Why it’s cheaper to be rich and more expensive to be poor

Businesses put resources into cultivating rich customers and avoid poor ones. Left to run on its own, this has profound consequences.

In the 1990s, I was talking with a friend who was working at a Canadian bank, and he explained the 80/20 rule to me - and how a customer service program was scaled back because they were helping too much. Customer satisfaction reports were off the charts - to unheard of levels. In one instance, the bank had put someone in a taxi to deliver a new card to a customer who lived 90 minutes away from Toronto, and only did $14,000 worth of business with the bank. Bleeding money, customer service was scaled way back.

When I heard that ratio, I was absolutely shocked. It means that 1/5 of the population owns 4/5 of the property, and the higher you go, the greater the concentration of wealth. As someone who actually cares about inequality and people’s economic dignity, I have to say that learning this shook me.

80.20 was “discovered” by Vilfredo Pareto. Pareto was born in Paris in 1848 to an aristocratic Italian family, though neither he nor his father accepted the title. He was trained as a civil engineer, and made significant contributions to both economics and sociology with the pioneering use of mathematics and statistics, when before both disciplines had been more philosophical.

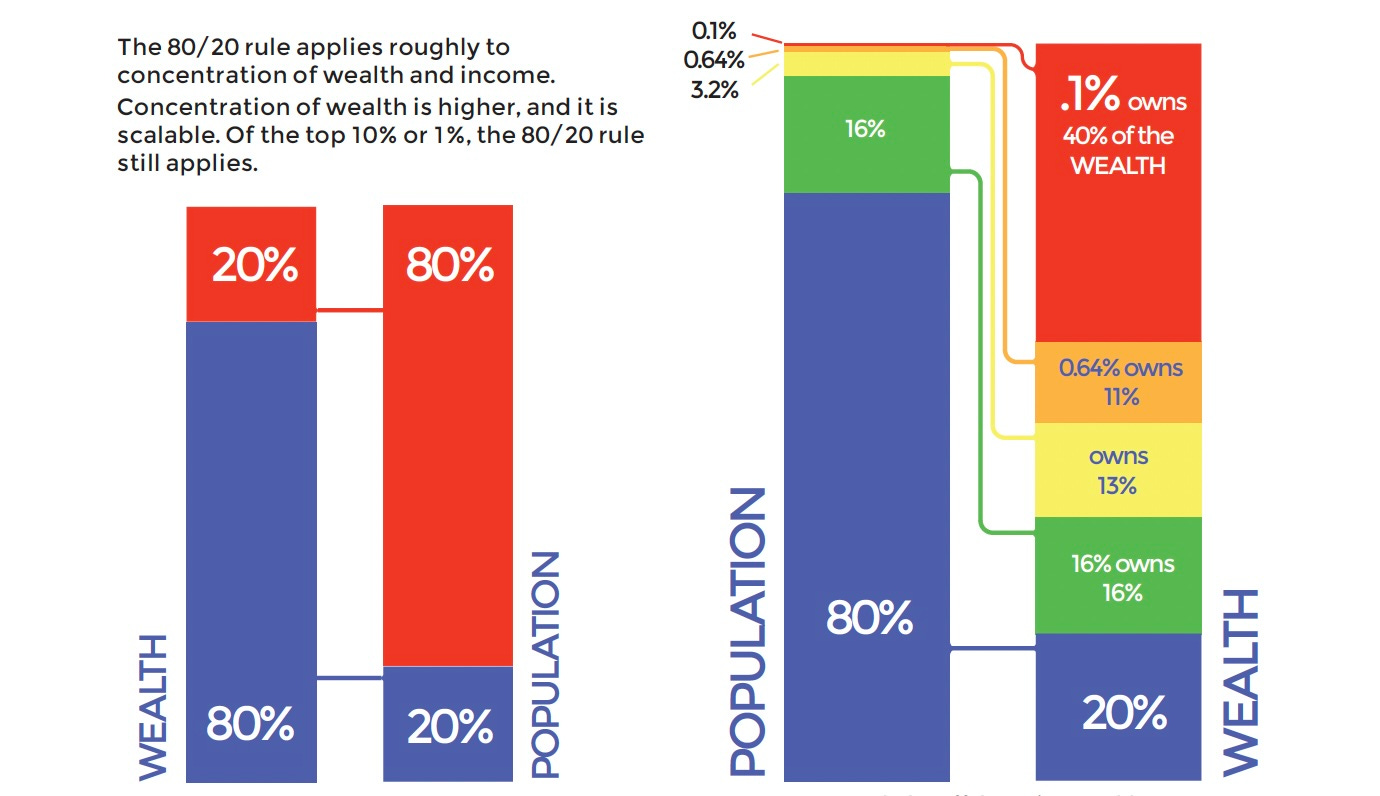

He looked all over the world and discovered what he thought was a universal rule: that in a given population, 80% of the land would be owned by 20% of the population. The inverse it also true: the remaining 20% of the property and income is spread amongst the other 80% of the population.

It is in many ways a shocking statistic, and an astonishing principle. It is said to hold true not only in individual countries around the world, but is true of the global population as a whole, and even of the ten wealthiest people in the world.

That is because, as Pareto discovered, the distribution of wealth follows a “power law” — (not in the sense of political power, but in the mathematical sense of “number x to the power of y”). Benoit Mandelbrot writes:

“What Pareto found, when he plotted income against the number of people … A power law was clearly present. In fact, his line sloped down instead of up, because the power was negative rather than positive. And alpha, Pareto’s name for the absolute slope of that line, was 3/2, he thought. What does that mean? Well, the gentler the slope, the more even the distribution of income...

Pick a group of people to study — say, everybody making minimum more than the U.S. government’s $5.15 minimum wage, or $10,712 a year. Now ask: What percentage of people earn at least ten times that? According to Pareto’s formula, the answer should be 3.2 percent. Now go higher up the moneyed classes. What proportion earns more than $10.7 million? Answer: 0.1 percent And once more: What proportion earns more than $10.7 million, a thousand times the minimum? Answer: 0.003 percent — a very small number indeed.”

In 2006, a UN study showed that the world’s richest 1% owned 40% of all wealth, and that 50% of the world’s adults own just 1% of the wealth. In the U.S., the imbalance is actually greater: in the U.S. in 2007, the top 1% had 42.7% of the wealth; the next 19% had 50.2% of the wealth, and remaining 7% of the wealth was split between the remaining 80% of the population. A 2009 study of Canada showed 3.8% of Canadian households controlled $1.78 trillion dollars of financial wealth, or 67% of the total.

Today, these levels of inequality are worse, because of economic shocks and central bank responses that have made the situation worse, not better, by injecting trillions of dollars of debt into the economy, which have minted new billionaires.

80.20 it’s a discovery — and a principle — that is both commonplace and scandalous. Commonplace, because it is has percolated down to everyday use in business and organizations of all types. It is assumed that eighty percent of your income will come from twenty percent of your customers, so if you want to become more efficient, you figure out which customers are your “best” and focus resources on keeping and cultivating them.

Scandalous, because Pareto’s discovery was not a cool assessment: it was tainted by a number of political judgments that earned him the praise of the Italian fascists, who adopted him as their own, and the monicker “the Theoretician of totalitarianism” from Karl Popper.

Benoit Mandelbrot writes:

"One of Pareto's equations achieved special prominence, and controversy. He was fascinated by problems of power and wealth. How do people get it? How is it distributed around society? How do those who have it use it? The gulf between rich and poor has always been part of the human condition, but Pareto resolved to measure it. He gathered reams of data on wealth and income through different centuries, through different countries: the tax records of Basel, Switzerland, from 1454 and from Augsburg, Germany in 1471, 1498 and 1512; contemporary rental income from Paris; personal income from Britain, Prussia, Saxony, Ireland, Italy, Peru. What he found – or thought he found – was striking. When he plotted the data on graph paper, with income on one axis, and number of people with that income on the other, he saw the same picture nearly everywhere in every era. Society was not a "social pyramid" with the proportion of rich to poor sloping gently from one class to the next. Instead it was more of a "social arrow" – very fat on the bottom where the mass of men live, and very thin at the top where sit the wealthy elite. Nor was this effect by chance; the data did not remotely fit a bell curve, as one would expect if wealth were distributed randomly. "It is a social law", he wrote: something "in the nature of man".

That something, though expressed in a neat equation, is harsh and Darwinian, in Pareto’s view ... There is no progress in human history. Democracy is a fraud ... The smarter, abler, stronger and shrewder take the lion’s share. The weak starve, lest society become degenerate: One can, Pareto wrote “compare the social body to the human body, which will promptly perish is prevented from eliminating toxins.”

Inflammatory stuff — and it burned Pareto’s reputation. At his death in 1923, Italian fascists were beatifying him, republicans demonizing him. British philosopher Karl Popper called him the “theoretician of totalitarianism.”

While Pareto’s 80/20 rule and the concept of “Pareto Efficiency” are both taught in economics, his politics aren’t generally mentioned.

In fact, as Mandelbrot notes, the ratio doesn’t hold everywhere in society — it tends to be true at the top, and it tends to reflect a concentration of wealth — or property ownership — more than income. But in both income and wealth there is huge inequality.

However, the shape of the curve that a power law creates is important when we talk about concentrations of income and wealth. That’s because the concentrations of wealth at the top can be so high they “pull up” the average.

On a graph, the curve always looks like this one - where the spike of the highest income actually would be about 50 times higher than the graph allowes.

Even if they are aware of the 80/20 rule, most people don’t think about its significance. It is generally left-leaning economists and activists who talk about the issue of income inequality, only to be dismissed by because they “know nothing about business.”

Business, however is one of the places where 80/20 is taken as a given. It is taught as an organizing principle in introductory business and marketing courses. Eighty percent of your revenue will come from twenty percent of your customers. Eighty percent of income taxes are paid by twenty percent of the population. Eighty percent of donations to charity are given by twenty percent of the donors.

Many philosophical, political, and economic theories do not take this distribution into account, or don’t consider what a difference it makes as a starting point when it comes to economic, fiscal, or trade policy.

The way we usually measure inequality contributes to our misperception. Often, economists and statisticians will split the population into large segments — “cohorts” or five quintiles of eighty percent each, with each fifth being averaged out. This analysis is blind to the distribution it is supposed to reveal, especially when it comes to wealth.

The 80/20 rule shows what a huge mistake this is: the top quintile — twenty percent — will have eighty percent of the total wealth (or income), and the bottom four quintiles will have twenty percent. Even within the top fifth of the population, eighty percent of the wealth will be held by the top twenty percent. And so on.

Quintiles use an average, spread out over a large population to measure concentration, which is a huge mistake. There is an “economists’ joke” that explains it: A cat is cornered by nineteen hungry rats. The cat doesn’t really have to worry, says the economist, because on average, not only is each rat is five percent cat, but the cat itself is ninety-five percent rat.

Averaging out the incomes of the top twenty percent of income earners in a population will make it as if a great many people have high-to-middle incomes. In the U.S., the top quintile starts at about $100,000 a year, but only two percent of Americans will make over $250,000 a year. In Canada, the top quintile starts at about $75,000 a year.

At the other end of the scale, statisticians can talk about how much mobility there is, but there will appear to be great mobility in bottom quintiles — because people are making $21,000 a year (the second quintile) instead of $19,000 (the first quintile).

We are also blind to distribution because it isn’t considered as part of GDP, which measures overall economic growth, but not how it is concentrated. The focus on GDP alone has served to obscure the fact that the concentration of wealth has been growing steadily for decades. In Canada,

“The typical household is now no better off, indeed about $3,000 worse off, than it was in the mid- to late-1970s, in spite of 35 years of economic growth.” In the U.S., wages have been stagnating for decades, even as stock markets have returned to record highs.

In response to complaints of an eroding middle class in developed countries, others will point to the fact that millions in developing nations have been lifted out of poverty. Here too, whether in China or India, the distribution has been incredibly unequal.

China’s explosive growth since 1980 has been hailed as a triumph for the free market and capitalism. Virtually all of the benefits have accrued to 20% of a population of 1.3 billion. With a population that large, improving the prosperity of hundreds of millions of people is no small feat, but as Ellen Ruppert Shell noted in her book Cheap:

“While the nation as a whole has grown wealthier, China’s poor have grown poorer. World Bank economists reported in 2006 that the real income of the poorest 10% of China’s 1.3 billion people had fallen by 2.4 percent between 2001 and 2003, to less than $83 per year. And this was during a period when the economy grew by 10% and the country’s richest grew by more than 16 percent.”

Under Deng Xiaoping, China abandoned central planning and embraced what is considered a free market economy, despite rampant state ownership that no one would mistake either for a liberal democracy or private capitalism. Even calling it state ownership may be a mistake. Rather, it is an inherited oligarchy. As Bloomberg news reported in 2012, the Chinese economic miracle is:

“the result of a conscious decision by the former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and some of his closest associates — the so-called Eight Immortals — to safeguard the primacy of the Communist Party by putting their families in charge of opening up China’s economy... Three children alone — including Deng’s son-in-law He Ping and Chen Yuan, the son of Mao Zedong’s economic czar Chen Yun — led or still run state-owned companies that had combined assets of about $1.6 trillion in 2011, or the equivalent of more than a fifth of China’s annual economic output.”

I have mentioned that the US, UK and Canada are all reaching historic levels of inequality. Many critics don’t see this as a problem. Some will point at stats that group populations into “quintiles” of 20% and point out that income differences are not that great. Others will argue that even if the top 1% or 10% are doing much better, it makes no difference because many items in an economists’ “basket of goods” have dropped in price, and as long as there is still upward mobility and opportunity, it doesn’t matter. Others will concede that inequality exists, don’t see why it is a problem, or why it should be addressed, or whether it has anything to do with the economy.

Growing inequality does matter, not just as a matter of fairness or “social justice” but because it is bad for the economy and for societies as a whole, including business.

What zealots are demanding as a free market economy, left to its own devices, are business practices that are not subject to regulations or the law. With no constraint on fraud, theft, lies and scams, markets will not self-correct, will not self-regulate, and will not distribute wealth as free-marketers claim. There is no reason to think it will, because it never has.

The only way it will work is if people have an open and democratic government, the rule of of law and some kind of plan to replenish the economy. Otherwise, we have the economic equivalent of a plague of locusts.

That’s why “moderation” and a government willing to smooth out the business cycle and put people to work is essnetial to shared prosperity and a level playing field - so that people can actually compete.

While there is demographic discrimination, it has to be said that there is also a direct impact geographically, which means that sparsely-populated rural and remote areas (which, worldwide, tend to be conservative) will be higher cost to services than densely-populated wealthier cities.

Businesses competing with each other for the 20% of the population with most of the money could actually make it cheaper to be rich, while the smaller number of businesses who provide services to customers who are remote, rural or low-income, can (and do) effectively charge a premium for goods and services to the poor.

This is most blatantly obvious with borrowing: if you have lots of money, you can borrow at good terms and low interest rates, and if you have little money, you pay more.

If a society is already unequal, the market, left to itself, will make inequality worse. That is why there is actually a lot more to the economy and the market than purely economic interactions. The market has never been the only way we value people, and it has never been the only link that defines the bonds between human beings.

This is why it is so important that recognizing the fundamental dignity and equality of human beings is enshrined in constitutions and bills of rights.

When people praise the private sector for its successes, cheerleaders gloss over the failures, which are considerable and constant. Treating the market as infallible is to look at only one side of the balance sheet — the revenue — without looking at the costs, especially the write-offs.

When a business fails, and go bankrupt, employees, shareholders and creditors may all be paid back pennies on the dollar, or nothing at all. Not only is this cost generally ignored, it is actually treated as a necessary positive: “creative destruction.” of clearing away deadwood in favour of new growth. It is critical to emphasize that corporations in particular are shielded from the full consequences of their failure by many legal mechanisms — limited liability, bankruptcy restructuring and more — that allow businesses to avoid the costs and consequences of their failure, which is often borne by others.

Sorting Customers

People’s thinking about business are usually from one of three points of view:

the point of view of management dealing with employees

the point of view of labour, bargaining with management or dealing with bosses

the point of view of the customer picking and choosing a product.

“If you’re going fishing, go where the fish are,” the saying goes. If 80% of money is concentrated in the hands of the 20%, it makes business sense to “segment” your customers. One way of doing it is in terms of income, or age, or some other demographic profile, density and geographic location.

For a business with fixed costs in terms of overhead and labour, this is important. The more customer traffic, the better, because employees are kept busy all the time selling the product. The opposite is true in less densely populated areas, including rural areas and small towns. There is more “down time” where employees are being paid but not serving customers.

For rural and remote areas, it costs more to deliver the product or service due to transportation costs. This is also the case with extending infrastructure — like electric power, phone, or cell-phone networks — over great distances to a small number of customers.

A large company may be able to serve rural and remote customers, or customers in poor areas, and still be profitable overall. But if they analyze their numbers, they will see that certain branches or lines of business are less profitable, or that investments in new infrastructure in some areas will take much longer to pay back than others.

Though other parts of a network may be highly profitable (in densely populated urban centres, or in a wealthy suburb), the cost of providing the service to that small of a customer base may actually cost money — or not be profitable enough to warrant services at that particular location.

So, low-income areas and rural areas get even worse service, or get cut off. It’s not economical to provide services there, and, as businesses often say, they are not charities. It becomes a vicious circle — amenities are shut down and cut off. Banks branches are closed and replaced by payday loan companies or pawn shops.

Pursuing an 80/20 strategy makes business sense, but it also “amplifies” the difference between urban and rural, and rich and poor neighbourhoods. Businesses will actively avoid providing services to rural and low-income areas, and compete to provide services in urban and wealthy areas. It’s explains the phenomenon of urban “food deserts,” where major chain groceries close down or avoid neighbourhoods or even cities.

This creates a vicious circle in rural and poor areas, and a virtuous circle (some might say bubble) in urban areas. When banks, post offices, pharmacies and grocery stores close down in a given area, residents have travel to get them, which means their money leaves the community, impoverishing it further.

A lot of how-to management and business writing is focused on the cost side of the equation: how to get more out of your employees through management, leadership, incentives, efficiency experts, motivation, investment in technology (or lower wages) and so on.

Much less ink is spilled on the revenue side of the equation. The 80/20 rule says that 80% of your revenue is going to come from 20% of your customers. It might be that they make a small number of high-dollar purchases, or that they are “loyal” and spend very frequently.

This is one of the key reasons that private enterprise succeeds: sorting. 80/20 is about how business looks at customers. Many economic theories are similarly blinkered: they take an accountant’s-eye view and are focused mostly on the internal workings of the company.

It should also be said that businesses are now using "surveillance” of your personal data in order to pre-sort you. When you call a bank and let them know who you are, how long you wait on hold and your customer service will be shaped by how “good” of a customer you are.

It also has much more serious implications: companies are using software to communicate about raising rents, or scanning people’s medical or other files/

It is a “kiss up, kick down” economic strategy that entrenches social stratification, it impedes risk taking and growth, because it denies opportunities for people in rural areas or poor areas access to opportunities that would enable them to take risks or build more prosperous lives. For example, access to electrical power, internet, health care, phone service or transportation as well as services.

What about Wal-Mart?

There will be people who say, “well, what about Wal-Mart?” and other giants, who serve enormous populations who are part of the 80%. Part of the answer is that companies who serve the “80%” are often benefiting from government social safety nets.

Because of the Global Financial Crisis, between 2007 and 2011, the amount spent on food stamps in the U.S. doubled to $75.7 billion. The recipients get food, but the money is, of course, all spent at grocery stores.

Tulsa World reporters studied food stamp data for Oklahoma and found that “Much of the nearly $1.2 billion in food stamp expenditures went to Walmart stores, which brought in about $506 million between July 2009 and March 2011, according to data supplied by the Oklahoma Department of Human Services.” Wal-Mart and other stores had to change their hours and shelf-stocking procedures in order to adapt to the fact that food-stamp recipients cards were charged up at midnight, resulting in line-ups outside stores.

This is true far beyond Oklahoma: Leslie Dach, Executive VP of Corporate Affairs for Walmart said that “A very significant percentage of all SNAP dollars are spent in Walmart stores, in some states up to fifty percent.”

In Sept, 2012, the incoming CEO of Kraft told the Financial Times that “one-sixth of Kraft’s revenues comes from food stamp purchases and that the portion of sales through the programme was probably larger.”

In Ohio alone, over 12,000 Wal-Mart employees received food stamp and medicare benefits in 2009.

On the one hand, a program like food stamps allows people who are out of work to feed their families. The financial benefit they receive will, literally, pass through their hands and be consumed — it’s impossible for them to save it, or build up any kind of a surplus that they can use to build wealth (which as people on assistance, no one expects them to do). But the company selling the product still makes a profit. In 2013, Kraft was #151 on the Fortune 500 list with $18.3 billion in revenue. Walmart, with $469.2 billion in revenue was #1.

What can we do when even a food stamp program appears to make inequality worse, even as it alleviates poverty and feeds those most in need?

Lower wages and higher unemployment are a consequence of both government and business following an “80/20” type approach. It treats employees as costs to be cut instead of assets to be maximized. But just looking at what is good for the supply side of business ignores that every employee is also a customer. If every business in town cuts their employees’ wages and hours, they will all have less money to spend as customers. This is known as the “paradox of thrift” and it is why the “race to the bottom” is ultimately self-defeating.

We are all the 47%

During the 2012 Presidential campaign, a videotape of a speech Republican Candidate Mitt Romney made to wealthy donors surfaced, in which he said:

“There are 47 percent of the people who will vote for the president no matter what. All right, there are 47 percent who are with him, who are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe that government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you name it. That that's an entitlement. And the government should give it to them. And they will vote for this president no matter what. And I mean, the president starts off with 48, 49, 48—he starts off with a huge number. These are people who pay no income tax. Forty-seven percent of Americans pay no income tax.”

In the world of politics, it is often hard to know whether politicians believe what they are saying. Romney’s comments seemed to suggest that 47% of the U.S. population were not working while receiving “free” health care, food and housing at the expense of everyone else. This is wrong.

There are two important questions here: who pays, and who benefits? Answering those questions can tell us quite a bit about government and the economy as a whole, and not just in the U.S.

Who Pays?

Where does the number 47% come from? In any jurisdiction, different levels of government levy different taxes. Some politicians will say, “there is only one taxpayer” to remind themselves or the media that a single person has to pay many taxes. Romney turned this idea on its head by implying there is only one tax: U.S. federal income taxes. When payroll and other taxes are factored in, the number of people not paying taxes shrinks to 17% and could be lower if excise taxes were included.

The 47% figure is from one year, 2009, a year that The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) said the figure was an anomaly, not just because of skyrocketing unemployment, but specifically due to a temporary tax break introduced specifically to help people cope with the financial collapse:

“The figures for 2009 are particularly anomalous; in that year, temporary tax cuts that the 2009 Recovery Act created — including the “Making Work Pay” tax credit and an exclusion from tax of the first $2,400 in unemployment benefits — were in effect and removed millions of Americans from the federal income tax rolls. Both of these temporary tax measures have since expired.

In 2007, before the economy turned down, 40 percent of households did not owe federal income tax. This figure more closely reflects the percentage that do not owe income tax in normal economic times.

So, three fifths of the 47% were actually working, but made less than $20,000 a year. They just didn’t make enough money to pass the threshold for tax payment, in part due to the “Earned Income Tax Credit” (EITC), which was first passed in the 1980s under the Reagan administration and expanded under George W. Bush. It was a policy pushed by political conservatives to alleviate poverty. When Bush passed the bill in 2004, he said “Nearly 5 million taxpayers will be off the rolls as a result of the tax relief this year.”

As the CBPP reported “Low-income households as a group do, in fact, pay federal taxes. Congressional Budget Office data show that the poorest fifth of households paid an average of 4.0 percent of their incomes in federal taxes in 2007, the latest year for which these data are available — not an insignificant amount given how modest these households’ incomes are; the poorest fifth of households had average income of $18,400 in 2007.[6] The next-to-the bottom fifth — those with incomes between $20,500 and $34,300 in 2007 — paid an average of 10.6 percent of their incomes in federal taxes.”

In comparison, Romney himself paid a 14.1% effective tax rate on an income of over $13.7 million in 2011.

The 47% also included:

over 7,000 people with incomes over $1-million

22,000 people with incomes between $500,000 and $1-million, and

81,000 people with incomes between $200,000 and $500,000.

So those are the facts, which because they are dry, abstract and involve large numbers that people can’t visualize, people will fail to engage with them. Sometimes when dealing with numbers of people, it’s useful to group them into units that can be seized on. Imagine, for example, an entire small town of 7,000 where every single person made over $1-million, is receiving benefits and paid no taxes or an 81,000-seat stadium at capacity with a cheering crowd of people, all of whom made between $200,000 and $500,000, none of whom paid income tax.

The people who support the basic premise of Romney’s 47% remarks are operating on the assumption that half of all Americans were getting something for nothing, and the other half were paying for it through their taxes. It is the idea that there are “makers and takers” and the makers are all self-reliant Republicans and the takers are all government dependent Democrats. This idea is not just confined to the top commenters on “the bottom half of the internet” it is repeated by high profile conservative “thinkers”.

There are two huge mistakes: one is the mistaken idea that because a person not paying taxes right now, they are not contributing to the economy. The statistic is a snapshot in time: it doesn’t consider that much of the 47% are made up seniors (who spent a lifetime paying taxes); students (who by earning an education will be able to make a better salary, contribute more to the economy, and pay higher taxes in their future) and 3/5 are actually working and contributing to the economy but don’t earn enough to pay taxes — at jobs whose low wages allow the companies they work for to make a handsome profit, especially fast-food, retail and service industries. These low wage workers often work at the type of companies Mitt Romney helped build at Bain Capital: mega-chains of big-box and strip-mall franchises like Domino’s Pizza and Staples, or places like Wal-Mart, whose heirs have a personal wealth equal to that of more than half the U.S. population — (though that is in part because a huge percentage of the population has no wealth at all.)

The low-wage workers in the 47% are contributing to the economy through work and through taxes, and they are paying other kinds of taxes, just not U.S. federal income taxes.

Who benefits from government spending?

The other misconception baked into Romney’s statement is that the only people who benefit from government are the ones who receive assistance in the form of some kind of cheque. Another one of the comments Romney made in his speech was that “95 percent of life is set up for you if you're born in this country,” the epiphany he came to after visiting a Chinese factory surrounded by barbed wire fences and armed guards that Bain was looking into buying.

This only gives a kind of vague sense of the opportunity that is involved in being born into a developed nation. Clean water, sewers and roads (all of which existed in the Roman Empire) make life better for everyone. Having a public water system means you, your family and your employees are less likely to get sick or die. Contrast this with the rest of the world: a 2004 World Health Organization (WHO) report said that 1.8 million people a year die from unclean water.

Transportation infrastructure — whether it is a Roman road or a railroad — lowers the cost of moving goods and people, opening up new opportunities for work and for trade.

Public investments improve and create private opportunity. By collecting taxes and using them to build permanent — or at least durable — structures that lower risk for society as a whole, government helps build wealth for everyone — especially those who succeed in business in that environment. One of the beneficiaries of the construction of the U.S. interstate highway system in the 1950s were American car companies: without roads, cars have nowhere to go, so there it no reason to buy them. In contrast, observers have long puzzled why The Aztec civilization never “invented” the wheel for transport when they has highly developed architecture, calendars, mathematics, trade, art and poetry. One obvious solution may be that the wheeled cart is not well suited to mountainous terrain and steep inclines: the technology of the wheel depends on the development of roads.

These public expenditures that lower costs and risk for everyone benefit everyone in a society, whether they pay taxes or not. People tend to focus on the expense of such projects, as if the only people who are benefiting from a water chlorination plant are the people being paid to build it, while ignoring the benefits that literally accrue to the whole population because they can drink clean water. Basic research and development (like a scientific or medical discovery) and education also provide private benefit at some public expense.

In places that have universal health care, treating people who are sick or preventing them from dying means they may live to have many more years of productive life. Why do people who favour low taxes and small government not see that?

One answer they don’t is that the benefit is hidden because it is preventive: it is stopping something from being worse than it could be, or because the cost is “buried.” Public health programs and vaccination face the same problem and skepticism: few people today remember the threat of polio or smallpox. They don’t know what they have been spared, just as people don’t consider how much harder life would be (and how much poorer everyone would be) without roads, bridges, clean water, a functioning sewer system and public schools.

One could point to the developing world, where people are sick, poor and dying for those exact reasons. But when we make that comparison, instead of realizing that a strong government is part of the reason we are rich and others are not, the response is to blame people for the situation they’re in, rather than seeing that the situation they’re in accounts for why they’re poor.

How the (American) Wealthy Got that Way (2011 edition)

The quintessential American story is the rags-to-riches tale of talent and entrepreneurship — the scrappy immigrant who builds an empire, the inventors who start in a garage and end up with the biggest company in the world, thanks to hard work, skill, and smarts, claw their way to the top.

There is also an inverse belief at work — that if someone is wealthy, they must be smart and talented. When we consider the 20 wealthiest people in the U.S. from the Forbes 2011 Top 100 List, they are an interesting mix of people who fulfill the idea of self-made billionaire entrepreneurs, investors, and heirs. The entrepreneurs in the top 20 are almost all tech billionaires — Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer of Microsoft, Larry Ellison of Oracle Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Sergey Brin and Larry Page of Google, Michael Dell of Dell. The investors are Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway, George Soros, John Paulson. Then their are the heirs: Jim, Alice and S. Robson Walton (heirs to Wal-Mart); Charles and David Koch, (heirs to Koch Industries) and Jacqueline and John Mars (the Mars Candy company). Rounding out the top 20 were Michael Bloomberg, who owns a business media empire, and Sheldon Adelson, a Las Vegas Casino magnate.

Even in the 2011 Top 100 list, wealth is tilted heavily toward the top, though not 80/20. At number one on the list with $59-billion, Microsoft’s Bill Gates is worth 20 times more than # 100 on the list, Discount Tire’s Bruce Halle, worth $3-billion. The top 20% are worth $445 billion, while the bottom 80% are worth $507-billion. The actual ratio for the top 100 billionaires in the U.S. is more egalitarian than the rest of society: 60/40, with 60% of the wealth in the hands of the top 40%.

Many of the companies in the top 20 list, especially tech companies, succeeded by being profoundly disruptive: Microsoft is one of the few on the list that even existed in 1980 — or 1990. They are at the heart of a technological revolution that is having a profound effect on the economy. These companies have grown by displacing many other products, companies and jobs. Entire range of industries whose products could be digitized and transmitted by internet — music, news, books, video, films, as well as the entire infrastructure that once existed to make those products and move them to brick-and-mortar stores to be sold.

If you’re wondering whether this way of running things is sustainable, it’s not, But that does not mean permanent “collapse”. However it is not something that the market or private actors can achieve on their own.

The actual history of government involvement in the economy, especially in the U.S., is completely denied or ignored. Republican Theodore Roosevelt challenged monopolies, Democrat Franklin D Roosevelt brought in the New Deal, which introduced new laws and regulations as well injecting new equity into the U.S. economy for the purpose of economic and industrial development.

The concentration of wealth is because we have seen more and more consolidations and mergers over the years, which has led to more monopolies and more competition.

As I’ve argued, we need is a Marshall Plan and a New Deal, and measures to increase competition, not just by breaking up existing monopolies and oligopolies, but by providing access to capital for real economy start-ups and scale-ups, with access to equity investments, not debt.

Wealthy countries became wealthy because they had governments that were large enough and made investments in infrastructure, but also because governments make markets possible.

Without property rights, laws to settle and enforce contracts, laws to preserve and register intellectual property, investments in transportation, water and energy infrastructure, and legislation that created the framework for corporations and other forms of organization, there would be no “private sector” and no market of any kind.

Warren Buffett said

“Buffett has no hesitations in acknowledging the role historical circumstances have played in his success. The United States with an economy of about US $15-trillion and a stock market with a capitalization even larger than that provides him with an almost endless landscape to search for sound investments. “I personally think that society is responsible for a very significant percentage of what I have earned. If you stick me down in the middle of Bangladesh or Peru or someplace, you’ll find out how much this talent is going to produce in the wrong kind of soil. I will be struggling 30 years later.”

And above all, there needs to be a commitment to the rule of law and the defense and protection of individual rights in a landscape of changing technological and social change.

In this, only government can make the decisive difference, to defend the freedom of the individual not just against an overbearing state, but also to protect the state against capture. The private sector can only act in the private interest. Only the public sector can act in the public interest, as constitutions spell out and make it clear.

-30-

DFL

I first heard of the Pareto principle in some Jordan Peterson video that my friends thought explained how nature works applied to humanity.

Turns out it's a self fulfilling prophecy.

But look at how shitty it works!

I used to think that Peterson was an asshole, but now I see that he's the guy that's so dumb that he believes in the pyramid scheme that we all know is total bullshit.

Love this breakdown of the Pareto principle. I remember seeing that 80:20 book handed to people being groomed for management and then hearing them describe the theory as mathematical fact. People who consider themselves good Christians that attend church more than once per week have no problem believing that wealth distribution is some kind of natural law so long as a book backs up their notion.