The Smoot-Hawley Tariffs Did Not Cause the Great Depression. Austerity Did.

Trump is getting economic history disastrously wrong, but so are his critics. Anyone? Anyone?

In the midst of what is increasingly looking like an economic fiasco of global proportions created by the White House, it has to be said that while Trump’s policies are delusional and reckless, the criticisms of his policies are too.

The economic arguments about the impacts of tariffs keep getting compared to a bill introduced in the Depression by two Republican congressmen - Hawley and Smoot - who sought to stop the bleeding with tariffs. Experts, pundits, journalists and partisans all keep repeating the same claim that these tariffs are to blame for the Great Depression.

The problem with this argument is that it’s not accurate. Not only is their evidence that the tariffs were not the problem, and that austerity was - there have been a string of more recent financial crises since 1989 that tell a completely different, and more accurate story that no one else is telling.

Instead, I received a Business Brief from my local newspaper that talked about the new tariffs Donald Trump has imposed on the world, which said

“It is so strikingly similar to a tariff act — the Smoot-Hawley tariffs — that launched or at least exacerbated the Great Depression, it beggars belief.”

The number of experts repeating these claims include - Bloomberg commentators, Economics professors, business experts as well as Trump’s critics.

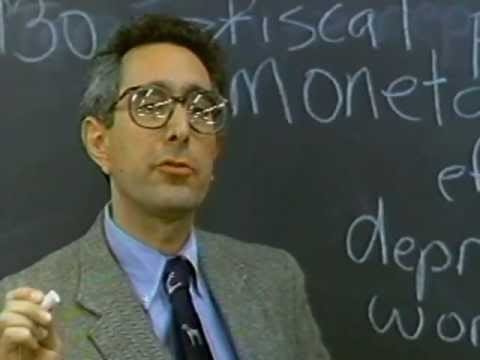

This clip about the Smoot-Hawley tariffs has been circulating as a lesson in the danger of tariffs. What people don’t realize is that Ben Stein, who plays the deadpan teacher in the clip from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, worked in the Nixon White House and is very right-wing economically.

I also received an e-mail from the Fortune 500 Digest, which cited the claim several times.

Wharton emeritus finance professor Jeremy Siegel: It's the "biggest policy mistake in 95 years...I don’t know why Trump didn’t learn the lesson of the Smoot-Hawley tariff."

It linked to another article, arguing that Trump’s tariffs could be worse than Smoot-Hawley.

“In June of 1930, just eight months after the historic stock market crash that marked the start of the Great Depression, Congress enacted the Smoot-Hawley tariff law...the average rate rose to just under 20%. That’s slightly below the 22% or 23% I get for the Trump plan. And that’s stunning in itself. But the most astounding takeaway is that the Trump blueprint would raise today’s tariffs from the current 3% by nearly 20 points, or sevenfold! That’s three times the jump under Smoot-Hawley.

“In the three years following the enactment of Smoot-Hawley, U.S. imports dropped by two-thirds, and, pounded by stiff retaliation from nations such as Germany, the U.K., and Canada, our sales abroad fell by a like percentage. According to most economists, the Trump tariffs are likely to unleash a sharp decline in both what we buy from foreigners and what our producers sell abroad in the years to come, and if the shrinkage in our global trading activity proves even a fraction of the disastrous collapse post-Smoot-Hawley, it’s bad news.”

For more, read Shawn's piece here.

Yes, Trump’s Tariffs are a Disaster, but Not all Tariffs Are

Don’t get me wrong: Trump’s tariffs as deployed are reckless and dangerous. Trump is demanding “tribute” by turning the U.S. government into a global protection racket, as this excellent analysis argues, in a similar move that led to the fall of the Athenian Empire. Because they were powerful, they started asking to be paid for their alliance.

Just doing trade with the U.S. isn’t enough: countries will have to pay for the privilege, and being allies isn’t enough - we’ll have to pay protection money.

The payments are made by are asking others to “share the burden”.

There are lots of reasons this is a fatal mistake, because the “burden” is the “burden” of power, and the power and control is defined by the dependence of others.

The dependence on the actions of a central power is the very relationship that makes the centre powerful.

First, by turning on allies any new arrangements are poisoned by resentment.

Second, and more seriously, it destroys the entire power relationship: instead of others depending on the centre, the centre depends on others.

Trump is making a colossal mistake - many of them - because he is making the United States an unsafe place for people to put their money.

Trump’s claims that the U.S. was at its richest from 1870 to 1913, before income taxes, was also a period when the London and the British Empire was the global power. It was after 1913 that the financial centre of the world shifted from London to New York.

Trump and his administration’s focus on the US federal government’s debt of $36-trillion and the efforts to balance the budget or run a surplus are a much bigger threat to the U.S. Economy, because that is what caused the Great Depression: the U.S. and other countries focused on balancing their budgets, restricting spending and investment,

Austerity and Cuts, not Tariffs Are What Caused and Deepened the Great Depression

First, it’s important to understand roughly what happened in the lead-up to the Great Depression of 1929.

The “roaring 20s” in the U.S. - the era of the Great Gatsby there was already global economic turmoil following the First World War.

The U.S. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon had kept interest rates low, which led to “easy money” - readily accessible credit. As today, instead of that money being ploughed into new “greenfield” investment - new factories, etc., the money tended to inflate the price of existing assets - stock market shares and real estate, in places like Florida.

In 1929, Wall Street crashed, and the financial crisis led to a global economic meltdown.

This chart compares the 1929 crash and first years of the Depression vs. the Global Financial Crisis, or (Great Recession) of 2008.

It’s notable that the economy was already faltering before the market fell. The Economic contraction started in August, and the crash itself didn’t occur until the end of October.

The impact in the U.S. and around the world was devastating. In the U.S. alone, there were 9,000 bank failures, a 50% drop in industrial production, and a drop in the Dow Jones (which had a completely different makeup in 1929) of nearly 90%.

The idea that Smoot Hawley tariffs are to blame comes from a very specific, laissez-faire economic viewpoint. It’s the idea that any government action is bound to create “friction” and mess things up in the otherwise smoothly-flowing machine of a market. It blames government interference in the market as being the problem for everything, including running deficits to get the economy going again when it has collapsed.

So the same economists who believe that Smoot Hawley was to blame for the Depression don’t blame the decision to try to keep trying to balance the budget, even when 9,000 banks had failed and unemployment had increased by 20%.

Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon famously said

“Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate. It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up from less competent people.”

They don’t recognize the harm of austerity. We still have not learned the lessons of austerity, even as they drive horrific division and conflict around the world, between countries, and within our own societies.

As I have noted, a history of 140 financial crises around the world showed that societies polarize when the crisis is left to fester, resulting in deep divisions, and far-right nationalism. Austerity after a crash leads to far-right, authoritarianism, and as Mark Blyth found in his excellent book, it has never, ever worked in a slump. It can only work when the economy is growing faster than the cuts.

I recall my father telling me many years ago that while inflation could be bad, deflation could be worse, and debt on real estate and the price of property plays a major role. Whether it’s a farm or a mortgage on a home, or a loan for a small business, if the economy collapses and prices and wages tank, it makes it that much harder to pay off your debts. You get “debt-deflation” because the dead weight of debt means the economy can’t get off the mat.

Ha-Joon Chang writes that:

“One influential view, propagated by neo-liberal economists, is that this large but totally manageable financial crisis was turned into a Great Depression because of the collapse in world trade caused by the 'trade war', prompted by the adoption of protectionism by the US through the 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariffs.

This story does not stand up to scrutiny. The tariff increase by Smoot-Hawley was not dramatic - it raised the average US industrial tariff from 37 per cent to 48 per cent. Nor did it cause a massive tariff war. Except for a few economically weak countries such as Italy and Spain, trade protectionism did not increase very much following Smoot-Hawley. Most importantly, studies show that the main reason for the collapse in international trade after 1929 was not tariff increases but the downward spiral in international demand, caused by the adherence by the governments of the core capitalist economies to the doctrine of balanced budget.'

That is explained in a BBC article here.

The major focus of many economies is on governments balancing the budget, when the problem is that the private market has failed.

Part of the reason for this is that the mathematical models of classical and neoclassical economics assume that markets cannot crash. They don’t actually model debt.

Because they see austerity as good and necessary, they don’t recognize that it is the problem. If the economy is a patient in hospital, austerity is a tourniquet, except instead of stopping the bleeding on a severed limb, practitioners apply it around the patient’s neck.

The thing is, there is no question that a collapse in real estate and property prices, as well as waves and defaults where people lost homes and farms is what defined the crisis at the beginning of the Great Depression.

Part of the reason for the perception that liberal democracy would end in the 1930s and be supplanted either by Soviet-style Marxist-Leninist Communism, or German-style Fascism, which had been branded as “National Socialism” was that the controlled Soviet Economy was actually performing better than the “free” economies of Great Britain, Europe and North America.

Countries everywhere followed austerity policies: Japan, Great Britain, Canada, the U.S., Germany, France. The results were to further shrink their economies while increasing debt and driving political instability. The Soviets also managed to engineer the starvation of millions of Ukrainians. Part of the reason for the Soviet growth was the many oil refineries they built with help from the Koch family.

In effect, there has been an ideological and economic denial that FDR’s New Deal is what got the US out of the Depression, which is in defiance of reality and history. There is no question that FDR’s actions and policies in the U.S., as well as the actions and policies of Mackenzie King in Canada after 1935 made colossal differences in reviving the economies of both countries.

It’s actually pretty bizarre that we only ever talk about the Great Depression, when there have been colossal financial crashes within living memory, including in Japan in 1989, the US and the world in 2008, and in the EU in 2010.

In 2008, we know that when financial structures collapsed, the fundamental building block was the American mortgage. Bad mortgages were packaged into bad investments, which were rated good by bad ratings agencies, against which people took out huge amounts of bad insurance. There was also rampant criminality.

However, instead of getting a New Deal, Americans did not significantly reform their financial institutions - no one was convicted.

This kind of financial mania, or craze, has happened throughout history, and the craze can seize onto all sorts of different kinds of property - gold mines, railroads. There was a “South Seas” Bubble, and the “Mississippi Scheme” where people thought there would be fortunes made from untapped mountains of gold or silver in Chile or Louisiana.

The property can also be virtual: in the dot.com craze in the 1990s, which was also fuelled by ultra-low interest rates, people were spending $1-million for domain names, and it gave rise to my favourite joke about when the market has become irrational:

Tech Bro #1: “How’s business?”

Tech Bro #1: “We’re losing money on every sale, but we’re making up for it in volume.”

The thing is, at the centre of the chaos of these crazes, there is usually some seed of true value. There was real value in tech, in certain companies who were making incredible amounts of money from sales.

Lessons From the Biggest Crash in the World

Another example of what happens after a financial crashes is Japan, which after years of growth that was driven by innovation and ever-increasing improvements in engineering, started to produce high-quality, lower cost goods, including vehicles and electronics - TVs, VCRs, cameras, for example.

In the 1950s, after the second world war, Japan was known as a place where cheap, low-quality goods were made. Over the years, their low-cost goods became higher quality household names. Sony started selling transistor radios, then became a technology giant. Toyota and Honda both made small, low-cost cars that eventually became known for reliability and eventually developed luxury brands.

By the 1980s, Japan had become a global economic powerhouse and was selling huge amounts of goods to the U.S. and around the world.At the same time, Japan’s real estate market went wild.

At one point in 1989, Japanese real estate was worth 50% of all the property in the world.

Consider that for a moment: the Japanese real estate market was worth the entire rest of the world combined.

Consider how insane the consequences of those valuations were: 1.3 square miles near the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was worth all of California. Another suburb was worth all of Canada. The value of all this real estate was fuelled by debt and by Japanese banks. Japanese banks were among the largest in the world.

In early 1990, the Japanese stock market, the Nikkei, crashed and the housing market collapsed shortly thereafter. When prices started to drop, the banks started to go broke. Many corporations and people were weighed down with colossal debt. Technically, many corporations were bankrupt, because they owed much more than they owned - except they still had cash flow. They were “zombie” companies - even though they still workers being paid, making products and provided services, and taking in revenue from sales.

As economist Richard Koo explained, Japan tried just about all the things that other countries did after the 2008 crisis - and it didn’t work. This included guaranteeing bank liabilities, quantitative easing (printing money to buy bad assets from banks), and running a deficit to stimulate the economy, and zero percent interest rates. After seven or eight years, they realized that corporations were not trying to maximize profits - they were trying to minimize debts. Even with zero percent interest, companies were not borrowing to invest - for a full ten years, between 1995 and 2005. In fact, they were paying down trillions of dollars in debt - equivalent to 6% of Japan’s entire economy.

As Koo says, of course it makes sense for each individual to pay down debt - especially if they they owe much more than what they own is worse. They are not going to borrow, because they are already in too much debt. When this happened in the Depression, in the US from 1929 to 1933, the economy shrank by half.

This is Koo, from 14 years ago - talking about how every exceptional measure used by governments in the U.S. and elsewhere to deal with the financial crisis had all been tried in Japan ten years earlier.

In fact, this is probably one of the most important and informative explanations of went wrong in both Japan and the Great Depression (I also quote it at length below.)

When people talk about a “financialization” and others rabbit on about “late stage capitalism” without any real plan to transition to anything else, what Koo is describing is the problem with the way the financial economy has massively distorted the real economy, our society and ultimately our politics.

There is too much private sector debt: many people and businesses are effectively insolvent, or bankrupt, right now. The reason they are not is that they have cash flow, and they can service their debt. And if the cash flow stops, right now, they will be bankrupt for real.

That is the problem with the global economy, right now. But Koo’s explanation is outstanding.

“It's like a replay of what we just went through”

“Well, there's great deal of confusion in both the US & UK Euro area about what is the right approach to this current crisis.

A lot of things were tried:

zero interest rates

quantitative easing

massive fiscal stimulus.

Then, you come with

a budget deficit, with it guaranteeing bank liabilities.

Capital injections to the banks

You know, these highly unusual measures.

Well, we in Japan went through all of it. Every one of the things that were put in place we had to do it 5-10 years ago, or sometimes 15 years ago. And so, for those of us who are in Japan looking at what's happening, what's unfolding abroad, it's like a replay of what we just went through and all the confusion in the policy debate - whether there should be more fiscal stimulus, or less. Whether monetary easing can compensate for less fiscal stimulus. You know these things - we discussed it in Japan 10 years ago.

And at first. when we were going through it there was nothing else to look at because anything that resembled Japan in the past you had to go back all the way to the Great Depression in the United States - and that's a different country, in a different era.

So, there was a great deal of trial and error, not knowing what is the right thing to do and it took us about seven eight years into the recession before we realized that this is actually a different disease.

This is no ordinary recession. Ordinary recessions happen because there's over production of some sort - inventory build up, or there was some inflationary pressure - the central bank is tightening monetary policy.

Those are the typical reasons we fall into a recession.

But the one we fell into, people were no longer maximizing profits: they were minimizing debt.

And even with zero interest rates, companies were paying down debt. And no business schools or Economics Department anywhere in the world have suggested that such things should take place.

These things are not supposed to take place. Because if companies are paying down debt in the environment of 0% interest rates that suggests under ordinary theories that corporate executives are so stupid they can't find good use for the money, even with zero interest rates.

Then, why should these companies be around? Companies should just give the money back to the shareholders, and let shareholders find something better to do with the money. That's the usual interpretation.

And so, something like that was not supposed to happen, but it happened in Japan for a full 10 years.

Rates are almost zero at 1995 short-term interest rates are zero at 1995 and corporate debt repayment continued until 2005. A full 10 years. And some of the bigger years the net debt repayment was over 30 trillion a year - 6% of Japan's GDP was net debt repayment.

So, some companies are borrowing, but so many more others are paying down debt. So the net was 6% of GDP going backwards.

And why is that so bad?

Well. first of all why did it happen? It's not that Japanese corporate executives suddenly went all berserk. They were doing it because they faced a balance sheet problem.

That is, during the bubble days, they borrowed tons of money to invest in all sorts of assets, thinking that they're going to make more money.

The asset price bubble collapsed : liabilities remained.

So, they realize that you have more debt than you can show on the asset side. And if your balance sheet is under the water, you're actually bankrupt.

Right?

But there are actually two kinds of bankruptcies: you're bankrupt with cash flow, or without cash flow. If you have no cash flow, and you're bankrupt, that's the end of the business. You have to raise your white flag, and you have to surrender.

But if you have cash flow and balance sheets under water, it doesn't matter whether you're Japanese or American or Dutch or Taiwanese or whatnot - that corporate executive will do one thing: use the cash flow to pay down debt.

Because, for all the shareholders and stakeholders of the firm, that's the best possible solution.

Shareholders don't want to be told that the company is bankrupt. Your shares are just a piece of paper. Bankers don't want to be told that their lending to the company was all non-performing loans.

Now, workers don't want to be told that there's no more jobs tomorrow because the company is bankrupt.

So, for all the stakeholders involved, the right thing to do at the corporate level is to use the cash flow to pay down debt.

Because asset prices never go negative. So, if you continue to pay down, there, at some point, your balance sheets will be balanced again.

You say, “I'm out of this problem, now we're going to start making money,” and so forth. So, it's just a couple of years - or at least that's what people think.

Well, that's the right thing to do at the micro level. When everybody does it all at the same time what happens to the macro economy?

Well, in a national economy, if someone is saving money, you better have someone on the other side borrowing and spending money to keep the economy going.

And in the usual economy - the one we assume implicitly in all these economics - is that if someone saves money, the money comes into the financial sector, the financial sector will find some other potential borrowers, the financial sector will give that money to whoever can use it, and that person will spend the money against the original income.

So if I have $1,000 of income, spend $900 myself, $100 saved - but this $100 go through the financial sector, Someone borrows it, spends it, and then so 900 plus 100 against the original income = $1,000.

If there are too many borrowers, you raise interest rates. Too few borrowers, you bring rates down. Someone raises and picks up the remaining sum and you go forward. That's basically the economy, as we know it.

What happens when you bring rates down to zero, and you still don't see anybody borrowing money?

Because, if you're actually bankrupt, & your balance is underwater, you're not going to borrow money at any interest rates, and no one's going to lend you money either, if they know that you're actually bankrupt, right?

And so, you bring interest rates down to zero. The $100 that this household saved gets stuck in the financial system.

No one's borrowing money. Everybody's paying down debt. So only $900 is spent.

So the economy shrinks from $1,000 to $900. The $900 is someone's income. That person spends it. That person decides to say 10%.

$800.

$10 is spent, $90 goes into the financial sector. That one gets stuck - because, as I said, the whole process took ten years.

So, if you leave this system unattended, you go from, 900 to 800 to 730 in no time.

And you might wonder - did anything like this ever happen?

Well, as I said earlier, the Great Depression in the United States was exactly this pattern.

US lost half of its GDP, in just four years - from 1929 to 1933 because everybody was paying down debt. No one was borrowing money.

In this type of situation, monetary policy is largely dead in the water, because you bring rates down to zero - nothing happens.

So, if the government wants to keep the economy from falling into this deflationary spiral, and because the government cannot tell the private sector “Please don't don't repay your balance sheets.” right?

The private sector has no choice. The private sector must repair its balance sheets.

So, the only thing the government can do, is to do the opposite of the private sector, and that is borrow the $100. The government still borrows it and spends it. Then $900 plus $100 against the original income of a thousand dollars, the economy moves forward.

That's basically what we realized was happening in Japan. And at first, we didn't realize that was the case.

So, we put in the fiscal stimulus: economy improves, and then we say, “Oh, the budget deficit is too large.” We cut it, the economy weakens again because the private sector is still deleveraging. And then, we put in another fiscal stimulus - the economy improves - and these people who have nothing better to do said, “Oh, the budget deficit is too large.” So, we cut it again, we fell.

So, we had this zigzag for a full 15 years. And because this is not in economic textbooks - because something like this not supposed to happen - as I told you, earlier.

No one gives us a direction of “what is the right thing to do” until we discovered it ourselves - that this is a different disease.

A completely different disease. It's not a common cold anymore. This is pneumonia.”

This is why economic Depressions happen.

In the mania in the lead-up to the crash, people and companies take on debt. It’s like a casino that is having huge payouts because everyone is borrowing money to speculate, because interest rates are so low and lenders will lend to anyone.

A huge amount of debt at low interest rates creates a trap for the entire economy: if inflation rises above interest rates, the lenders will start losing money, and they will go broke. If interest rates go up, borrowers won’t be able to pay debts, and they will go broke, and so will the lenders.

It is not what economists call a “liquidity crisis” - that banks don’t have enough cash on hand. It’s an insolvency crisis, because of what Koo described as “bankruptcy with cash flow.”

Companies that are “technically insolvent” with debt exceeding their value on their balance sheet can still generating value, putting people to work, buying and selling products and services, so long as the cash flow keeps coming in.

It’s musical chairs: as long as the music keeps playing and the money keeps flowing, they can keep working, paying their employees, etc., but if the music stops, it’s over.

That’s why austerity does not work. It cuts off the flow of funds into the private economy and collapses the finances of businesses and individuals aike.

The basic math of government spending is that if government is in deficit, the private sector and the economy is getting more money than they are contributing. The government deficit is a private sector surplus, and government surpluses are private sector deficits.

Trump’s tariffs are a disaster on many levels. First, they shouldn’t even be considered legal: the U.S. President is not supposed to be imposing tariffs, at all.

The real lesson of the Smoot-Hawley act is that tariffs are supposed to be set by congress, not the President. The fact that the Republican congress is allowing him to do so is an complete abdication of responsibility.

All of the complaining about Democrats not doing enough to stop Trump ignores that he has the White House and the Republicans hold the House and the Senate, and therefore that Republicans are entirely responsible for the current state of affairs, and are the only ones who can currently change direction.

The tariffs are a threat to the entire global financial order - of which the U.S. is the single greatest beneficiary. It is one of the largest tax and price hikes on Americans in history.

However, the threat of austerity is even greater: DOGE’s mass firings and the ransacking and vandalism of the U.S. government aim at cutting trillions of dollars in spending, which will cut off the flow of funds into the economy. All of the Republicans’ ideas and instincts are wrong.

Austerity cuts off the cash flow that is keeping technically insolvent people and companies from becoming actually insolvent, and it collapses them.

As Adair Turner wrote in Between Debt and the Devil, it is also why Keynesian fiscal stimulus alone can keep the economy going, but does not resolve the crisis. Governments running deficits to help the economy means that people and businesses pay down private debt, at the cost of adding to the public debt. The debt is transferred from the private sector to the public sector - and the correlation is 1:1.

When governments cut, the costs don’t disappear: they just shift the costs off their books and onto someone else instead.

This is the reason for economic stagnation and housing and affordability crises across the developed world - the U.S., Canada, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Europe.

Austerity turns insolvency crises into economic Depressions.

That is why economic renewal that provide genuine relief only occurs when the policies are introduced that reduce the burden of debt - government runs a high-pressure economy, so-called “financial repression,” or debt restructuring and debt amnesties. That is how the U.S. and Canada escaped the Great Depression. In Japan, the Bank of Japan took on a lot of debt.

As I have written, we are in a colossal economic asset superbubble - including a global housing bubble, which is driving reckless and dangerous politics and economic policies that are leading to utter misery.

This is not just a failure on the right, or the extreme right: it is a failure across the board. There are people on the far right as well as the far left who, because they don’t actually understand what’s wrong with the system, think the answer is to burn everything down, or that the the problem can be solved with still more debt.

What is required is a two-step: relief and tools to restructure private debt downward, so that existing businesses can keep functioning, and so that farmers and families do not lose their property. This reduces the excess burden of debt overhead that is the cause of economic stagnation, as well as providing widespread relief - it stops the economic bleeding.

Then, a transfusion of new equity into the economy can drive the recovery. It needs to be targeted and specific, but public investments in health, education and infrastructure are all rightly seen as an additional factor of production. These investments improve outcomes across society by creating greater stability and efficiency, and they reduce the cost of living and the cost of doing business.

The idea that we are condemned to live through painful recessions or Depressions is based on misguided economic beliefs when, as Richard Koo said, the reality of a “balance sheet recession” is not found or contemplated anywhere in economics textbooks.

Our economies are dysfunctional because they are massively “over-financialized” which is a fancy way of saying that for 50 years, the one solution to every problem has been more debt.

Countries that have monetary sovereignty, like the U.S., Canada, Japan and others, already have all the levers they need to achieve these goals. They are hamstrung by ideology that places an irrational taboo on the use of effective levers. It is not because they won’t work - it’s because powerful interests oppose the solution, because they stand to lose money.

It would actually reduce the concentration of wealth and income, because fewer people and companies would be paying debt with interest to a fairly small and concentrated number of very wealthy lenders. It requires asking plutocrats and oligarchs to take a pay cut - and show a little sacrifice, though it really is a reflection of the market reality.

What breaks our economies is that the biggest investors expect their investments to keep paying off even when they’ve gone bad, and for decades, the U.S. federal reserve in particular has been willing to ensure that happens.

In the midst of this market turmoil, as countries are girding their loins and ramping up “defense” in the midst of a global trade war, the reason multibillionaires are so wound up is that, having paid top dollar for a lot of assets, they are running out of other people’s money.

Austerity kills. As political scientist Mark Blyth has said, It has never worked, and it creates very nasty politics.

Margaret Thatcher was legendarily wrong. There is an alternative, and there always has been. The hard part is convincing or persuading people who have more money than God that they’re the ones who should be trying to do more with less, instead of everyone else.

- 30-

You mentioned the great depression. Many years ago I remember speaking with my wifes relatives who lived in Germany and Austria. A couple of the older Opa's mentioned that they remembered that just before the great crash/ depression you had shoe shine boys borrowing money to buy stock.....

At what point is debt relief the answer? I believe there have been times when this has been used... In ancient Greece? How did that turn out? Japan has very low unemployment, and almost three times the debt/gpt of the next highest indebted g20 countries... It seems like we have a lot of room to borrow more, as long as it helps grow the GDP...

Inflation has also been very low in Japan, despite massive borrowing and spending... And backs up the case against "government spending of course leads to inflation", which seems to be the received wisdom by almost everyone (99.999%)... History books will say that governments spending during covid, largely to keep people and businesses from collapsing, caused inflation... Poppycock! It was the artificially high doubling of oil prices in the aftermath of covid (likely so OPEC could recover lost revenue from covid), leading to wage push inflation and greedflation... global corporate profits moved from $100 trillion in the years before covid to close to $200 trillion in the years after... Inflation wasn't caused by giving crumbs to poor folks and struggling entrepreneurs...

Thank you for again highlighting the truth of where the real bogeyman are...