Shot and Left for Dead: Frank Bastin’s Account of the First World War

My Great-Uncle, fought at the Somme and Vimy, before being shot and left for dead

From the Manitoba Historical Society Biography of Frank Bastin

http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/people/bastin_fm.shtml

Born in the Rural Municipality of Louise on 25 December 1896, son of Charles E. and Mary D. Bastin, he was educated in Winnipeg public schools. After service in the Cavalry Cadet Corps, he enlisted in the Canadian Army and served in the infantry during the First World War. He was seriously wounded, and reported missing and presumed dead, in 1918. After recuperating in England, he returned to Winnipeg where he entered the Manitoba Law School, graduating in 1921. He practiced law with J. S. Lamont and later joined Traders Finance at Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

During the Second World War, he went overseas as General Manager of the Canadian Legion War Services in London, returning to Winnipeg in 1945 to practice law with the firm of Andrews, Andrews, Thorvaldson and Eggertson until 1959, when he was appointed a judge in the Court of Queen’s Bench. In 1971, he began serving as a Supernumery Judge in the trial and appellate divisions of the Federal Court of Canada.

He was an active member of the Conservative Party, the Masons, the Anglican Church, the Winnipeg Winter Club, and the St. Charles Country Club.

He died at Winnipeg on 15 October 1986 and was buried in St. John’s Cemetery.

The First World War

From an early age I had the intention of becoming a doctor, so when war was declared on August 4th, 1914, I naturally joined the militia unit of the Canadian Army Medical Corps. I was born on December 25th, 1896, so I was then 17. However, the pre-war members of the unit had already departed for Valcartier in Quebec when I enlisted and there seemed like no likelihood of any more more men being needed for overseas service for months, and in the meantime there was only first aid training in the evenings. I soon tired of this comparative idleness. A friend, Cunliffe Powys, suggested that I should spend the winter on the farm near the town of Wawanesa which his father had bought on his retirement as a civil engineer with the C.P.R., to harden myself for the rigors of military life.

As I had been ill in the spring of 1914 I decided that this was a good idea so I spent the winter at the farm doing the winter farm chores, consisting of cleaning the stable daily, the pig-pen once a week, spreading manure on the land with a manure spreader and bringing ice from a small pond to melt to provide water for the stock. This was necessary because the well had become dry. The Powys’s hoped to remedy this by deepening the well so a well digger was hired.

He brought his equipment of a tripod and large bucket and spade. Cunliffe and I assisted by turning the windlass to raise the dirt as the well digger excavated it. On one occasion as the well digger made his descent after lunch he shouted in a panic to be pulled up and he explained that he had seen a ghost at the bottom of the well. Unfortunately for the sake of psychic research, it turned out on investigation that a turkey had fallen into the well and was the cause of his fright.

I do not recall when I decided to become a fighting soldier instead of a stretcher bearer, but when I returned to Winnipeg in the spring I did not return to the Army Medical Corps depot but applied to enlist in several fighting units, only to be told repeatedly that there were no vacancies. When I went to Minto Armories which housed the 44th Battalion there was one vacancy but two were applying - myself and a middle-aged man who had served in the Mounted Police. Dr. Strong, the battalion doctor, no doubt after comparing our physiques, accepted the older man so my efforts to become a fighting man once more suffered a setback. This was not the last I saw of this rival. He crossed my path on a later occasion. This rebuff made me even more determined and I decided that if patriotism was ineffectual in my effort to serve my country I would try the power of influence.

A lawyer well known to my father was in command of the unit of the Army Service Corps, which, although not a fighting service, was part of the armed services and an appeal to him was successful.I was now a soldier, and due to the which numbers were allocated to the various services , I was given the number 3279 suggesting a very early enlistment.

When I went into Winnipeg to enlist Cunliffe travelled to St. John’s, New Brunswick where his family had come from, to join the 6th Canadian Mounted Rifles. Canada recruited many mounted regiments due, no doubt, to recollections of the Boer War, but only one, the Fort Garry Horse, along with the two permanent force cavalry regiments, the Lord Strathcona Horse and the Canadian Dragoons, served in France on horseback. I was interested to learn that Cunliffe won the welterweight boxing championship while in training in Valcartier camp.

Cunliffe and I had been about equal in boxing skill as members of All Saint’s Boxing Club which had been organized by the English curate who, in his ministry in England, had found that the occasional giving or receiving of a black eye was a good introduction to the rough members of his congregation. I later learned that Cunliffe had been killed in the German attack in Ypres salient in June 1916, which caused the 46th Battalion to send me as a reinforcement to the 3rd Battalion.

On May 15th, 1915, our unit was sent to Camp Sewell, now Hughes, to prepare for the opening of a large training Camp under canvas. Our first duties were to look after a large number of young horses fresh from the range which had been bought to pull our transport wagons. They were so high spirited that it was dangerous to go near their hind legs, and their training to saddle and to pull a wagon provided excitement for weeks. I had had some experience with horses but not such wild animals as these so I welcomed being assigned to the mechanical transport section. I had never even sat in a car in my life but I was given the duty of driving an old worn out White truck delivering bread to the various units. Fortunately there was little traffic in camp so I was able to learn to control my rattle-trap without accident.

Even more of a shock than being told to drive without training were the men I was associated with in this section. Almost without exception they had been in the taxi business in Winnipeg. I found my companions friendly but they could talk about nothing but whore houses and their charming inmates. Even at this distance of time I can recollect the shock it gave me to realize that my companions had been associating on friendly terms with prostitutes. Of course, the community of interest which brought them together was obvious. Winnipeg was the natural resort of the railroad builders, lumber jacks, harvesters and miscellaneous workmen who had accumulated a stake and were in a hurry to start spending it. Naturally their first port of call was a brothel, and at that period such houses were segregated in various parts of the city, Taxi drivers derived a large part of their business from such spendthrifts, and it was merely good business for the ladies of pleasure to be on friendly terms with taxi drivers by providing them with free drinks and free copulation.

My conception of a prostitute was a creature so depraved and shameless a s to be incapable of normal human feelings. I could not imagine that most of them chose their trade as a lazy way to make a good living. That one of them at least had normal feelings was shown by the fact that she married one of the taxi drivers after he had enlisted and followed him to England. I gathered that the relationship was ardent and sincere but it did not interfere with her normal avocation.

We had not been in camp long when my rival, the former mounted policeman, turned up as a member of our unit. Presumably he had been turfed out of the 44th Battalion. In short order he became the batman of the commanding officer and apparently was giving satisfaction when the major caught him using his toothbrush. So far as I know this is not an offence under the King’s rules and Ordinances for the armed forces but it was considered sufficient grounds to relieve him of his duties as batman and to summarily dismiss him from the service.

At that stage of the conflict the honour of serving one’s country required

not only influence but a high standard of personal hygiene.

As O/C of bread delivery I became well acquainted with the two butchers who were responsible for the delivery of the meat ration of one pound per day per man. They had been trained to their trade in England and followed what was apparently a trade tradition of shaving their hair off in the summer and anointing their bare scalp with mutton fat. As the volume of meat to be cut up expanded the meat depot was placed under the command of Colonel Mullins, an old time rancher with influence with Sam Hughes, the Minister of National Defence. Another political appointment was a man called Hughie Green who was placed in charge of providing fish to the forces. He later turned up in England but was unsuccessful in forcing fish from Canada on the troops. I continued delivering bread until our unit was sent overseas in July 1915. I was never out of camp until I went on my embarkation leave. The nearest town was Carberry and it was a long dusty walk from camp and offered no particular attraction.

However I do not recall being bored althouqh there were no recreations

in camp other than a swimming pool. My explanation is that troops who are working hard do not need to be provided with entertainment.

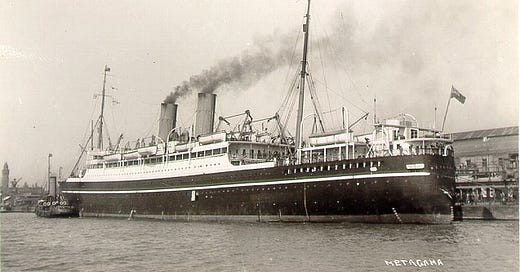

We sailed from Montreal in the CPR ship the Metagama, and had normal summer weather, but unfortunately my bunk was at the lowest level in the bow of the ship. Whether the foul air affected me or not, the tremendous arc travelled by the bow of the ship did and I spent days lying on deck, too empty to vomit but frightened of taking even a drink of water. If I had thought about the possibility of facing such an ordeal on my return voyage I would have have determined to give my life for my country rather than endure it again.

When I set foot on the pier at Plymouth, a surface that neither heaved nor rolled nor pitched, I needed no convalescence. In fact I felt very well, which has made me believe that there is benefit in the Swedish practice of starvation diets. What I noticed particularly about England on my first view was the very efficient toy train in which we travelled through Devonshire, Somerset, Wiltshire and all the other beautiful counties to Folkstone. The garden-like scenery of hills and dales, woods and hedges appeared to have been designed to produce the most artistic effect. Our destination was a brick military barracks at Sandling which appeared to be filled with a crowd of idle men who kept out of sight except at meal times.

Among them were some who had been wounded at the 2nd battle of Ypres and who relived their experiences in their dreams, shouting and crying out in a frenzy of excitement. I have never seen any other men affected in this way and I conclude that the open warfare in this battle made a greater emotional impact than the normal routine of trench warfare.

I was designated a second driver and I spent many hours seated beside the driver of an army truck navigating the narrow, winding English lanes. Since we were within walking distance of Folkestone we had plenty of opportunity of enjoying the attractions of this pleasant seaside town. One of my companions was a former Eaton’s manager named Daly who was older and more socially experienced than I was, and by his charm and boldness he soon made us acquainted with two attractive local girls. My companion was the daughter of the harbour master, and while I was stationed at Sandling I spend many evenings in her company. Later when I was stationed in Hampshire she she arranged to take her holiday in in London when I was there on leave. I came to realize that she was seriously hoping to marry me although I had repeatedly told her that I had no means of supporting myself so I finally broke off our relationship which had been very pleasant but quite platonic.

For the time being my plan to become a fighting soldier was stalled, as I knew of no unit to which I wished to be transferred. This problem was solved when I met a friend called Johnson, whom I had known when I was in Ninette Sanatorium where I had spent several months early in 1914. I was only suspected of t.b. but his disease had been confirmed so he must have concealed this in order to enlist. He was in the reserve unit of the 44th Battalion, and I promptly applied to the regimental sergeant-major to complete an application for transfer. I was surprised that this hard-bitten soldier spent several hours trying to convince me that a transfer to an infantry unit was tantamount to suicide.

I persisted and eventually the papers were completed and presumably dispatched to Head Quarters in London.

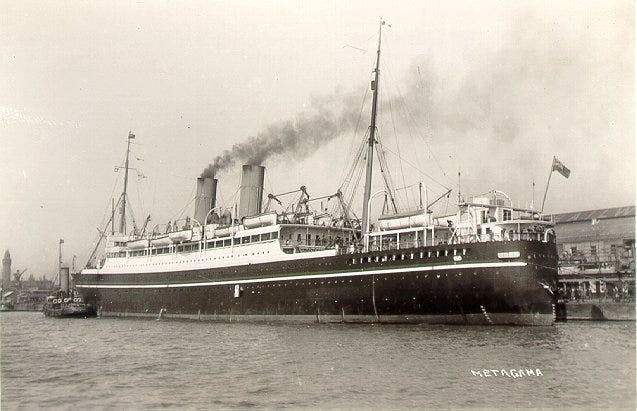

But once more fate intervened. I suppose that someone in authority discovered that our barracks had become the hideout of scores of soldiers who performed no duties, and called for a muster parade. Everyone had to be identified, classified and disposed of. I found myself assigned to a unit called Railway troops to be stationed at Bramshott Camp in Hampshire.

The unit consisted of a lieutenant, 3 sergeants, 5 corporals and 2 privates, myself and the despatch rider. Our duties consisted of checking the bags of bread, sides of beef and miscellaneous foodstuffs which formed the rations of the camp as these were delivered by train to the nearby towns

of Haslemere and Liphook two days a week. During the rest of the week we were left to our own devices. Lack of money was the only limitation on our visits to London. Apparently this move rendered my application for a transfer to the 44th Battalion abortive and I heard no more of the matter.

I was in England for several months before getting in touch with my relatives. The first ones I met and the ones I saw the most of were the Halfords, the family of my father’s sister, Gertrude. She was married to Will Halford who had inherited a jewelry business at 41 Pall Mall. The clientele was mainly members of the landed aristocracy and these had suffered severely from the inheritance taxes imposed by the Lloyd George budget of 1911 so this business gradually declined and some years after the end of the war was closed. When I first visited them the family lived at Woking. One daughter had married and gone to South Africa and I never met her. The others were Harold who had a Scottish wife, an albino Rex and Claude who were still bachelors, Beatrice, about my age and Gwen who worked during the war as a farm girl and later became the manager of a farm in South Africa.

When I first visited them at Woking, Rex insisted on showing me Windsor Castle by means of a sulky, that is, two wheels and a seat attached behind his bicycle. I recall that it took two hours and must have been a very tiring ordeal. Rex subsequently became a clergyman. I believe that Claude and Harold stayed with the business and Beatrice met a Canadian, Charlie Elsey, who had been gassed at the 2nd battle of Ypres and was employed in the London pay office of the Canadian army, married him, and came with him to Winnipeg where he became the manager of the Manitoba Club.

Not long after my first visit the Halfords moved to an apartment on the sea front at Brighton on the advice of their doctor who told them that it was necessary for the health of either Uncle Will or Aunt Gertie, or both, to change from the dank and heavy air of Woking for the invigorating air of the south coast. My aunt was a very charming and lovable person but I formed the impression that she was impractical. She undertook the task of acquiring living room furniture for their apartment and attended an auction for this purpose, but unfortunately the first item to be offered was a grand piano which so took her fancy that she spent the entire amount allotted to buy this one item.

The Halfords were very kind to me so I naturally visited them as often as I could. I also met the family of Matthew Shaw, a tea merchant who resided at Muswell Hill in north London. He had married an aunt of my father and he had three children by his first wife, Phillip, Bernard and Gwen. Gwen was a middle-aged spinster who had an intimate knowledge of London and she gave me a conducted tour of all the important places, such as the Tower, St. Paul’s, Westminster Abbey, the British Museum and Madame Tussaud’s.

In due course I visited my mother’ s relatives at Leek in Staffordshire.

There was the family of my uncle Tom Flanagan, several members of the family of my maternal grandmother, the McDonoughs, and my cousins, Molly and Kathleen Hudson with whom I stayed when in Leek. The town itself is not attractive but it is surrounded by beautiful countryside. We took a walk to see Lake Rudyard, a man-made but attractive reservoir, and on another occasion drove with friends of the Hudson girls for a picnic in Dovedale, a celebrated beauty spot in what is called the Peak District.

This easy-going life did not lessen my determination to see action. In the early months of the war, the anxiety of would-be soldiers was that the war would end before they could participate but by this stage this was no longer a serious concern. However I could not see myself spending the war in such an indolent fashion so when I met Bill Davidson who had been my camp leader in the Y.M.C.A. camp at the Lake of the Woods and who was now a lieutenant in the 4th Battalion, I promptly explained my problem and he was good enough to have his 0.C. Lieutenant-Col. Snell make an application for my transfer to his unit. So, after about 10 months of effort I finally became a soldier.

The 46th Battalion was part of the 4th Canadian Division which was being prepared to join the other three Canadian Divisions in France. It had been recruited in Regina so I knew no one except Bill Davidson and as I was not in his company I saw nothing of him. My companions were a fine lot and I enjoyed the hard training. In contrast to conditions in the Second World War, the Canadians in training caps in England had little contact with the civilians in the nearby towns, nor did they have or appear to need any laid-on entertainment. I did a little boxing in the platoon hut on rainy days and entered the unit field day and won the high jump and came second in the mile. Plans had been made to hold a 4th Division field day, so about 20 of us who had shown some athletic ability were relieved of normal training and spent our days in running suits trotting along the beautiful country lanes. The English spring is a charming season and I found this activity delightful.

However, good things never last and a sudden and murderous attack by the Germans in the Ypres salient followed by a costly counter-attack to regain lost ground created a demand for a great many reinforcements. My recollection is that the battalion retained all officers and n.c.o.’s but that the privates were allowed to volunteer to go as reinforcements to France and most of them did so. For some obscure reason, a condition of being accepted for service in France was to pass through a dental clinic. The hutful of dentists had a field day making extractions and they filled bucket after bucket with blood and teeth. In this emergency there was no time to waste on fillings, and if there was any doubt about a tooth, out it came. Strong men faced with this shambles turned pale but no one held back since a refusal meant no trip to France.

We made the trip to Boulogne at night packed like sardines in a small steamer, and we were so sea-sick that we vomited on each other but as everyone was in the same condition no one seemed to mind. The general policy of the Canadian military authorities was to reinforce units in France with men from the same part of Canada where the unit had originally been recruited. But apparently this policy was not inflexible in cases of urgent need so about 100 of us from the 46th Battalion originating in Toronto in the First Canadian Division, and about the same number were sent from the 44th Battalion which had been raised in Winnipeg.

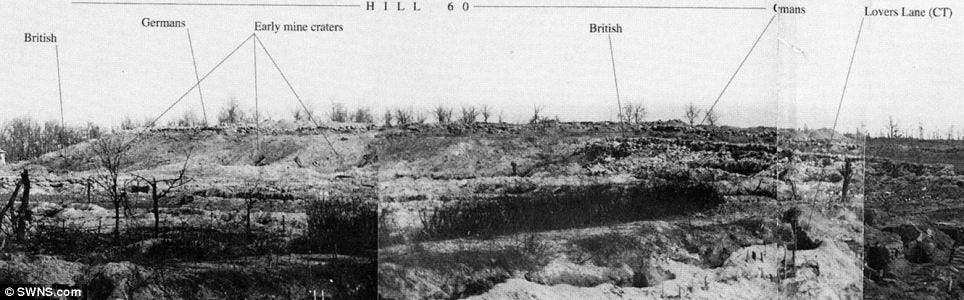

We found the remnants of the 3rd Batallion bivouacked in a muddy field sheltering from the rain under make-shift tents of groundsheets, tired, unkempt and dirty. They had counterattacked to regain a foothold on the ridge which surrounded the Ypres salient and had suffered heavy casualties. Apparently when the war of movement became one of the trenches the Germans selected high ground for their defensive positions, giving them clear observation of the rear areas held by their opponents. This was the situation at Vimy Ridge and the Ypres salient where it was impossible to move troops or supplies to the front line in daylight.

At the outbreak of the war on August 4th, 1914 the Germans swept through Belgium in a great encircling movement designed to overwhelm the French and to end the war in a few weeks. It failed because the right wing of the German advance became overextended and was thrown back by a French and British counter-attack.

From then on until the closing months of the war which ended on November 11th, 1918 with the capitulation of the German army, the war in Europe consisted of attacks by one side or the other on their opponent’s land fortifications which stretched from Switzerland to the English channel.

On the side of the allies these fortifications were mainly on the surface in the form of trenches supported in places with sandbags. The Germans reinforced their surface trenches with deep dugouts which were protection against shell-fire and concrete machine gun posts.

To limit the effect of a shell exploding in a trench and to protect against enfilade fire the trenches were not dug in a straight line but had alternative bays and traverses. The deadly power of machine guns against attacking soldiers led to a great increase in the use of artillery, which made short advances possible by flattening trenches and destroying wire entanglements and covering the advancing troops with a creeping barrage which disorganized the defenders. The British actually invented the answer to the power of the machine gun by building a moveable fort known as the tank propelled by crawler tractors, but it was introduced prematurely and was not perfected until after the end of the war.

Trench life varied from one front to another and certain elements were constant - mud, cold and discomfort in varying degrees and a constant feeling of nervous strain even when on a quiet front. In the Ypres salient where the forward trenches were in places less than 100 yards apart there was the fear that at any moment all hell would break loose, and periodically it did. Every trip to the front line on that front had casualties from sniping. Raising your head above the parapet or forgetting to duck when passing the low spot in the side of the communication trench meant nah poo, toodle oo, good-byee. In the winter a common ailment was trench foot caused by wet and cold and poor circulation so every platoon officer was ordered to personally see that his men rubbed their feet daily with whale oil.

The day in the trenches commenced at stand-to just before dawn when every man stood ready for action as this was the most suitable period of the day for an attack. At that time there would be enough light for attackinq soldiers to see their way but not enough light for accurate rifle fire. It was then that we got our daily rum ration, usually a nosecap filled with liquid fire. Straight, undiluted rum may not be very palatable but it is a powerful stimulant and it produced some wonderful arguments. With the coming of daylight the troops stood down and for the rest of the 24 hours it was two hours on duty and four hours off. There were fatigues such as repairing the trenches but most of these such as bringing up sandbags and other supplies and strengthening the wire entanglements were done at night. Both sides used trench mortars which kept everyone on the alert. The Germans had two types, a small serrated shell called a pineapple and a large cannister filled with explosive which was thrown high in the air by a projector which the Germans called a ninnenwerfer. As the cannister was a long time in the air it could be dodged so when we heard the dull thud of the projector we tried to guess if it was going to land in our section of the trench.

We took our duties quite seriously, and when out of the line spent hours trying to improve our bomb throwing. The proper method was to lob the bomb high in the air with a straight arm motion so that it would reach its target just before the expiration of the five seconds taken by the fuse to reach the detonator. We also did some practicing with live bombs and had several men wounded when the bomb exploded prematurely due to some defect in its construction. One or our pastimes when in the line was to launch rifle grenades aimed to enfilade a German trench. These consisted of a bomb attached to a metal rod which was inserted in a rifle held in a fixed position and projected by a blank cartridge. The rifle grenades were designed to explode on impact. As they occasionally exploded when the rifle was fired it was wise to take shelter behind a sand bag wall and to pull the trigger by remote control. I believe that the aiming was too inaccurate to cause many enemy casualties.

The same philosophy that dictated that for the sake of his character the allied fighting man must endure the maximum of danger and discomfort in makeshift trenches must have influenced the Army’s culinary arrangements.

Napoleon’s well-known dictum that an army marches on its stomach was ignored or misunderstood. The bomber platoon which I joined on arriving in France had its own cook who was chosen not for his skill or experience but because he had volunteered for the job. Apart from the prerequisite of obtaining a larger share of the rations than the rest of the platoon the inducement which attracted the candidate was exemption from parades and working parties. But as against this privilege the cook had to carry on his task of boiling water for tea, making stew and frying bacon with damp green wood in wretched, cramped quarters where the smoke was suffocating. To look at our cook with his greasy, dirty uniform, his red-rimmed eyes and smoke begrimed face, it was hard to believe that his dreadful ordeal was a matter of free choice and not imposed as a brutal punishment. The sad part of the story is that the quality of our rations was good and could have produced palatable meals. Later on it occurred to someone in authority that since the troops returned time after time to the same billet it would be expedient to install proper stoves and to train cooks to make better use of the rations. The result was amazing.

After a few days reorganizing the battalion was ready for action. I volunteered to become a member of the battalion bombers. Their function was to attack along a trench by throwing bombs into a section or bay of a trench and to follow up the explosion with the bayonet.

Each section consisted of seven or eight men: half bomb throwers and half bayonet men. We had the mills bomb which was a deadly weapon as it burst into many small pieces of shrapnel whereas the German bomb, the potato masher as it was called from its shape, had a lot of explosive but very little shrapnel.

We first moved to a support position at what was known as the White Chateau where my group were assigned to a trench about 200 yards in front of a battery of heavy guns.

Between our trench and the battery were dugouts occupied by other members of the battalion. The first afternoon the Germans shelled the battery with high explosive shells and large calibre shrapnel which exploded with a noise like the crack of doom and a large cloud of black smoke which the troops referred to as wooly bears.

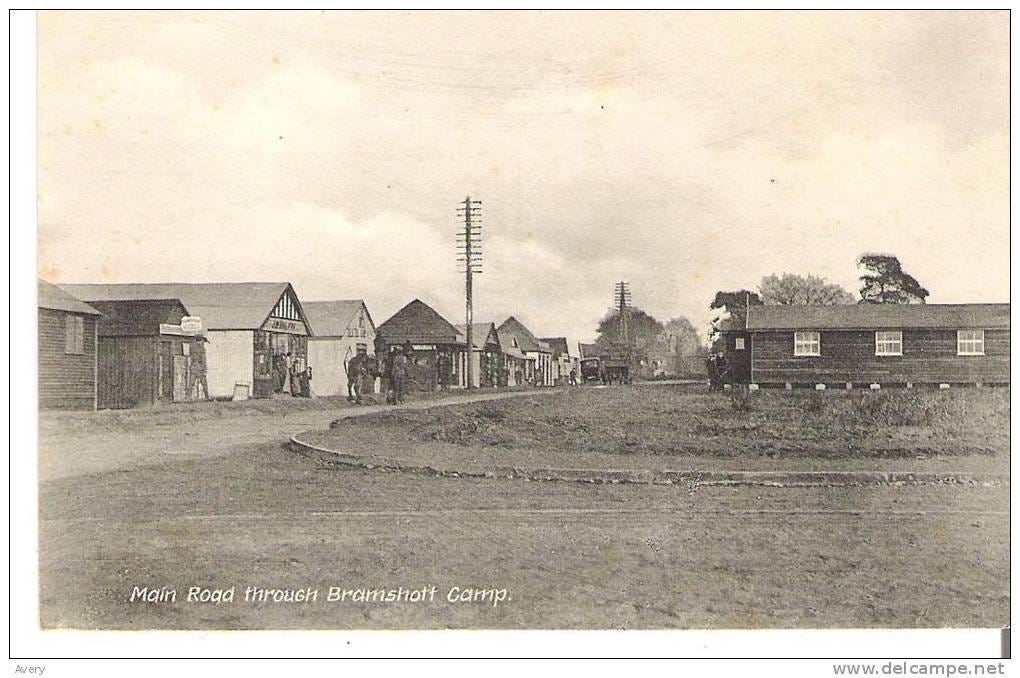

As these shells exploded directly above our heads they could not harm us but the sound was so terrifying that I began to doubt if I could stand it. From the White Chateau, we moved to the front line at a point in the perimeter called Hill 60.

From: Incredible century-old panoramic images of First World War battlefields

At this section the trenches were only 75 to 100 yards apart and had many curves. One of the duties of the bombers was to joint the battalion scouts in reconnoitring between the lines to detect enemy working parties and to take a prisoner if the opportunity offered. It fell to my lot on the second night to accompany a cost on such a mission. As no-man’s land was a sea of mud I was dressed in a rubber suit, and armed with a revolver and two hand grenades. I followed my companion over the parapet and through our wire entanglements and out into an uncharted desolation. I had no idea what to look for but I suppose I did serve as moral support. After about two hours of wandering in the mud the scout started to climb through the wire to get back into our trench but he suddenly decided that he was climbing through the German wire due to a curve in the front line. We lost no time in leaving and the scout was very careful to get his bearings before our next attempt to regain our trench.

Our second trip to the front line was to a section to the right of Hill 60. My companions and I had just reached the support trench when the Germans detonated a land mine under our front line. The explosion was tremendous and I am sure the ground on which I was standing heaved up about two feet. I expected a German attack but it did not come and the only result was the death of those who were in the front line at the time and the creation of a large crater. Our tour of duty in the salient lasted a few more weeks but were uneventful. We had a number of casualties, some by being shot through the head by German snipers.

When we left the salient we marched south to engage in the battle of the Somme, which had just started. Marching about 20 kilometers a day was no picnic as each man carried about 90 pounds including his rifle and ammunition. It was at this time that General Currie, an amateur soldier from Vancouver, became commander of the Canadian Corps. He was never popular but with the assistance of a number of able British officers on his staff I believe he did an excellent job. It was important for our morale that the corps fight as a unit, and by insisting on this and on adequate planning and preparation for attacks he built up our reputation as shock troops and raised our pride and esprit de corps. A change which helped our morale was the introduction of spit and polish in place of the slackness in dress and demeanor which had hitherto prevailed. This meant brushing the mud off our uniforms polishing the brass on our equipment and coloring our webb equipment. It also meant smartness on parade and the properly executed ceremony of the changing of the guard.

Desertion in the face of the enemy had traditionally been a capital offence and perhaps in conscript armies which rely on blind obedience it serves a useful purpose, but in a citizen army where discipline is largely a matter of pride and self-respect I believe it does definite harm. This was brought home to me when one unfortunate young man who had left the trenches in the Ypres salient and tried to hide out as a French civilian was caught, courtmartialled and shot by a firing squad in front of the whole battalion. I was away on a bombing course at the time and learned of it on my return, but I know that this drastic action was detrimental to the morale of the 3rd Battalion. By the outbreak of the Second World War the Canadian medical authorities had realized that some men cannot stand the constant strain of facing danger so they tried to detect this lack of stability and probably saved many breakdowns by keeping such individuals from serving in the front line. In my opinion, courage is a matter of will power, and this uses up nervous energy which if the ordeal lasts long enough will be exhausted. I recall one of the survivors of the June battle in the salient who broke down completely when the Germans opened a barrage on our trench and had frequent fits of crying, but his friends helped him to regain his self-control and he later became a very fine sergeant.

One of the horrors of war about which you read nothing in wartime reminiscences is lice. Within a few days after arriving in France and throughout my entire service in the ranks in France I was constantly lousy and I hated every minute of it. The army arranged for bath parades and issued clean shirts and underwear but they were infested with lice eggs which hatched on the march back to camp and the straw in the barns where we were usually billetted were literally crawling so it was impossible to get rid of them. It is difficult to classify as civilized a nation where lice would be tolerated. It is necessary to go back a long way in Canada to find hotel bedrooms infested with bed bugs and only recent immigrants from Europe were lousy.

Logically war is merely a weapon in the game of international politics in which the aim is to strengthen one’s country and improve the lot of one’s people. But for about one hundred years the policy of Germany was controlled by the military caste who looked on war as an end in itself, and winning battles the goal to which all national effort must contribute. It was not surprising , therefore, that Germany produced excellent soldiers and competent generals who excelled us in the practical aspects of fighting.

Our general staff appeared to be obsessed with the idea that safe dugouts destroyed soldiers’ aggressive spirit and that discomfort was beneficial, like the cold morning tub and unheated houses. The Germans always chose high ground for their trenches and within hours of taking up a defensive position dug a deep trench and started digging stairways and galleries at least 20 feet below ground which were completely protected from artillery shells. The Germans appeared to have a good supply of pit props which fitted together to form a strong wooden lining to their stairways and galleries. These dugouts must have saved many casualties and have provided rest and comfort, which sustained the morale of their fighting men.

The 3rd Battalion gained no laurels in the battle of the Somme. We made three trips to hold the line for varying periods between attacks by other units, and a final and disastrous trip to engage in an unsuccessful attack to take Regina trench. History has recorded the dreadful slaughter of our soldiers in this summer-long engagement, which gained us a few miles of ground but which contributed nothing to ultimate victory. The bomber platoon to which I belonged consisted of about 35 to 40 men and one officer and we were attached to battalion headquarters. When the battalion took over the front line at the pile of bricks which had been the village of Pozieres there was some misunderstanding as to where we were to be stationed, so we spent several hours going up one trench and down another under a steady rain of shrapnel.

To make matters more difficult, the trenches were narrow and were made almost impassable by a web of signal wires along each side. The explanation of this was that when one signal wire was broken by shell fire another was strung up to re-establish communication. As it was impossible to carry a stretcher along such a trench, the wounded were carried overland showing a red cross and the Germans usually refrained from firing. However, when I was a member of such a stretcher party, the Germans opened fire on us with a field battery and we had to take cover in a hurry.The man at the front of the stretcher I was carrying was hit in the back of the head by a small piece of shrapnel and I helped him to the dressing station, but he died a few hours later. One of our jobs as troops holding the line was to dig jumping-off trenches for the unit selected for the next attack and I recall one grim occasion when we were digging such a trench on a bright moonlit night and German snipers were taking a steady toll. No troops ever dug more vigorously to get below the line of fire.

Canadian soldiers going over the top at Pozieres.

My recollection of the tour of duty at Pozieres was the constant and accurate shell fire of the Germans who appeared to know within an inch where the trenches were located. Narrow escapes were commonplace but I remember two. Once when the parapet of the trench was blown in on me but as there was a dead body in the side of the trench I was not buried. The other was when I woke up and saw that a dud shell had entered the side of the trench opposite to me while I was asleep. If it had exploded I would still be sleeping.

Sugar Refinery at Courcelette: source

Our second tour was to the ruins of the village of Courcelette with the ruins of the local sugar refinery as a landmark and a sunken road which inevitably was enfiladed by German artillery. Between our trips to the front line we were marched back 20 kilometers a day for three days, and then marched back again carrying everything we owned on our sore shoulders. One day after the front line had moved well beyond Courcelette I took a walk to view the scene of war and was surprised to find that the bodies of the scores of dead Canadians and Germans which were lying still unburied where they had fallen had become mere skeletons. During our third tour I had an opportunity to put my skill as a bomb thrower into practice.

Two of us were at a block in a communication trench which led to the German lines when a potato masher bomb landed between I believe that my companion moved to throw it out but it exploded and blinded him. I never heard how seriously he was injured. I received several small bits of shrapnel in the face. I immediately went into action and and threw mills bombs into the trench ahead of us from where the German bomb had come. The fuse of a mills bomb is designed to reach the detonator 5 seconds after the bomb is thrown, so the art of throwing is to lob it high in the air so it will explode just after it lands. It was twilight so I could see German soldiers going overland to reach the communication trench so it looked like a serious attempt to force us back. I believe that what saved us was that several large high explosive shells intended no doubt for us fell short in the trench where the Germans were assembled. At all events we held the block without any more casualties.

Photo: Aerial photo of Regina and Kenora Trenches at the Somme

Our final effort in the battle of the Somme was a brigade attack to capture what was called Regina trench. I believe several unsuccessful attempts had been made to take this trench by battalions of the 4th Canadian Division. My impression is that our attack was hastily organized and not well-planned. It was quite a long distance from our jumping-off point to our objective and we had to advance over a rise and then a long descending slope and were therefore exposed over a long distance to machine gun fire and shrapnel. The battalion bombers had 36 men and were to advance in the third wave on the left of the attack among men of the third brigade. Our jumping-off point was in no-man’s land and we waited for zero hour in large shell holes which we enlarged to give us some protection from machine gun fire and shrapnel. Generally speaking, the young lads in our platoon were very reserved but the proximity of death in the Somme must have had some effect for when I visited one group in a nearby shell hole I found them saying their prayers as if they had a premonition of impending disaster.

And a disaster it proved to be. The battalion entered this battle about 900 strong and we numbered just over 100 when we reached our billets late that night.

When our artillery barrage opened at zero hour the hail of bullets and shrapnel facing us was terrific. It was like facing a blizzard with the constant buzz of machine gun bullets and the crack of those passing close to one’s head and the explosions of shrapnel shells adding to the clamour. I trudged steadily forward and had gone several hundred yards when I realized that I was all alone. It occurred to me that I could not win the war by myself, so while I considered the situation I took shelter in a shallow trench, where I found a wounded Canadian belonging to the third brigade. He was too badly wounded to walk so during the day I went back several miles and obtained a stretcher and when darkness permitted stretcher bearers to come forward I saw that he was carried out.

The short trench in which I spent most of the day was evidently one of a number of short trenches dug by the Germans, to be joined together later to form a communication trench but which in the meantime formed a

shelter from shell fire.

I was told later that on the left of our attack the barbed wire had not been destroyed by the artillery, so those of the 3rd brigade who survived the machine gun bullets were unable to reach the German front line. On the right our men did reach and capture the German front line, and held it for most of the day, but ran out of bombs and ammunition and had to retire. Apparently it was impossible for reinforcements and supplies to be brought up over the open country in daylight. One of my companions in the bombers had been assigned for this attack to carry messages from battalion headquarters to forward positions and he told me of his experiences. He was a tough Italian from Montreal, Tony Badalli, and, as he told it in his broken English, he had a most exciting day. How he came through was a miracle, and I believe that he was the only one who did. Every time he returned to battalion headquarters the signal sergeant gave him another tot of rum so he was hardly conscious of the bullets.

Once more the battalion had to be reinforced and reorganized and made ready for its next task, which was to hold the line on the Vimy Ridge front. In line with new ideas on strategy the battalion bombers were abolished and I was placed in Number 14 platoon of D Company. When we entered the line again we were at full strength, but to illustrate the difference between shock troops and the ordinary British battalion, we relived a unit with about 250 men who had kept the front as quiet as possible, no doubt with the collaboration of some third-rate unit of the German Army with the same pacific intentions. They were in for a rude awakening.

The orders from headquarters were to take the offensive and we proceeded to do so. We brought in large trench mortars which could penetrate their dugouts, and our artillery gave their trenches a daily pounding. The various units in the Division staged a number of raids on their trenches to take prisoners and to keep the German soldiers uneasy. I was not chosen for our raiding party. The Germans retaliated with minenwerfer, a large can filled with high explosive which would be dodged since it went high in the air. Our casualties were quite low. We made regular tours of duty, 6 days in the front line, 6 days in support and 6 days in reserve, with an occasional night working party to carry in stakes and wire for wiring, sandbags and other materials, to dig trenches and put up more wire entanglements. It became evident that we were preparing to attack Vimy Ridge which for many months had given the Germans the high ground overlooking our trenches.

As April 9th approached the drain on our transport to bring up ammunition for our guns affected our rations, so dry army biscuits and bully beef became acceptable fare. Faint with hunger I made the mistake of enjoying a feast of canned peaches and Devonshire cream at a Y .M .C .A . canteen. I had never had stomach sores in my mouth before, and when these developed while I was still at Farbus wood I assumed I had some virulent disease, packed my belongings and prepared to go to hospital. It was a decided let down to be given the army’s universal cure-all, a No. 9, a violent purgative, and sent back to duty.

In the attack on Vimy Ridge, the 4th Division was on the left of the Canadian Corps, next, the 3rd Division, then the 2nd , and my Division - the 1st - was on the right with the 51st. Highland Division on our right. The attack was preceded by a terrific shelling of the German trenches and batteries and the attacking troops followed a well-organized creeping barrage. The attack went very smoothly except on the extreme left where the 4th Division had difficulty gaining their objective.

The 3rd Battalion was in the third wave so we could watch the first two waves move forward in the face of machine gun fire but very few shells, probably because we had knocked their batteries. Our advance was made with few casualties and we reached our objective without any difficulty. Our casualties came later from German shellfire. My platoon reached Farbus wood which was the most advanced point of the attack and we were able to look down on the flat expanse of the Douai plain. Shortly after our arrival a small troop of the Canadian Dragoons rode forward but they were wiped out in minutes. Men and horses lay scattered over a small clearing beside the wood. All the cavalrymen were dead except one whom we carried to the dressing station. Not long after this we had a visit from Canon Scott, the senior Protestant chaplain of the 1st Division. He spoke to us in his usual breezy style and invented a British naval victory to cheer us up. He looked on the war as a Christian crusade, and not only exhorted the men but set an example of courage by exposing himself to the same danger as they had to face. Eventually he was wounded and I met him again in hospital. He was awarded the D.S.O.

The result of our heavy pounding of the German lines was that a strip five or six miles wide was so churned up that it was impassable for guns or ammunition, so that it was impossible to follow up the capture of Vimy Ridge. When roads to the front were made passable our advance continued but our attacks were on a small scale and in this way we captured the villages of Arleux and Fresnoy.

The Canadian Corps moved to Vimy Ridge in October 1916 and remained there

for over a year. After the attack on Vimy Ridge the 1st Division occupied various sections of this front from Mount St. Eloi to Hill 70 and Lens but never engaged in any major battle involving heavy casualties. We came to accept soldiering as a permanent way of life, which, since the war seemed likely to last forever, could only end for the individual by being carried out on a stretcher or wrapped in a blanket and buried. In spite of such resigned and gloomy reflections our morale was high and we made the best of good billets and such recreations as were available. At this time I did some boxing, particularly with two very good men, one a middleweight named Lewis and the other a lightweight, both from Toronto. I was a welterweight although I was a tall then as I am now and I engaged in a bout with another welterweight in the battalion and I won. I was then asked if I would stay out of the line and train for an Army sports day with the two boxers I have mentioned, but I refused. I derived some satisfaction when the two 3rd battalion boxers won in their respective classes in this tournament.

The Canadians were on good terms with the French civilians but the language barrier limited their communications to the purchase of beer, red wine, cognac and fried eggs and potatoes . There were not many French people in the forward area where we rested between tours in the trenches and very few French girls. It was only occasionally that we billetted in a large town such as Brouai. I tried out my smattering of French whenever I could, but not enough to improve it.

Behind the lines in the Somme area I met a Frenchman who recounted to me his experience as a British spy in the first year of the war. His occupation before the war had been smuggling between France, Belgium and Holland and he had been caught and had served a term of imprisonment. When war broke out the French authorities asked him if he would act as a spy for the British and he agreed to do so. He was taken to England and given instructions on communicating the information he obtained by carrier pigeon and then dropped behind the German lines by parachute. A cage with several pigeons would be dropped at a stated time and place and he would specify where and when the next drop was to be made when reporting the information he had obtained. He had found it wise to keep in hiding and to rely on his pre-war contacts to gather information as to the strength and identity of German units and their movements. When things became too hot he crossed the Belgium border into Germany, then crossed into Holland and was then taken by boat to England. He showed me documents to verify his story.

I met the finest men I have ever known in the 3rd Battalion. An idea promulgated by pacifists is that good soldiers must be insensitive and brutal, but this is quite wrong. Self-control, intelligence and keen perception are the qualities which make men outstanding in war and in peace. From the Colonel down they were good soldiers and helpful comrades. Col. J. B. Rogers was a cheerful and imperturbable leader; the adjutant, Capt. W. H. Kippen, was a most conscientious and capable adjutant; Major Buster Reid, who was my company commander, was a deservedly popular officer. Tommy Moulds, our company sergeant-major, was very young for this position and in no way resembled the popular idea of a rough-talking martinet. He had great influence because of his thoughtfulness and qualities of leadership; without question, he was one of the finest men I have ever known. There were many others. He was given a commission in the field, but like too many good men he was killed.

We had a sergeant, Billy May, who wore the blue epaulets to show that he had come to France with the battalion in February 1915. I presume the authorities decided in the summer of 1917 that he had done enough so he was sent back to the reserve battalion in England , but he could not stand the peace-time soldiering and applied to return to France, and was killed. A corporal named McRae in our company later obtained a commission and he survived to serve in the 2nd World War as a major in the South Saskatchewan Regiment. He was in the attack at Dieppe and was awarded the D.S.O.

It seems to me that sharing danger brings out the best in men and my companions in the 3rd Battalion almost without exception were generous and helpful. As we had to carry everything we owned on our backs we naturally kept our possessions to a minimum. The practice until well on in the war was for parcels for men who had become casualties to be shared among the other men in the platoon, so there was never any shortage of new socks or sweaters. It was therefore a great shock when in the later stages of the war men began to have small items stolen. The explanation was that the Canadian Government, to meet the need for reinforcements, started to release men from jail who would volunteer for service at the front. Such men were not identified in any way but when they reached the battalion they would not resist the impulse to steal, even when the theft served no useful purpose. Only once did I see men engage in a fight. As we sat glumly waiting to be marched back to our billets after the disastrous attempt to capture Regina trench in the Somme, two young fellows climbed out of the trench and started to strike each other with their fists. The absurdity of quarrel in the face of such terrible slaughter was too much for the bystanders and they laughed the two men out of their anger.

Up to this point I have never mentioned aeroplanes because while they had made an appearance in the sky above the battlefield in the Somme, our concern was with our mundane affairs, such things as machine guns, shells, trenches, lice, wire and mud and we were not aware that air supremacy could

affect the outcome of our battles. But on the Vimy Ridge front, air battles became more frequent and we often watched these thrilling combats. I recall seeing a group of Richthofen’s fighters with their decorated planes follow one of our artillery observation planes with the observer firing his machine gun until it crashed.

Richthofen’s fighters - Richthofen was known as “the Red Baron”

During the summer I was interviewed by a Brigadier General, whose name I have forgotten, to inquire if I would accept a commission. I said yes but as I heard no more about it I assumed that nothing would come of it. I had an opportunity at this time to have 10 days leave in Paris, but leave to me meant seeing my relatives and attending London theatres so I refused.

It came as a surprise to me when in November 1917 after 16 months in France I was told that I could go on leave to England. My recollection is hazy but I am sure that at the base in France I was given lice-free clothing since I know that I was free from them on leave. Since then being lousy is merely a revolting memory. When I returned to France as a lieutenant I had my own bedroll and my own underclothes which gave me complete immunity.

Before my 10 days had expired I received a wire addressed to me at my Uncle Will’ s place of business, which ordered me to report to the reserve unit at Witley camp instead of returning to France.

When I did so I learned to my surprise that I was to attend a school for officers at the seaside town of Bexhill in Sussex to commence on January 1, 1918. In the meantime I could have all leave I wanted; so I visited my relatives in Leek, Staffordshire, for a week and then spent a week at the home of my former sergeant, Jim Beaumont, who lived in a suburb of Birmingham. Jim at been commissioned in the field and in been wounded at Fresnoy and was in a hospital near his home. After the war he wrote me urging to visit him at his homestead at Golden in British Columbia, but I was then too busy learning to earn a livelihood to spare the time

The Officers Training School at Bexhill was under the command of Brigadier-General Critchley who had been a lieutenant in the Lord Strathcona’s Horse stationed at Fort Osborne in Winnipeg when I had been a member of the cadets of the regiment. The course was quite rigorous: up at 6:00 a.m ., p.t. for an hour, then studying map reading and infantry tactics during the day and frequent route marches. I did quite a bit of boxing during the course and took part in a boxing tournament. I had as one opponent, a sergeant who was a boxing instructor permanently attached to the school. We went three rounds and the judges required another round to decide the winner. They gave the nod to my opponent but I felt this was no disgrace.

The men attending the course were from all units and were a varied lot. I recall an escapade of four of those in my billet. They had gone by bus to Eastbourne and had stayed at a party till long after the busses had stopped running and were in danger of missing the morning parade at 6:30 a.m., which would have meant dismissal from the course. In that terrible predicament they showed the initiative to be expected of representatives of the Canadian Corps by commandeering a milk wagon but since the driver was absent at the moment, without his knowledge or consent.

The first officers with the Canadian forces were men who had trained as officers in the militia, and then for a time commissions were given on the strength of political influence or personal friendship. But battle experience showed that the best source remained in the ranks with displayed qualities of leadership, by the end of the war most officers with Canadian infantry units had been promoted from the ranks. Some who had been senior n.c.o.’s were commissioned in the field and others like myself, who is only a lance corporal, we’re given a course of training and commission after proving their confidence. Such man who demonstrated their steadiness under fire and were familiar with the situation.

Discipline was never a problem in the 3rd Battalion or with any of the fighting units. Riots did occur at reserve units due to slack administration and boredom, but in France discipline was taken for granted. To some extent it was due to the fact that as individuals we felt that it was our war. It was not due to having good officers as they were not all good , and in the trenches the men rarely saw their officer, and yet duties were performed conscientiously. One element, no doubt, was that after a time the battalion became like a large family and acquired a definite esprit-de-corps . I also believe that as a people, perhaps due to our cold climate, Canadians have a natural respect for authority.

From Bexhill I was sent as a lieutenant to the reserve unit at Witley camp in Surrey. The duties while waiting to return to France were light, and another lieutenant, named Hills, and I spent our free time cycling in the countryside and visiting Guildford, where we made friends with the two daughters of a local solicitor and often went canoeing with them on the river Wye. But this pleasant life did not last long and I was soon back in France. We have an awful experience of having our train bombed by a German plane but several near misses did no harm. When I was stationed at Sanderling Camp in 1915 German planes dropped bombs on nearby billet and killed some Canadian soldiers and many civilians were killed in a raid on the town of Folkstone. Early in the war zeppelins dropped bombs on Monday but these were isolated incidents which had no significance in the war.

I reported to a reserve unit near Arras and was attached to various working parties digging trenches in the Arras area. On March 21st, 1918, the Germans commenced a large scale well-prepared offensive in the Somme front and made a very large advance, causing large casualties to the 5th British Army. Further German attacks were expected, and to meet this possibility many trenches were dug in the rear areas. But the Germans struck next in the Ypres salient and again made great gains. To the soldiers the situation looked very ominous and I listened to Canon Scott, whom I mentioned before, make an impassioned speech exhorting the men at the reserve battalion to give no more ground , but to stand and die if need be. These great offensives were the last desperate try for victory by the German General Staff, who knew of the inexhaustible flow of men and munitions from the United States, which were certain to overwhelm them unless they could deal the Allies a mortal blow. These attempts, while apparent victories, failed of their purpose and were merely a prelude to the tremendous counter-attacks by the British, French and American forces. On August 8th, 1918, the Canadians along with French and Australians attacked at Amiens, and on that day advanced 10 miles and continued to advance until on August 11th, when they were relieved and moved north to the Arras front. Here the 2nd and 3rd Divisions had already made a splendid advance. I joined the 3rd Battalion while it was still engaged at Amiens and was placed in command of the No. 11 platoon in B. company, commanded by Major Crawford.

The first Brigade of the 1st Division was ordered to take a position held by the Germans along the Arras-Cambrai road in preparation for an attack on the Hindenburg line. In the early hours of the next morning B Company was led into no man’s-land by a guide to take it to its appointed place to start the attack, but as sometimes happened he lost his way and while he studied his position the line of 4 platoons halted and the men lay down. The other three platoon commanders went forward to speak to Major Crawford at the head of the line, but I stayed with my platoon. After a very long wait I went forward to investigate the protracted delay and discovered that the major, the three platoon commanders and the guide had moved off with No. 9 platoon leaving me and the three other platoons somewhere in no-man’s land. I was not responsible for the blunder but my duty was to get the three platoons to their jumping-off position in a hurry. It was quite dark and there were no landmarks but I set off walking in a wide circle and fortunately found a man of the 3rd Battalion and not a German outpost. I was able to take the three platoons to their appointed place in a sunken road two minutes before zero hour.

My recollection is that I had about 30 men in my platoon, which on the front of 100 yards we were to cover, makes a thin line. The plan of the attack was that our battalion was to attack the enemy position from the west and that the 1st and 2nd Battalions were to attack from the south. I was about the centre of my men and after going forward a considerable distance without casualties we came on a trench system and quite a number of Germans jumped up, some firing at us and others holding up their hands as if to surrender. I shot at a German on my left front, and as I did so another German ran forward and pointed his rifle at my chest. I shouted to distract him and raised my right arm to shoot him with my revolver, and as I did so he fired. Instead of hitting me in the chest his bullet hit my right upper arm and smashed into my shoulder joint and knocked me over. The haemorrhage from my lung choked me and I lost consciousness.

When I came to I saw the German soldiers coming from the west. I also noticed the dead German lying in the trench so the slug from my revolver may have hit him at the moment he fired his rifle at me. I did not want to be taken prisoner so I managed to get around the corner of another trench and met some of the battalion, including my batman. I had forgotten his name but I know he was an older man came from Toronto. I’m grateful to him for he found the stretcher and two German prisoners and had them carry me to the dressing station. For me the war was over; I was one of the lucky ones. The war ended for me with me on the stretcher not wrapped in a blanket.

I was soon in an ambulance and on the way to the Casualty Clearing Station which was a large field hospital. As I had bled from the lung I received a tag marked “lung case” and the appropriate treatment was to leave such cases quiet so as not to cause more bleeding. But when I had been left for about four days with no attention and began to get delirious I insisted on seeing a doctor who, immediately he felt my shoulder, had me in the operating room to open it and let out the pus. Practically every wound in the First World War became septic so my condition was not unusual. Due to the smashing of the joint the infection continued for many months until all the bits of dead bone had been removed. I believe I had eight operations first to improve the drainage then to remove the dead bone. In the nine months of my treatment I was in the base hospital at Boulogne, the first London General Hospital on Wandsworth common, a Canadian Officers Hospital of the Petrograd Hotel in London, the Canadian hospital at Buxton, and eventually in Deer Lodge Hospital in Winnipeg. Finally in June 1919, I took up my civilian life again.

Frank M. Bastin

***

There is more to the story - when he was wounded, his family was told that he was dead, and he revealed to them a number of weeks later that he was, in fact, alive.