The National Interest, Part 2: Tomorrow Country: Booms and Busts in the Canadian Prairies

The oil price crash of 2014 had a devastating impact we're not close to recognizing

This graphic, from the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, (CAPP) tells several different and important stories about Canada’s economy over the last 70 years - including explaining our politics right up to this moment.

For example: people are wringing their hands about Capital investment dropping, along with Canadian productivity. The chart with grey and red bars explains why, and it has everything to do with the price of oil plunging in 2014.

Up until 2014, billions and billions of dollars in investment were pouring into Alberta because the price of oil was so high. Then the price of oil dropped, which suddenly made many of those projects unfeasible. As was widely reported, there was a risk that there could be tens of billions in stranded assets in Alberta’s oilsands.

That investment kept declining, because new projects still weren’t profitable, and they had massively overpaid for ones that hadn’t worked out.

That explains pretty much the bulk of changes in foreign investment, right there. The global price of oil fell - or, more accurately, was lowered.

When the price of oil is high, and so is Canada’s dollar. It’s great for one export - oil, which is priced in U.S. dollars.

The shifts in exchange rates make it hard for other exported products, especially manufactured ones, because the value of contracts with foreign buyers has suddenly changed. Either the buyer has to find more money to pay you in Canadian dollars, or you have to find a way to save on costs.

Whether or not it was just people believing their own PR, people were talking about Canada as an “Energy Superpower” and they thought it would go on forever. During that same time, Canada’s manufacturing industries were losing hundreds of thousands of jobs. Part of this was from Chinese competition, but the soaring Canadian dollar disrupted cross-border trade in auto manufacturing and made our exports more expensive. The global financial crisis only added to the mess.

This also has an effect on Canada’s productivity, because of the kinds of investments and decisions people and governments both make.

At the time, Alberta’s economy was growing faster than China’s, and the province was basically allowing for unlimited development. They took an overheating economy, and then poured fuel on it.

There is a simple reason why this failed, which is that when you are getting into a market that is too hot, and you are paying for an asset at the top of the market, because you thought the price of oil would never go down, when it does, you cannot service your debt - unless you raise your prices. Hence, inflation.

If interest rates are low, and the returns on oil are high, it might seem like sense to borrow to invest.

Because until the crash happens, the people who are selling at the top of the market are making a fortune, but the market really is too hot - and that means people are overpaying.

Up until 2014, the price of oil had been high for a number of years, over $100 a barrel. One major reason for this were the wars in Iraq and later in Syria (Canada, unlike the UK, did not join in the 2003 Iraq War.) At the time, there were predictions that the price of oil would be high forever, and would keep going up, and people believed them. One of the things that changed that trajectory was the fracking revolution. It made such a difference in freeing up oil and natural gas for production that for the first time in decades, under President Obama, the U.S. became a net exporter of energy.

In 2014, Saudi Arabia opened up production, and the price of oil dropped.

You can see just how wrong the government’s projections were - clinging to the hope of a massive increase in prices.

In the chart above, the red line is what the 2015 federal budget predicted - that the price of oil would surge from $55 to near $80. The blue line is the futures market for oil - from $55 to close to $70 a barrel, clear through to 2022.

By contrast, the actual price in January 2016 - just a few months after these projections - was $30 a barrel.

It was a repeat of what happened in the 1980s, when Albertans put these bumper stickers on their trucks: “Please God, let there be another oil boom, I promise not to piss it away the second time.”

Tomorrow Country: the prairies as a place of booms and busts

The Canadian oil industry only started to take off in Western Canada in the 1950s, and story of those booms and busts in capital are the story of economic and political turmoil.

The capital spending is what tells the real story of intense prosperity - especially in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as well as in the mid-2000s to 2014, when oil were prices were either going up, or staying up.

When that happens, the economy gets turbocharged, because aside from the billions flowing into the economy because of the oil you’re pumping and exporting, there’s all the billions going into expanding or creating the entire industrial, social and economic infrastructure - housing, roads, bridges, schools, office buildings, finance.

In this case, it was into areas that were high in oil - which are all landlocked, .

Western Canada has always had an intensely volatile economy. Even as it was being founded, it was being considered as a “colony” of “central Canada” - Ontario and Quebec, and the trade and investment ties reflected that.

People talk about Canada’s economy as being “hewers of wood and drawers of water” - which, notably, is based on a Biblical curse.

The prairie provinces have often been reliant on commodities whose prices first created great wealth, then destroyed it.

The first commodity was wheat, and it generated incredible wealth from producer to grain and rail barons.

As you can see from the chart below, which adjusts prices for inflation, the price of wheat at the farm gate which is 2017 was $5 a bushel, was between $20 and $30 a bushel from 1867 to about 1917.

Western Canada had just opened up, and new crops had been developed that could be harvested.

It’s also worth pointing out a critical factor in the development of “pioneer” agriculture in both the U.S. and Canada, which is that homesteaders often received land for free, so long as they improved the land.

It’s worth pointing out that this really was taking place in an age prior to the supremacy of oil, gas and the internal combustion engine.

Just as with oil, sustained high returns on commodity prices also drive investments in the real and social infrastructure required to sustain it, and it is also debt-financed.

When the Great Depression hit North America in late 1929, the consequences were disastrous for the farmers of the Midwest. After record harvests the previous year, and facing oversupply throughout most of the 1920s, demand all of a sudden dried up for most foodstuffs, while Europe imposed quotas and embargoes and Argentina and Australia swamped the markets with their exports. Another record grain crop in 1931 was harvested with little hope for its resale, domestically or as export. The price of Chicago wheat fell hard and fast from $1.40 per bushel in July 1929 to 49 cents – a fall in value of about two-thirds in just two years.

The Great Depression had its hardest impact in Western Canada.

During the Depression, Canada had one of the worst economic collapses of any country in the world, and in Western Canada it was worst of all. Provincial governments were teetering on the verge of default, and unemployment was at unimaginable levels: There was unemployment of up to 75% in some towns.

“The Great Depression wrought great economic hardship throughout the world, but few places suffered so sharp a decline in income or required so much government assistance to survive as the Canadian prairie provinces. From 1928 to 1932 Canada's agricultural economy declined 68 per cent while the Prairies ' declined 92 per cent. In Alberta the average per capita income in 1928-29 was $548 ; in 1933 it decreased by 61 per cent to $ 212. The Canadian average per capita decrease during the same period was 48 per cent.”

To repeat: in 1932, the agricultural economy of the Prairies was only 8% of what it had been just four years before. Then-Prime Minister R.B. Bennett, who was a Conservative from Calgary, Alberta, took a “laissez faire” approach for several years, none of which worked. He desperately ushered in a series of reforms, but it was too late.

After 1935, and the creation of the Bank of Canada, the government embarked on a series of other debt-relief and investment measures that lasted until the 1950s. Provincial governments were relieved of their Depression-era debts, farmers were able to write down 50% of their debts as well.

The Federal Government also created a number of modern “macroeconomic shock absorbers” - Federal Employment Insurance, as well as transfers and some equalization payments. These payments are generally explained as being necessary to ensure that all Canadians can receive certain services (health, welfare and education) and that provinces can provide them at a similar tax rate. There is a more important reason, which is that transfer payments are essential for any country that has multiple jurisdictions and a shared currency. There are costs and benefits that come with having a shared currency. Intense economic activity in one jurisdiction has impacts on the exchange rate, which affects the entire economy - exports, imports, local revenues.

Every functioning federation has these policies out of economic necessity: they prevent local collapse. The U.S. has them, Australia has them, Canada has them. The Eurozone did not have them, which caused the currency crisis there.

The next Commodity: Oil

The price of oil was relatively stable for many years, until the energy crisis of the 1970s. Much of the economic crisis of the 1970s was caused mostly by a massive shock to the price of oil, which went up from $2 a barrel to $30 a barrel almost overnight. This is understood: but the full impact of energy prices and their role in the economy may not be.

In 2011, James D. Hamilton of the University of California, San Diego wrote a paper that linked recessions to oil price shocks, especially post-WWII. The argument he makes is simple enough, and it is fairly clear that the price of oil played a role in “regular” recessions (the financial crises of 1929 and 2008 were different because they involved bank failures). A spike in the price of oil does more than just “crowd out” other purchases. Hamilton argues that even though the actual size of an increase in the price of oil might be limited, it has a much larger effect.

In addition to the higher cost of gasoline crowding out other purchases, people are likely to stop buying cars which leads to a recession in manufacturing.

But just as important, the price of energy — and especially oil — underpins the cost of most goods and trade at every step along the supply chain, from turning raw materials into materials that can be processed — whether wood, metal, or food — as well as the processing, manufacture, assembly, and distribution.

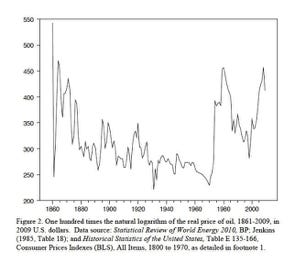

Hamilton’s chart in Fig 2. shows one hundred times the natural logarithm of the real price of oil.

Recessions happen just after oil prices go up, periods of growth happen when the cost of oil goes down. The exceptions are financial crises like the crashes of 1929 and 2008, though 2007-2008 oil seems to have played a role.

Hamilton writes:

“Key post-World-War-II oil shocks reviewed include the Suez Crisis of 1956-57, the OPEC oil embargo of 1973-1974, the Iranian revolution of 1978-1979, the Iran-Iraq War initiated in 1980, the first Persian Gulf War in 1990-91, and the oil price spike of 2007-2008.”

Hamilton details how shortages had a widespread economic impact far beyond simply having to spend more on oil. He cites an article in the New York Times that illustrates the impact of the 1956-57 Suez Canal crisis on Europe, which put access to two-thirds of Europe’s oil supply at risk:

“Dwindling gasoline supplies brought sharp cuts in motoring, reductions in work weeks and the threat of layoffs in automobile factories... There was no heat in some buildings; radiators were only tepid in others. Hotels closed off blocks of rooms to save fuel oil. . . . [T]he Netherlands, Switzerland, and Belgium have banned [Sunday driving]. Britain, Denmark, and France have imposed rationing... Nearly all British automobile manufacturers have reduced production and put their employees on a 4-day instead of a 5-day workweek. . . . Volvo, a leading Swedish car manufacturer, has cut production 30%.”

When we think of energy use, we may think generally of “power” but really it is three different applications: heat, light, and work. As Hamilton points out, in the 19th century oil was mostly used for illumination. When oil and gas were first harnessed, they were used either for light or warmth. The oil in lamps was much brighter than the stuff that was used before — whale oil.

But the real change in the application of energy to productivity — something people associate with machines, or “capital” alone, is that it is energy that drives a machine. An oil shock makes everything more expensive and reduces productivity at one stroke. Hamilton suggests that the economic damage caused by an oil shock may be an order of magnitude greater than increased cost of the oil on its own.

Industrial activity is more than just man and machine, it also requires the energy to run that machine. Oil is concentrated energy, and a machine concentrates that energy into work. In industrial manufacturing, every step of the process is energy intensive: it takes energy to make sand into glass, petroleum products into plastics, ore into metals. Those materials then require further energy to be worked into a final product, and further energy still to be transported to a customer. This means that the cost of energy eats into the cost of labour in a way that is far more damaging to the economy than you might expect.

“For example, the global production shortfall associated with the OPEC embargo averaged 2.3 mb/d [million barrels per day] over the 6 months following September 1973. Even at a price of $12/barrel, this only represents a market value of $5.1 billion spread over the entire world economy. By contrast, U.S. real GDP declined at a 2.5% annual rate between 1974:Q1 and 1975:Q1, which would represent about $38 billion annually in 1974 dollars for the U.S. alone. The dollar value of output lost in the recession exceeded the dollar value of the lost energy by an order of magnitude.”

In 1951, an oil shortage and a recession followed a strike by workers in Texas was severe enough that all Canadian civilian flights were suspended. Hamilton’s graph of oil prices shows the price of oil was steadily dropping until 1973. Then, after the Arab-Israeli conflict, the OPEC cartel hiked the price of oil from $2 to $30 a barrel. Strikes in Iran that spread to the oil sector reduced the global oil supply by 7%. Likewise, the economic "boom" of both the 80s and 90s occurred with low oil prices. In 1980, it seemed inconceivable that oil could drop again — but it did, to $10 a barrel.

This is important, not just for our understanding of oil and the economy. The assessments of economists, politicians and pundits and historians have focused on the economic policies of the governments of the day, not inflation and recession induced by oil price shocks.

The conventional wisdom is also that the 1970s economic problems were in part the result of "leftist" policies of the governments of the day: Labour in the UK, Trudeau Liberals in Canada, Jimmy Carter's Democrats. Even Nixon, a Republican introduced a number of policies that would be considered left of most Democrats today, including environmental and social policies.

The myth has been that the economy (and government balance sheets) improved due to the tax-cutting, free-trading deregulation and neoconservative economic policies of the governments of the 1980s through to the early 1990s: Thatcher in the UK, Reagan-Bush in the US and Mulroney in Canada.

Then following the recession of the early 1990s, traditionally “liberal” parties shifted rightward through the 1990s and 2000s — New Labour’s Tony Blair, Democrat Bill Clinton and Canada’s Chretien Liberals, all of whom brought their government budgets to surplus. (Ironically, Thatcher, Reagan and Mulroney all ran huge deficits and accumulated record debt).

Hamilton suggests that energy and oil underpins it all.

The “malaise” of the 70s was due to high oil prices, the recovery of the 80s under conservative governments was due to a drop in oil prices, as was the “boom” and surpluses of the 1990s under liberal governments.

This of course, makes sense: industrialization is driven by cheap and abundant energy, by coal in England during the industrial revolution and oil and natural gas in the mid 20th century U.S. China’s industrialization, likewise, has been driven by cheap coal.

Today, agricultural production is also driven by the oil prices, because not only fuel but fertilizer is made from petroleum products.

Whether oil or not, energy markets tend to fluctuate together. When oil prices soared, other sources of energy also failed of their promise.

In the early 1970s, U.S. natural gas shortages meant that power plants closed or switched to Middle Eastern oil, which had less sulphur than North American oil, over environmental concerns.

Meanwhile, steam-powered plants were hitting practical barriers: generally speaking, the hotter an engine can run, the more efficient it is. The trade-off is that at peak temperatures, it starts to damage moving parts, requiring expensive repairs.

Nuclear power turned out to be expensive and difficult to manage. Aside from scares over radiation leaks, there were other concerns about nuclear power, including discharging too much hot water into the environment.

The collapse of the USSR may also have been tied to oil shocks.

“Soviet oil production dropped an astounding 50 per cent between 1988 and 1995 from 12 million barrels to seven million barrels. (Under Putin it has returned to 10 million barrels.) As oil drained from the Soviet machine, the nation's stability morphed into Russian chaos and a temporary political renewal... Satellites of the Soviet Union also went into energy descent. Deprived of cheap oil and subsidized fertilizers made from cheap natural gas, North Korea experienced a famine and Cuba fell into an economic and agricultural crisis known as "the Special Period."

Debt: an extra destabilizing factor

For Canada, the change in the price of oil in the 1970s was also massively disruptive. As you can see from the top chart, capital investment in the Canadian oil industry was on an accelerating curve until about 1979-1980. In 1979, the Iranian Revolution, where the Shah of Iran was overthrown.

“Stagflation” was the problem - rising prices and stagnant incomes, and the political and macroeconomic response in the U.S., Canada and the U.S. was to completely change economic systems. It was determined that Keynesian economics didn’t work, and that Milton Friedman’s prescriptions to fight inflation would have to be used instead.

Inflation was seen as something internal to the economy - that there was too much money flowing around that was driving up the prices of workers and goods. So what had to happen was to break the cycle of giving people wages and price rises.

Central banks — in the UK, US and Canada, all adopted similar inflation-fighting policies of the kind recommended by Milton Friedman: allow for increased labour mobility, lower taxes, lower interest rates - which is a polite way of saying the labour market needs to be more volatile, and workers need less job security.

Under Jimmy Carter, a bill was passed making inflation fighting part of the Federal Reserve’s mandate. Corporations started to adopt a practice known as “shareholder value” (also inspired by Friedman, which we will get to later), and when Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were elected, they both adopted Friedmanite policies

This was in fact the solution, and it was achieved by Paul Volcker, Chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, through sustained hikes in interest rates up to 18% in the U.S and 21.94% in Canada. This rewarded those with cash, while people and businesses could generally not afford to borrow. Unemployment rose, businesses failed, and the rate of inflation dropped. Some areas of the U.S. had unemployment of 25%.

The general tale is that inflation was tamed, and an economic recovery followed. But the economic crisis of the late 1970s and early 1980s was also happening at the time of the Iranian revolution, which aside from creating a geopolitical crisis with American hostages, also made the world price of oil spike to a new high of $30 a barrel - more than 15 times what it had cost a decade before.

Inflation dropped below its peak levels of over 14% in mid-1980 to just under 4% by the end of 1982.

Chart – historic CPI inflation Canada (yearly basis) – full term

However, something else occurred at the same time: the price of oil finally dropped - and continued to drop for six years before collapsing in 1986. The effect of the price of oil - which also underpins the value of many currencies - undoubtedly played a role in inflation going down. But if the price of oil increases creates shocks an order of magnitude greater than what they crowd out, as Hamilton suggests, it also makes all the other things oil depends on cheaper as well.

At the time the Canadian Government introduced the “National Energy Program” - which was blamed for all the problems in the oil patch. There were certainly arguments against the NEP, but the fundamental forces at work were global oil prices, as well as massive increases in interest rates.

Not only did hiking interest rates to 20% decimate manufacturing (in Canada, the U.S. and the UK) it meant that much of the new oil development that was taking in place in Alberta and Saskatchewan - including people’s mortgages - was at 20%.

As tends to happen, people assumed that the cost of oil would be high forever - but when the crash comes, not only do revenues drop, but all the capital investment and growth ceases as well.

So individuals, businesses, and governments all have less revenue to service the debt they have taken out in anticipation of future revenue.

What’s more - as energy prices drop, the rest of the economy tends to rebound. The exchange rate tends to drop, making it easier to export, and generally fuel costs are lower.

This makes for a difficult economic and political challenge: one part of the country, which was booming, suddenly faces Depression-level economic straits.

The result is what people call “populism” - when it is economic desperation. As I have written before, financial crashes drive political extremism - especially to the right.