The National Interest, Part 1: the Carbon Tax, Inflation & Climate Change Policy in Canada

The math is clear: the carbon tax is not the cause of people's economic misery. We need real investments that answer the real concerns of Canadians.

There’s lots of screaming right now about Canada’s carbon tax, which is being singled out for causing all sorts of terrible economic problems.

I am not going to defend or promote the carbon tax. I do want to explain it, because the current debate in Canada is so divorced from reality.

We are currently locked in a repeating loop of people talking at cross purposes.

We have people who are saying that the carbon tax is to blame for economic pain, and people who are responding that the carbon tax cannot be to blame. We don’t get to the further questions of why people are really hurting, or how to solve it.

While Liberals may want to see the economy as better than it is, we don’t live in a government run-economy: we live in a mixed market economy, and it’s prices in the market that are hurting everyone. There is no doubt the Conservatives are trying to pin the blame on the Federal Liberal Government, and certainly because the Conservatives don’t want to acknowledge that they are basically repeating oil industry messaging.

The changes in private prices and oil profits that oil companies have been taking out of the economy are far more dramatic than the changes in tax revenue by government

It’s the oil companies making record profits and who have been able to charge higher prices even when their Canadian production costs remain the same.

High gas prices are at least one significant driver of inflation. In last years, they have been on a roller coaster ride. At the beginning of the pandemic, in March 2020, the price of oil per liter in Ontario dropped to $0.74/l, but by summer of 2022 had tripled, to $2.11/l.

That directly contributed to the price of inflation - and the increase was by over $1.00 a litre - many multiples of the carbon tax.

As this article from February 2023 shows, 2022 was the most profitable year in the history of Canada’s oilpatch.

“There are many ways the sector could spend those hefty returns, but so far companies seem unwilling to waver from their primary strategy of paying down debt and passing on a good chunk of those profits to shareholders.”

It’s important to note what happened here: these profits, were the result of high oil prices pushed up by the Russian invasion of Ukraine - with no actual increase in Canadian production costs.

Companies could have used those profits to expand production - new spending, more jobs - but the money went to making shareholders and bondholders richer. Because more production would cause the price to drop.

So, the debate gets stuck on whether or not the carbon tax is the problem, when it needs to be about “what is actually causing people’s economic pain and what do we need to do about it?”

Because we do need to recognize that there is a lot of economic pain out there.

Lots of Canadians families and businesses are at or near the breaking point. It’s not just from policies of the last four years, or the past eight. As I have written, we are dealing with more than two decades worth of bad monetary policy from central banks and over four decades of bad macroeconomic policy generally.

Canadians have been persuaded that it is federal government’s deficit, or spending, or the carbon tax that is responsible for the problems in the economy, like inflation.

It’s basically mathematically impossible for the carbon tax to be the single thing that’s causing this suffering. The numbers just aren’t there.

This matters. The fact that we’re spending so much time focused on the carbon tax means we’re not talking about all the real causes of inflation.

Scrapping the carbon tax is not going to fix anything - and it is also the opposite of being fiscally responsible.

It is completely insane to be going into debt to borrow and spend billions of dollars subsidizing the price of a product you buy once and you burn.

If this shows anything, it shows just how overreliant we are on a single type of energy, because when there is a crisis, and they can hike the price as high as they want, and they have us over a barrel.

So, if we’re going to go into billions of dollars more debt, let’s make sure it’s going towards helping people, right now, to lower their long-term costs. Lots of people want to be able to save energy and save money but they can’t afford to. This is also true of municipal governments, and Indigenous governments, as well as individuals. So spend money on that, and provide people with income supplements, but let’s keep working on alternatives, because this is not going to get better.

From a government’s point of view cutting fuel taxes, it is not fiscally reponsible, or fiscally conservative: it is fiscally delusional. Canadian governments scrapping fuel taxes while running budget deficits means we are investing in reinforcing the status quo, instead of in diversifying away from an energy source on which we are too dependent.

There’s been no strong pushback against the Conservative claims about the carbon tax and inflation - the left in Canada hasn’t been particularly critical of oil and gas companies either.

We also need real investments that answer the real concerns of Canadians - not just in new fuel but in new technology and infrastructure to make the cost of living and doing business more efficient and therefore more affordable.

It is not going to happen on its own, and reliance on the carbon tax alone is not going to be enough. We need is a sustained effort to reduce people’s costs and help them switch - in energy efficiency investments, in new building codes, in designing cities and infrastructure.

We’re not asking the relevant question, which is if it’s not the carbon tax, what the hell is making everything so expensive?

Now, I really don’t care about the politics or personalities. I just can’t stand the relentless lies about all of it.

First, I’ll talk about

Climate change, the carbon tax & why provinces don’t act in the national interest

Tomorrow Country: Booms and Busts in the Canadian Prairies

Norway, Alberta, Saskatchewan and the crash of 2014

Petro-Politics & Petro-Propaganda in Canada

Finance and Debt: the Economics of the Rest of It

What we actually need to do.

We’ve been talking about Climate Change for a Long time

I remember first hearing about climate change in the 1980s. I was such a nerd it didn’t occur to me that watching NOVA on PBS and reading the science section of my dad’s subscription to The Economist was anything out of the ordinary. How was I to know? Isn’t that what all 15 year old boys did?

The 1980s, was an era of many existential concerns, and climate change was one of them. I am not a fan of the PC government of Brian Mulroney, however they did succeed in obtaining agreements with the U.S. in the 1980s to reduce acid rain, by requiring industries to reduce their emissions of certain chemicals. The reduction of CFCs was also effective in reducing harm to the atmosphere from the degrading the ozone layer. It was regulation, and it worked.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, there was broad political and public consensus about the reality of climate change and the need for a significant change to deal with emissions wasn’t a matter of debate. The so-called “Kyoto Protocol” was signed in 1992, 32 years ago. Kyoto was never implemented, and now provincial governments are pleading with the federal government to scrap or modify the “carbon tax”.

There is no question that,

“Since 1751 the world has emitted over 1.5 trillion tonnes of CO2.”. That comes from burning 486-billion tons of carbon fuel - with the carbon combining with a trillion tons of oxygen. That extra CO2 makes the atmosphere better at holding in heat, like a blanket, but it’s also being absorbed into the ocean and making it more acidic.

To try to put this in perspective, Mount Everest weighs around 350 trillion pounds or 175,000,000,000 tons. Since 1750, we have burned a quantity of fuel equal to two and three quarter Mount Everests in size. That’s just the fuel - the CO2 smoke created as the fuel reacts with the oxygen in the air is much larger - more like eight Mount Everests.

And while CO2 is what plants pull out of the atmosphere as food, we’re still cutting down the wilderness faster than it has a chance to recover, and that means die-offs for lack of habitat and food.

It’s not made up, it’s not a plot, it’s not socialism, it’s not anti-religion, or pro-religion. It just says that human beings have burned a lot of fuel in order to build the world we all live in today, and it has added enough CO2 smoke to the atmosphere so that the atmosphere is holding in the heat more.

The reason this makes a big difference for climate is that as the temperature goes up, the more water and moisture the air can hold. This is obvious - in cold winters, the air is very dry, whereas humidity is associated with warmth.

That is a twentyfold difference. If the atmosphere is warmer, it means it can hold more water, as well as more energy, for violent and damaging storms with higher winds, as well as flash-flooding from rain. Predictions by scientists decades ago of how climate would change would unfold have been validated.

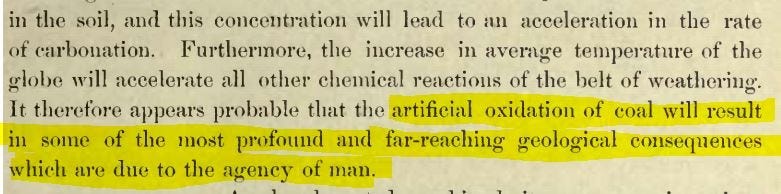

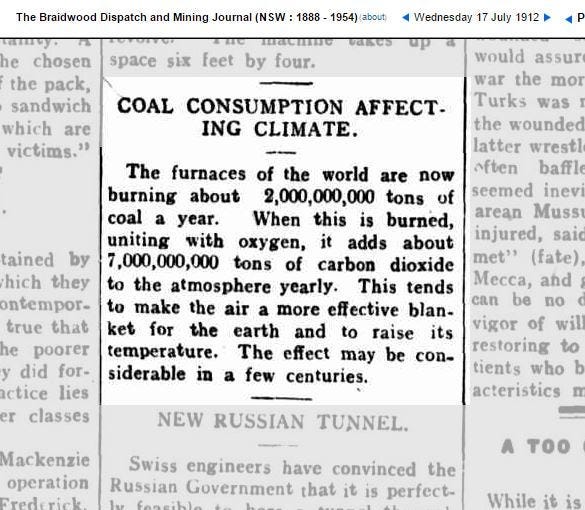

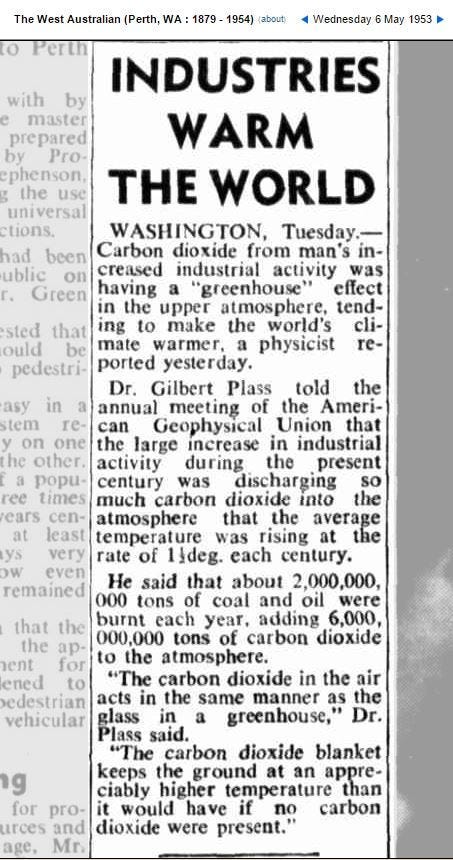

There is a great article - “We’ve Been Talking about Climate Change for a Long Time” by Cameron Muir that points out that 120 years ago, the effects were recognized and predicted. The “artificial oxidation of coal” - human beings burning it - :will result in some of the most profound and far-reaching geological consequences which are due to the agency of man.”

1904:

1912:

1953:

It’s also the case that Exxon - the oil giant - knew, from their own research, that burning all that fuel was thickening up the atmosphere and making it better at holding in heat, leading to long stretches of changing weather, including more intense weather.

“In the first place, there is general scientific agreement that the most likely manner in which mankind is influencing the global climate is through carbon dioxide release from the burning of fossil fuels,” Black told Exxon’s Management Committee, according to a written version he recorded later.

It was July 1977 when Exxon’s leaders received this blunt assessment, well before most of the world had heard of the looming climate crisis.

So, there really is no arguing about this. The facts are clear, the evidence is in, it is settled. The question is what we do to make it better, and making sure we are doing everything we can to make the transition work, and make it pleasant instead of painful.

The carbon tax & climate change policies of the past

One of the things that people don’t realize about the carbon tax is that it was created as the conservative, right-wing, business-friendly, free-market, keep-government-out-of-it solution to climate change.

Why do it this way? So that the market will respond and innovate on its own!

The Tax Policy Centre breaks it down here:

Q. What is a carbon tax?

A. Emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are changing the climate. A carbon tax puts a price on those emissions, encouraging people, businesses, and governments to produce less of them. A carbon tax’s burden would fall most heavily on energy-intensive industries and lower-income households. (emphasis mine) Policymakers could use the resulting revenue to offset those impacts, lower individual and corporate taxes, reduce the budget deficit, invest in clean energy and climate adaptation, or for other uses.

One of the basic justifications for the tax is that oil companies are selling a product that has real costs environmental and therefore economic costs:

… Energy prices do not currently reflect these costs of greenhouse gas emissions. Those who benefit from burning fossil fuels generally do not pay for the environmental damage the emissions cause. Instead, this cost is borne by people around the world, including future generations. Imposing a carbon tax can help to correct this externality by raising the price of energy consumption to reflect its social cost.

Estimates of the environmental cost of carbon emissions are sensitive to scientific and economic assumptions and thus differ greatly. Early in the Biden Administration, the US Interagency Working Group on Social Costs of Greenhouse Gases (2021) estimated that, by one measure, the social cost of carbon was about $50 per metric ton in 2020. Under other assumptions, however, the value could be as low as $14 or more than $150. In 2022, however, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed a cost of $190 per metric ton. At the time of writing, that proposal was still subject to review. By contrast, current US charges on fossil fuels--chiefly the federal excises on automotive fuels--amount to only about $5 per ton (IMF 2019).

Various independent studies of the carbon tax in Canada show that with its rebates, it returns more to 40% of Canadians who need it the most than they are paying, including the Parliamentary Budget Officer.

A couple of points here. People may ask, “how can it possibly be any use if you’re rebating money to people?” and the answer is fairly obvious, look at the way people are changing their behaviour right now around the carbon tax.

A couple more points about why carbon tax is not causing inflation, is that inflation is soaring around the world, not just in Canada.

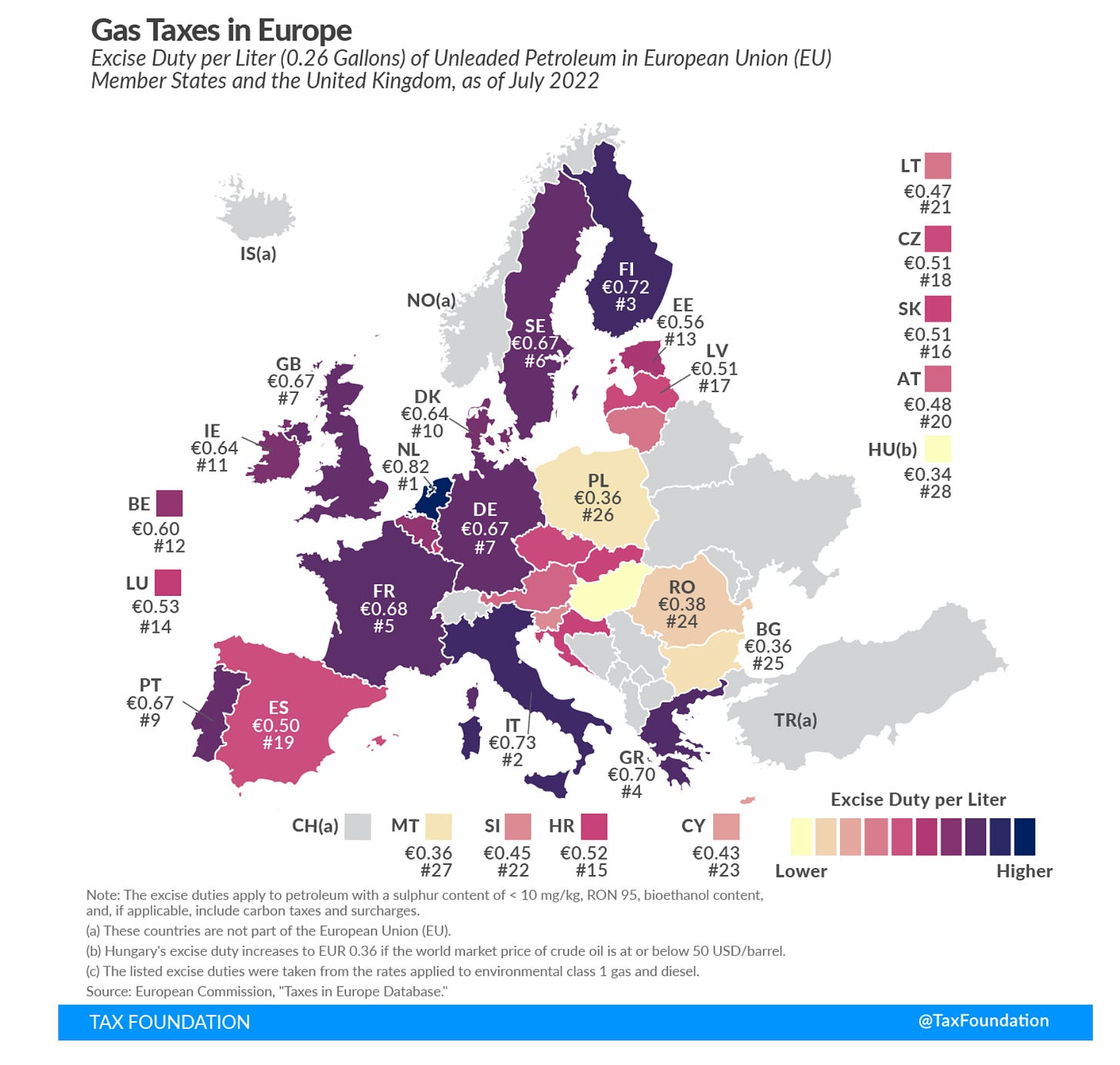

The other is that there are countries around the world, including oil-rich Norway, which have higher taxes per litre for decades, in part because they don’t want people to waste a resource that is limited, valuable and useful.

These European taxes on energy have been high for decades. Inflation is not being caused by taxes.

Is inflation caused by gas taxes? No. Is inflation caused by private companies putting up the price of oil and gas? Absolutely - and taxes are not the only things in a private company’s budget. They also have profits, and debt, and options, and bonuses and executive salaries, and tax breaks for entertainment like luxury boxes at pro sports games.

So let’s talk about a foundational problem.

Provinces don’t act in the national interest. And they have jurisdiction for natural resources.

When you consider the most basic debates about politics and the economy, some of the arguments about whether decisions and projects are best made by a government (national or sub-national) or the private sector.

There are arguments about who has the most expertise, who is qualified, who knows best, and who has the best access to information. This is sometimes justified by arguing “what does someone in government know,” about such and such a subject, usually running a business.

This misses the key question, which is, “whose interest do they serve?” The question is sometimes phrased as Cui Bono? and supposedly dates back to the Roman statesman Cicero.

That sometimes comes across as “Who benefits?” and can have deeply negative implications, because it can suggest corruption, favouritism or that people are acting out purely out of monetary self-interest or greed.

This is simply acknowledging that different sectors have different constituencies, but whose interest they are acting in matters.

It is self-evident, by legal definition that the private sector has private interests.

Provincial and state governments have provincial and state interests.

Only national governments are responsible for the national interest, for every citizen.

It has to be said, that while there may be areas of overlapping interest, where the private sector and sub-national governments are aligned with the national government, they are not a replacement for the national government, which is the only entity that has a responsibility to keep the interests of everyone in mind.

Of course, people will point out all the ways in which governments fail to meet that responsibility or act unjustly, which still doesn’t change the fact that no other entity than the federal government is responsible for the National interest, and for the overall public interest.

The political, legal and economic reality is that if the Federal government does not stand for the public interest no one will. This is the case for every level of government: If officials fail in their obligation to serve, there is often nowhere else to turn, because no other entity has the power and responsibility.

This is the problem with downloading everything to sub-national governments, as well as expecting the private sector can fill in, in providing public services. They do not act in the national interest: they work in their own, more narrow interest.

It has to be recognized that it is possible for the government of one province to sanction actions that can harm people in another province. An obvious, and realistic example would be cities spilling sewage into rivers and streams and sending their pollution downstream to people in other provinces, and it’s killing the lake where it all drains to. This is what is happening to Lake Winnipeg, in Manitoba, which is one of the largest freshwater lakes in the world.

You need someone who can settle the dispute, and that’s the federal government and federal courts. Because there has to be someone who is considering the national interest, because part of being a nation is the understanding that we’re going to live with the same rights and laws that apply to everyone, because that’s a way of keeping the peace. That’s the fundamental premise and promise of democracy and the rule of law.

Is the people of one province do something that is against the national interest or that harms people from another province, there needs to be ways of debating the issue and resolving it without recourse to breaking the law.

We need to recognize that there is such a thing as the national interest, whatever country we live in, and that there is a reason some areas of jurisdiction should be federal, and not provincial. You need some limits on provincial powers.

In Canada’s constitution, provincial governments were been awarded extraordinary powers over many of the most important public programs - including health, education, human rights - the list goes on - and it includes natural resources and the environment.

Unless a project crosses over two provinces, the federal government tends not to be involved. Provincial governments have the say on forestry, mines, oil wells, pipelines within their provinces, and the oil and natural gas tends to be in Western Provinces - British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan. Manitoba has its own oil patch, and there is some oil offshore the Eastern Provinces, Newfoundland and Labrador being an example.

Canada’s oil reserves are colossal - third place in the world after Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. The challenge for Canada is the oil is not as cheap to process or access, as this chart shows, (though it is from 2015).

Canada’s costs per barrel in 2015 was $41 per barrel.

Both the type of oil being used as well as access to distribution make a big difference.“Alberta has 39% of Canada's remaining conventional oil reserves, offshore Newfoundland 28% and Saskatchewan 27%, but if oil sands are included, Alberta's share is over 98%”

What should be obvious from this map is that the heavy concentrations of oil deposits, especially in the Western Provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan - are landlocked by the Rocky Mountains, Canada’s Northern Territories and the American West. Not only are they thousands of kilometres away from their customers by land, they have no access to ports.

So the oil has to be shipped through thousands of kilometres of pipelines, or by rail, either to get to refinery or to port, it must pass through another jurisdiction. This is a geological and geographic reality that can’t be overcome - not a political one.

I appreciate the Pogo reference.