Inequality and Instability: Marie Antoinette, Cassandra & Babel

On March 7, 2014 - ten years ago this week - I wrote this on my blog

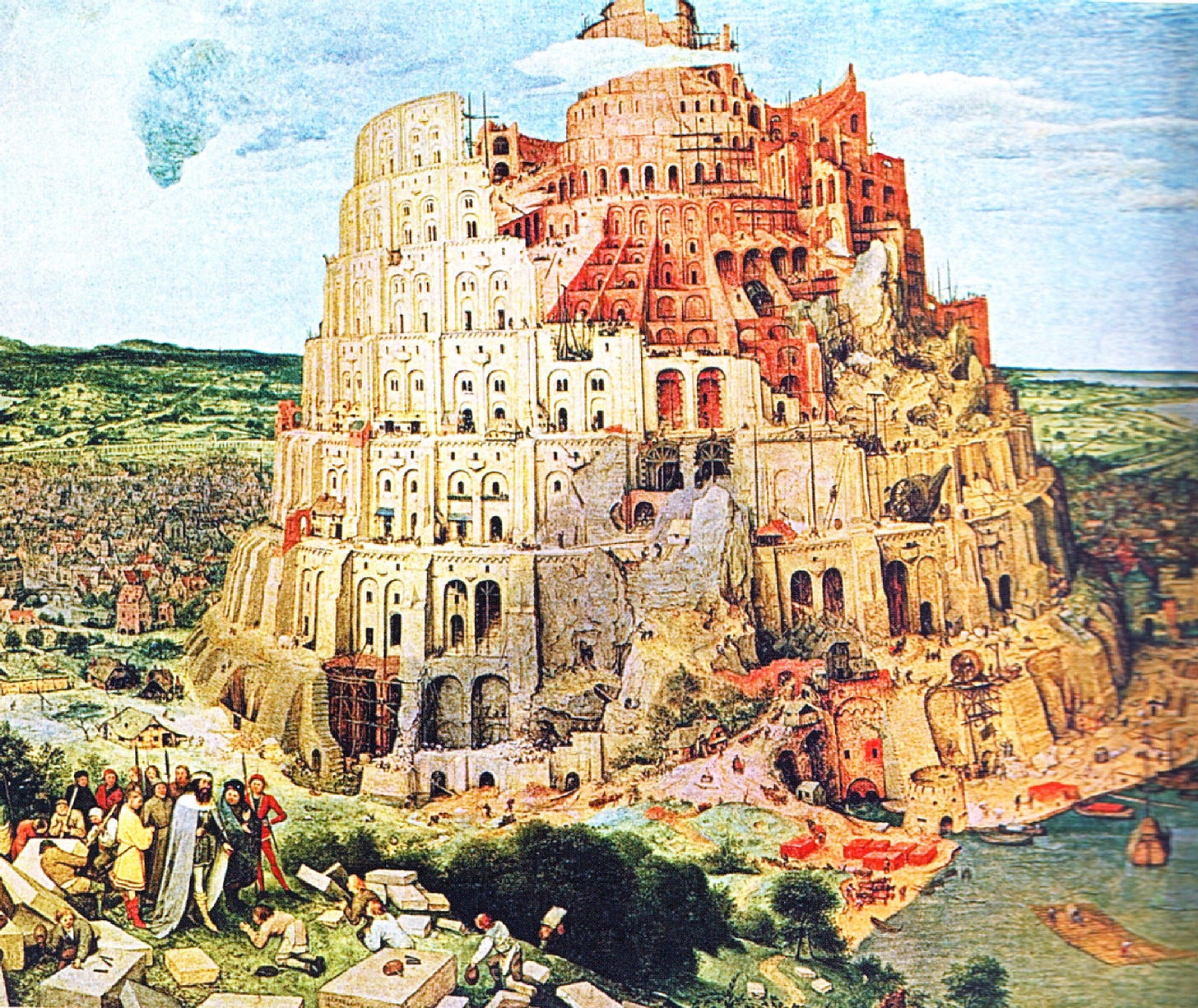

The Tower of Babel by Breugel

March 7, 2014

A French Economist, Thomas Piketty wrote a book that suggests that efficient markets do not redistribute wealth, but tend to lead to greater and greater inequality.

[I think there are good reasons to believe that an “efficient” market will tend to make inequality get worse: in fact, Piketty’s data seems to show that the market can be “efficient” and the rich can get richer even when growth is very slow.]

Piketty expresses concerns that this will just keep getting worse, that liberal democracy was a one-time accident of history, and the only answer is a progressive global tax.

Whether Piketty is correct or not, inequality is real and it seems to be getting worse. While some don’t see inequality as a problem - some see it as a good an necessary thing - it’s often said that inequality can lead to social unrest - not just people on the left, but people like Alan Greenspan.

The reasons for the connection between inequality and unrest aren’t always clear: some people are skeptical. Some even point to the fact that in there have been periods in the past marked by great inequality and instability - feudalism. One difference of course, is that people in those societies had no recent memory of better-shared prosperity, and no concept of democracy.

So why is inequality destabilizing? I think the answer is fairly simple: because elites get dangerously out of touch at the top, and because deprivation leads to greater internal divisions as people struggle over limited resources.

The Marie Antoinette Effect: Elites get Out of Touch

One of the ways that inequality can lead to instability is simply that people who are at the top are oblivious to what is going on. There is the famous example of Marie Antoinette, who when told that peasants were starving because they had no bread, said “Let them eat cake” or “Let them eat brioche.” It’s been suggested that this is a dirty rumour that never actually happened, but whether it is apocryphal or not, it didn’t stop her from losing her head on the guillotine.

Marie Antoinette’s “Let them eat cake” story resonates because it captures the image of a wealthy elite totally out of touch with the suffering of an average person.

In the current debate on inequality in Canada, the US and elsewhere, it has also been hard to get the message across.

I have argued that some of the metrics - like medians and averages - used to measure income may have the unfortunate effect of painting a rosier picture than what is actually happening, especially when a generation of decision-makers, 50 and older, have generally benefited over the last 30 years, while those under that age generally have not.

It is often hard to get people to pay attention to numbers anyway. People would rather rely on personal experience.

Since numbers will depend on the accuracy of the measurement in the first place, is just degenerates into an argument over whatever formulae the data has been strained through to get the final result. Hence the old saw, “Lies, damn lies, and statistics.”

The fact that people won’t pay any attention to statistics is no surprise when they pay no attention to actual poverty and misery in their communities - driving past slums or stepping over homeless people on the way to work.

There has been a lot of “Reductio ad Hitlerium” in the public debate, with U.S. conservative pundits comparing Obama’s alleged “socialist” policies to “National Socialism” (never mind that Hitler was put in place as Chancellor of Germany by conservative polticians). In a letter to the Wall Street Journal, venture capitalist billionaire Tom Perkins, compared criticism of the wealthiest 1% to the treatment of Jews in Germany, (another tiny minority) in Kristallnacht.

Now, Kristallnacht was an organized pogrom by Nazis in 1938 to intimidate and murder Jews all across Germany that resulted in 91 dead, over 1,000 synagogues set alight, 7,000 Jewish businesses destroyed and 30,000 Jews arrested and thrown into concentration camps.

The event that triggered Perkins’ comparison to Kristallnacht was that people smashed the windows at a luxury car dealership in San Francisco, as part of protests across the U.S. at the Trayvon Martin verdict.

200 years ago, during the Highland Clearances, thousands of Scottish tenant farmers were driven off their farms, at a rate of 2,000 people a day so that aristocrats could raise sheep. Many emigrated to North America, others starved and froze to death. The people driving the clearances were oblivious: “The Duchess of Sutherland, on seeing the starving tenants on her husband’s estate, remarked in a letter to a friend in England, “Scotch people are of happier constitution and do not fatten like the larger breed of animals."”

There are always people prepared to deny present and historical misery. This includes the miseries of the Great Depression, where people deny that anyone starved to death (when they did) or discussions of slavery that suggest that it was not that bad, or that slaves did well out of it. Some of these arguments are made at the time of the crisis, and some are made after the fact by economists and historians.

Some of this came to the fore in the 2012 election, when Dan Mitchell, an economist for the Cato Institute, said he hoped that Paul Krugman’s accusations that Paul Ryan’s budget would make life harder for the poor were true.

“To be more specific, I hope Krugman is right in that Ryan wants “to make life harder for the poor” if the alternative is to have their lives stripped of meaning by government dependency. And I agree that it will be “for their own good” if they’re motivated to join the workforce.

William K. Black, who was debating Mitchell, responded by saying

“As an Irish-American I was struck that Ryan’s argument repeated the arguments that Britain’s leaders made when they decided to allow a million Irish to starve to death and another million to emigrate on the coffin ships. The British argued that providing free food (or even food in exchange for brutal work) was unacceptable because it would spur “dependency.” I expressed my disgust for with Ryan’s adherence to the failed theoclassical economic dogma that killed a million Irish and the dogma’s depraved indifference to human life and suffering.”

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2012/08/why-is-paul-ryan-an-irish-catholic-praising-the-dogmas-that-drove-the-great-hunger.html

His response was not well-received.

The fact is that even in times of terrible poverty and upheaval, there is almost always a core of people who are doing all right. Many people in the Depression did not lose their jobs: as long as you were employed, you continued to do fine, get raises, and so on. But for people who were unemployed, it was brutal. That is part of the nature of inequality.

People in private life who are very wealthy may be cut off from the rest of the society. They may literally be walled off, in compounds or gated communities.

But government leaders can also be out of touch for the same reasons - they are often much wealthier than the average citizen. It is incredibly expensive to run for public office and being independently wealthy allows people to take the financial and personal risk of running in a way that others cannot. That is just in a democracy. In autocratic states, the wealthy and powerful may be integrated into the governing bodies.

China, the US and Russia are currently some of the most unequal countries on earth. In the U.S., more than half of congress are millionaires. In China, 70 members of the People’s Congress are billionaires. In 2012, Bloomberg reported that “ The richest 70 members of China’s legislature added more to their wealth last year than the combined net worth of all 535 members of the U.S. Congress, the president and his Cabinet, and the nine Supreme Court justices. ”

In Russia, the expression “oligarch” is well known. It is rumoured that Putin is worth billions. Ukrainian President Yanukovich had to flee Ukraine after pocketing billions from the public treasury.

This inequality has two problems: the wealthy and/or powerful are so wealthy and powerful that they become oblivious, and out of touch with what is going on: what’s more, they can pay to put a distance between themselves and everyone else.

And the people whose lives are going nowhere or getting worse see the wealth and it can lead to popular anger and resentment, especially when there are ongoing and serious economic problems.

It is possible for the people who are benefiting from inequality not to see the connection between what they are doing and others’ misery. They may argue that:

Inequality is not a problem as long as there is still social mobility.

Inequality is not a problem at all, because it makes people even more motivated to succeed (this was made by a partner in Bain Capital in his book Unintended Consequences).

Inequality is not a problem, because it simply reflects the natural order: the cream is rising to the top, and if people are poor it is their own fault because they are lazy or unskilled because they have done nothing to better themselves.

Inequality is not as bad as you think anyway

So, various kinds of denial. The problem isn’t even ignored: it isn’t acknowledged.

The Cassandra Effect: Even if You Speak Truth to Power, they Don’t Listen

Having in worked in political communications for many years, I am aware that some messages are harder than others to get across. This is true of most anyone: people simply cannot take some ideas on board - they can’t integrate it into their thinking because

it is at odds with their pre-existing beliefs,

believing will undermine their worldview, and their place in it

accepting the facts, if true, implies a disaster so great they can’t deal with it.

This was expressed by a political consultant, who said that “it is not enough for a statement to be true - it must also be believable.”

The reactions may be to ignore or deny the information, or have a “taboo reaction” which is what happens when you challenge anyone’s core beliefs (including non-religious ones: scientists get just as outraged when you tell them vaccinations don’t work).

In The Big Short, which was about people who thought the subprime mortgage crisis in the U.S. was going to cause a financial disaster, author Michael Lewis often describes people who are struggling with their beliefs. The people who thought the market would crash questioned themselves because no one else saw the risk. They could not persuade others to see their point of view, because people were quite literally invested in the idea. The people who had poured their money into those investments could not bring themselves to believe that they could fail.

It can be hard breaking bad news to anybody, and speaking truth to power is harder.

The idea of “shooting the messenger” stretches back more than 2000 years, to an Armenian King, Tigranes who beheaded a messenger who brought bad news, with the result that “no man daring to bring further information, without any intelligence at all, Tigranes sat while war was already blazing around him, giving ear only to those who flattered him…“

The more powerful people get, the harder it can be to speak truth to them, because it is not just a question of hurting their feelings: you can be risking your neck. Whistleblowers’ lives are regularly destroyed, whether they are exposing corporate or government corruption. When Lance Armstrong’s masseuse said he had been doping, he falsely accused her of being a drug addict and a prostitute.

There is also the fact that people do not want to bite the hand that feeds them: this is true of both government and the private sector. Rich and powerful people are rich and powerful because they own companies (sometimes media companies), which means their business decisions can make or break people. They may be generous philanthropists, which means that organizations rely on their good will.

They are called “wealth creators” and “job creators” (and some are). From their perspective, they are providing jobs to the jobless and money to causes in need.

Because they are in this position, they will be surrounded by people who are very nice to them and who will cajole, flatter and beg in order to win their favour. This means that criticism may come as a shock.

When it comes to political power, because politics is filled with so much posturing, exaggeration and propaganda, a legitimate, truthful criticism - or warning about a bad policy - may be dismissed, like the boy who cried wolf.

This phenomenon was embodied in the person of Cassandra in the Greek myth of the Trojan wars. Cassandra is given the gift of being able to see the future, but also the curse that no one will believe her. As a result, she goes insane.

Many people will refuse to believe a warning. The only way they can be persuaded that it is if actually happens to them, in which case it will be too late.

Why the US may be slightly different

People may always have been cynical about the U.S. (or have grown cynical) especially since 9/11 because of the many intrusions on personal freedoms that have come about: NSA surveillance, “extreme interrogations,” rendition, and the dubious legal status of people in Guantanamo Bay, CIA Black sites, drone killings, suspensions of legal rights. (that is quite aside from conspiracy theories that suggest more and worse).

They will point to China or Russia and ask whether the US is worse, or any different.

I happen to believe the U.S. is different, in part because it still has elections that, though very heavily influenced by money, gerrymandering, and a host of other abuses, still hold politicians to account. And despite concentration of media ownership, partisan propaganda and more, US Citizens have largely unfettered access to information on the Internet and they can say practically anything about the President without being disappeared. This is not true in China or Russia.

This means that I suspect the U.S. has a degree of flexibility built into its system that may be mistaken for weakness, in comparison with the rigid stiffness of Russian or Chinese systems.

For democratic vs autocratic systems there are advantages on each side. For China and Russia, it means they can act quickly and strike first. This is an important strategic advantage.

The benefit of democracy is that there is always someone else training up and vying to be the leader: either competing political parties or a politician. That means when one party or politician fails, someone else is ready to step in.

But in the absence of a free press, and freedom of speech, and an opposition that can speak its mind, China and Russia also have to use different methods for acquiring information on what is happening - surveillance being one.

It means two things - that leaders in the US are more likely to get an honest earful, but also there will also be a bunch of garbage that gets said. The challenge here (as in life) is to separate the signal from the noise.

One of the major perceptions and themes is that the US is in decline and that China and Russia are on the rise, and, more specifically, that Obama is a weak president, that the U.S. is crippled by debt, etc.

This is a perception that is very much fed, and pushed, by American critics of Obama, who have sought to paint him as inferior (in part as a dogwhistle subliminal message to racists).

Plenty of people around the world hate the idea of the US either as an empire or as a Global police officer, and the perception of weakness can make either the Chinese or Russians opportunistic. They will be willing to risk a military intervention because they think there will be no consequence. That may well be what Putin is thinking as far as Ukraine is concerned.

You may ask, “Why am I dragging China into this?” Because of a report from Davos about comments made by a respected Chinese businessman, who suggested that China might simply seize some worthless islands that have been the source of a long-standing dispute because Japan would not dare respond and neither would the U.S., and it would finally show everyone who’s boss - China.

http://www.businessinsider.com/china-japan-conflict-could-lead-to-war-2014-1

The Chinese professional suggested that this limited strike could be effected without provoking a broader conflict. The strike would have great symbolic value, demonstrating to China, Japan, and the rest of the world who was boss. But it would not be so egregious a move that it would force America and Japan to respond militarily and thus lead to a major war.

Well, when the Chinese professional finished speaking, there was stunned silence around the table.

The assembled CEOs, investors, executives, and journalists stared quietly at the Chinese professional. Then one of them, a businessman, reached for the microphone.

"Do you realize that this is absolutely crazy?” the businessman asked.

“Do you realize that this is how wars start?”

“Do you realize that those islands are worthless pieces of rock… and you’re seriously suggesting that they’re worth provoking a global military conflict over?”

The Chinese professional said that, yes, he realized that. But then, with conviction that further startled everyone, he said that the islands’ value was symbolic and that their symbolism was extremely important.

Recall that the First World War was triggered by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand with the goal of separating part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. The fight over the territories escalated and triggered a series of treaties that resulted in millions dead.

One element that sparked the Indian Rebellion of 1857 was due to the fact that cartridges the British supplied for new Enfield rifles had to be bitten to release the powder (hence the term “biting the bullet”) and in were greased to make them easier to load. The grease used was either beef tallow or pork lard. The soldiers doing the biting were all either Hindu - who don’t consume beef - or Muslim, who don’t eat pork. At a stroke - and against the warnings of East India Company officials - this managed to violate the religious sensibilities of 300,000 armed soldiers.

In the First World War, the obliviousness of generals to the reality of the front sent millions to their deaths. At the 1916 Battle of the Somme, 1,000,000 men died, with 60,000 British casualties on the first day alone. That did not stop generals from sending soldiers across mud-sodden fields straight into machine gun nests for months.

The reason leaders can think like this is precisely because they are living a life where they are cut off from consequence, and they have always been able to get away with whatever they want.

This is a very serious problem and it is not new. In the Art of War, Sun-Tzu wrote that “foreknowledge cannot be elicited from spirits; it cannot be obtained inductively from experience, nor by any deductive calculation. Knowledge of the enemy’s dispositions can only be obtained from other men.”

The Tower of Babel & Desperation and Division

Extreme inequality means that there is a growing gulf between the “rich” and “the rest”. It also tends to create sharp divisions among “the rest” as well.

When people are attacked, they may pull together, but do so in a tribal fashion: not into a collective mass in agreement, but splintering into harder groups.

Battlelines are drawn around group identities, which may be defined by anything that brings people together as a group: ideology, social status, religion, ethnicity.

We like the idea of people pulling together in tough times: but people also do so by pulling apart at the same time. Larger groups will fracture, into smaller, tighter factions. In debates after the attacks of 9/11, the “blame” could just as easily fall on traditional opponents rather than the actual perpetrators. Conservative commentator Mark Steyn blamed “the West’s moral failure” for the attack, as did Pat Robertson.

This is like the myth of the tower of Babel - that after coming together to build a tower to the heavens, which was arrogance in the eyes of God, that God scattered the people and confused their language so could no longer understand one another - just “babbling.”

Literally-minded scholars assume that there is a direct reference to a particular tower. But the phenomenon of people splintering into factions is real and contemporary.

This was clear in the U.S. between the Occupy and Tea Party movements both developed around 2008. They are seen as political opposites but in some ways are two sides of the same coin: both were opposed to government bailouts of the economy.

Occupy and the Tea Party are opposed not only to each other, but to the elites on the right and left with whom they would otherwise be aligned. Occupy targets Wall Street Democrats, and the Tea Party attacks RINOs (Republicans In Name Only), and both reject “government” as a solution, because they view government as having been co-opted.

While you may not agree with either Occupy or the Tea Party, they should be recognized for what they are - groups of people who at the grassroots level are economically distressed who don’t think government works for them. (The Tea Party in particular was quickly hijacked by monied interests who want to use the credibility that comes with a grassroots movement in order to turn them into “astroturf” organizations. It sometimes backfired.)

As things get worse, the need to find solutions gets more urgent, but the fight over how to do it gets more pitched. People can’t achieve a consensus.

There can be a basic agreement on a goal - better jobs, a better economy, but a bitter political and ideological split about how to achieve it - left vs right, more taxes and more government spending, or lower taxes and less government

People who are suffering or are desperate are usually easier to enlist to a cause. If resources (or money, or jobs) are scarce, people don’t care about political leadership that is fair to everyone: they want someone who will be unfair, as long as it is unfair to someone else. It becomes easier for them to dehumanize an opponent or enemy, or traditional rivals as much of a human being: they simply stop caring as much. And if you have been put through suffering as the result of others, you are likely to welcome an opportunity for revenge.

John Maynard Keynes’ economic policies have been in and out of vogue. But in 1919 he quit the negotiations for the Treaty of Versailles, saying that the penalties being imposed on Germany were so harsh that they would likely lead to another war. He was right.

Reparations payment created hyperinflation in Germany. In the 1920s, Belgium and France stopped taking payment, and sent troops to the Ruhr Valley in order to lay claim to something of actual worth: coal and steel.

Many think that Hitler came to power after this period of hyperinflation: in fact, it was after a lengthy period of austerity.

All of this makes the situation in Europe (and Russia, and China, and the United States) politically unstable and perilous over the longer term. There are millions in Europe who have been living under forced austerity and deprivation because of the excesses of others - bondholders and government officials. Violence, instability and war is an opportunity to take revenge.

As situation becomes politically polarized, extremists crowd out moderates. Moderates will tend to argue for broader benefits to be shared among the greatest number (especially when the hyperconcentration of wealth may already arguably fuelling the crisis). But extremists, with their narrow focus, can appeal to an intense few: their certainty will make them appear strong. So there will be communists on the one hand and fascists on the other, and liberal democrats (if there were any in the first place) will be driven out.

Putting out the fire with gasoline

The difficulty in dealing with either unrest or inequality in the current global economic and military situation are many.

One is that we have gone through three decades of “neoliberal” ideas during which time the role of government has been described mostly in terms of being a stick jammed in the spokes of the otherwise smoothly spinning wheels of the global marketplace.

So, despite evidence that the market itself, or globalization may be creating greater inequality, and suggestions that government has often played not just an important role, but the central role in ensuring prosperity is better shared, the answers to problems that may have been created (or are aggravated by) less government, lower taxes, less regulation, and globalization, is more of the same.

Settling disputes by negotiated, legal, diplomatic means is far less costly than war. Elections are always less costly than riots, revolts and revolutions.

Churchill said “It is better to jaw-jaw than to war-war” and Sun Tzu said that the acme of war was not to win many battles, but to achieve victory without fighting at all. As a result, he argued, the truly great strategist would never get credit for what they had achieved.

This has been reflected in the number of ways in which democratic governments, and democratic input, has been restricted.

One obvious way is trade deals, which place limits on what governments (especially lower levels of government) can do to protect industries, create jobs, or enforce environmental regulations. If a local, state or provincial government wants to impose a moratorium or ban on fracking because they are concerned about environmental or health effects, they will face a lawsuit. If they want to hire locally-owned companies, with local employees, they will not be allowed to.

Another is that there has been increasing growth in executive power, with Presidents, Prime Ministers and their Cabinets taking over decisions that once would have been debated in public and voted on by parliaments or congress.

One way this has happened in Canada is that decisions that once would have required debate and change in law are converted to regulations instead. Once this happens, changes in regulation can be made, in private, by cabinet or Ministers alone. This has been happening for decades.

In Canada, there has been a hyperconcentration of power and control in the hands of the Prime Minister’s office - a position that does not even exist in the Canadian constitution.

As for the U.S., there was a concerted effort under the W. Bush administration to gather more power to the executive. Only congress has the power to go to war, but President Obama has waged a nearly personal war when it comes to drone attacks.

As inequality gets worse, we can regularly read about the exploits of rich celebrities or the salaries of CEOs. As Wall Street does fine while everyone else grinds along, it creates the impression that politicians work only to enrich themselves or the wealthy. There may be the temptation to think it has always been this way, except that throughout the 20th century everything from public pensions to universal health care and education have all hugely improved and enriched the lives of millions.

If people think the game is rigged against them, they will not bother to participate.

There are two other effects - one is the manipulation of the elections and the democratic process in a number of ways that undermine the legitimacy of the government.

In the U.S. there was the debacle of the 2000 election and the election results in Florida. There have been ongoing efforts to prevent people from voting or to manipulate the results through gerrymandering, or redrawing the borders of voting districts in order to obtain a particular result. The US budget and government shutdown/showdown in October 2014 was driven in part by Republicans elected in gerrymandered districts who cannot lose. Gerrymandering (by both parties) makes a big difference: in 2012, Congressional Democrats won the popular vote, but more Republicans were elected.

In Canada, since 2006, there have been a number of convictions under campaign finance laws, mostly by the governing Conservatives: overspending, forged invoices, attempts at gerrymandering, robocalls misdirecting people to nonexistent poll locations making it harder to vote, and now a bill that will make it significantly harder to vote.

In all of this, the concept of a liberal democratic welfare state is increasingly considered a relic of the past, and that the possibility of a country exercising national economic sovereignty is considered “quaint” in today’s “globalized world.”

Part of the reason for motivation for setting up a global banking system in the wake of the Second World War. Free markets would create a degree of interdependence that would reduce the likelihood of war in the future.

I think this is a mistake, for a number of reasons. One is that globalization itself is considered to be one of the major drivers of inequality. Alan Greenspan has argued that globalization - not capitalism - is the cause of growing inequality. (Though he has been wrong about lots of things before).

If that is the case, then it could be argued that globalization, by driving inequality, is making the world less stable, not more. Middle-class jobs in developed countries are being lost, and wages pushed down, as a result of competition from products and services in China, India and elsewhere. This is not so much job creation as a shell-game: entire factories are shifted to another country, while ownership stays in place. This would have been inconceivable to many of 19th century political theorists.

China, India and Russia have all grown enormously and are more prosperous, but the benefits in all of these countries has also overwhelmingly gone to a few at the top. In China, almost all of the growth has gone to the top 20% of the population, and half of the population - 700-million people - are no better off and are still living in abject poverty. This is clear from China’s ranking in per capita income: 87th.

That means growing the risk of growing unease within those countries - though when there are large numbers of the poor, they may have no resources to stage an uprising. This is not true of the bourgeoisie: and almost all revolutionary leaders tend to come not from poor families but from middle- and upper- middle-class families. This is true of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Fidel Castro, Osama Bin Laden, Al-Zawahiri and Che Guevara (to name a few). (It is also true of the American Revolutionaries).

But the benefits of trade linkages always come with risks. Tying your fortunes too closely to another country has benefits, but the risk is that if it goes down, it can drag you with it (please see: Greece, Spain, Ireland, and the Eurozone). A single global market means there are no barriers to global market shocks. In the response to the invasion of Crimea, there was preliminary praise for globalization and the markets, arguing that markets acted much more quickly to punish Putin than governments could. The Russian stock market was down: but so were markets around the world. (The German stock market did pretty well during the Second World War until about 1943).

This could also be seen as a crisis of globalization. The tensions in Ukraine originally exploded because Yanukovich decided against allying himself with the EU and opted for closer ties with Russia instead. Ukraine being forced to choose between one of two common markets: the EU, or a customs union with Russian and other former Soviet states. The perception is that Ukraine has to choose either one imperial master or another.

The assumption is that the markets will constrain Putin and Russia. But the opposite is true: Putin supplies Europe with energy, and Russian Oligarchs have filled British banks with their riches.

The result, as Ben Judah recently reported in the New York Times, is that UK will oppose any effort to seize or freeze Russian assets because it might affect the UK’s banks. As he put it, “Britain is ready to betray the United States to protect the City of London’s hold on dirty Russian money.”

Put it this way: James Bond is now working for SPECTRE.

At least one commentator has said that the Crimean conflict is not a new Cold War, because it is not ideological: it is only about military and economic power. This is to miss the point: all wars are about military and economic power. The ideology just defines the groups who are in conflict.

Ultimately, inequality results in divisions, into an us vs. them that is dehumanizing and makes it much easier to do things to others (or treat people like cannon fodder) in a way that we would never do to one of our “own.”

Sadly, articles like these won’t do much to change the minds of anyone to act on either inequality (or instability). It will not be until things go horribly wrong that people will realize their folly.

The fact is that inequality is not an inevitable economic outcome: it is a political choice. We can also choose less inequality, and there are compelling reasons to do so.

D F Lamont

March 7th, 2014 1:14pm