The 1970s: An Intellectual Coup Against Democracy

It's time to update the economy's operating system, and replace the one installed in the 1970s.

From the 1930s to the 1970s, Keynesian economics were mainstream economics. It was generally accepted that capitalism had its faults, and that in order to relieve poverty you needed a social safety net. What’s more, governments and central banks could play a role in “smoothing out” the ups and downs of the economy. In an economic downturn, they governments could stimulate the economy to get it up and running again, and they could pay down debt in good times.

One of the decisive shifts away from Keynesian economics in the 1970s was because Keynesians had never anticipated the phenomenon of “stagflation” - prices going up while wages went nowhere - but Milton Friedman had. It was a phenomenon that seemed to confirm the validity of Friedman’s theories while disproving Keynesian economics.

Under Keynesian economics, Central Banks and governments worked to “smooth out” the business cycle: deficit spending and economic stimulus in bad times, government restraint (and even tax increases) during good times to pay off the debt that has been accumulated.

In Friedman’s conception, inflation was caused by “too much money chasing too few goods.” The “Monetarist” answer to fighting inflation, as proposed by Friedman and others, was “greater labour mobility” (making it easier to hire and fire workers) lower taxes, and less regulation. It also meant that central banks pursue inflation-fighting policies as well, including either hiking or lowering interest rates to discourage or encourage borrowing as necessary.

In its more crude version, if there are problems in the economy, it is argued, it is not due to any failings on the part of the free market, which is efficient, but due to government intervention (or interference) messing things up.

In response to the economic crisis of 1970s, the world experienced an intellectual coup: the fundamental economic ideas that had been used to run the world’s richest economies were rejected, and replaced with something new.

While Keynes’ ideas were incredibly influential, they were never formalized mathematically. One of the key aspect of Keynes’ work was that he wanted to emphasize uncertainty, which is a challenge to express mathematically.

One formula did emerge, though it was not a part of Keynes’ work. There was thought to be a connection between inflation and employment. As economist Steve Keen writes, “This was called the "Phillips Curve", after the New Zealand engineer-turned-economist Bill Phillips, who wrote a famous empirical paper on inflation and unemployment called "The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957".

For many years, the connection was very strong – to the point that US economists could predict employment with amazing accuracy in the 1960s. That started to fall apart due to a number of different factors, both domestic and international. There was a global gold standard, which was one of the ways countries could ensure foreign exchange of currencies. The war in Viet Nam had incredible costs, and resulted in US money flowing overseas and creating issues with balance of trade. The U.S. went off the gold standard, which destabilized international currency markets.

Domestic debt was building. While many Americans were basically debt-free at the end of the second world war, the real estate and banking industries had lobbied to loosen regulations around lending, which meant that personal debt and housing prices were creeping up.

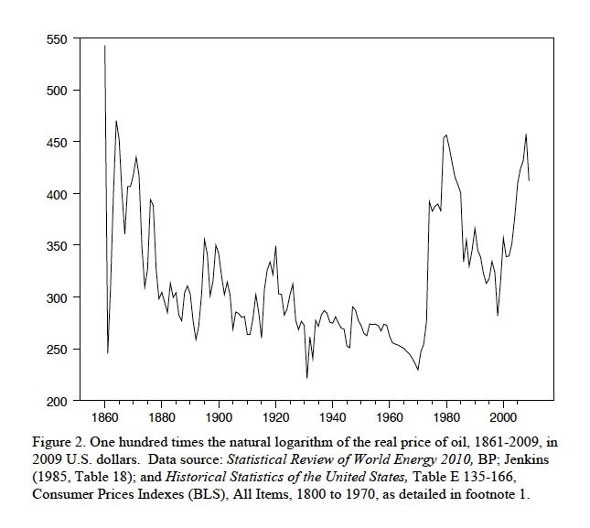

The other factor was a massive and unprecedented spike in the price of oil – as Keen writes:

“A second factor, which had never happened before, caused price rises well above the rate of wage growth: rising oil prices. Before 1973, oil prices were largely set by Big Oil: the western-owned oil companies that dominated oil drilling around the world, including in Arabian countries. They paid the oil producing countries a pittance in royalties, and prices were low and stable … the price is a flat line between 1950 and 1973. The resentment at being paid low prices for their vital commodity motivated oil producing countries to form OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) in 1960.

After the defeat of the Arab armies in the Yom Kippur War, OPEC launched an embargo on oil exports to the USA, which caused the oil price to increase by 250%, from $4.30 to $10 a barrel, in just one month.”

Production in industrial economies depends on the combination of labour, capital machinery and energy to do productive work. In a 2013 paper, economist James D. Hamilton found that every U.S. recession for over a century was preceded by an oil shock, and that the shock was more than just the extra pinch to drivers at the pump. The effects of the shock were far greater than just ‘crowding out’ other purchases - an order of magnitude greater, meaning that, for example a $300-million overall increase in oil prices would have a $3-billion negative impact on the economy. In an industrialized economy, energy plays a role beyond that of a mere commodity: it underpins every aspect of the economy – work, heat, light, fertilizer, production and transportation.

This is a chart that amplifies the price of oil to make it more obvious. Recessions happen just after oil prices go up, periods of growth happen when the cost of oil goes down. (I say recessions as separate from financial crises like the crashes of 1929 and 2008.) As Hamilton writes, the “Key post-World-War-II oil shocks reviewed include the Suez Crisis of 1956-57, the OPEC oil embargo of 1973-1974, the Iranian revolution of 1978-1979, the Iran-Iraq War initiated in 1980, the first Persian Gulf War in 1990-91, and the oil price spike of 2007-2008.”

Hamilton details how shortages had a widespread economic impact far beyond simply having to spend more on oil. He cites an article in the New York Times that illustrates the impact of the Suez Canal crisis on Europe: it put access to two-thirds of Europe’s oil supply at risk:

“Dwindling gasoline supplies brought sharp cuts in motoring, reductions in work weeks and the threat of layoffs in automobile factories... There was no heat in some buildings; radiators were only tepid in others. Hotels closed off blocks of rooms to save fuel oil. . . . [T]he Netherlands, Switzerland, and Belgium have banned [Sunday driving]. Britain, Denmark, and France have imposed rationing... Nearly all British automobile manufacturers have reduced production and put their employees on a 4-day instead of a 5-day workweek. . . . Volvo, a leading Swedish car manufacturer, has cut production 30%.”

The US was importing much more oil than it produced. That means US dollars money was flowing out of the country, massively enriching the members of OPEC. Oil is denominated in American dollars. This had distorting effects on the currencies of other countries – including industrialized countries that had a manufacturing sector for export.

When the price of oil soars, and people are buying from other countries it, even though a barrel of oil is priced in American dollars, the workers and companies in each country selling the oil are paid in their own currency.

So, if you are buying from another country, you have to buy their currency to pay for it. The more people are buying that currency at higher prices, the “stronger” it becomes compared to other currencies.

This new buying power is a double-edged sword. Because the currency as a whole had changed in value, the purchasing power for the entire country had increased. It’s now easier to buy imports from other countries, but it’s harder for those countries to buy your exports. The competition from lower cost imports hurts domestic manufacturers – and so do higher energy prices.

This was known in the 1970s as “the Dutch Disease” – because the Netherland’s manufacturing industries faltered when oil exports affected the value of their currency.

This was the economic backdrop that was used to argue that Keynesianism had failed. So called “stagflation” – stagnant employment and inflation – hadn’t been predicted by Phillips, but it had been predicted by Milton Friedman and his economic theory of monetarism.

Ha-Joon Chang writes:

"Inflation is thought of as a cruel, and maybe the cruellest tax because it hits in a many-sectored way, in an unplanned way, and it hits the people on a fixed income the hardest.” But that is only half the story. Lower inflation may mean that what the workers have already earned is better protected, but the policies that are needed to generate this outcome may reduce what they can earn in the future. Why is this? The tight monetary and fiscal policies that are needed to lower inflation, especially to a very low level, are likely also to reduce the level of economic activity, which, in turn, will lower demand for labour and thus increase unemployment and reduce wages. So a tough control on inflation is a two-edged sword for workers - it protects their existing incomes better, but it reduces their future incomes. It is only the pensioners and others (including, significantly, the financial industry) whose income derive from financial assets with fixed returns for whom lower inflation is a pure blessing. Since they are outside the labour market, tough macroeconomic policies that lower inflation cannot adversely affect their future employment opportunities and wages while the incomes they have are better protected."

It's important to understand that the changes that happened in the 1970s affected every level of the economy and continually redefined the role of government and business, in every way seeking not just to shrink the size of government, but to undermine democracy by limiting the capacity of government policies to effect change in every way imaginable – especially the Federal government.

Friedman’s ideas set out to dismantle the New Deal, but his specific recommendations to fight inflation were focused on union busting, lower wages and undermining the capacity of government to play a role in regulating the economy.

Central Banks –- were to be strictly independent from democratically elected governments, publicly owned, and according to Friedman entirely responsible for the money supply. Instead of acting for the public good, they act largely for the financial industry. Not all industry – just the financial industry.

“Greater labour mobility” is a euphemism for union busting and making it easier to fire people or hire them on a contract basis on the employers’ terms: with fewer or no benefits, and frozen wages.

Whether by accident or intent, all of Friedman’s anti-inflation prescriptions - greater labour mobility, less regulation, inflation-fighting central bank policies - have the effect of making it harder to earn money from work and easier to earn money from owning – especially from owning real estate.

Whether by accident or intent, all of Friedman’s anti-inflation prescriptions - greater labour mobility, less regulation, inflation-fighting central bank policies - have the effect of making it harder to earn money from work and easier to earn money from owning – especially from owning real estate.

Economic Historian Edward Chancellor has recognized these of these massive distortions to the economy. In an interview, about his book The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest, he says “After years of ultra-low interest rates, central banks created a bubble in pretty much every asset class, they facilitated a misallocation of capital of epic proportions, they allowed an over-financialization of the economy and a rise in indebtedness.”

The interviewer asks:

For years, central banks have shown an almost religious zeal to reach an inflation target of 2%. Where does that target come from?

That’s a bit of a mystery. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand was the first central bank to adopt a specific inflation target in the early 1990s, and then I think it really was a case of monkey see, monkey do. One central bank followed the other. The late Paul Volcker has actually said that there were no grounds for a 2% target. Of course, the idea was to give a little buffer against the horror of deflation. But if you don’t buy the deflation horror, then it does not in itself make sense to aim for 2% inflation. It’s generally a bad idea to set narrow targets, because people then don’t consider what’s outside the target. A broad literature shows that whenever someone pursues a target, all sorts of unintended consequences happen, because people game targets. Volcker didn’t believe in it. William White, the former chief economist of the BIS, wrote a paper in 2006, titled «Is Price Stability Enough?». His colleague, Claudio Borio, developed the financial cycle model, where he championed the idea that central banks need to incorporate other things, like the debt cycle, real estate prices, and asset prices.”

Chancellor adds that “It will turn out to be largely impossible to normalize interest rates without collapsing the economy.”

Friedman’s ideas resulted in limits on government influence on monetary policy, fiscal policy, tax policy, and economic regulations. Had his ideas only been confined to those two measures, the impact would be colossal – but he had another idea that helped change how corporations were run – something called “shareholder value.”

In 1970, Friedman wrote a blistering piece in the New York Times arguing that the only role of a CEO was to generate profit for the “real bosses” - the owners, or shareholders, and it was followed up in 1976 with a paper by two economists, Michael Jensen and Dean William Meckling, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership.” GE CEO Jack Welch used shareholder value for a while, then called it “The Dumbest Idea in the World.”

These are the basic economic ideas that have defined how most countries and the global economy have run for the last 45 years. For all the conspiracy theories about what governments are plotting, the defining characteristic of this brand of international financial capitalism is that they are actually the ones running the show – not government.

The Turning Point: 1978

For many countries, 1978 marked an economic turning point, because for many developed countries, it marked the year where the incomes of up to 20 per cent of the population stalled.

Whether it is a coincidence or not, that is the year that many countries adopted many of Friedman’s anti-inflation policies. While the credit or blame for these policies usually is attributed to the Reagan Republican revolution in the US, the Thatcher Conservative era in the UK, and the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney in Canada, the actual policy changes were earlier.

In the US, UK and Canada, parties of the centre left – the Carter Democrats in the US, the Heath Labour Party in the UK, and Trudeau Liberals in Canada, all adopted right wing anti-inflation policies based on “monetarism” all of which proved to be a failure when it came to policy, and drove their unpopularity and defeat.

Conservatives blamed centre-left parties’ economic policies for the failure, ironically since the reason they were failing is that they were the same “neoliberal” quasi-libertarian economic policies the conservatives wanted to bring in.

It is confusing because it is possible , in the right context, for the terms “classical liberal,” “liberal,” “neoliberal” and “fiscal conservative” to be used interchangeably. The so-called “neoliberal” or ““neoclassical” macroeconomic theories were, modern version of classical, liberal economics from the 19th century.

The confusion stretches back to the 1930s, because when Franklin D. Roosevelt – a classical liberal - started introducing “New Deal” policies to stimulate the economy, he effectively redefined what “liberal” meant. People who disagreed with Roosevelt and wanted to stick with the old system rebranded themselves as “fiscal conservatives.” They believed in limited government interference in the economy, low taxes, and balanced budgets.

In the 1970s, these fiscal conservatives rebranded themselves as “neoliberals” and “neoclassical” economics because they were bringing back ideas from the 1800s. It’s worth pointing out that in the 1800s, that many economies, especially in Europe, were feudal aristocracies. The people in charge had inherited thrones or estates or property and didn’t have to work for a living. Those who were working or harming often had to pay rent or taxes to these hereditary aristocratic landowners.

If we were to return to those ideas, the result would start to create a society where a tiny number of people owned almost all the property, and that everyone else has to rent because the property is too expensive to buy.

Friedman was not alone. Several conservative theorists and activists set out to undermine the left, but also to undermine democracy, or to create constitutional, legal, and political obstacles that would permanently undermine the capacity of a centre-left or left-leaning government to even implement policy, much less achieve results. In Chile, American conservative economists helped write a constitution that would make government action impossible.

Other examples include trying to formalize partisan fiscal conservative economic policies into law – through balanced budget laws, for example.

Politics drifted continually rightward in fits and starts in the 1980s and 1990s, but the effect of greater inequality meant that political parties of the right were creating a new generation of donors (including billionaires, plutocrats, and oligarchs), while impoverishing their opponents. The policies might hurt people, but they continued to deliver electoral wins for parties of the right.

The response of most parties of the “left” is that rather than seeking to push back, they tended to lean into the policies of the right. Actual parties of the centre were either crushed out of existence, or pulled apart, leaving two parties of left and right.

Just what it means to be “centrist” or “moderate” is challenged when one side – the right – keeps getting more and more extreme.

Canada’s federal government has multiple major parties. The rough public perception of the Liberals is that they are centrists, the NDP are left, and the Conservatives are right.

However, the Conservatives are far to the right of where they once were 30 or 50 years ago, and the NDP tends not to campaigning or governing from the left when it comes to fiscal matters. They are all fiscal conservatives.

The UK is dominated by two parties – Labour and Conservatives, as is the US with Democrats and Republicans. In many Canadian provinces, something similar has happened.

However, if both parties of left and right abandon the poor or the marginalized, they have nowhere to go, because all parties are operating from the same conservative “trickle down” economic ideas left over from the 19th century. That is what fiscal conservatism is.

It is not the same thing as being fiscally responsible, because the ideology of fiscal conservatism, across government and society, does not lead to balanced budgets and shared prosperity. It leads to social crisis, economic volatility, growth at the top and stagnation for the rest.

Greens, New Democrats, Labour, Conservatives, Liberals, Social Democrats, Socialists are all more or less trapped with this economic framework. It is the same trickle-down economics, which take as their premise that the surplus has to go to the top, where it will be reinvested in new businesses, new innovation and in creating jobs.

This apparently simple model is not how new business or jobs are created, but it does enrich people who already own property, and funnels more money to them to either buy more, or increase the price of the assets they own.

Vast amounts of research, innovation and discoveries in technology, agriculture and medicine are achieved at public expense. For the system to keep turning over requires that money goes back down to the people paying for the party – the borrowers.

The result of trickle-down economics and neoliberal ideas is a growing class of people who have been abandoned, driven out, or have given up hope on voting or democracy, because their vote may well elect someone, but not anyone who will change their life.

The option is not between left and right, it is between two economically conservative parties, one openly aligned with business, and the other openly aligned with labour. Neither party is seriously interested in taking a risk on policies they fear will make them vulnerable to attack, and possibly losing an election.

This is the common thread – and the common frustration facing so many people who want change – centrists and leftists alike – and cannot see why politicians can’t get action.

They are all following the same economic and political ideology that has set out to put democracy in chains, no matter what political party is in power.

Even where democratically elected governments have the support of their own citizens, and the measures they may take are peaceful, lawful measures (like debt restructuring), there is an effective political taboo based on a political ideology that seeks to ensure that the private interests of a few reign supreme.

We are not working for “growth” and we are not working for change, because we are too busy working to pay off ever-growing debt – numbers on a spreadsheet that will grow exponentially and inexorably of their own mathematical will.

We need to restore democracy - liberal democracy, with the rule of law, and with the critical balance between public and private, with effective enforcement of justice. We have to continue to place the value and dignity of individual rights over the collective. That includes limits on the collective power of government, corporations, unions, faith or any other collective to impose on the freedom of the individual - but also ensuring that we have an independent and effective justice system to hold people to account.

We don’t have that. It will take a lot of work to get to it, But the next intellectual revolution for the economy needs a humane, progressive, practical, centrist vision for the future.

Prof Steve Keen is launching a set of online lectures that are well worth the modest subscription fee. These are pitched at students and lay public seeking a better explanation for the failures of neoclassical economics and economists.