The Outsized Impact Oil Price Shocks Have on the Economy

A $1 Increase could lead to $10 worth of disruption

It is obvious enough that when the price of oil goes up, it will affect the economy.

He tracked more than a century in oil shocks and shortages. Some were sometimes political - strikes, wars, cartels, and some were related to changing access.

Hamilton argues that the higher oil prices don’t just “crowd out” other purchases - if you have to spend $10 more filling your gas tank, it doesn’t just mean that you will spend $10 less somewhere else. He argues that the economic impact may actually be an order of magnitude higher than the price increase alone.

Economists tend to focus on money and interest rates or economic policy as being the big factor in everything. They think work depends on money. But work - depends on energy. It is used to get raw materials, and process them into something workable before they are manufactured, distributed and sold. (Workers - even junior vice-presidents! - need to eat, too.)

Industrialized societies depend on cheap and abundant energy. This was true of coal in England during the industrial revolution and oil in 20th century North America.

In fact, the collapse of the Soviet Union has been attributed in part to oil shocks.

In fact, the collapse of the Soviet Union has been attributed in part to oil shocks.

This is significant from a number of perspectives - for the economy and the environment.

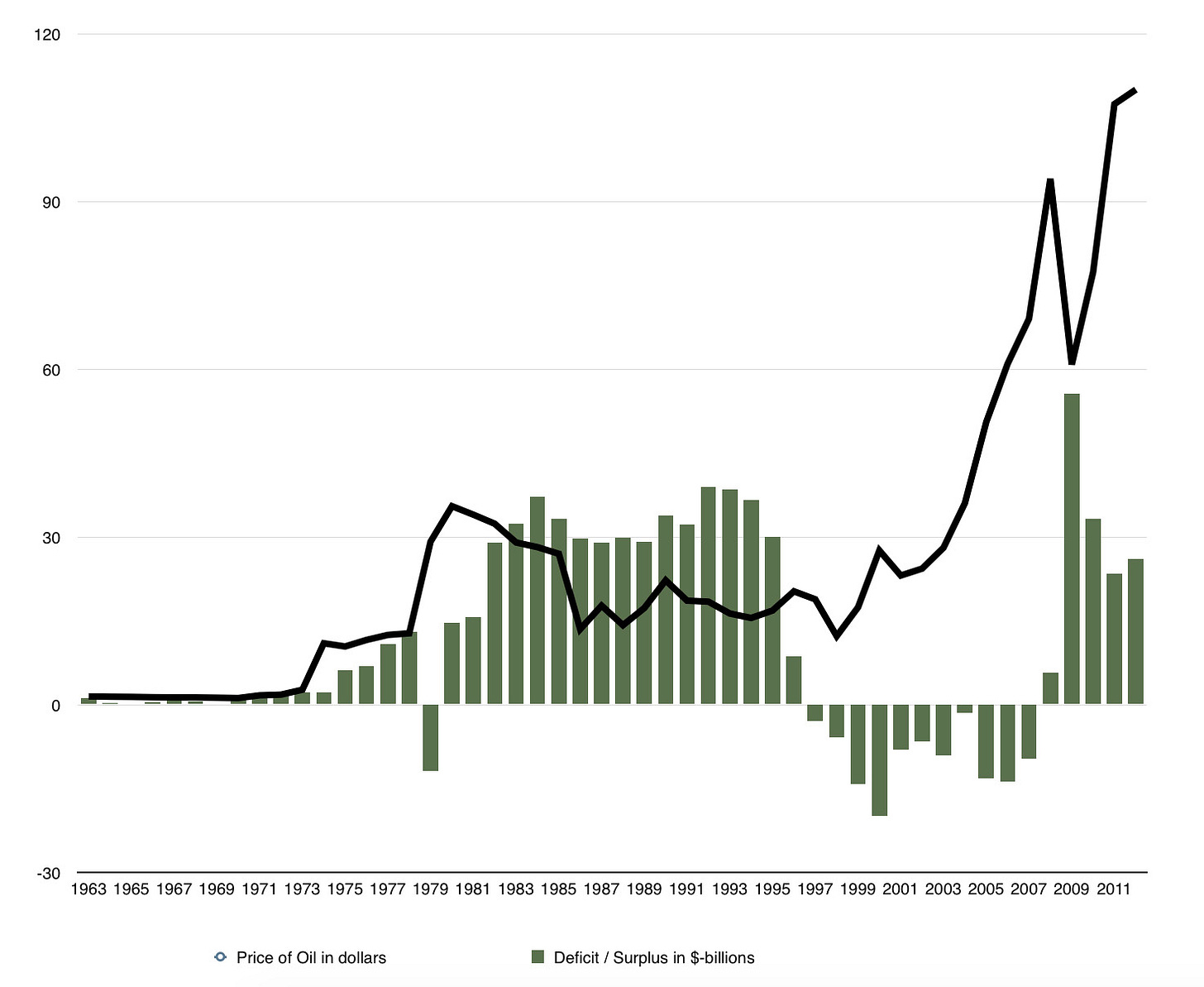

The oil shock of 1973 was colossal - after years of flat prices, it increased 300%, and spiked up again by 128% in 1979. The 1973 shock was caused by the OPEC Oil Cartel, the 1979 one by the Iranian revolution. Since then, there have been price shocks both up and down. During the pandemic, prices went negative, then soared when Russia invaded Ukraine.

In Canada, massive government deficits and debt are often blamed on the Liberal Government of Pierre Trudeau - because Trudeau got them “started” and interest rates meant they couldn’t be contained, or that Trudeau’s National Energy Policy was to blame for people in the Alberta oil patch losing everything in the 1980s. In fact, the price of oil may underpin it all.

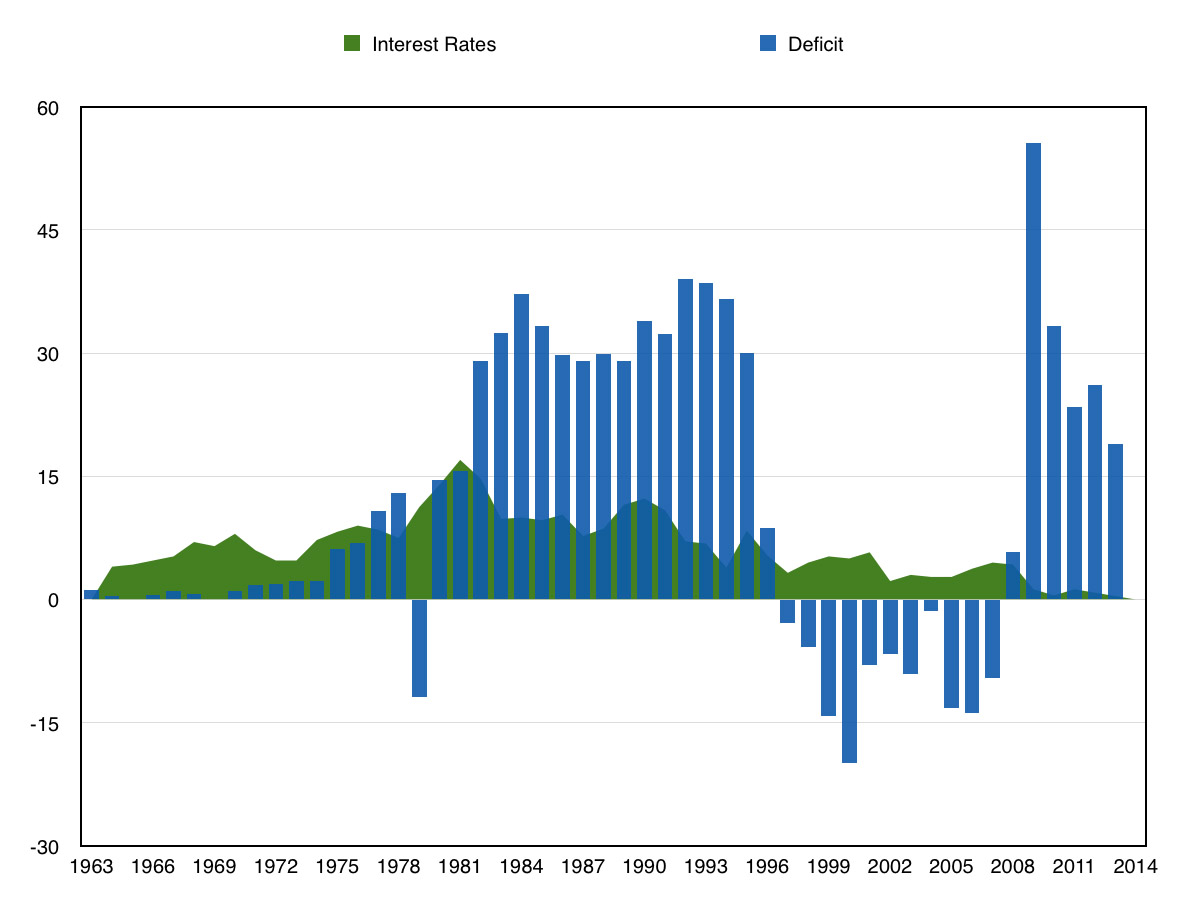

It’s important to recognize that Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher both ran colossal deficits in the early 1980s, and the decision to raise interest rates was an attempt to wrestle inflation under control.

To do that, they used a new prescription for fighting inflation, from Milton Friedman: less regulation, lower taxes, greater “labour mobility.” That is because Friedman’s idea of inflation was that it was “too much money chasing too few goods.”

Almost all of Friedman’s policy ideas, when put into practice, have not worked. Even conservatives suggest that he may have been “wrong about everything."

Oil Prices vs. Deficits (Canada)

Deficit vs. Interest Rates

As the oil price vs deficit charts shows, there is generally a lag between the price of oil and the impact on the deficit.

The high sustained deficits of the 1980s follow an interest peak in the early 80s - it reached over 20% in Canada. The deficit chart would be similar in Canada, the US and the UK - high deficits in the 70s and early 80s, surpluses in the 90s, going back into deficit in the 2000s.

Balancing the revenue generated by energy exports and the way it affects the whole economy due to exchange rate impacts is a challenge for any oil exporting country.

There are other challenges around the idea of Canada being an "energy superpower” especially when it comes to the tarsands.

Tarsands oil is a “manufactured oil” - it takes a lot of work (and energy and water) to “make” a barrel of oil, or bitumen, that can be refined into gasoline, oil, or other products. That costs money,. Oil in places like Saudi Arabia and the middle east is “light, sweet crude” that is close to the surface and can be extracted for a lower dollars a barrel. Both are sold at the world price.

That means that the tarsands only make economic sense when oil prices are over a certain level. This is why, around 2015, Alberta went through a major slump, and has since recovered. In 1986, oil dropped down to $13 a barrel when in 1980 it cost $35.

That is changing - still, for a challenging reason, is increasing automation. Driverless trucks and other advancements mean fewer people working in certain jobs.

There are plenty of people - including The Economist - who have pointed to the risk of “Dutch disease" for Canada. The argument is that, In Holland in the 1970s, Dutch production of North Sea Oil resulted drove up their currency, making it harder for them to export goods, hollowing out their manufacturing sector.

Currency Volatility

The reason finding oil is disruptive to a country’s economy, is for two reasons. First, they will likely be exporting that oil, not using it entirely for themselves. Oil is priced in US dollars. If you are Holland in the 1970s, people who want to buy your oil have to buy Dutch guilders in American dollars. The same thing happens with Canada, right now.

When the price of oil was over $100 a barrel and Canada’s dollar was on par with the U.S., it’s because so many people were buying oil from Canada, and to buy that oil, they had to buy Canadian dollars, using American dollars. And it was happening so much - we were exporting so much oil and gas, that the “price” of the Canadian dollar rose on currency exchanges because people with American dollars needed to buy so many billions in Canadian dollars.

What this means is that this one commodity - energy - is affecting the entire Canadian economy because of the way it is affecting the currency. And it affects everyone else who is an exporter, because whether they are seeking to compete with current markets, or are dealing with long-term contracts where they have already committed to. All of a sudden, their customers have to pay much more than they expected on the exchange rate, to buy the Canadian dollars they need to pay for the product.

(This is why countries that are federations - a central government and provinces or states, with a single currency, must have adequate transfer payments in order to function. There is a real cost to having a shared currency, and that is why not having them leads to crisis. I will address this in a future article about the EU.)

One direct impact was on manufacturing. This was evident in the auto industry, which had plants in the U.S. and southern Ontario with parts and assembly flowing back and forth across the border.

All of a sudden, the U.S. manufacturer faces a huge spike in costs because of the exchange rate. It makes imports from other countries more appealing.

Theoretically, a strong Canadian dollar compared to other currencies - means imports drop in price. Good for consumers, but it’s a challenge to domestic competitors on that front as well.

The drop in Canadian productivity coincided with the rising price of oil and Canadian dollar. So while the oil industry can bring in huge amounts of money, it employs relatively fewer people. Manufacturing tends to employ more people at higher wages. Service industries tend to employ a lot of people at lower wages, though it depends on the service.

The provinces of Ontario and Quebec both lost hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs between 2000 and 2011.

As the energy crisis of the 1970s showed, soaring oil prices were a problem for manufacturing whether you lived in an oil-producing country or not.

It is literally impossible for everyone to work in the oil sector: in Alberta, 139,000 people, or 7.1% of the population work directly in the oil industry. In turn, they produce 25% of that province’s GDP, 33% of the provincial government’s annual revenues, and 50% of the province’s exports. Alberta’s economy has grown quickly since 2000 because the price of oil has increased, but between between 2000 and 2009 (though this includes a sharp recession after 2008) Canada as a whole lost 500,000 manufacturing jobs.

The price of oil has increased, and the exchange rate for the Canadian dollar changed rapidly. In the mid 1990s, the Canadian dollar was as low as 63 cents U.S., (and the U.S. Dollar cost $1.50 Canadian to buy) then increased to trade around par. The change was too sudden for most Canadian manufacturers, who depend on export markets, to adapt - other than through outsourcing production. The 2008 financial collapse and soaring unemployment in the U.S. was also a factor.

There was more to the change in currency valuation than the price of oil: in the 1990s there were a number of major international financial and currency crises (Mexico, Russia, Asia) that resulted in investors fleeing other markets and pouring their money into the U.S., which was perceived as a safe haven.

There are anti-tarsands activists who argue that, in order to prevent climate change, all the oil in the tarsands needs to stay in the ground.

But there is clearly a problem for Canada’s economy (including its deficits) because the Tarsands can only turn a profit if oil prices are high. If oil prices are high, so is the cost of everything else.

This is a difficult economic, environmental and political trade-off to negotiate.

If the price of oil drops, lower energy costs will be much better for the economy: and for industries - but the industries still need to be there to be revived.

The current conflict in Ukraine, Crimea and Russia is a problem not just because it has every likelihood of sparking a much wider military conflict, but because the economic impacts may be felt almost immediately and they will also make things worse.

The price of oil is already going up. Russia is the major supplier of oil and gas to Europe. That was part of the point of invading Ukraine - the assumption that Europe was captive to its energy markets, and would refuse to intervene.

: this means it is in a position to choke off energy, especially to Germany. In the past, Putin has simply threatened to shut off oil supplies to Ukraine.

Aside from the fears of military conflict and war, an oil shock will risk making the European economy even worse, which means a downward spiral of conflict and economic problems that will spread through global markets. This is a risk, even if the conflict is resolved.

One thing that would make a difference in terms of domestic price stability would be to have more of processing of bitumen or oil into its final product here in Canada. It may need to be considered for the sake of energy security. It would face environmental objections. We should still be pushing forward as hard as we can on climate change. The idea here is to ensure Canadians are not in a position where someone else can turn off our energy.

People sometimes ask how is it that Norway has managed its oil so differently. It is for a number of reasons that contrast sharply with Alberta and Canada.

First, in Norway, it is a federal responsibility, not provincial. This makes a big difference, because royalties and revenues are collected nationally, for the benefit of all. In Canada, natural resources are a provincial responsibility. The other is that Norway was careful when they discovered oil in the 1960s. They figured that if this was a limited resource, they would make the benefits last. Instead of extracting as much as possible, the Norwegians allowed for limited exploration for oil. They collected revenues into a national fund, and they used that money to invest abroad, to prevent inflation in Norway. This, at least, addresses the issue of “Dutch Disease” by ensuring that everyone is benefiting from a natural resource - though not without challenges.

It has to be recognized that this is a natural resource whose price always sends shock waves through the economy, because we all rely on it so much. We have built a society, where we cannot access the necessities of life without using oil. For most of us, it may be a challenge to access necessities of life without in some way involving or requiring oil to access it.

For that reason, this makes the development of alternative, climate-friendly energy sources even more urgent - because overreliance on a single commodity is a strategic vulnerability. Having alternatives and backups - redundancy in the system - reduces both vulnerability and volatility. It’s what actually makes economies “robust” as people like to say.

-30-