The History of Hyperinflation in Germany after WWI is Dangerously Wrong. Here's Why That Matters.

TL; DR: The inflation was caused by letting private banks print their own money. And extremism came after years of austerity, not inflation.

Many economists, historians and news articles will seek to explain the dangers of hyperinflation by citing Germany, but the history is almost entirely wrong.

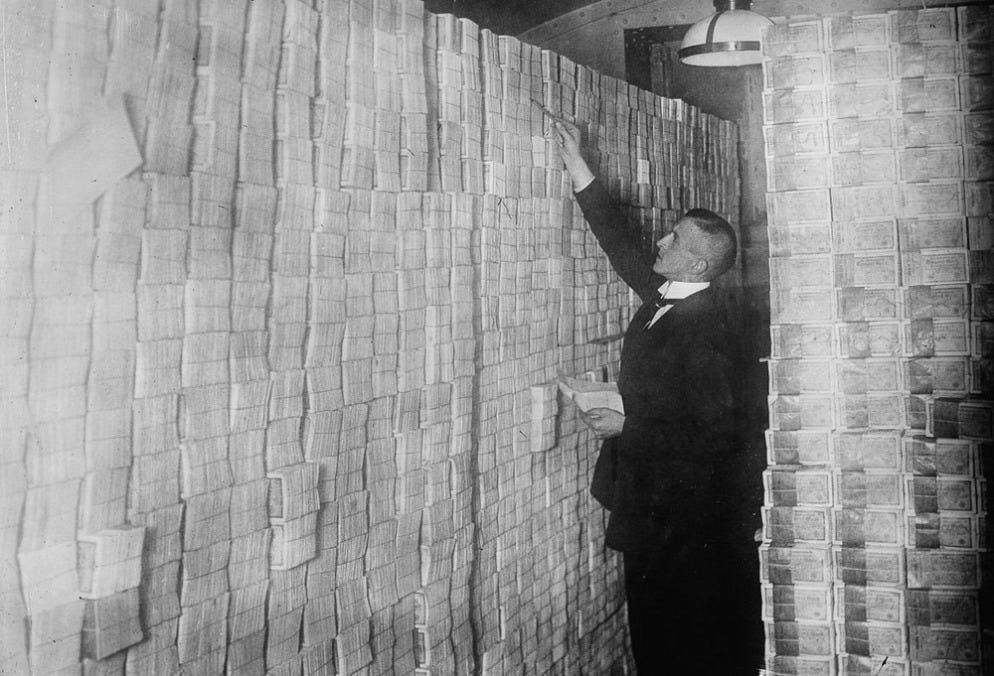

In the mid-1920s, there was a period of hyperinflation in Germany when the value of money dropped so badly that people were wheeling money around in wheelbarrows or used it as wallpaper (all true).

It’s also known that Hitler and the Nazis came to power sometime after this - and people make the mistaken conclusion that hyperinflation led to the rise of fascism and the Second World War. This is totally inaccurate history and is sometimes used as a reason to warn of the dangers of inflation. (Keynes also warned of the dangers of inflation in his “Economic Consequences of the Peace”).

This matters for many reasons, and the real story is worth repeating, to get the order of events straight.

In the 1920s, Germany was faced with massive debts to France and Belgium, to pay war reparations.

“According to French and British wishes, Germany was subjected to strict punitive measures under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. The new German government was required to surrender approximately 10 percent of its prewar territory in Europe and all of its overseas possessions. The harbor city of Danzig (now Gdansk) and the coal-rich Saarland were placed under the administration of the League of Nations, and France was allowed to exploit the economic resources of the Saarland until 1935. The German Army and Navy were limited in size. Kaiser Wilhelm II and a number of other high-ranking German officials were to be tried as war criminals.

Under the terms of Article 231 of the treaty, the Germans accepted responsibility for the war and, as such, were liable to pay financial reparations to the Allies, though the actual amount would be determined by an Inter-Allied Commission that would present its findings in 1921 (the amount they determined was 132 billion gold Reichsmarks, or $32 billion, which came on top of an initial $5 billion payment demanded by the treaty).”

The hyperinflation in Germany is one of the best known such episodes in history. To give an indication of the level of inflation, a loaf of bread that cost 160 marks at the end of 1922 cost 200,000,000,000 (200 billion) marks a year later.

Many economists, historians and news articles will seek to explain the dangers of hyperinflation by citing the German government, but the history is almost entirely wrong.

The Nazis did not come to power until more than half a decade after the hyperinflation had come to an end. The explosion in money-printing in Germany in 1922 and 1923 was not by the government at all.

A clearer story had been produced in a working paper of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[6] It was, in fact, a consequence of a policy blunder by the Allies, who insisted that the government be stripped of its role in supervising or running the central bank:

“The Reichsbank president at the time, Hjalmar Schacht, put the record straight on the real causes of that episode in Schacht (1967).

Specifically, in May 1922 the Allies insisted on granting total private control over the Reichsbank. This private institution then allowed private banks to issue massive amounts of currency, until half the money in circulation was private bank money that the Reichsbank readily exchanged for Reichsmarks on demand. The private Reichsbank also enabled speculators to short-sell the currency, which was already under severe pressure due to the transfer problem of the reparations payments pointed out by Keynes (1929). It did so by granting lavish Reichsmark loans to speculators on demand, which they could exchange for foreign currency when forward sales of Reichsmarks matured. When Schacht was appointed, in late 1923, he stopped converting private monies to Reichsmark on demand, he stopped granting Reichsmark loans on demand, and furthermore he made the new Rentenmark non-convertible against foreign currencies. The result was that speculators were crushed and the hyperinflation was stopped. Further support for the currency came from the Dawes plan that significantly reduced unrealistically high reparations payments…. this episode can therefore clearly not be blamed on excessive money printing by a government-run central bank, but rather on a combination of excessive reparations claims and of massive money creation by private speculators, aided and abetted by a private central bank.”

So, it was not the German government that was responsible for hyperinflation at all. It was the private central bank, which allowed private banks to print their own currency – to offer credit that was convertible into government marks on demand. Effectively, it gave private banks a license to print money, and they did.

This period is routinely used as a scare story about the dangers of central bank money printing, or government attempts to stimulate the economy, when it was neither.

Hyperinflation is caused by a country having to pay off debts in another country’s currency. This is the reason for every instance of hyperinflation, except one - Zimbabwe, which also had special circumstances. If there is an economic downturn - and there is a change in the exchange rate, it can trigger a downward spiral. There is no evidence that printing money for domestic use causes uncontrolled inflation - it is always printing money associated with paying off foreign debts. This is what happened to Venezuela.

The hyperinflation in Germany stopped when they introduced a new currency, in November 1923. It was a period of serious economic disruption - but it is not what led to the rise of fascism. Hitler did not come to power in 1923. In the German elections of 1924, the Nazi party only received 3% of the vote.

After the hyperinflation, until 1929, Germany had the fastest-growing economy in the world. That growth ended in 1929, with the Wall Street Crash and financial crisis that started the Depression. The top five economies around the world were all shrinking, and for the first years, they all pursued cuts and austerity.

As Mark Blyth has argued at length in his outstanding book, “Austerity: History of a Dangerous Idea” - is that it doesn’t work, and results in very nasty politics.

After 1929, in Germany, conservatives and social democrats alike pursued austerity.

After 1929, in Germany, conservatives and social democrats alike pursued austerity. The Nazis stayed a fringe party over several elections, with their vote growing as economy sputtered and suffering got worse, until they were elected in 1933 on a promise of jobs. Hitler and the Nazis did get the economy running again, mostly by building up the military.

In the 1930s, France might have been able to put a check on Germany’s expansion by also investing in a military build up. They opted for cuts and austerity instead, and were in no position to offer any meaningful resistance to a German invasion.

In Japan, the major target for budget cuts was the military. Over the 1920s, the military’s share of the government budget was cut in half. After a number of years, and continued cuts, the response from the military was increased radicalization and outright assassinations. A number of senior officials were assassinated by the military, including two Prime Ministers.

In late 1931, an army plot to overthrow the government was uncovered - which was related to the years of cuts. “A decade of austerity had convinced the Japanese military that they were ‘at war with the entire civilian political elite.’” A number of other officials were murdered in a failed coup in 1936, but the die was cast, and spending opened up for the Japanese military and war on China in 1937.

Austerity means stripping people of money - and stripping them of control and leaving them powerless. The assumption is that the economy will just recover its balance - and come back to equilibrium on its own. It won’t. As people fight over scarce resources, it leads to conflict and the splintering of societies, along any number of tribal and tribal nationalist lines.

It wasn’t hyperinflation that led to the Nazis. It was austerity. It was austerity that led to the extreme nationalism and militarism of Japan. These were the two major axis powers in the Second World War, who pursued empires through invasion and conquest as a means to build wealth.

As FDR put it, “People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.”

Keynes quit the Versailles Peace talks of 1919 warning that the consequences of the peace - the reparations demanded of Germany - would result in a war in 20 years. He was right, right down to the year.

That is why, after the Second World War, the solution was to do the opposite, and launch a Marshal Plan that would rebuild Europe, including a plan that in 1948 that introduced the Deutschmark reset the entire German economy.

“The Deutsche Mark replaces the Reichsmark in the three western zones. The Deutsche Mark banknotes had already been printed in the United States at the end of 1947 and then brought to Frankfurt as part of the secret “Operation Bird Dog”.

The banknotes are distributed as of Sunday, 20 June. In exchange for 60 Reichsmark, every citizen of the western zones receives 40 Deutsche Mark directly from the ration offices, followed by a further 20 Deutsche Mark in a second tranche shortly thereafter. As of 21 June, the Deutsche Mark is the sole legal tender. Everyday payments such as wages, salaries, insurance and rents are converted at a rate of 1:1. However, those with savings are hit hard: Reichsmark balances are gradually converted to Deutsche Mark at a rate of less than 1:10.”

Well done!! There is a lot of misinformation about this era, and you have set the record straight!