The Great Deception Chapter 6 - How a KKK Organizer Helped Elect the “Greatest Canadian”

In 1933, Tommy Douglas wrote a thesis promoting eugenics, and in 1935 was elected with the help of KKK Organizer for Western Canada, Daniel Carlyle Grant.

The legend of Tommy Douglas is that he was a young idealistic preacher, so shocked by the misery and suffering of people during the Depression in Saskatchewan that he left the pulpit for politics, and embraced socialism, as if he were converted. That is the entire premise of a book of interviews with Douglas in the 1950s, published as “The Making of a Socialist.” It is also the character arc suggested by the made-for-tv CBC fictionalization of Douglas’ life, Prairie Giant:

“In 1930s Saskatchewan, a small town parish has a new young new pastor, Tommy Douglas. However, for all his regular duties, which include boxing lessons, Tommy sees the poverty and injustice around him which seem beyond his power to address with the pulpit. With that in mind, Douglas enters politics with the socialist Canadian Commonwealth Federation and starts a career where his steadfast idealism runs headlong into the powerful opposition of the rich and the powerful. Despite the long odds, Douglas’ new calling would soon make him a leader that would transform Canada and have him hailed as the greatest Canadian of all.”

This is an effort to create an “origin story” for Douglas that is at odds with the facts.

We do know that in Weyburn, Douglas was working on employment issues, and he was also working at the Weyburn Mental Hospital, where he was working on his thesis, because Douglas, like many in the CCF, were academics and preachers.

At the employment office, he was dealing with Daniel Carlyle Grant, the former KKK organizer for all of Western Canada, who had been given the post as a patronage appointment for helping elect a Conservative Government in Saskatchewan in 1929. That is the same Daniel Carlyle Grant who spent his time spreading hate in Winnipeg and across Manitoba, before returning to Saskatchewan to work as a driver for the head of the KKK there.

At the Weyburn Mental Hospital, Douglas was observing people for case studies for his Masters’ Thesis, which was on the problems of the subnormal family, to which Douglas’ solutions included segregation and sterilization.

Tommy Douglas and Eugenics

Contrary to the idea that Douglas’ support of eugenics was a brief flirtation, quickly forgotten, the topic is identical to J.S. Woodsworth’s work with the Bureau of Social Research – that “mental defectiveness was hereditary and recommending the segregation and sterilization of mental defectives.” J. S. Woodsworth was not only CCF MP and leader – he was Tommy Douglas’ family preacher growing up.

In 2011, Michael Shevell wrote a paper in The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences entitled “A Canadian Paradox: Tommy Douglas and Eugenics.” The “paradox” that Shevell refers to is that contradiction between Douglas’ stated values he claims inspired him as a politician of the left, supposedly standing up for the oppressed, with his recommendation that “subnormal families” be either segregated into camps or sterilized.

Shevell writes that Douglas’ “iconic, indeed mythic, status within the Canadian historical landscape is exemplified by his selection, in 2004, as “The Greatest Canadian” in a CBC mandated competition above such luminaries as former Prime Ministers Pierre Elliot Trudeau and Lester Bowles Pearson, scientist Frederick Banting, and hockey great Wayne Gretzky.”

Shevell concludes that Douglas’ views were only “briefly held” – though a deeper dive into the evidence suggests otherwise. For many Canadians, this creates not just a paradox, but cognitive dissonance: because Douglas is hailed as a hero, his commitment to forced sterilization is ignored, minimized or suppressed.

This is reflected in works of popular history. One fairly typical example is the treatment of Douglas in Canada’s History. It featured a profile of Tommy Douglas from 2010 as a “History Idol” where Douglas’ past is presented entirely uncritically. The person presenting Douglas’ story is Margaret Conrad, “an honourary research professor at the University of New Brunswick. She became an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2004 and is a director of Canada’s History Society.” Conrad’s story is one of personal conversion – she saw Douglas speak as a young Progressive Conservative in the 1960s and was immediately convinced - it is not impartial or historical, it is communicated by a political convert.

In Penguin Canada’s series “Extraordinary Canadians” Douglas’ biography is told by Vincent Lam, a physician who won one of Canada’s major literary prizes, the Giller. When Duncan McMonangle reviewed the book in the Winnipeg Free Press, he said “Lam's generous account frequently veers toward hagiography.”:

“Lam deals with Douglas's most controversial view, an advocacy of eugenics that was not uncommon in the 1930s, in a mere three paragraphs. In his master's thesis, The Problems of the Subnormal Family, Douglas argued for sterilizing the “mentally defective and incurably diseased.”

Such notions are abhorrent in today's Canada and eugenics has no scientific basis; Lam makes clear.

But he argues that Douglas was simply imagining a better world. In office, the practical politician repudiated those views.”

These are typical responses – and typical in a couple of ways. Lam minimizes Douglas’ eugenics, but so does the reviewer, claiming that Douglas’ “advocacy of eugenics was not uncommon in the 1930s.”

We are told, in effect, that there is nothing to see here, and that there was nothing out of the ordinary or exceptional. The fact that only two of Canada’s provinces ever passed a eugenics sterilization law – Alberta and British Columbia –makes it clear that it was a view that was rejected in eight out of ten of Canada’s provinces, including the most populous provinces of Ontario and Quebec.

Douglas’ endorsement of eugenics is very clear and steeped in the pseudo-science of the age. Douglas’ thesis topic, in his own words:

“The subnormal family is an ever-increasing menace physically, mentally and morally, to say nothing of a constantly rising expense … Surely the continued policy of allowing the subnormal family to bring in to the world large numbers of individuals to fill our jails and mental institutions and to live upon charity is one of consummate folly.”

He starts his thesis this way:

“The problem of the subnormal family is chiefly one for the State… Since the state has the problem of legislating in the best interests of Society, and since we have seen that the subnormal family is an ever-increasing menace physically, mentally and morally, to say nothing of a constantly rising expense, it is, surely the duty of the State to meet this problem.

The suggested remedies which the state might effect are three in number:

1) The Improvement of Existing Marriage Laws;

2) Segregation;

3) Sterilization of Unfit, and Increased Knowledge of Birth Control.”

He elaborates:

“3) Sterilization of the mentally and physically defective has long been advocated, but only recently has it seeped into the public consciousness. From the day when Plato wrote his Republic to the present, eugenicists have advanced various solutions to the problem of the defective, but sterilization seems to meet the requirements of the situation most aptly.

For while it gives protection to society, yet it deprives the defective of nothing except the privilege of bringing into the world children who would only be a care to themselves and a charge to society.

4.) Another effect if the abnormal family is the cost of maintenance: It may be a mercenary view to take of the problem, yet in view of mounting taxation, it is of importance to the average citizen to know the effect of the subnormal family on his tax bill.”

This last sentence bears repeating. Tommy Douglas wrote:

“in view of mounting taxation, it is of importance to the average citizen to know the effect of the subnormal family on his tax bill.”

Douglas is arguing we need to consider sterilizing people to keep taxes from going up. This is beyond mercenary.

This is also not an offhanded comment in an interview with a reporter. It takes time to research and write a thesis, and if Douglas wanted another topic, he could have chosen one.

Nor did Douglas just write his thesis and let the matter drop. As Michael Shevell writes, “It is interesting to note that the themes and conclusions put forward by Douglas in his MA thesis would be repeated in a Douglas authored 1934 CCF Research Review entitled “Youth and the New Age”.

In fact, Douglas was the head of the party’s youth wing when he made the proposal. In Building the New Society, Dave Marshes writes that even before his decision to run for member of parliament in 1935, J.S. Woodsworth had appointed Douglas to the Youth wing to help suppress leftists.

“Tommy had become a national leader of the party. At the CCF convention in Winnipeg the previous summer, Woodsworth had asked Tommy, then not quite thirty, to head up the party's youth wing in order to quell a revolt from the left. Tommy became convinced that the agitators were communists intent on taking over the CCF or breaking it up.

The conspiratorial idea that the CCF were going to be taken over or broken up by communists should be taken as a grain of salt - but the push back against the left has been a common theme throughout the history of the CCF and the NDP, with more conservative elements consistently marginalizing the left, even as they campaign on left-populist ideas.

There is a significant difference between communists wanting to take over the CCF on the one hand or breaking it up on the other. “Breaking up” the CCF suggests that the leftist youth were, in effect, communist double agents, trying to undermine the CCF from within, with the goal of destroying the movement. They are a threat to the entire project, because they are operating on the basis of malicious intent. “Taking over” however, is a different kind of threat entirely: it’s a threat to the people in charge, not the party - it’s that people want to see their ideas implemented, which is the purpose of political parties.

This “shift to the right” is sometimes depicted as moderation, or as a move to the centre, when those ideas can overshoot the centre entirely and be conservative.

There are two reasons we don’t see this in the Canadian political context, and they are both based on perception rather than reality.

One, which is important, is that there has long been a far-right element in Canadian politics, especially in Western Canada - who even portray genuine moderate centrists as being far left and radical, and a threat. The fact that communists in the USSR banned religion meant that Christians would obviously see communism as hostile.

It’s common enough to tar all opponents with the same brush, but the perspective that the CCF and NDP parties or Liberals were radical or far left, is only because the critics are so far out to the right.

Shevell’s paper comments on the apparent “Canadian paradox” of a figure of Douglas’ reputation having such views. The question is not why there is a paradox, but why we think there is one.

What is happening is “cognitive dissonance” : people are uncomfortable because they’ve got two conflicting ideas in their heads, and the conflict is because the CCF and NDP, and Tommy Douglas in particular, are supposed to be in some way different.

It may be that this is partly based on the idea of the social gospel - that, as preachers, they had higher moral standards and greater authority than other politicians, when perhaps - just perhaps - they are politicians like any other. The reality is that, CCF and NDP politicians alike said one thing and did another.

Shevell’s response, like that of so many others, is to justify it.

Shevell noted that that

“Douglas was not a lonely socialist in his support of eugenics. He was joined by such international luminaries of leftish opinion as JS Haldane, Sydney and Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw, and HG Wells amongst others.”

The fact that other “prominent” individuals supported eugenics gives the ideas a credibility and dignity they don’t deserve.

We don’t have to evoke – or dignify – eugenics, especially by naming figures like H.G. Wells and Bernard Shaw. On the most fundamental terms of evaluating evidence, this is a logical fallacy – the appeal to authority, which in today’s world we might reframe as an “appeal to celebrity.” Just because someone is an expert in one thing – writing captivating stories or plays, like Wells and Shaw – it does not mean they have any expertise or authority in anything else.

Roping H G Wells, Bernard Shaw and Tommy Douglas together on the issue of forced sterilization does not do Douglas any favours.

Wells’ and Shaw’s reputations have been rightfully tarnished by their atrocious judgment on these issues. Wells’ eugenics were extreme and explicitly genocidal. He called for wide ranges of vulnerable people to simply be put to death, including alcoholics, and entire races.

As for Shaw, his brilliance at literary invention should not be confused with having exceptional political or scientific insight. Shaw was one of many “useful idiots” for the Soviet Regime who were duped in 1932 into reassuring the world that there was no famine in Ukraine, at the very time that the USSR was starving millions of Ukrainians to death during the Holodomor. Shaw was complicit in covering up a genocide.

As others have pointed out, eugenics in Alberta was supported by Emily Murphy and Nellie McClung, two of the “Famous Five” responsible for the “persons case” where women in Canada were formally recognized by the law as a “person”. Nellie McClung also played a key role in obtaining votes for women in Manitoba in 1916, the first province to recognize the franchise for women in Canada. These are both landmark achievements in the advancement of rights for some women in Manitoba and Canada.

Both Murphy and McClung were exceptional writers, with some exceptionally bad ideas. Murphy wrote under the pen name “Janey Canuck” for Macleans magazine, in articles blaming Blacks and Chinese for drugs and criminality in racist terms. McClung promoted eugenics in books.

Many know that McClung and Murphy supported eugenics, and their historical stature seems diminished as a consequence. Tommy Douglas’ support for eugenics is treated as a puzzle, while J.S. Woodsworth’s is unspoken.

It boils down to the fact that people simply don’t want to accept it, so the reaction to Woodsworth’s and Douglas’ direct and vocal support for sterilization is usually met with “whataboutism” - which according to Merriam Webster is:

“the act or practice of responding to an accusation of wrongdoing by claiming that an offense committed by another is similar or worse

The exchange is indicative of a rhetorical strategy known as whataboutism, which occurs when officials implicated in wrongdoing whip out a counter-example of a similar abuse from the accusing country, with the goal of undermining the legitimacy of the criticism itself.—Olga Khazan

By whataboutism I mean the way any discussion can be short-circuited by saying "but what about x???" where x is usually something that's not really equivalent but is close enough to turn the conversation into mush.—Touré

McClung and Murphy were hugely influential, but unlike J.S. Woodsworth and Tommy Douglas, they did not found political parties whose entire brand is supposed to be standing up for the little guy, not rounding up the little guy, putting them in camps, and sterilizing them.

Douglas’ thesis recommending sterilization was not a momentary lapse in individual judgment – he was surrounded by people who believed the same thing. The core founders and leaders of the CCF and the NDP were all implicated in eugenics and sterilization.

J. S. Woodsworth’s writings promoted eugenics, leading to Alberta adopting sterilization. Tommy Douglas wrote a thesis on the same subject. Saskatchewan Progressive MLAs also called for sterilization. In Alberta, William Irvine was a UFA politician, whose party brought in eugenics laws. Irvine: he was brought to Canada by James Woodsworth, remained a good friend of J.S. Woodsworth, and the meeting where it was decided to form the CCF was held in his parliamentary office.

While it’s often said that Douglas is supposed to have renounced his 1933 views on eugenics, it is unclear when. In 1934, he put the ideas forward again in a CCF publication. People often argue, as did Vincent Lam, that Douglas repudiated his views once in office.

It’s been suggested that Douglas abandoned his views after the Second World War ended in 1945, while others have suggested that he had his mind changed by a trip to Germany in 1936, from which he supposedly returned a changed man. In 1936, Douglas had already been a member of parliament for a year.

Douglas’ own statements about his trip to Germany suggests that it had no impact on his views on eugenics. From Making of a Socialist:

“You were in Europe for how long?

About three months. We went from Switzerland to Nuremberg, because I wanted to see the great annual festivity Hitler put on each year there. It was frightful. I came back and warned my friends about the great German bombers roaring over the parade of self-propelled guns and tanks, Hitler standing there giving his salute, with Göring and the rest of the Nazi bigwigs by his side.

There was no doubt then that Hitler was simply using Spain as a dress rehearsal for an attack on other nations.

It was with very great difficulty that people were able to appreciate the anti-Semitism that was going on in Germany. Did you yourself see any examples of it?

I didn't see any. Most of it was over by the time I got there.”

Unlike Douglas, many politically aware people didn’t need to attend a 1936 Nuremberg Rally in person to figure out that Hitler was a dangerous hatemonger who posed a threat to the world. One of the major figures who warned against Hitler was Alexander Dafoe, the Editor of the Winnipeg Free Press.

Part of Douglas’ having to be noisy about warning his friends about Hitler’s threat is that J. S. Woodsworth, as leader of the CCF, had opposing Canada’s participation in the war. It has been characterized as highly principled, but certainly questionable judgment in view of Hitler’s openly genocidal policies.

It’s also startling for Douglas to suggest that most of the antisemitism in Nazi Germany was over by the 1936, considering Kristallnacht and the Holocaust both lay ahead.

It’s clear from his 1958 interview in the Making of a Socialist that Douglas does not want to tell the full truth about his thesis, when he tells the interviewer:

“During this period I was working on my master's thesis from McMaster University. I had decided to write my thesis on the problems of the subnormal family, under the general topic of Christian sociology.”

That Douglas would pass his thesis on eugenics off as “Christian Sociology” is intriguing – which is to say, did he really believe that sterilizing people who are subnormal is “Christian Sociology”?

Daniel Carlyle Grant and the 1935 Douglas campaign

It is very clear that even historians struggle with the idea that the CCF’s values were incompatible with eugenics, based on the party’s well-crafted, post-success brand as champions of the underdog. The fact that Douglas was elected in 1935 with the help of one of the Ku Klux Klan’s Organizers creates cognitive dissonance so intense it could be measured with the Richter scale.

In his book, The Ku Klux Klan in Canada, Allan Bartley, writes

“Daniel Carlyle Grant, the Klan worker rewarded by the Conservative Saskatchewan government in 1929 with a job in Weyburn, did not fare well as the Depression hit its depth. The new Liberal government fired him in 1934. Grant wanted revenge, and he sought it by working for Tommy Douglas, the firebrand candidate representing the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), a political formation that found Klan ideals abhorrent.”

Bartley is assuming – and he is offering - a rationale that creates a both a defense for the CCF and sympathy and supposed understanding for Grant.

It’s true, that there is no reason to believe that Douglas was aware of speeches like this one, given by Grant on October 16, 1928, at the Norman Dance Hall on Sherbrook in Winnipeg, where, he told an audience of 150 that:

“The Klan strove for “racial purity. We fight against intermarrying of Negroes and whites, Japs and White, Chinese and Whites. This intermarriage is a menace to the world. If I am walking down the street and a Negro doesn’t give me half the sidewalk, I know what to do.” He then lashed out at the Jews and said that “The Jews are too powerful ... they are the slave masters who are throttling the throats of white persons to enrich themselves.” Grant claimed that the federal Liberal government was allowing the “scum of Papist Europe to flood the country and refuse to allow immigrants into the country who are not Roman Catholic ...”

Clearly, not everyone in the CCF found Klan ideals “abhorrent” – they shared many of them – eugenics, sterilization, prohibition, and a protestant opposition to, and even hatred of, Catholicism.

And surely, if the KKK was so problematic, a principled and idealistic man like Tommy Douglas would never take Daniel Carlyle Grant, KKK organizer, to be a key figure in his 1935 campaign for CCF Member of Parliament.

One of the defining features of propaganda as history – and why we believe it - is that for many it can be more palatable to believe ludicrous but reassuring lies than to face up to harsh truths.

Many of the reports of Daniel C. Grant’s decision to work for Douglas have a twinge of sympathy about them. When Bartley describes Daniel Carlyle Grant as not faring well and saying that he “wanted revenge” treats Grant as the victim who is in the right.

Revenge? For being fired by a Saskatchewan Liberal government that didn’t want KKK organizers working in the employment bureau? Grant was in charge of jobs in the Depression in Saskatchewan, a job he obtained by being an KKK organizer. What are his hiring practices going to look like?

This framing appears to be that this poor fellow found himself unemployed in the middle of the Depression in Saskatchewan, after the Liberals were re-elected. Unlike many, he had actually had a government job for the first four years of the Depression. And Grant was fired for the same reason he was hired in the first place: he was a KKK organizer who spent years making money selling the vilest kind of hate.

Who, in painting Carlyle as a victim, is on the right side of history?

The Liberals are the ones who thought that KKK organizer and hatemonger didn’t belong in politics or working for government. Tommy Douglas is the one who disagreed.

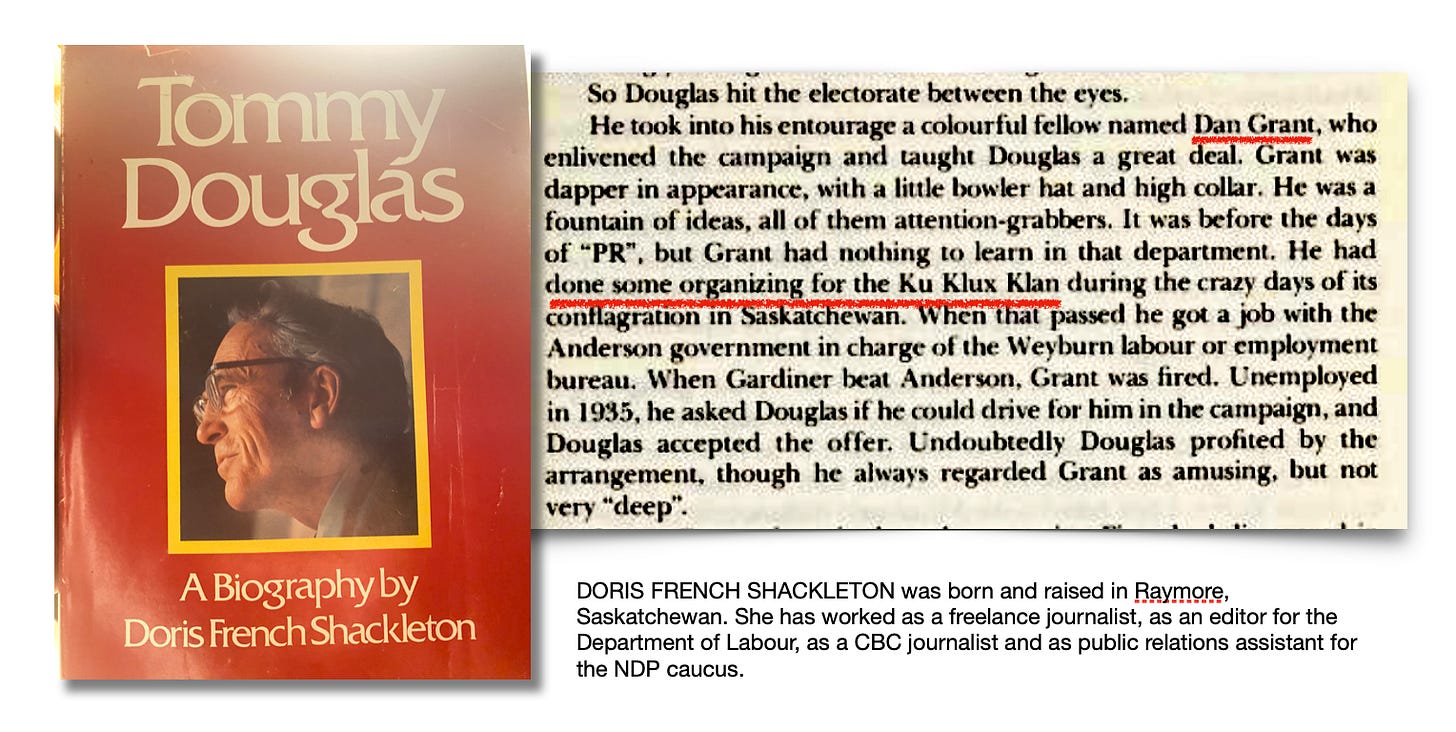

The fact that Grant was a KKK organizer is freely conceded in a 1974 biography of Douglas Tommy Douglas, by Doris Shackleton. Shackleton was “was active in the CCF youth movement in the province and she worked as a teacher before moving in 1945 to Ottawa. There, she worked as a freelance journalist, then as an editor for the Department of Labour, as a journalist for the CBC, and, in 1971, as public relations assistant to the NDP caucus.”

“[Tommy Douglas] took into his entourage a colourful fellow named Dan Grant, who enlivened the campaign and taught Douglas a great deal. Grant was dapper in appearance, with a little bowler hat and high collar, He was a fountain of ideas, all of them attention-grabbers. It was before the days of “PR”, but Grant had nothing to learn in that department. He had done some organizing for the Ku Klux Klan during the crazy days of its conflagration in Saskatchewan. When that passed he got a job with the Anderson government in charge of the Weyburn labour or employment bureau. When Gardiner beat Anderson, Grant was fired. Unemployed in 1935, he asked Douglas if he could drive for him in the campaign, and Douglas accepted the offer. Undoubtedly Douglas profited by the arrangement, though he always regarded Grant as amusing, but not very “deep”.

Margoshes book clearly draws from Shackleton, and says much the same thing.

By contrast, in “The Making of a Socialist” Douglas speaks at length about the campaign, about Grant and his impact, but never mentions the link to the KKK, even when pressed about Grant’s background. The book is a series of transcribed interviews conducted in 1958 with political journalist Chris Higginbotham.

“[Higginbotham] “Where did your friend Mr. Grant come from?

[Douglas:] He had been in Weyburn. Prior to becoming unemployed he was in charge of the Labour Bureau for the Anderson administration.

The provincial government kept a labour office, then after the Liberals came in, in 1934, he was dismissed and without a job.

Did you know anything about his background?

Very little. When he had been in the provincial labour office in Weyburn, I used to have quite healthy battles with him over relief schedules and things of that sort. But it wasn't until the election that I got to know him quite well, and grew to be very fond of him.”

For many reasons, it is difficult to believe that Douglas was unaware of the KKK association - especially given the fact that it was openly disclosed in another Douglas biography, which was first published in 1975, when Douglas was still alive.

Grant helped Douglas in every way: he was a fundraiser for his campaign, taking donations through a lottery for a campaign car that could be used during the campaign, then awarded at the end. He gave Douglas communications advice - taught him how to focus on “wedge issues,” created pamphlets and taught Douglas not to use “academic” speeches but to tell funny stories.

This technique was drawn right from the Klan campaign playbook. As historian James Pitsula wrote:

“The Klan offered a populist type of British Protestant nationalism, such as the Orange Lodge did not provide. The Klan went out to the people. It held public meetings and sent out charismatic lecturers, almost in the style of evangelical preachers. It created drama and excitement with a hint of romance and danger. Crosses burned on dark hillsides, fiery spectacles visible for kilometres around. There was something darkly primitive about the Klan, and yet it also had a comic side. Klan lecturers told funny stories and used humour as a weapon. A Klan rally was entertaining, vulgar but not boring.”

As Shackleton described it, Douglas had “discovered political shorthand,” but the way in which the story is presented is doubly dishonest and deceptive. She writes:

“You cannot explain at length to thousands of people. You cannot tell them in detail how the Liberals, as he believed, were restricting the economy instead of expanding it to meet the challenge of the depression. One significant statement had to say it all.

He would be accused of being simplistic. He mastered the art of finding the one exciting circumstance that immediately transfers a whole body of fact.

He learned in 1935 that drama belongs in politics, that it is a political crime to be dull. He had been a fervent and compelling preacher, and he had been a skilled entertainer. He put the two parts together.

“I began telling jokes,” Douglas said, “because those people needed entertainment. They looked so tired and frustrated and weary. The women particularly. They had all the back-breaking work to do. So I used to tell the jokes to cheer them up.”

“And when they're laughing they're listening.”

The first misleading statement is subtle, because saying that Douglas “had discovered political shorthand” shifts responsibility for learning these campaign techniques away from Grant, and makes it seem as if Douglas developed them himself. Grant, after all, had seen and used campaign techniques of the Klan up close and first hand – both as a recruiter himself and as a bodyguard and organizer for the KKK’s leader J. J. Maloney.

The other misleading statement is a significant error in fact and history: when Shackleton says, “the Liberals, as he believed, were restricting the economy instead of expanding it to meet the challenge of the Depression,” is untrue for the simple reason that the Liberals were not in power or running the government.

In the 1935 election, the incumbent government of Canada was Conservative, not Liberal. The Prime Minister was R. B. Bennett. The Liberals, led by Mackenzie King, were the opposition, seeking to defeat the Conservatives, which they did.

When you consider who Douglas and Shackelton reflexively see as allies and opponents in the 1935 campaign, it is revealing. The party that had been running Canada for the first years of the Depression were the Conservatives. But Shackleton has Douglas blaming the Liberals. Douglas and his campaign aren’t modern-day progressives aligning with Liberals against conservatives – they are anti-Liberal, and aligning themselves with everyone else who was, too.

For Douglas and the CCF, this is a regular pattern. In the 1938 provincial election in Saskatchewan, the opposition parties were despairing at the possibility of another Liberal victory. Douglas, in The Making of a Socialist, says:

The “provincial election in 1938 … That was a terrible schemozzle from our standpoint. George Williams got the idea that the government would be almost impossible to defeat, and that to prevent the C.C.F. from being annihilated, he should enter into an arrangement with the Conservatives and the Social Crediters to saw off seats. The result was that we only ran thirty-one candidates.”

This is an interesting comment from Douglas, because the strategy is exactly the deal that the Progressives (and Douglas’ mentor M. J. Coldwell) had used effectively to get into a Coalition with the Conservatives in 1929. However, it’s also clear that Douglas has an axe to grind – because Williams tried to get Douglas removed as a candidate in the election he had won in 1935.

That’s because not only did Douglas have a KKK organizer as a driver, fundraiser, advisor, and organizer in Grant, Grant successfully secured an endorsement from Bill Aberhart, the recently elected far-right Social Credit Premier of Alberta.

The endorsement from a Premier of a party some saw as fascist nearly got Douglas fired as a candidate, but may have also won him the election.

Social Credit was seen as a hard core ultra-right party. Aberhart was a radio preacher and evangelical who had worked with the United Farmers of Alberta before coming across some Social Credit theories of guaranteed income. There were a couple of problems with the whole scheme. One was that social credit as a movement was undermined by the antisemitic conspiracy theories of its proponent, Major Douglas. Another was that for the scheme to work, it would have to be legal for the province of Alberta to print its own money, which it is not. That did not stop Aberhart from trying.

“Political sleight of hand worthy of Watergate”

There are different accounts of just how Social Credit was involved in Douglas’ campaign, but Bible Bill Aberhart was dragged into Tommy Douglas’ 1935 campaign for MP in Saskatchewan, because there had been a rumour that the Liberals were going to pay a phony Social Credit candidate to run to split the vote. Grant took the news to Aberhart, who was appearing in Regina. Aberhart agreed that if the candidate was fake, he would denounce them and endorse Douglas instead.

Aberhart’s endorsement caused a split in the CCF party, with farmers and labour calling for the CCF to cut ties with any candidate who was endorsed by Social Credit. One CCF candidate, Jacob Benson of Yorkton, “lost his farmer-labour credentials.”

Tommy Douglas was spared by M.J. Coldwell, who was now the CCF Party President in Saskatchewan, and was also running as a candidate for MP. Here is Douglas telling the story himself in The Making of a Socialist.

“[Daniel C Grant] said, “I'm going to talk to Aberhart.” So off he went. He told Aberhart that if the Social Credit wanted to run a candidate against me, that was their business and their privilege, but that he did object to the Social Credit party allowing its name to be used by the Liberal dummy candidate.

Aberhart got quite indignant, said he certainly wouldn't stand for this, and asked, “Would Douglas run as Social Credit?” Grant said, “Certainly not.” Then he said,

“Are there any Social Crediters there at all?” Grant said. “There may be some, I think we could find them.”

“Well,” said Aberhart, “would the Social Credit people there endorse this candidate? Because if they will, I will denounce this Liberal stooge as a fake.”

So Grant came back to the Weyburn constituency and rounded up twenty or thirty people who proceeded to hold a Social Credit convention, at which they said there wasn't any Social Credit candidate running, and that they had written authority from Mr. Aberhart to say that the alleged Social Credit candidate wasn't Social Credit at all, but was being financed by the Liberal party. They called on any Social Crediters in the constituency to support me. This was published and played up by the press that I was running as the C.C.F. Social Credit candidate.

But at no time was I ever in any way associated with the Social Credit party, except that I did accept their endorsement and their C.C.F politician support, although there weren't actually many Social Crediters in the constituency.”

None of this denial makes any sense. His campaign went out of their way to secure a Premier’s endorsement, including staging a fake meeting pretending to be another political party. All that even though there weren’t many Social Crediters?

Shackleton’s book Tommy Douglas tells a slightly different story.

She makes it quite clear that the Social Credit meeting to denounce the phony candidate was a sham – the “Social Credit convention” was “packed, it was said, with CCFers” who repudiated the Social Credit candidate and endorsed Douglas instead. In today’s terms, this would be “astroturfing” – completely hijacking an organization to create the false impression of grassroots support.

What’s more, while Douglas says in 1958 that he did accept the Social Credit endorsement, Shackleton says he didn’t – and that is what saved him from being removed as a candidate.

“Douglas never acknowledged the endorsation, and this saved his skin when George Williams got the provincial Farmer-Labour executive to agree to disown any candidates who had entered into an alliance with the monetary reformers from the next province. One CF candidate, Jacob Benson, nominated in Yorkton, lost his Farmer-Labour credentials for this reason. Williams, hearing of the Weyburn situation, wanted M. J. Coldwell as provincial president to issue a statement also repudiating Douglas. Coldwell refused to do so.”

Douglas won by less than 300 votes and went to Ottawa. Later, as he mentioned, he blamed George Williams for the 1938 election loss– the CCFer who wanted Douglas fired as a candidate for taking a Social Credit endorsement. The Social Credit connection had deeper roots.

From “The Making of a Socialist”

The way I heard, while the meeting was called a Social Credit nominating meeting, there weren't any Social Crediters there and they nominated you as their candidate.

No, they didn't nominate me, they simply endorsed my nomination. Their resolution said that since they were not running a candidate, they would endorse my nomination and call on the people of the constituency to support me.

From that time on there was quite a lot of perturbation among the C.C.F. hierarchy, because at least one newspaper reported that you were in serious trouble from your ties with the Social Credit party. I presume they didn't know the story at all.

That's right, they didn't know the story. In those days we had no central organization. Every candidate ran on his own. We had little or no money for organizers or expense money to call candidates in to candidate schools. So, it was a matter of every man for himself, and Mr. George Williams, who at that time was leader of the opposition in the Saskatchewan Legislature, became very much perturbed about these reports that I was running as a C.C.F.-Social Credit candidate, and at one time he wanted the executive to expel me.

Mr. Coldwell, who was still provincial president and provincial leader of the C.C.F., would have no part of it until he heard my side of the story. When the election was over, and I laid all the facts before them, the copies of the resolution, and the other data, the whole matter was dropped.

That's haunted you, though, hasn't it?

Oh, yes.

I suppose that many people in Saskatchewan never really got the true story.

I'm sure most of them didn't know it.”

Of all the things that Douglas said, the idea that he’s sure that “many people in Saskatchewan never really got the true story” brims with irony.

In fact, there’s a third account, in Building the New Society:

“What followed was a piece of political sleight of hand worthy of Watergate, not illegal but far from proper. It got Tommy into a world of trouble - but also may have been the final trick that got him elected.

The way Tommy, campaign manager Ted Stinson, and Dan Grant saw it, even if a real Social Credit candidate didn't emerge, the Liberals might put up a phony one. Either way, the CCF would lose votes.

In early September, Stinson met with an Aberhart lieutenant in Moose Jaw and won an agreement that the new Alberta premier would endorse Tommy if he could win local Social Credit support…

Tommy's first move was to issue a statement, echoing the one from Coldwell and Williams but going a bit further: if he was elected, he told The Weyburn Review, he was "prepared to initiate and support legislation... which would make possible the Social Credit system being operated in any province caring to do so."

As mentioned above, all of this got Douglas in trouble.

… Williams and the others wanted him out, but the doctor persuaded them to hear first from Coldwell, who hadn't been able to make it to the meeting. The next day, Coldwell threatened to resign if Tommy was disciplined. Ejecting the Weyburn candidate "would have regrettable repercussions for the whole movement," he argued.”

The links between Douglas and Social Credit did not end with Douglas getting elected MP in 1935. Shackleton notes that Douglas’ saw Social Credit as potential allies, even when some considered it to be fascist.

“The confusion over Social Credit as a kindred or a hostile doctrine lingered for a few years - probably until John Blackmore began antisemitic barrages in the name of Social Credit. In the beginning, several Alberta CCF members including William Irvine had been instrumental in bringing Major Douglas, head of Social Credit in England, to speak in Canada. Monetary reform was a strong mutual concern. But Woodsworth denounced Social Credit as one more capitalist party and Coldwell, at least at a later date, saw fascist elements in it. Douglas took a softer approach.

In a letter to Coldwell in 1936 he said:

‘I cannot altogether agree with your expressed strategy in dealing with the Social Credit forces. My experience throughout this province is that while there is a general admission that Aberhart is bound to fail, there is a feeling on the part of those who supported him that they want some place to go. The last place they are likely to go is to the people who have held them up to ridicule .. when those who have supported Social Credit come to realize its inherent weakness they will find a more comfortable home in the ranks of the CCF.’”

Douglas’ prediction of the collapse of the Social Credit Party took a lot longer than he might have expected. The Social Credit Party in Alberta stayed in power for 36 consecutive years, until 1971, one of the longest unbroken runs in government at the provincial level in Canada. It was replaced by Progressive Conservatives.

Old Myths Die Hard: Prairie Giant

In the 2000s, CBC created a mini-series, called “Prairie Giant,” a biopic that portrayed Douglas arriving in Saskatchewan and taking the fight to Liberals. It received $600,000 from the NDP government of Saskatchewan for that province’s centenary, and NDP Premier Lorne Calvert was a creative advisor.

The story seeks to create a “David vs Goliath” rivalry where the Douglas and his CCF underdogs are going up against the villains, who are not Conservatives, but Liberals.

When it aired, some in Saskatchewan – (even Saskatchewan Party Leader Brad Wall) were shocked by its depiction of Liberal Jimmy Gardiner.

It essentially portrayed Gardiner as a gangster, drinking liquor in pool halls surrounded by goons – even though, as mentioned above, the real man was a teetotaler and a founding member of the United Church.

The CBC film took a historical incident - the shooting of striking workers near Estevan in 1931 under the Conservative government – and blamed it on Gardiner and the Liberal government instead.

The film portrayed Gardiner as Premier, supporting and justifying shooting strikers in a province-wide radio address. The speech attacks the strikers as immigrants and communists. This scene is an outright lie – not only was there no such speech and no such radio address, Gardiner wasn’t the Premier at the time, and he defending immigrants when Douglas’ political allies attacked them.

The theme of Liberals as villains is the throughline. When Douglas runs in 1935 against a Liberal MP, E.J. Young. Young is shown as delivering 1950s-style Red Scare anti-communist speeches, as if he is running for re-election for government, when he is running to defeat the Conservative government of the day, being led by R. B. Bennett.

Consider that in this film, that Jimmy Gardiner, who in real life fought the Ku Klux Klan, defended minority language and education rights, Jews, Polish, Ukrainian and French Catholics, is the bad guys. Gardiner is portrayed as a rich mob boss, when the real man was a teacher who grew up on a farm.

Whose point of view are we watching this movie from?

The one historical character who campaigned against the Ku Klux Klan and opposed eugenics is the bad guy.

The good guys in this movie are the people who were pro-eugenics and who got elected because they worked together with the KKK and eugenicists, and far-right politicians to beat Liberals – not Conservatives.

In the final analysis, Walter Stewart’s assessment of Douglas is revealing:

“Douglas is a curious combination of the austere and the amiable.

He's cool, resilient, shrewd; he has no friends outside politics and few within. He has erected such a barrier between himself and the world that no one I talked to - and I have talked to dozens of the people who know him best - has been able to penetrate it. Perhaps the most curious aspect of his personality is his inner reserve.

Despite his public reputation, he is not a firebrand, this careful, ascetic man. When he shows emotion - and he often does, as his speeches rise to crescendo on the wings of poetry or the Bible – it is emotion superbly controlled and used. Even his humour is a tool, rather than a quality of the man.”

Forced Forgetting: The Selective Outrage of Canadian History

The perception of political parties in Canada is untethered from the reality of their records, because so much of our history, politics, debates, and the media’s coverage of all of it is has been shaped by propaganda. It is about the spin and counterspin of how politicians and the powerful want themselves to be perceived, or how their opponents want to frame them.

People do not just make decisions based on logical arguments and debate. They make decisions based on deeply irrational beliefs that may define who they are as human beings, across the spectrum of human emotions – anger, disgust, fear, love, hope, anxiety.

If there a defining flavour to the propaganda of the CCF and the NDP, it is that they – and they alone – are standing up for working people and the downtrodden. This serves as both a sword and a shield. They attack their opponents as uncaring, and the fact that they do so must mean that, given their values, they could not and would not tolerate, much less embrace racist, eugenicist and right-wing economic views as other parties – even as they do.

Orwell’s Animal Farm was a bitter satire of this – spoiler alert – the revolutionaries end up being just as bad as the people they replaced – or even worse. When our politics becomes untethered from reality, they are not just fanciful, they are dangerous, because we are no longer talking about a shared reality, but about who is the better manipulator – who has the more convincing or moving or comforting argument. The story that makes them feel better, or more certain, more heroic, or more secure, or that motivates people through sheer terror.

In this world, it is no surprise that people would prefer to feel just a bit more satisfaction, or comfort, or security. It may be deeply satisfying and grounding to have the certainty that comes with total righteousness, that you are pure good; and that others are not just wrong, but pure evil. It drives out uncertainty – anxiety, fear.

It also comes with a terrible cost – because while it promises comfort and security, it means that the end will justify the means.

This has a huge impact on our ability to accept change, or that we have made a mistake. Because when people are duped, or scammed, people often blame the person for not being on guard. If the person deemed to be at fault and to blame is the victim, because of a judgment that they are weak, or weak in character, and they weren’t strong enough to stand up for themselves then that is a problem. Whose side are we on here? This the scammer’s point of view.

This notion of “weakness and strength” – of people’s authority – applies not just to the power and control that people can exert, but to whether they are to believed and paid attention to. Credibility accrues to power.

The sad reality of political manipulation, and that is that people may be taken in, not because they are greedy, but because they are generous; not because they are foolish, but because they are trusting and assume the best in other people.

Talented propagandists will manipulate people who are nice, kind, intelligent, by telling them things that are nice, empowering, reassuring, and wrong. Conmen may also exploit what is best in us - sympathy, kindness, and trust, a sense of duty and a commitment to helping others. By exploiting the very things we need to keep each other safe and to care for each other. And so, we all have reason to be a bit skeptical of others. It’s why trust is hard to build and easy to break. But we also have to check ourselves to ensure that our ideas are grounded in reality.

None of us is all-powerful. All of us have doubts. Every single human being needs to get permission to do something from someone else. So, we can all identify with an underdog. But what has happened in the telling of Canadian political history is that the good feeling of propaganda that exists entirely in its own fictional world, can take several forms. It doesn’t describe reality – it’s a worldview that is coherent and hangs together in the person’s head, but not out there in the real world. It can be a distortion, and it can also be a projection – where an accuser is guilty of all the accusations they are making, and everything is the complete opposite of the truth because they cannot bring themselves to accept the harms of the past.

History matters, and so does justice. Either we’re going to try to be honest and fair and evenhanded in talking about history – including our political biases - or we’re not.

If we can’t accept the documented facts around what happened 80 or 90 years ago – of people who are long dead - what hope do we have of achieving justice for the living in the present day?

The corruption of justice is that we do forgive some, and punish others, in ways that are totally unjust. We forgive powerful people and punish the weak when we need to be doing the opposite. This matters because of the country Canada actually is, and the country we think it is – and what really happened, and why we don’t know this history.

Because it takes real effort to have someone be chosen “The Greatest Canadian” while keeping the fact under wraps that he was elected with the help of Western Canadian Organizer for the KKK - that takes real, sustained effort too.