The Great Deception, Chapter 3: Strangers Within Our Gates

The Ferriers, the Woodsworths, Residential Schools & Eugenics

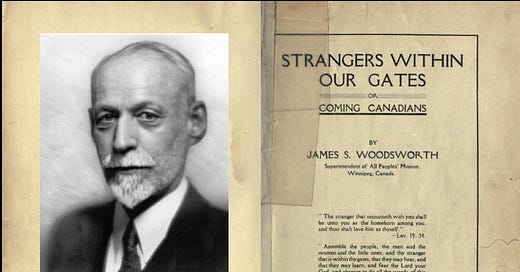

In 1909, J. S. Woodsworth set out his ideas of who would make a suitable immigrant to Canada in his book, Strangers Within Our Gates. He used it to rank the suitability of various nationalities to integrate into Canadian society, based on their race. Like the Reverend Thompson Ferrier’s book, it was a publication of the Methodist Church – specifically, The Missionary Society of the Methodist Church, Canada, the Young People’s Forward Movement Department.

It is not an overstatement to say that it was racist even by the standards of the age, with Indigenous people and Blacks being placed at the bottom of the list.

Having quoted Ferrier’s horrific stereotypes about First Nations, J. S. Woodsworth goes on to say:

“Mr. Ferrier thinks that the main hope lies in giving the young generation a good, practical training in specially organized industrial schools…

Much missionary work, evangelistic, educational, industrial and medical, has been done among the Indians.

Many are devout Christians living exemplary lives, but there are still 10,202 Indians in our Dominion, as grossly pagan as were their ancestors, or still more wretched, half civilized, only to be debauched. Surely the Indians have a great claim upon Canadian Christians!”

Woodsworth also quotes an American writer, John R. Commons – a social gospeller, prohibitionist and labor advocate, and pioneer in economics and Christian sociology. The way Commons describes blacks American is blatantly racist, and historically inaccurate to boot. Commons wrote:

“The very qualities of intelligence and manliness which are essential for citizenship in a democracy were systematically expunged from the negro race through two hundred years of slavery. And then, by the cataclysm of a war of emancipation, in which it took no part, this race, after many thousand years of savagery and two centuries of slavery, was suddenly let loose into the liberty of citizenship and the electoral suffrage. The world never before had seen such a triumph of dogmatism and partisanship.”

There is no question that blacks fought for their own freedom in the American Civil War, and there were some incredibly successful black American entrepreneurs, businesspeople, writers and politicians. There were people in the U.S. and elsewhere at the time who believed that blacks should have the right to vote. Commons is showing sheer bigotry and ignorance.

J. S. Woodsworth’s reaction was to write:

“Whether we agree with the conclusion or not, we may be thankful that we have no “negro problem” in Canada.”

Richard Sanders details Woodsworth’s anti-immigrant screeds:

“Woodsworth’s hateful view of the so-called “Oriental Problem,” revealed his dogged fixation on religion as a filter for judging aliens. Woodsworth’s section on “Chinamen” relied on a 15-page excerpt from what he called “a splendid little book” by Rev. J.C. Speer, a missionary and Methodist Minister like himself…

Perhaps the most slandered immigrants in Woodsworth’s overtly racist book, Strangers Within Our Gates, were east Europeans. He saw them as so politically inferior that he urged the Canadian government to “reform” matters by removing their right to vote…

Just after the outbreak of WWI, Woodsworth addressed Winnipeg’s prestigious Canadian Club on “The Immigrant Invasion after the War: Are We Ready for it?” This was one of 16 lectures in 1914 that were attended, on average, by 430 of the city’s most powerful men. His talk came between speeches by Solicitor General Arthur Meighen on WWI, and Prime Minister Borden on “Canada and the Empire.” Other speakers that year included the top brass from Canada’s ultraconservative military, banking and press establishments. The fact that Woodsworth was warmly welcomed by this powerful circle, reveals his role as the Canadian elite’s favourite “socialist.”

After listing 24 non-English nationalities pouring into Canada’s gates, Woodsworth asked:

“Mix these peoples together, and what is the outcome? From the racial standpoint it is evident that we will no longer be British, probably no longer Anglo-Saxon. From the standpoint of eugenics it is not at all clear that the highest results are to be obtained through the indiscriminate mixing of all sorts and conditions.... From the religious standpoint, what will be the outcome? For...most of our foreign immigrants do not belong to the churches which are... dominant in Canada. From the political standpoint it is evident that there will be very great changes and very serious dangers.”

Now, some will try to minimize Woodsworth’s statements about eugenics, by arguing that other people shared the same opinions, or that we shouldn’t apply today’s morality to the past.

There were many people who did not believe in eugenics, and others whose views were not as extreme as Woodsworth’s. The fact that many people are wrong about something does not make it any more truthful or accurate. Woodsworth’s opinions weren’t based on facts, because there were living examples at the time that completely contradicted what he was writing, and the others whose work he was citing.

Woodsworth’s “authority” on Indigenous people and education, Thompson Ferrier, is a person he knows –the principal of a Residential School where children went hungry, were forced to do unpaid labour, and where many died. Ferrier knew about Bryce’s report and denied its seriousness. Complaints about food, clothing and poor conditions continued on Ferrier’s watch.

Desperate times do not call for desperate measures. It calls for people to be level-headed, able to check the mistakes in their own thinking, to be able to describe reality – or the sharpest picture of it we can get – in ways that are unflinching and that may be tough to accept. Because if we do that, we can do more than cope with crises – we can prevent them.

One of the reasons Bryce was right where so many others were wrong was that he relied on statistics where others like Woodsworth and Ferrier were relying on racist pseudoscience.

Bryce’s focus was on “environmental factors rather than racial or ethnic characteristics” – he recognized that people are influenced and shaped by their environment, and he is working with data rather than stereotypes – so he ended up breaking stereotypes with evidence.

“From the very first questionnaire he gave following his appointment as Chief Medical Officer, a survey which covered about three-quarters of the population, Dr. Bryce noticed two startling facts. First, contrary to popular opinion, Canada’s Aboriginals in fact exhibited comparatively low levels of nervous disorders and alcoholism. Second, while most physical disorders occurred at similar rates in the Canadian population at large, those whose occurrence depended on heavy amounts of unsanitary contact, such as diseases of the eye and tuberculosis, were much higher among First Nations.”

Bryce realized the obvious – that if First Nations children received better nutrition, better ventilation, it would save lives. He further argued the Federal Government should be running everything, not churches, to make it less likely children would fall through the cracks.

He realized that the reason First Nations children were dying in residential schools was not that they were born weaker or more vulnerable, but because of what the government was doing to them – rounding them up, not feeding them properly, putting them in buildings where infection was bound to spread, while ignoring calls for better funding.

By contrast, people who believed in social Darwinism, eugenics, or that other races were inferior, would assume or argue that Indigenous people happened to be more naturally susceptible to getting TB.

Bryce was right, and the others were wrong, because he understood actual medical science, and allowed new information to change his mind.

Eugenicists and people who believed in British Protestant supremacy, including Thompson Ferrier and J S Woodsworth, would not think that way. In his book promoting Residential Schools, Ferrier wrote “We who own their lands owe a duty to this perishing race.” – it is an assumption that Indigenous people in Canada are dying out.

Ferrier and Woodsworth are social Darwinians: they assume the society you happened to be born into reflects a fixed hierarchy that is a permanent reflection of nature. They assume that if you get sick and die, it is because of an internal, essential, unchangeable, hereditary flaw based in a stereotype of racial inferiority, and not that you have been weakened by being denied access to food.

Each human being is a combination of genes that has never existed before and will never again. There is no guarantee as to what traits may be passed down. Every person is a mix of their genes and their experience – but people are also self-aware and can guide and shape their own experience.

The idea of hard lines to define and divide groups based on culturally constructed ideas of identity makes no sense from a scientific point of view. Darwin himself continually warned against drawing too sharp of a distinction within and between entire species, because species are all related to each other, and connected through the entire web of life.

By contrast, social Darwinians don’t realize they are “born on third base but think they hit a triple.” They think that they are entitled to high social status and power because their accident of birth into a particular culture at a given time in history is seen as bring approved by “evolution” and nature, and not by politics, technology, law or finance.

Because they believe themselves to be superior, they believe they are entitled to preserve that superiority by treating the people they see as inferior as weak specimens to be culled from the herd, through both violence and neglect.

It is not just an ideology – it’s a mentality. It’s a way of thinking about the world that persists. Even when people admit that sterilization is wrong, they may still cling to the racist pseudoscience of ranking human beings and false ideas of inferiority and heredity.

And so, when present-day admirers want to praise Woodsworth and Douglas as pioneers and leaders, who despite their tiny numbers exercised a great influence on Canadian politics and social programs – they only want to talk about the good parts.

As Superintendent for the Methodist Missions across Western Canada, J. S. Woodsworth’s own father, James Woodsworth, lived in Brandon and was responsible for overseeing Ferrier and the Brandon Residential School. As mentioned above, the complaints against Ferrier kept coming.

“In 1915, parents refused to return children to the Norway House, Manitoba, school at the start of the school year because of complaints over the school’s lack of food and poor quality of clothing in the previous year. Methodist Church representative [Thompson] T. Ferrier reminded Chief Berens, “These children can be taken back to the school by the Department, in spite of whether the parents are willing or not now that they have been entered as pupils of the school.”

The Woodsworth and Ferrier families had deeper connections in running Residential Schools. Among Rev. Thompson Ferrier’s children was Russell T. (Thompson) Ferrier, who became director of education for the department of Indian Affairs.

J. F. Woodsworth was son of Superintendent James Woodsworth, and brother to J.S., the future CCF Leader. J. F. Woodsworth was a Principal at more than one Residential School. He and Russell T. Ferrier are both named as officials who were telling First Nations parents to persuade children to stay in school longer than the act required by law. They also sent police to recover children whose families did not want to send them to school.

“In 1914, “new Red Deer principal, J. F. Woodsworth, wrote letters to parents who had not sent their children back to school after the summer vacation that informed them that if the children were not returned within a week, “I shall send a policeman to bring them.” Later that month, he issued a warrant for the arrest of fifteen runaway students. By 1919, the school was in state of crisis brought on by chronic underfunding and a devastating bout of influenza.”

That influenza was the “Spanish Flu,” which killed millions around the world and was incredibly deadly on many First Nations. The death rate on some isolated reserves reached 95%.

“Although students could be withdrawn from school once they reached the age of sixteen, in the 1920s, the government policy was to encourage parents to keep their children in school until they turned eighteen. Russell T. Ferrier, the director of education for the department, wrote, “Indian Agents, principals and others interested in Indian education are urged to make every possible endeavor to persuade parents to leave their children in school for a longer period than prescribed by the Act.”

In February 1925, Russell Ferrier writes, arguing that medical officers need to do health checks, because when children get sick after admission, it drives down admissions.

“Russell T. Ferrier, Superintendent of Indian Education, writes to Indian commissioners and agents, saying each child should be pronounced fit by a medical officer before being admitted to a school. “When a pupil's health becomes a matter of concern soon after admission, the consequent parental alarm and distrust militates against successful recruiting.”

Russell Ferrier becomes “Superintendent of education” for the department but when asked for printed departmental regulations, says that there are none.

“The government’s general lack of policy seems to have been summed up in a 1928 letter from Russell T. Ferrier, then superintendent of education and a former senior official in the Methodist Missionary Society. Sister Mary Gilbert of the Grouard school in Alberta had written him to ask for “regulations concerning the education of Indian children.” Ferrier replied, “The only printed matter in this connection is the Indian Act, Section 9 to 11A inclusive.”

“There had been no doctor at all to visit the sick at Red Deer Industrial School that November. The Principal, J. Woodsworth, who had been ill along with the students and staff, sent along word to the Departmental Secretary, J.D. McLean, that five children had perished: Georgina House, Jane Baptiste, Sarah Secsay, David Lightning, and William Cardinal, who had died of the sickness “as a runaway from the school.”

Conditions were “nothing less than criminal. We have no isolation ward and no hospital equipment of any kind. “At the height of the sickness, without medical attention, “the dead, the dying, the sick and convalescent, were all together” in the same room. “You must,” he pleaded, “put this school in shape to fulfil its function as an educational institution. At present it is a disgrace.”

It was not the only disgrace. Because no one had recovered sufficiently to bury the children in the school cemetery, the Red Deer undertaker had to be summoned. Woodsworth assured McLean, however, that he had kept a watchful eye on expenses. ‘I directed the undertaker to be as careful as possible in his charge, so he gave them a burial as near as possible to that of a pauper. They are buried two in a grave.”

These are all people that J. S. Woodsworth knew - his father, brother, Thompson Ferrier and Russell T Ferrier. They promoted residential schools, ran them, and had firsthand experience of the hunger, sickness and deaths at Residential Schools. Thompson Ferrier knew that Dr. Peter Bryce had called the schools a “National Crime” and played it down. Ferrier’s son was hired into the Residential School bureaucracy.

As for J. S. Woodsworth’s response, he recommended eugenics and sterilizing the people he considered to be unfit.

J.S. Woodsworth and The Bureau of Social Research

The racist ideas Woodsworth was spreading in his book were not just parlor talk. According to a 2004 article in the Journal of Historical Sociology, Sterilizing the “Feeble-Minded”: Eugenics in Alberta, Canada 1929-1972, Woodsworth’s work directly informed the adoption of sterilization policies in Alberta.

“The eugenics platform was championed in western Canada by a number of influential social reformers including J. S. Woodsworth, a Winnipeg-based proponent of the “social gospel.” Woodsworth was concerned with the declining quality of immigrants arriving in the west. He translated his personal fear into a public crisis, spreading the idea that no segment of Canadian society would be left untouched by the influx of thousands of immigrants of inferior stock from central and eastern Europe. In time, his policy recommendations turned to eugenics and sterilization programs (Chapman 1977: 13).

Woodsworth was a core member of the Bureau of Social Research, an agency created by the provincial governments of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba and mandated to study social issues including child welfare, crime, and race and immigration problems.

Under Woodsworth’s influence the Bureau published articles about the “problem of the mental defective,” taking the eugenics position that mental defectiveness was hereditary and recommending the segregation and sterilization of mental defectives.”

Woodsworth was Secretary to the Bureau – which is to say, he was in charge. His appointment was announced in the Winnipeg Free Press, which published a number of the Bureau’s reports, with headlines like the one on October 11, 1916: “The Problem of the Mental Defective” which provided readers with a massive dose of pseudoscience, suggesting “feeble-mindedness” was hereditary.

“They are under a terrible handicap and are a tremendous moral, physical and financial burden on the homes to which they belong. the public schools which they often attend, and the society of which they form a part. They do constitute a grave national problem.”

In fact, much of what Woodsworth and the Bureau were peddling came from an outspoken Canadian eugenicist, Dr. Helen MacMurchy. Her intellectual and medical credentials were and are impressive. She earned her MD in 1901 and was “the first woman in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Toronto General Hospital, with a cross-appointment as lecturer at the University of Toronto, as well as the first woman accepted by Johns Hopkins University medical school for post-graduate study.” She went on to produce publications and shape the debate favouring the sterilization of the “feeble-minded.”

“This preoccupation with the feeble-minded swept the country… In Manitoba the 1913 Conference of Charities and Corrections devoted much of its attention to the issue. Three years later J.S. Woodsworth produced a series of articles on mental defectives for the Winnipeg Free Press that purportedly resulted from his investigations for the Bureau of Social Research. In fact, much of the material was taken straight out of MacMurchy's reports.”

Woodsworth’s articles led to Alberta’s 1928 eugenics laws. The Alberta Eugenics Board was active for the next 44 years, until it was dissolved in 1972. “From 1929 to 1972, when the Board was finally disbanded, the Board saw 4800 cases of proposed sterilization and approved virtually all (4739) of these. 2834 sterilization procedures were eventually performed, the majority on females.”

When people say that eugenics were broadly accepted, it is true – but it was never universally accepted, and there were always people who strenuously opposed it. This is retroactive justification for people holding these beliefs when clearly, if support for eugenics had truly been so widespread, more provinces in Canada would have passed eugenics laws, but only two did – British Columbia and Alberta.

Many of Canada’s protestant denominations supported and even promoted eugenics. It is often mentioned that prominent figures like Nellie McClung and Emily Murphy of Canada’s Famous Five, who both helped ensure women were recognized as full persons under the law, both endorsed eugenics. Emily Murphy’s husband was a Reverend in the Anglican Church, and McClung was a Methodist.

The Methodist Church in particular adopted and promoted eugenics. In 2016, the United Methodist Church in the US issued a statement of repentance for its historic support and promotion of eugenics:

“Methodist bishops endorsed one of the first books circulated to the US churches promoting eugenics. Unlike the battles over evolution and creationism, both conservative and progressive church leaders endorsed eugenics. The liberal Rev. Harry F. Ward, professor of Christian ethics and a founder of the Methodist Federation for Social Service, writing in Eugenics, the magazine of the American Eugenic Society, said that Christianity and eugenics were compatible because both pursued the “challenge of removing the causes that produce the weak.”2

“Ironically, as the Eugenics Movement came to the United States, the churches, especially the Methodists, the Presbyterians, and the Episcopalians, embraced it.

Methodist churches around the country promoted the American Eugenics Society “Fitter Family Contests” wherein the fittest families were invariably fair skinned and well off.

Methodists were active on the planning committees of the Race Betterment Conferences held in 1914, and 1915.4 In the 1910s, Methodist churches hosted forums in their churches to discuss eugenics. In the 1920s, many Methodist preachers submitted their eugenics sermons to contests hosted by the American Eugenics Society. By 1927, when the American Eugenics Society formed its Committee on the Cooperation with Clergymen, Bishop Francis McConnell, president of the Methodist Federation for Social Service, served on the committee. In 1936, he would chair the roundtable discussion on Religion and Eugenics at the American Eugenics Society Meeting.

The laity of the church also took up the cause of eugenics. In 1929, the Methodist Review published the sermon “Eugenics: A Lay Sermon” by George Huntington Donaldson. In the sermon, Donaldson argues, “the strongest and the best are selected for the task of propagating the likeness of God and carrying on his work of improving the race.”

The ideas behind eugenics were, unsurprisingly, racist from the start, especially towards Blacks and Indigenous people. They were promoted by members of Charles Darwin’s family, including his cousin, Francis Galton:

“In an article entitled “Hereditary Character and Talent” (published in two parts in MacMillan’s Magazine, vol. 11, November 1864 and April 1865, pp. 157-166, 318-327), Galton expressed his frustration that no one was breeding a better human:

“If a twentieth part of the cost and pains were spent in measures for the improvement of the human race that is spent on the improvement of the breed of horses and cattle, what a galaxy of genius might we not create! We might introduce prophets and high priests of civilization into the world, as surely as we can propagate idiots by mating cretins. Men and women of the present day are, to those we might hope to bring into existence, what the pariah dogs of the streets of an Eastern town are to our own highly-bred varieties.”

Galton in the same article described Africans and Native Americans in derogatory terms making it clear which racial group he thought was superior.”

Treating Africans and Native Americans as inferior – as less than full people - helped justify taking their lands in the 1800s, as European powers reached around the globe, empire-building everywhere they went.

Charles Darwin himself made eugenicist arguments in The Descent of Man: "With savages, the weak in body or mind are soon eliminated; and those that survive commonly exhibit a vigorous state of health. We civilized men, on the other hand, do our utmost to check the process of elimination; we build asylums for the imbecile, the maimed, and the sick: we institute poor-laws; and our medical men exert their utmost skill to save the life of every one to the last moment. There is a reason to believe that vaccination has preserved thousands, who from a weak constitution would formerly have succumbed to small-pox. Thus the weak members of civilized societies propagate their kind. No one who has attended to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that this must be highly injurious to the race of man. It is surprising how soon a want of care, or care wrongly directed, leads to the degeneration of a domestic race; but excepting in the case of man himself, hardly any one is so ignorant as to allow his worst animals to breed” (The Descent of Man, p. 873).

It's worth pointing out while Darwin voyaged the world, he is also writing in the middle of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, when there was plenty of shocking deprivation and poverty. On the one hand, it made Britain the world’s largest exporter, with 50% of all the manufactured goods in the world were being made in Britain. On the other, inequality, poverty, and shockingly dangerous work conditions actually resulted in life expectancy dropping lower than it had been for centuries. “In poor areas of Manchester, life expectancy was seventeen years' - 30% lower than what it had been for the whole of Britain before the Norman Conquest, back in 1000 (then twenty-four years).”

In the early 1900s, people of a wide range of views found common ground on a handful of issues – women getting the right to vote, prohibition of liquor, and the need for eugenics. Progressives, activists and even extremists were all driven by an early variation of the “replacement theory” – that British (or American) protestants would be outnumbered or outbred. In Canada and the US, those groups included people who were fighting for women’s rights, certain protestant churches, farmer’s political parties, and the Ku Klux Klan.

Eugenics becomes Policy: Alberta

100 years ago, the 1920s are thought of as a decade of prosperity and growth. That’s not exactly true. In some ways, the “roaring” 1920s were like the last decade - the 2010s - stock markets and low interest rates created a boom economy for the rich and ultra-rich, and people were going into debt to buy their needs.

This created social pressures that led to the collapse in support for old parties and fracturing into new ones, as well as more extreme ideas and movements.

The United Farmers had provincial associations and formed successful political parties – and surprise governments, in both Alberta and Manitoba. In 1921, the UFA formed a majority government, and in the 1921 Federal election, Progressive and UFA candidates took most of the seats in Alberta, with the remaining two going to labour. There was support for eugenics among the Progressives and UFA.

One of those elected MPs was William Irvine, who won as a Dominion Labour candidate for Calgary East. J. S. Woodsworth was elected as well, in the riding of Winnipeg Centre. Irvine was, and remained, a close friend of Woodsworth’s: as mentioned above, Irvine had originally been brought to Canada by James Woodsworth, and had an interest in Social Credit theories of finance – so called “monetary reform.”

The idea of social credit was developed by Major Douglas in Britain. Douglas had been tasked with an analysis of industrial finances and was struck that it seemed mathematically inevitable that workers were never going to be paid enough to buy goods and keep the economy afloat. He proposed a kind of universal income scheme. In the notes to his General Theory on Employment, John Maynard Keynes said some of the analysis and proposals in social credit had merit, but Douglas was later deeply discredited by his antisemitic conspiracy theories. He blamed “International Jewry” and so did many of his followers.

In 1923, Woodsworth and Irvine, as Members of Parliament, had invited Major Douglas, the chief theorist of Social Credit, to Canada to speak to the House of Commons. They also invited the automobile magnate Henry Ford. A biography of Irvine from the 1970s, written by a friend and fellow socialist, Anthony Mardiros, explains Ford’s invitation:

“Henry Ford at that time was interested in monetary reform and had written in his own newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, on this subject. For publicity reasons, Irvine and his friends wanted him to come to Ottawa and give his views to the committee. In order to persuade Ford to come, Irvine made a trip to Dearborn. He travelled by rail on his MP's free pass… At Dearborn, Irvine met Ford only to discover that he had become preoccupied with the notion of running for President of the United States, and he had also, to Irvine's disquiet, developed a nasty strain of anti-Semitism.”

It is, to say the least, hard to believe that anyone who had read the Dearborn Independent would be surprised by Ford’s antisemitism, which had been on full public display for several years. “In 1920, Ford began publishing a weekly series called “The International Jew: The World’s Problem” on the paper’s front page. The series was based on an antisemitic hoax known as The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which purported to reveal a global Jewish conspiracy for money and power.” That same antisemitic conspiracy theory also made its way into Major Douglas’ Social Credit books in the 1930s.

In 1926, Irvine switched to the UFA as a candidate in 1926, when he was re-elected as MP. In 1928, the provincial UFA government in Alberta introduced its eugenics sterilization bill that had been inspired by J.S. Woodsworth’s work at the Bureau of Social Research.

In 2019, Erna Kurbegović wrote a PhD thesis comparing how Manitoba and Alberta diverged on the subject of eugenics and sterilization laws. There were debates in both provinces, driven partly by the United Farmer’s Women’s Associations in each province, but while Alberta passed their Sexual Sterilization Act in 1928, Manitoba rejected a similar bill in 1933, as well as other attempts to bring it back as late as 1940.

Read Chapter 1 - Riel Vs. Scott

Read Chapter 2 - Methodists, Woodsworths, and Residential Schools