Canada's Provinces Run the Country. Why do we pretend they don't?

Canada has one of the least powerful federal governments in the world, which means that, for good or bad, citizens are much more affected by their local government. Why is that ignored?

It’s sometimes said that “Canada is one of the most decentralized governments in the world.” Another - simpler - way of putting it is that Canada’s provinces are among the most powerful of any country in the world and this is reflected in their budgets as well as their spending.

Not only do the provinces have many more expensive responsibilities, their total combined expenditures are much larger than the Federal Government’s as well. While there are a few areas of federal and provincial overlap, most of the arguments in Canada are either about the federal government taxing too much, or provinces not getting enough funding.

The basic political narrative we hear in Canada, is that everything is the federal government’s fault, or the Prime Minister of the day, whether it’s Justin Trudeau or Stephen Harper.

I am going to pick a pre pandemic year so it’s not a year where we’re dealing a crisis, and, I won’t lie, because these are the numbers that were on Wikipedia - but all the data is derived from government budget documents - planned budgets - not actuals.

This puts some of the economic footprint of provinces and big cities in perspective: the City of Toronto, the capital of Ontario and the largest city in Canada, has a larger budget, at $16.997-billion, than six out of ten provinces.

The expenditures are largely an issue of population. It takes more revenue to pay for the services to a lot of people than a few people.

The revenues are usually due to one of three things - natural energy resources like oil, natural gas and mining, (BC, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Newfoundland); finance (Toronto and Ontario) and - to some extent - real estate speculation (Vancouver and Toronto).

There’s an important asterisk to this chart, which also applies when we look at the Canadian government. You can’t just add up all this spending, because some of it you will be counting twice.

In Canada, the federal government has transfer payments to the provinces, and the provinces transfer money to cities and municipalities. So in the chart above, some of the provincial budgets are actually transfers that go to cities.

In 2018-19, the Government of Canada’s budget was $338.5-billion, about half - 50% is going straight to individual Canadians as benefits, or straight to provincial governments as transfer payments.

The point here is that people look at a government budget and they think it is somehow spent “in” that government when it is spent “out” - $71.8 billion of the federal budget goes to provinces, who are supposed to apply the Canadian health transfer for health and social programs.

Seniors’ benefits are $53.6-billion.

Employment Insurance benefits are $20.7-billion

Children’s Benefits $23.7-billion.

Together, these add up to $98-billion in benefits for Seniors, people who are unemployed, and families and children.

The Canada Health Transfer is $38.6-billion. Health transfers go to every province, on a per capita basis.

The Canada Social Transfer is $14.2-billion. These transfers also go to every province.

Equalization Payments: $19-billion. Equalization goes as a “top-up,” with some provinces getting more and some getting none. It’s supposed to be to ensure provinces can provide comparable levels of service that the smaller provinces with smaller economies would otherwise have to sharply raise taxes to pay for.

The total of these transfers to provinces is $71.8-billion. (There are also transfers to territories, but I am focusing on provinces).

30% of the federal budget goes to support seniors and children and the unemployed. The one thing they all have in common is that they are not working, which is to be expected from the elderly, children and the unemployed.

Another 20% goes to provincial governments. Because cities and municipalities are legal “creatures” of the provinces, the federal government is not supposed to fund them directly - the funds are supposed to go to the provinces.

The point here is that we don’t want to count the same dollar as being spent “twice” when dollars are being shifted from the federal government to the provinces, who actually allocate the funds.

If you compare the size of the federal government’s spending on its own areas of jurisdiction, the combined fiscal footprint of provincial governments is much more than the federal government.

In fact, a Scotiabank analysis of recent inflation suggested it was the provinces - not the federal government who were playing a greater role in inflation than the Federal Government.

It’s not just what they spend: provinces and municipalities “own and maintain the majority of public infrastructure.”

Jurisdiction: Whose Job is It?

When we talk about a government’s jurisdiction, it means that it is legally bound, by the constitution and other legislation, to only spend money on certain things - and only they can spend it.

In Canada, the provinces, have an enormous number of serious and costly responsibilities that include the regulation and programs that affect every single resident’s life on a daily basis, from their birth certificate, through their marriage certificate to their death certificate and everything between.

In Canada, provincial governments have jurisdiction over:

Vital statistics - birth, death and marriage certificates.

Health care - each province has its own public health insurance system, with different coverage in each one. Pays for hospitals, doctors, nurses, medications, homeware and more.

Education - curriculum, teacher certification, post-secondary education - funding for infrastructure.

Child and family services

Land titles, property rights, property registration

The environment and natural resources - water, lakes and rivers, fish and wildlife, oil, gas, mining, including permits, approvals, and revenue from royalties.

Cities - each municipality, whether it’s rural or it is a city, is created through provincial legislation. The province can change anything they want about how a city is run, or the way they levy taxes.

The enforcement and administration of justice: courts, jails. Provinces run provincial courts, and have provincial jails for sentences of two years less a day.

Business and corporate registration and labour and workplace safety, including the workers compensation board

Regulating professions, including doctors, nurses, engineers and others.

Human rights

Roads and public infrastructure (bridges) highways and drivers’ registration

Alcohol and cannabis regulation

Securities regulation.

In some provinces, governments own “Crown Corporations” which are government owned and run (at arm’s length) corporations, including monopolies on alcohol sales (Manitoba, Ontario, others) telephone systems (Saskatchewan), Hydro-electric power (for example, BC, Manitoba, Newfoundland), auto insurance (Manitoba) and in some cases Uranium companies (Saskatchewan) and potash companies.

Part of Canada’s fundamental challenge is that because the provinces ended up getting the expensive programs without adequate revenue tools to pay for it.

In 1867, when they were distributing these rights, there was no modern medicine, and there was no compulsory schooling. No one could imagine what the future achievements of advancements in health care and public education would occupy such a huge part of future budgets: but that’s the price of saving lives and investing in an educated population to drive our shared prosperity.

The other, is that over the years, provincial governments have simply taken to blaming the federal government for everything, when they play a much larger responsibility for most of the most serious decisions affecting citizens’ lives - life and death decisions around health care, income assistance, and administering justice. It’s the old saying “Before they point out the speck of dust in someone else’s eye, they should consider taking the plank of lumber out of their own.

This dodge may be seen either as a lack of personal and professional responsibility on the part of politicians, or a clever bit of political strategy and communications sleight of hand.

However, it has real consequences for whether the country is “broken” or not and how it can be fixed.

Issues of jurisdiction mean that the only level of government that can fix the problem is the one that is responsible for it.

This means that if provinces get funding and refuse to spend it on on health care, or social assistance, or investing in innovation or new business growth, there is very little the federal government can do about it.

In 1867, when Canada was founded, Upper Canada (Ontario) was largely British and protestant, and Lower Canada (Quebec) was largely French and Catholic. One of the reasons for education being a provincial responsibility, not a national one, was to ensure that there would be French schools in Quebec. Health was also largely a provincial responsibility. (The Federal Government is responsible for First Nations and Inuit Health care, as well as the health care for the armed forces.)

The federal government’s basic responsibilities relate to First Nations, borders and how we maintain them - citizenship, immigration, passports, national defence, seas and oceans, and issues that cross provincial borders. So railways and pipelines are federally regulated, but only if they cross provincial borders. So a number of “networked” industries in Canada are regulated federally - telecommunications - including radio, television and the internet; transportation, like railways, aerospace, banking, pharmaceuticals and federal corporations.

One major difference between the Government of Canada and the United States is that the criminal law in Canada is set by the Federal government. The criminal law is the same in every province in Canada.

The provinces - which are responsible for the administration of justice, but are limited in what they can do.

The other thing the federal government can do is to make payments directly to individuals, which it does through pension programs and the Canada Child Benefit.

The Cynical Politics Behind the “Blame Game”

In Canada, after the Liberal government was elected in 2015, the federal government increased funding to the provinces, both in the form of equalization payments, as well as new funds for health care, housing, infrastructure and more.

Shortly thereafter, a number of Conservative governments were elected (or re-elected) at the provincial level, and most of them adopted a similar strategy: they did not spend the transfers they received on either health or infrastructure.

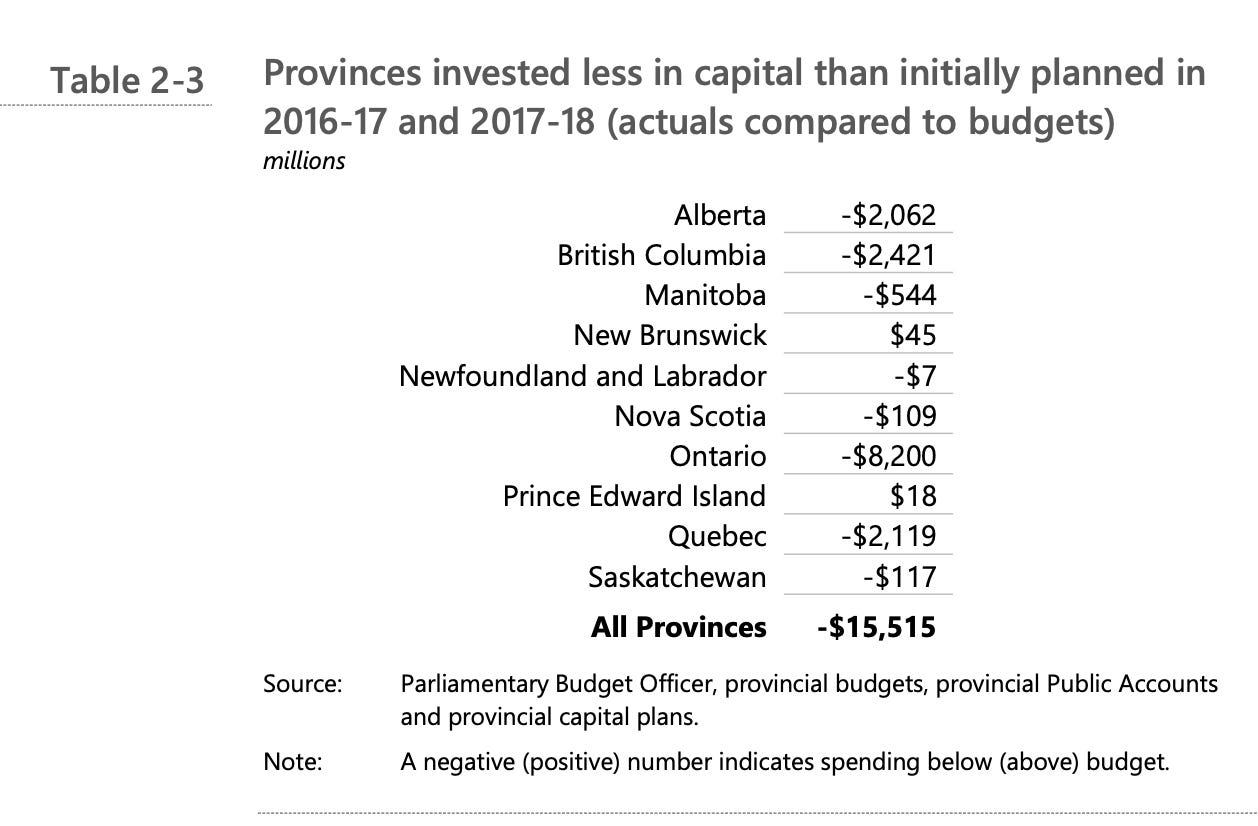

This was reflected in a report by the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) in Canada, which showed that provinces were not spending the money they were getting.

The PBO seemed to express some puzzlement, because the reason was not clear.

One argument could be that many provinces were taking the opportunity to shore up their finances because they had been running deficits, in part because of the Federal Conservative governments efforts to balance the budget prior to the 2015 election, which involved deeply restricting transfers.

But there was something else at work.

“The Investing in Canada Plan (IICP) is the 12-year, $188 billion, infrastructure investment plan introduced in 2016 by the Government of Canada. The IICP is being delivered in two phases between 2016-17 and 2027-28: Phase 1 for short-term infrastructure needs during the first two years, and Phase 2 starting in 2018-19 for longer-term investments.

Our results point to a clear difference between provinces and municipalities with regards to the impact of the IICP on capital investments. It appears the IICP has contributed to increase municipal capital spending, but not provincial capital spending. Our main findings are as follows.

Provincial capital spending has been below budget since the start of the IICP. Based on PBO’s calculations, provincial capital spending was $3.8 billion lower than what it would have been in the absence of the IICP.

Provincial capital spending was also $5.4 billion lower than what it should have been after accounting for additional infrastructure funding delivered through the IICP. This spending gap suggests that funding from the federal government probably displaced provincial investments after the IICP began. Another possibility is that provincial governments postponed or cancelled capital investments after the start of the IICP.

Had provincial governments kept capital investments in line with PBO’s post-IICP benchmark, real GDP could have grown between 0.15% and 0.16% in 2016-17, while employment level could have increased in the range of 7,550 to 8,100 jobs.

In contrast to provinces, capital investment was higher than budgeted in the municipalities selected for review. In 2017 and 2018, actual municipal spending on capital was $1.0 billion higher than what it would have been in the absence of the IICP (Figure 3-1).

Some, like Manitoba, dragged their heels on signing the agreements at all, and even after signing them, refused to spend.

The same month that the PBO report came out - March 2019 - the Government of the province of Manitoba, was sitting on $1.9-billion in unspent federal funds:

$400-million health fund for mental health and homecare

$400-million for new housing

$500-million in funding for transit

$600-million in infrastructure

There is an important point here about infrastructure investments, they provide immediate short-term jobs and revenue as well as paying back over the long term.

Instead of balancing their budgets and investing the transfers and increased equalization for what they were intended - health care, social services, provinces like Manitoba used the extra new funding from the federal government to reduce taxes (usually for the highest income earners), while freezing or cutting health care, even and costs were growing.

This was blamed - very publicly - on the federal government. The provinces and provincial premiers launched a campaign that falsely suggested that health care funding was being cut by the federal government.

It was bizarro-world communications: provincial premiers who actually cut health care, successfully blamed the federal government.

What’s happening is that Canadian conservatives have taken a page from their US counterparts.

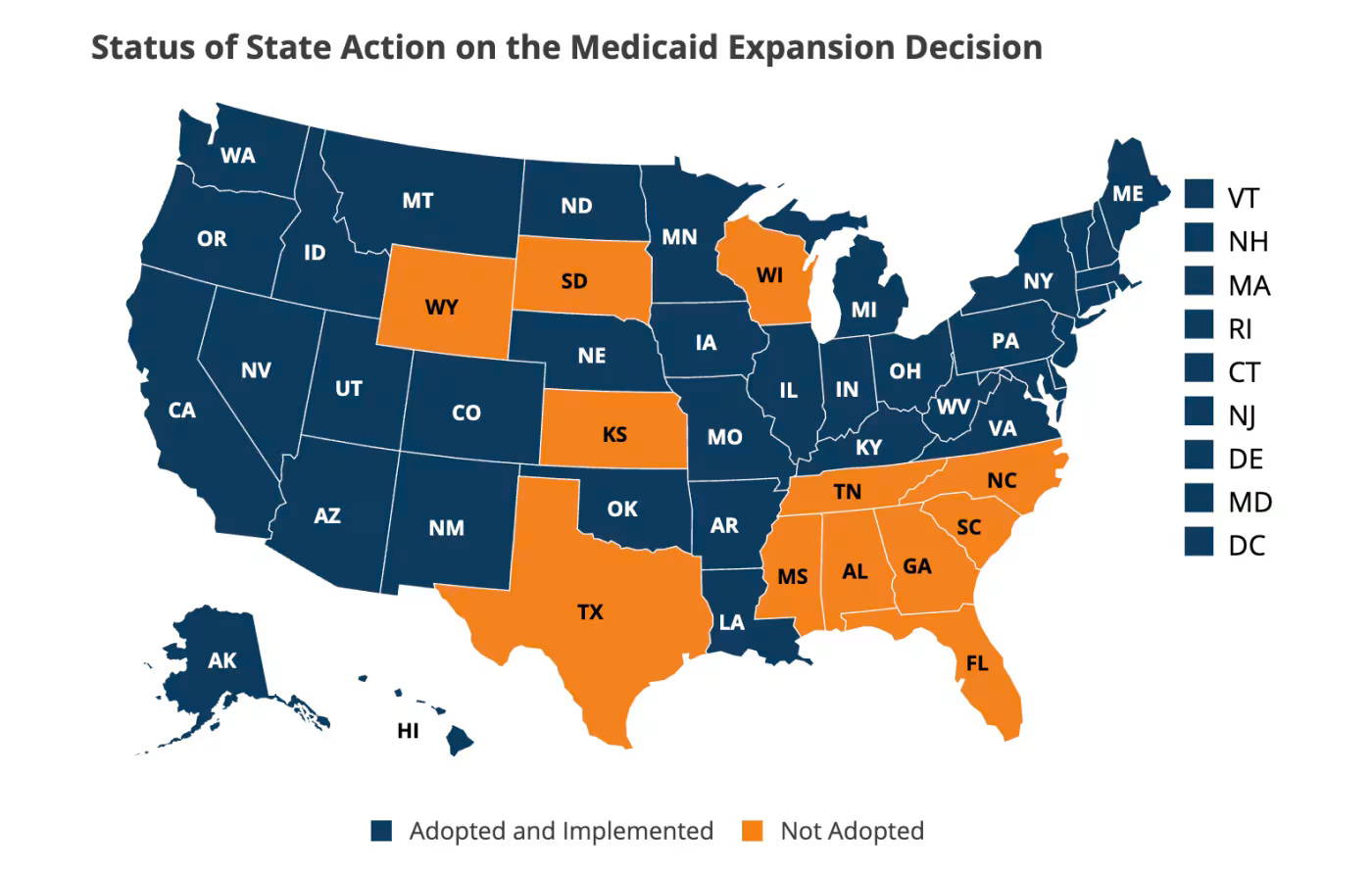

It can be argued - persuasively - that provincial premiers are doing what their U.S. republican counterparts in Republican-run states are doing: denying their own residents health care and infrastructure investments in order to increase their distress and suffering, then blaming the federal government for it.

As of 2021, 12 states in the U.S. refused to expand “Medicaid” - a federal government program designed to ensure that people with low incomes can get health care. These states are forgoing $49-billion US in order to deny their own citizens access to care.

In Canada, Provincial Conservative Governments have adopted the same tactic - going out of their way to deprive their own residents of services that would benefit them, with funds being offered by federal governments for that specific purpose - health care, housing, crime.

The Council of Federation, led by two Manitoba Premiers, then launched a national ad campaign on behalf of all provinces, that falsely implied that the federal government was cutting health care funding, when it was being increased.

In 1976, the Federal Government negotiated a new deal with provinces, which means that a chunk of the tax money the feds used to take, would go to the provinces instead. When that happened, the federal contribution of the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) appeared to drop, from 35% to roughly 25%, because the tax points were shifted, not because of a “cut.”

Since 1977, it has been between 25% and as low as 15%, but it was at 22% for some years. However, the CHT is not the only source of federal funding for health to the provinces, because equalization also plays a role.

Winston Churchill said I paraphrase) that “democracy can’t survive without accountability.”

What has happened in the last years in Canada is that provincial failures in areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction have been pinned on a federal government that has often stepped up while the provinces cut - to shift the blame and win elections for Conservatives at the Federal level.

And before you ask, “would a politician in office in Canada really go out of their way to deny someone health care or food, even though they have the funds?” the answer is that is what austerity does. And it’s happening in Canada, and in the U.S. again - From today’s New York Times: (Jan 12, 2024)

-30-