

It’s worth saying, briefly that despite Weyburn being a “small town” the Weyburn Mental Hospital was not just the local hospital with a ward for mental patients. When it was built and opened in 1921, the Weyburn Mental Hospital was the single largest building ever built to date in the British Empire.

Not just the largest building in Saskatchewan, or Canada, or North America. The largest building in the British Empire.

“The Progressive Party, with which Coldwell was then allied, threw its support to the Conservatives, which along with that of the independents enabled Anderson to take over the government.

The price of Progressive support was a commitment by Anderson that a royal commission would be established to investigate the relationship of the civil servants with the Liberal Party machine. Anderson also gave his assurance that none of the government’s employees would be fired while the inquiry was proceeding. Coldwell was appointed chairman of the commission.”

To repeat: the price of Progressive support was for the Conservatives to call an inquiry into the Liberals, and M. J. Coldwell was appointed chairman.

Coldwell maintained he had seen no concrete proof of connections between Conservatives and the Klan until after the election. That is despite his having witnessed events like this:

“Coldwell himself recalled being introduced to [Dr. John H.] Hawkins at the Kitchener Hotel during the 1929 election campaign. He was leaving a radio studio in the hotel when [Conservative Leader J. T. M.] Anderson and Hawkins were coming in, and after the introduction they chatted about the campaign for a while. It was only later that Coldwell learned that Hawkins was the Imperial Wizard of the Klan.”

According to Pitsula, hard proof of Conservative - Klan collusion was only confirmed later, in the form of a membership list that came to light as a side-effect of Coldwell’s inquiry.

“Two employees were fired and the wife of one appealed to Coldwell to get her husband's job back. He had, she said, joined the Ku Klux Klan on instructions from the government to provide it with inside information. She gave Coldwell a complete membership list of the Regina organization.

“I was astounded at the number of highly placed Conservatives who were on that list,” Coldwell said, adding that he had destroyed the list when he left Regina for Ottawa twenty years later.”

Consider, for a moment, that in popular Canadian political mythology, that “progressives” who established the CCF and the NDP are supposed to be opposed to conservatives more than anyone.

You would think that such a list in the hands of a political opponent would be more than political dynamite – it would be a political volcanic eruption.

You would think that if Coldwell and the Progressives or the other parties he was aligned with opposed the KKK, or wanted to expose the Conservatives, they had an opportunity – maybe even an obligation – to make the names of members known. Coldwell would certainly have found out the people in all parties who were on that list – not just Conservative. He didn’t make it a campaign issue.

In Martin Robin's Shades of Right: Nativist and Fascist Politics in Canada 1920-1940 he cites a truly chilling passage:

“Klan membership lists were filled with the names of Tory supporters, and their meetings attended and harangued by party activists. According to Dr Walter D. Cowan, the Klan treasurer, Regina Conservative elected for Long Lake to the House of Commons in the general election of 1930, and columnist for the Regina Standard, the Klan was 'the most complete political organization ever known' in the West. 'Every organizer in it is a Tory,' he wrote R.B. Bennett. 'It cost over a thousand dollars a week to pay them. I know it for I pay them. And I never pay a Grit. Smile when you hear anything about this organization and keep silent.”

Coldwell was put in charge of an investigation into corruption at the Weyburn Mental Hospital, which made national headlines - though Coldwell, as a sitting Alderman with political ambitions, may not have been the most impartial judge.

The local MLA for Weyburn, Robert Sterritt Leslie, was a Progressive. He was Minister of Knox Presbyterian Church in Weyburn and spent most of his time as MLA as Speaker of the House. He also publicly “expressed his hope that eugenic sterilization would soon be part of a solution to the problem of a constantly growing hospital population.”

Again, the rail and the KKK played a role – there had been an influx of Americans on the rail lines and the area around Weyburn had one of the strongest concentrations of KKK associations.

This was the political environment in Saskatchewan that a young Tommy Douglas found himself moving into in 1930 from Brandon, Manitoba. Douglas was moving to Weyburn, and in 1935, Dan Grant helped Douglas win his first election as Member of Parliament.

Daniel Carlyle Grant and the 1935 Douglas campaign

It is very clear that even historians struggle with the idea that the CCF’s values were incompatible with eugenics, based on the party’s well-crafted, post-success brand as champions of the underdog. The fact that Douglas was elected in 1935 with the help of one of the Ku Klux Klan’s Organizers creates cognitive dissonance so intense it could be measured with the Richter scale.

In his book, The Ku Klux Klan in Canada, Allan Bartley, writes

“Daniel Carlyle Grant, the Klan worker rewarded by the Conservative Saskatchewan government in 1929 with a job in Weyburn, did not fare well as the Depression hit its depth. The new Liberal government fired him in 1934. Grant wanted revenge, and he sought it by working for Tommy Douglas, the firebrand candidate representing the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), a political formation that found Klan ideals abhorrent.”

Bartley is assuming – and he is offering - a rationale that creates a both a defense for the CCF and sympathy and supposed understanding for Grant.

It’s true, that there is no reason to believe that Douglas was aware of speeches like this one, given by Grant on October 16, 1928, at the Norman Dance Hall on Sherbrook in Winnipeg, where, he told an audience of 150 that:

“The Klan strove for “racial purity. We fight against intermarrying of Negroes and whites, Japs and White, Chinese and Whites. This intermarriage is a menace to the world. If I am walking down the street and a Negro doesn’t give me half the sidewalk, I know what to do.” He then lashed out at the Jews and said that “The Jews are too powerful ... they are the slave masters who are throttling the throats of white persons to enrich themselves.” Grant claimed that the federal Liberal government was allowing the “scum of Papist Europe to flood the country and refuse to allow immigrants into the country who are not Roman Catholic ...”

Clearly, not everyone in the CCF found Klan ideals “abhorrent” – they shared many of them – eugenics, sterilization, prohibition, and a protestant opposition to, and even hatred of, Catholicism.

And surely, if the KKK was so problematic, a principled and idealistic man like Tommy Douglas would never take Daniel Carlyle Grant, KKK organizer, to be a key figure in his 1935 campaign for CCF Member of Parliament.

One of the defining features of propaganda as history – and why we believe it - is that for many it can be more palatable to believe ludicrous but reassuring lies than to face up to harsh truths.

Many of the reports of Daniel C. Grant’s decision to work for Douglas have a twinge of sympathy about them. When Bartley describes Daniel Carlyle Grant as not faring well and saying that he “wanted revenge” treats Grant as the victim who is in the right.

Revenge? For being fired by a Saskatchewan Liberal government that didn’t want KKK organizers working in the employment bureau? Grant was in charge of jobs in the Depression in Saskatchewan, a job he obtained by being an KKK organizer. What are his hiring practices going to look like?

This framing appears to be that this poor fellow found himself unemployed in the middle of the Depression in Saskatchewan, after the Liberals were re-elected. Unlike many, he had actually had a government job for the first four years of the Depression. And Grant was fired for the same reason he was hired in the first place: he was a KKK organizer who spent years making money selling the vilest kind of hate.

Who, in painting Carlyle as a victim, is on the right side of history?

The Liberals are the ones who thought that KKK organizer and hatemonger didn’t belong in politics or working for government. Tommy Douglas is the one who disagreed.

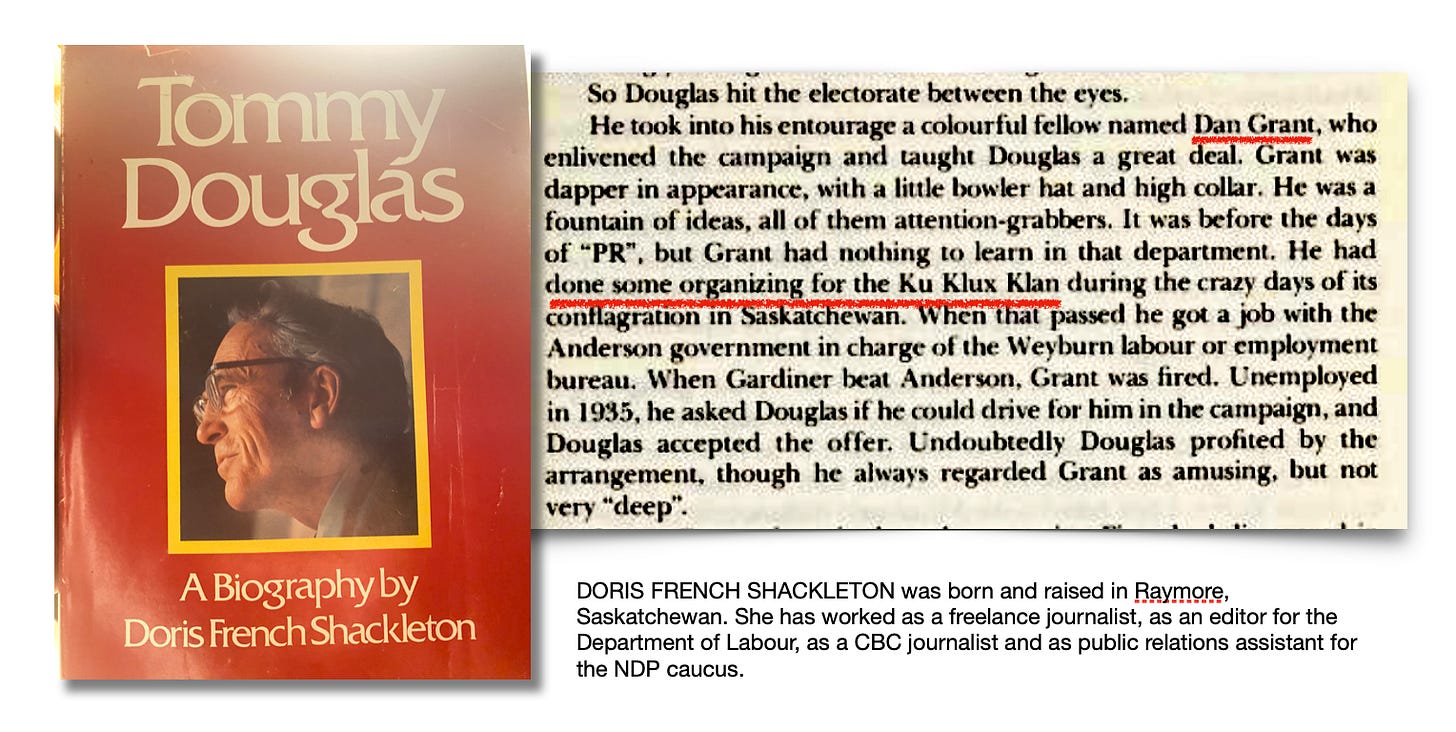

The fact that Grant was a KKK organizer is freely conceded in a 1974 biography of Douglas Tommy Douglas, by Doris Shackleton. Shackleton was “was active in the CCF youth movement in the province and she worked as a teacher before moving in 1945 to Ottawa. There, she worked as a freelance journalist, then as an editor for the Department of Labour, as a journalist for the CBC, and, in 1971, as public relations assistant to the NDP caucus.”

“[Tommy Douglas] took into his entourage a colourful fellow named Dan Grant, who enlivened the campaign and taught Douglas a great deal. Grant was dapper in appearance, with a little bowler hat and high collar, He was a fountain of ideas, all of them attention-grabbers. It was before the days of “PR”, but Grant had nothing to learn in that department. He had done some organizing for the Ku Klux Klan during the crazy days of its conflagration in Saskatchewan. When that passed he got a job with the Anderson government in charge of the Weyburn labour or employment bureau. When Gardiner beat Anderson, Grant was fired. Unemployed in 1935, he asked Douglas if he could drive for him in the campaign, and Douglas accepted the offer. Undoubtedly Douglas profited by the arrangement, though he always regarded Grant as amusing, but not very “deep”.

Margoshes book clearly draws from Shackleton, and says much the same thing.

By contrast, in “The Making of a Socialist” Douglas speaks at length about the campaign, about Grant and his impact, but never mentions the link to the KKK, even when pressed about Grant’s background. The book is a series of transcribed interviews conducted in 1958 with political journalist Chris Higginbotham.

“[Higginbotham] “Where did your friend Mr. Grant come from?

[Douglas:] He had been in Weyburn. Prior to becoming unemployed he was in charge of the Labour Bureau for the Anderson administration.

The provincial government kept a labour office, then after the Liberals came in, in 1934, he was dismissed and without a job.

Did you know anything about his background?

Very little. When he had been in the provincial labour office in Weyburn, I used to have quite healthy battles with him over relief schedules and things of that sort. But it wasn't until the election that I got to know him quite well, and grew to be very fond of him.”

For many reasons, it is difficult to believe that Douglas was unaware of the KKK association - especially given the fact that it was openly disclosed in another Douglas biography, which was first published in 1975, when Douglas was still alive.

Grant helped Douglas in every way: he was a fundraiser for his campaign, taking donations through a lottery for a campaign car that could be used during the campaign, then awarded at the end. He gave Douglas communications advice - taught him how to focus on “wedge issues,” created pamphlets and taught Douglas not to use “academic” speeches but to tell funny stories.

This technique was drawn right from the Klan campaign playbook. As historian James Pitsula wrote:

“The Klan offered a populist type of British Protestant nationalism, such as the Orange Lodge did not provide. The Klan went out to the people. It held public meetings and sent out charismatic lecturers, almost in the style of evangelical preachers. It created drama and excitement with a hint of romance and danger. Crosses burned on dark hillsides, fiery spectacles visible for kilometres around. There was something darkly primitive about the Klan, and yet it also had a comic side. Klan lecturers told funny stories and used humour as a weapon. A Klan rally was entertaining, vulgar but not boring.”

As Shackleton described it, Douglas had “discovered political shorthand,” but the way in which the story is presented is doubly dishonest and deceptive. She writes:

“You cannot explain at length to thousands of people. You cannot tell them in detail how the Liberals, as he believed, were restricting the economy instead of expanding it to meet the challenge of the depression. One significant statement had to say it all.

He would be accused of being simplistic. He mastered the art of finding the one exciting circumstance that immediately transfers a whole body of fact.

He learned in 1935 that drama belongs in politics, that it is a political crime to be dull. He had been a fervent and compelling preacher, and he had been a skilled entertainer. He put the two parts together.

“I began telling jokes,” Douglas said, “because those people needed entertainment. They looked so tired and frustrated and weary. The women particularly. They had all the back-breaking work to do. So I used to tell the jokes to cheer them up.”

“And when they're laughing they're listening.”

The first misleading statement is subtle, because saying that Douglas “had discovered political shorthand” shifts responsibility for learning these campaign techniques away from Grant, and makes it seem as if Douglas developed them himself. Grant, after all, had seen and used campaign techniques of the Klan up close and first hand – both as a recruiter himself and as a bodyguard and organizer for the KKK’s leader J. J. Maloney.

The other misleading statement is a significant error in fact and history: when Shackleton says, “the Liberals, as he believed, were restricting the economy instead of expanding it to meet the challenge of the Depression,” is untrue for the simple reason that the Liberals were not in power or running the government.

In the 1935 election, the incumbent government of Canada was Conservative, not Liberal. The Prime Minister was R. B. Bennett. The Liberals, led by Mackenzie King, were the opposition, seeking to defeat the Conservatives, which they did.

When you consider who Douglas and Shackelton reflexively see as allies and opponents in the 1935 campaign, it is revealing. The party that had been running Canada for the first years of the Depression were the Conservatives. But Shackleton has Douglas blaming the Liberals. Douglas and his campaign aren’t modern-day progressives aligning with Liberals against conservatives – they are anti-Liberal, and aligning themselves with everyone else who was, too.

For Douglas and the CCF, this is a regular pattern. In the 1938 provincial election in Saskatchewan, the opposition parties were despairing at the possibility of another Liberal victory. Douglas, in The Making of a Socialist, says:

The “provincial election in 1938 … That was a terrible schemozzle from our standpoint. George Williams got the idea that the government would be almost impossible to defeat, and that to prevent the C.C.F. from being annihilated, he should enter into an arrangement with the Conservatives and the Social Crediters to saw off seats. The result was that we only ran thirty-one candidates.”

This is an interesting comment from Douglas, because the strategy is exactly the deal that the Progressives (and Douglas’ mentor M. J. Coldwell) had used effectively to get into a Coalition with the Conservatives in 1929. However, it’s also clear that Douglas has an axe to grind – because Williams tried to get Douglas removed as a candidate in the election he had won in 1935.

That’s because not only did Douglas have a KKK organizer as a driver, fundraiser, advisor, and organizer in Grant, Grant successfully secured an endorsement from Bill Aberhart, the recently elected far-right Social Credit Premier of Alberta.

The endorsement from a Premier of a party some saw as fascist nearly got Douglas fired as a candidate, but may have also won him the election.

Social Credit was seen as a hard core ultra-right party. Aberhart was a radio preacher and evangelical who had worked with the United Farmers of Alberta before coming across some Social Credit theories of guaranteed income. There were a couple of problems with the whole scheme. One was that social credit as a movement was undermined by the antisemitic conspiracy theories of its proponent, Major Douglas. Another was that for the scheme to work, it would have to be legal for the province of Alberta to print its own money, which it is not. That did not stop Aberhart from trying.

“Political sleight of hand worthy of Watergate”

There are different accounts of just how Social Credit was involved in Douglas’ campaign, but Bible Bill Aberhart was dragged into Tommy Douglas’ 1935 campaign for MP in Saskatchewan, because there had been a rumour that the Liberals were going to pay a phony Social Credit candidate to run to split the vote. Grant took the news to Aberhart, who was appearing in Regina. Aberhart agreed that if the candidate was fake, he would denounce them and endorse Douglas instead.

Aberhart’s endorsement caused a split in the CCF party, with farmers and labour calling for the CCF to cut ties with any candidate who was endorsed by Social Credit. One CCF candidate, Jacob Benson of Yorkton, “lost his farmer-labour credentials.”

Tommy Douglas was spared by M.J. Coldwell, who was now the CCF Party President in Saskatchewan, and was also running as a candidate for MP. Here is Douglas telling the story himself in The Making of a Socialist.

“[Daniel C Grant] said, “I'm going to talk to Aberhart.” So off he went. He told Aberhart that if the Social Credit wanted to run a candidate against me, that was their business and their privilege, but that he did object to the Social Credit party allowing its name to be used by the Liberal dummy candidate.

Aberhart got quite indignant, said he certainly wouldn't stand for this, and asked, “Would Douglas run as Social Credit?” Grant said, “Certainly not.” Then he said,

“Are there any Social Crediters there at all?” Grant said. “There may be some, I think we could find them.”

“Well,” said Aberhart, “would the Social Credit people there endorse this candidate? Because if they will, I will denounce this Liberal stooge as a fake.”

So Grant came back to the Weyburn constituency and rounded up twenty or thirty people who proceeded to hold a Social Credit convention, at which they said there wasn't any Social Credit candidate running, and that they had written authority from Mr. Aberhart to say that the alleged Social Credit candidate wasn't Social Credit at all, but was being financed by the Liberal party. They called on any Social Crediters in the constituency to support me. This was published and played up by the press that I was running as the C.C.F. Social Credit candidate.

But at no time was I ever in any way associated with the Social Credit party, except that I did accept their endorsement and their C.C.F politician support, although there weren't actually many Social Crediters in the constituency.”

None of this denial makes any sense. His campaign went out of their way to secure a Premier’s endorsement, including staging a fake meeting pretending to be another political party. All that even though there weren’t many Social Crediters?

Shackleton’s book Tommy Douglas tells a slightly different story.

She makes it quite clear that the Social Credit meeting to denounce the phony candidate was a sham – the “Social Credit convention” was “packed, it was said, with CCFers” who repudiated the Social Credit candidate and endorsed Douglas instead. In today’s terms, this would be “astroturfing” – completely hijacking an organization to create the false impression of grassroots support.

What’s more, while Douglas says in 1958 that he did accept the Social Credit endorsement, Shackleton says he didn’t – and that is what saved him from being removed as a candidate.

“Douglas never acknowledged the endorsation, and this saved his skin when George Williams got the provincial Farmer-Labour executive to agree to disown any candidates who had entered into an alliance with the monetary reformers from the next province. One CF candidate, Jacob Benson, nominated in Yorkton, lost his Farmer-Labour credentials for this reason. Williams, hearing of the Weyburn situation, wanted M. J. Coldwell as provincial president to issue a statement also repudiating Douglas. Coldwell refused to do so.”

Douglas won by less than 300 votes and went to Ottawa. Later, as he mentioned, he blamed George Williams for the 1938 election loss– the CCFer who wanted Douglas fired as a candidate for taking a Social Credit endorsement. The Social Credit connection had deeper roots.

From “The Making of a Socialist”

The way I heard, while the meeting was called a Social Credit nominating meeting, there weren't any Social Crediters there and they nominated you as their candidate.

No, they didn't nominate me, they simply endorsed my nomination. Their resolution said that since they were not running a candidate, they would endorse my nomination and call on the people of the constituency to support me.

From that time on there was quite a lot of perturbation among the C.C.F. hierarchy, because at least one newspaper reported that you were in serious trouble from your ties with the Social Credit party. I presume they didn't know the story at all.

That's right, they didn't know the story. In those days we had no central organization. Every candidate ran on his own. We had little or no money for organizers or expense money to call candidates in to candidate schools. So, it was a matter of every man for himself, and Mr. George Williams, who at that time was leader of the opposition in the Saskatchewan Legislature, became very much perturbed about these reports that I was running as a C.C.F.-Social Credit candidate, and at one time he wanted the executive to expel me.

Mr. Coldwell, who was still provincial president and provincial leader of the C.C.F., would have no part of it until he heard my side of the story. When the election was over, and I laid all the facts before them, the copies of the resolution, and the other data, the whole matter was dropped.

That's haunted you, though, hasn't it?

Oh, yes.

I suppose that many people in Saskatchewan never really got the true story.

I'm sure most of them didn't know it.”

Of all the things that Douglas said, the idea that he’s sure that “many people in Saskatchewan never really got the true story” brims with irony.

In fact, there’s a third account, in Building the New Society:

“What followed was a piece of political sleight of hand worthy of Watergate, not illegal but far from proper. It got Tommy into a world of trouble - but also may have been the final trick that got him elected.

The way Tommy, campaign manager Ted Stinson, and Dan Grant saw it, even if a real Social Credit candidate didn't emerge, the Liberals might put up a phony one. Either way, the CCF would lose votes.

In early September, Stinson met with an Aberhart lieutenant in Moose Jaw and won an agreement that the new Alberta premier would endorse Tommy if he could win local Social Credit support…

Tommy's first move was to issue a statement, echoing the one from Coldwell and Williams but going a bit further: if he was elected, he told The Weyburn Review, he was "prepared to initiate and support legislation... which would make possible the Social Credit system being operated in any province caring to do so."

As mentioned above, all of this got Douglas in trouble.

… Williams and the others wanted him out, but the doctor persuaded them to hear first from Coldwell, who hadn't been able to make it to the meeting. The next day, Coldwell threatened to resign if Tommy was disciplined. Ejecting the Weyburn candidate "would have regrettable repercussions for the whole movement," he argued.”

The links between Douglas and Social Credit did not end with Douglas getting elected MP in 1935. Shackleton notes that Douglas’ saw Social Credit as potential allies, even when some considered it to be fascist.

“The confusion over Social Credit as a kindred or a hostile doctrine lingered for a few years - probably until John Blackmore began antisemitic barrages in the name of Social Credit. In the beginning, several Alberta CCF members including William Irvine had been instrumental in bringing Major Douglas, head of Social Credit in England, to speak in Canada. Monetary reform was a strong mutual concern. But Woodsworth denounced Social Credit as one more capitalist party and Coldwell, at least at a later date, saw fascist elements in it. Douglas took a softer approach.

In a letter to Coldwell in 1936 he said:

‘I cannot altogether agree with your expressed strategy in dealing with the Social Credit forces. My experience throughout this province is that while there is a general admission that Aberhart is bound to fail, there is a feeling on the part of those who supported him that they want some place to go. The last place they are likely to go is to the people who have held them up to ridicule .. when those who have supported Social Credit come to realize its inherent weakness they will find a more comfortable home in the ranks of the CCF.’”

Douglas’ prediction of the collapse of the Social Credit Party took a lot longer than he might have expected. The Social Credit Party in Alberta stayed in power for 36 consecutive years, until 1971, one of the longest unbroken runs in government at the provincial level in Canada. It was replaced by Progressive Conservatives.

some of the most significant political figures in the history of both the NDP and the Progressive Conservatives, two of Canada’s major political parties, have an embarrassing history they would rather not discuss. That includes national leaders of both parties. The founding leaders of the CCF - J.S. Woodsworth, M.J. Coldwell, Tommy Douglas and William Irvine, all from Western Canada, all supported eugenics.

Yet, if you go to the “Our Founders” section of the Douglas Coldwell Layton Foundation – their biographies are a whitewash of history. The foundation claims Woodsworth “became aware of the desperate poverty faced by many working class immigrants, and he expressed this with passion in several books including Strangers Within Our Gates,” when the book promoted residential schools and made sweeping, racist generalizations. The foundation’s biography omits M. J. Coldwell’s participation with the Progressive Party and the 1929 election in Saskatchewan entirely, when the Progressives were collaborating with the KKK. The foundation mentions that Tommy Douglas’ wrote a Master’s Thesis, but is silent on its subject, forced sterilization and eugenics.

This history is also deeply uncomfortable for two Conservative Prime Ministers from Western Canada: R.B Bennett, who was told that he had KKK MPs, and John Diefenbaker, who was a Conservative candidate for MLA in Saskatchewan in the 1929 Election, when the Conservatives were supported by the KKK.

The people who were implicated in these radical politics included Premiers, Members of Parliament, Members of the legislature, Mayors, City Councillors and Church Ministers in 1930s Saskatchewan, Alberta, and BC.

The NDP and Conservatives and their allied parties, including Social Credit, PC, UCP, Reform have dominated provincial politics in BC, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba for decades.

It’s one thing for one political party to cover something up. But what’s happened is that both parties have been guilty, so both have stayed silent about it. They all have a mutual interest in letting the dead past bury its dead, because both the NDP, Conservatives and Progressive parties share the same shameful past – endorsing eugenics and sterilization and collaborating with the Ku Klux Klan to win elections in Saskatchewan and Alberta, and spreading those ideas across Canada.

Now, 95 years later, we’re getting the same arguments, repackaged, because the fundamental ideas have never changed,

When people say that the root causes of crime are addictions and poverty, which they do on a regular basis, they are repeating the same pseudoscientific, eugenicist attitudes, which define the formative ideas that were held and acted on by political parties for decades, and are still there as a conditioned reflex.

These policies have been whitewashed out of history or sanitized as “prairie populism,” when all along it was a radical form of protestant ideology, with national party leaders from the right and left embracing it.

These ideas defined Canada and its politics, and instead of recognizing these repellent ideologies - which were key to the success of many lauded national figures - they are whitewashed out of history.

Coming soon: PART 3: STRANGERS WITHIN OUR GATES

-30-