Big Week: European Central Bank President on Economists "a tribal clique" and Bank of Canada changes course

‘The track record of forecasting is abysmal’

This is a very important statement by Christine LaGarde, who was head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and is now the head of the European Central Bank.

At the World Economic Forum at Davos, LaGarde gave a speech denouncing economists and their models:

“Many economists are actually a tribal clique,” she said. “[They] are among the most tribal scientists that you can think of. They quote each other. They don’t go beyond that world. They feel comfortable in that world. And maybe models have something to do with it.”

“If we had more consultations with epidemiologists, if we had climate change scientists to help us with what’s coming up, if we were consulting a bit better with geologists, for instance, to properly appreciate what rare earths and resources are out there, I think we would be in a better position to actually understand these developments, project better, and be better economists.”

Lagarde has first-hand experience of the ways in which economists and their models have completely failed.

One of the most notable recent examples of this colossal failure was the mishandling of the economic crisis that struck Greece and other states in the European Union.

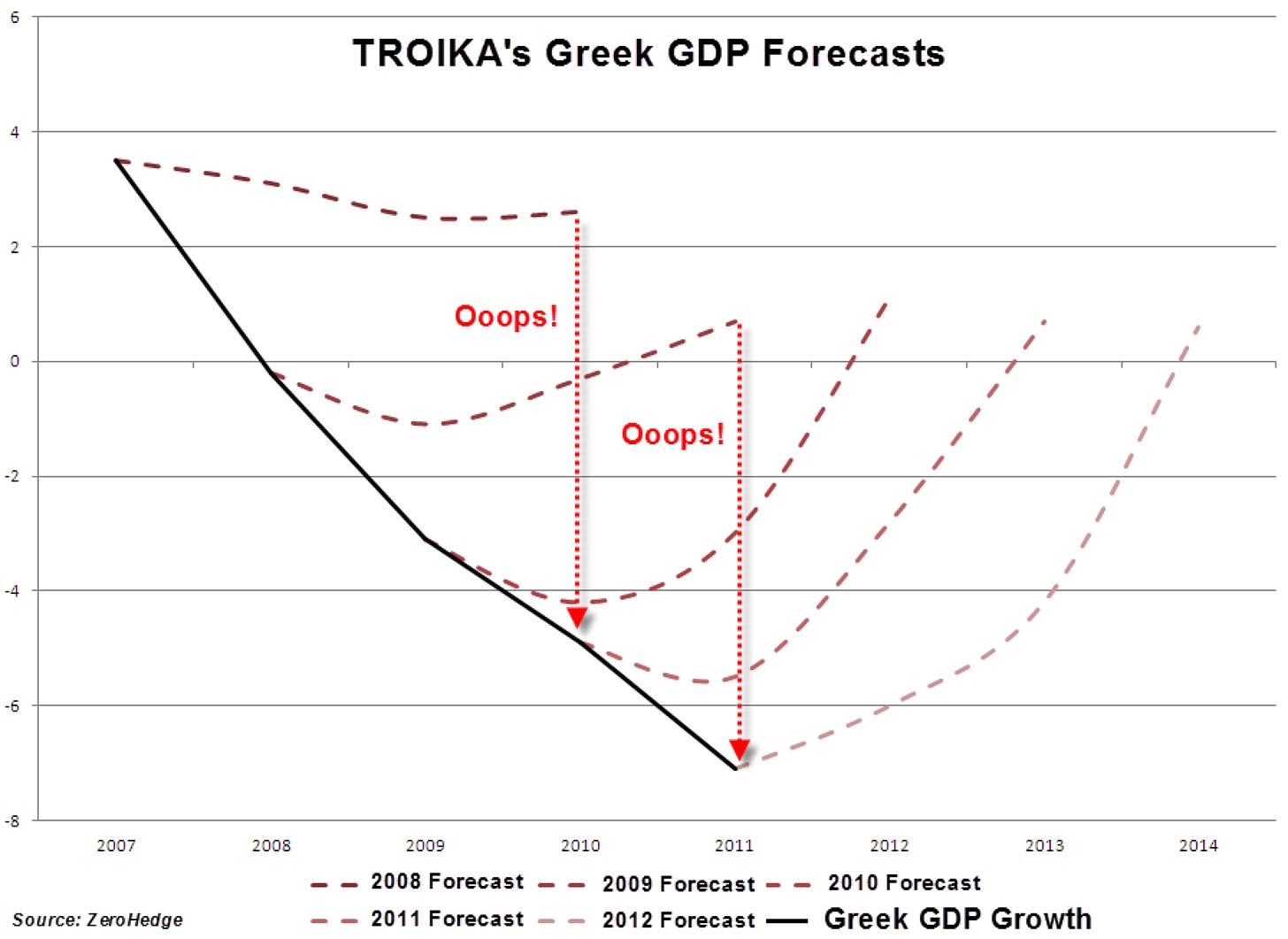

This is a chart showing the modelling projections for what austerity would do to Greece, and what actually happened - the “Troika” is the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund.

The dotted lines are the projection for recovery and growth, while the black line is the actual: five years straight of projections that failed.

The results were catastrophic. The Troika’s policies collapsed the Greek economy by over 30%. Adult unemployment hit 25%, while youth unemployment hit 50%.

By comparison, if the U.S. were to lose 30% of its GDP, it would be a loss of about $7-trillion in economic activity. In Canada, losing 30% of GDP would be a loss of $600-billion.

It is not an exaggeration to say people have died as a consequence. Suicide rates went up and poor seniors were eating out of the garbage.

Incredibly, from a fiscal point of view, Greece was a success, because in the midst of this, it was balancing its budget.

The hundreds of billions in bailout money for Greece? It never made it to the people. Between 60% and 95% of the bailout flowed straight back to its creditors - mostly banks in the UK, Germany and France, who had bought huge amounts of risky bonds from countries in the EU periphery - as well as Spanish mortgages and more.

The UK’s Telegraph reported that the IMF’s “top staff misled their own board, made a series of calamitous misjudgments in Greece, became euphoric cheerleaders for the Euro project, ignored warning signs of impending crisis, and collectively failed to grasp an elemental concept of currency theory.”

Lagarde is certainly not the only extremely high-profile individual to say that orthodox economists models don’t work.

“Eventually, evidence stops being relevant”

I keep returning to Paul Romer, who was the Chief Economist for the World Bank, who wrote a paper in 2016, “The Trouble With Macroeconomics” where he described “more than three decades of intellectual regress”:

Macro models now use incredible identifying assumptions to reach bewildering conclusions. To appreciate how strange these conclusions can be, consider this observation, from a paper published in 2010, by a leading macroeconomist:

... although in the interest of disclosure, I must admit that I am myself less than totally convinced of the importance of money outside the case of large inflations.

Romer describes leading macroeconomists who don’t think money matters, and who argue that “shocks” are “imaginary,” and can have no impact on the market. To do so, they quote Milton Freidman’s 1953 assertion that “the more significant the theory, the more unrealistic the assumptions.”

That phrase has no basis in reality - and as a result, neither does orthodox economics - something Romer finds appalling:

More recently, "all models are false" seems to have become the universal hand-wave for dismissing any fact that does not conform to the model that is the current favorite.

The noncommittal relationship with the truth revealed by these methodological evasions and the "less than totally convinced ..." dismissal of fact goes so far beyond post-modern irony that it deserves its own label. I suggest "post-real."

Romer - who actually understands the math inside and out - points out that many of the data points are imaginary.

Romer’s paper is inspired by a similar argument - “The trouble with physics” by Lee Smolin, an American physicist who teaches at Waterloo and the University of Toronto in Canada. Smolin argued that “string theorists” - is not viable.

Tremendous self-confidence

An unusually monolithic community

A sense of identification with the group akin to identification with a religious faith or political platform

A strong sense of the boundary between the group and other experts

A disregard for and disinterest in ideas, opinions, and work of experts who are not part of the group

A tendency to interpret evidence optimistically, to believe exaggerated or incomplete statements of results, and to disregard the possibility that the theory might be wrong

A lack of appreciation for the extent to which a research program ought to involve risk

He continues:

“developments in both string theory and post-real macroeconomics illustrate a general failure mode of a scientific field that relies on mathematical theory. The conditions for failure are present when a few talented researchers come to be respected for genuine contributions on the cutting edge of mathematical modeling. Admiration evolves into deference to these leaders. Deference leads to effort along the specific lines that the leaders recommend. Because guidance from authority can align the efforts of many researchers, conformity to the facts is no longer needed as a coordinating device. As a result, if facts disconfirm the officially sanctioned theoretical vision, they are subordinated. Eventually, evidence stops being relevant.”

That is why, when it comes to prediction, these models are a total failure.

Robert Lucas is one of the economists who came up with “post-real” economics delivered a 2003 lecture in which he claimed that his invention meant that economic crises and depressions had been eliminated.

“My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.”

In 2008-09 the Global Financial Crisis struck, proving Lucas to be wrong.

Yet - yet - nothing has changed.

There is a reason why the world is in crisis, why populists and authoritarians are surging, and why economists are completely blind to it: according to their own models, it can’t be happening.

In the U.S. and in Canada people cannot understand why people are so angry and desperate, because economists’ models deny that crises can happen - when the models themselves are causing them.

Lagarde’s intervention is more than welcome, and it is more than overdue.

In the last two decades, we have had a global financial crisis, a currency crisis in Europe, a shattering global pandemic, climate change and rising threats to democracy - all of which are ignored because the fundamental ideas at the heart of the economy are built around a clockwork economic model that keeps crushing people in its gears.

The Bank of Canada is Changing its Model

As I was writing this piece, the Globe and Mail published a story that the Bank of Canada is going to overhaul its models for the first time in two decades.

This is, I hope, positive. In the first post on this blog, I wrote that the single most important thing for Canada’s economy would be for the Bank of Canada to heed William White and change monetary policy.

If you want to see an example of predictions going wrong, here are examples of the Bank of Canada’s projections for what inflation would be over 18 months, where every single projection understated inflation.

It also plans to build a suite of additional models it calls satellites, which will act as a check on the main model’s assumptions, and a set of specialty models designed to address specific issues, such as financial stability risk or the economic impact of climate change.

If all goes to plan, these models will go live in mid-2025.

While there is lots to be seen, the positive is that the change is happening, and that it will address some of the fatally flawed parts of central bank modelling. For that reason, the fact that the models won’t go live until mid 2025 is a problem.

A very major problem, because central bank policy is terrible for the economy, right now. The Bank of Canada is bankrupting families and businesses in the name of fighting inflation. That should stop as soon as possible, not 18 months from now.

The good news is that:

The financial sector will be included.

It will consider distribution for business and households - recognizing that there are many different households being impacted in different ways.

Some totally inadequate models are being scrapped

There are two parts to the bad news.

First, when you understand how completely insane the central bank models are, it is shocking.

The Bank of Canada, which sets interest rates, did not and does not include the financial system in its models. Like almost everyone the Bank failed to predict the Global Financial crisis. One group of economists who did were post-Keynesians - who consider the role of personal and private debt and banking in destabilizing the economy.

For more than 40 years, the main job of the Bank of Canada has been to regulate the national economy with interest rates, and they did not include the financial sector in their calculations. The one industry to which interest rates matter more than any other: banks.

“They missed the boat on the financial stuff,” said Stephen Williamson, an economics professor at the University of Western Ontario. “They didn’t have that in their models.”

In the wake of the crisis, central banks, including the Bank of Canada, added more detail about housing markets and household debt into their models, and developed alternative tools to help monitor financial stability risks. But they still haven’t integrated the financial system into their models in a comprehensive way, Prof. Williamson said.

The understatement of just how important these failures are is mind-boggling.

Because ToTEM and LENS are both based on a rational expectations framework.. The virtual consumers and businesses inside the models basically trust the central bank to do its job and keep inflation at 2 per cent.

The “rational expectations” school of economics means that they assume that every single person has total and superhuman knowledge of the economy.

In his book Debunking Economics, Steve Keen wrote that Solow and Swan tried to build a model for the whole economy by scaling up microeconomics based on a "representative" consumer's tastes for goods and services, as well as preferences for leisure. Booms and busts would only happen because technology or preferences changed -

"This resulted in a model of the macroeconomy as a single consumer who lives forever, consuming the output of the entire economy, which is a single good produced in a single firm which he owns and in which he is the only employee, which pays him both profits equivalent to the marginal product of capital and a wage equivalent to the marginal product of labor, to which he decides how much labor to supply by solving a utility function that maximizes his utility over an infinite time horizon which he rationally expects and therefore correctly predicts... Any reduction in hours is a voluntary act, so the representative agent is never unemployed, he's just taking more leisure. And there are no banks, no debt and indeed no money in this model."

That explains the change, as reported in the Globe, that the model will actually recognize that different people own different amounts of property, and earn different salaries.

There’s also an increased emphasis on what economists call “heterogeneity.” Current models are built around a small number of representative agents: one household, one business and so on. But this fails to capture the fact that people spend, save and bargain for wages very differently depending on their wealth, location and other individual circumstances – and that these characteristics aren’t static.

Current monetary models are so basic that they make their calculations based as if the whole economy were one single person, or a single business. So there is no recognition that interest rates will have different impacts on different people. This is madness.

Mistakes

There are at least two quite serious errors in the Globe article, relating to the engineer and economist Bill Phillips, who came up with the “Phillips curve” which suggested there was a connection between inflation and employment.

The first error is historic - an incredibly important mistake that many people make - which is that the Phillips curve was part of John Maynard Keynes’ theories. It was not.

The Globe writes:

The Bank of Canada got into the model-building game in the 1960s, and has since gone through three generations. Early efforts were based on the ideas of British economist John Maynard Keynes and relied on mainframe computers. To run the web of equations, the bank had to send punch cards by bus to a computing centre at the Université de Montréal and transmit data by modem to a computer in Utah.

These models ran into trouble as inflation surged in the 1970s. The models assumed there was a stable trade-off between unemployment and inflation, given the connection between tight labour markets and wage growth. But this assumption meant the models couldn’t explain the combination of high unemployment and high inflation, known as stagflation, that took hold after the oil price shocks that decade.

The formula that failed in the 1970s was the “Phillips curve” because it had failed to predict stagflation.

The error is that the Phillips curve was part of Keynes’ theories or ideas. Keynes did not formally express his new ideas in mathematics. One of the key aspects of Keynes’ work was uncertainty, which can be a challenge to express in mathematical formulas.

However, as Steve Keen’s further analysis of orthodox macroeconomics showed, others stepped in, often just repurposing old ideas and formulas. Phillips was not doing that: he was a Keynesian, but his discovery of the Philips curve was his own: it was not a mathematical explanation of one of Keynes’ ideas.

It was the Phillips Curve that failed, not Keynes. Keeping in mind is failed under the strain of the U.S. going off the gold standard, Vietnam, a war in the Middle East, and the price of oil quadrupling.

The article also makes the mistake, as many do, of dismissing Bill Phillips, who was a technical and engineering genius and war hero who went into economics after the fact.

The Globe writes:

there were some more eccentric efforts, including a hydraulic model of the British economy, built by New Zealand economist Bill Phillips in 1949, which illustrated the movement of money throughout the economy with coloured liquid flowing through a series of tanks and pipes.

Phillips built the hydraulic computer as a student at the London School of Economics, and to belittling the construction of a functioning hydraulic analog computer as “eccentric” ignores the fact it worked, and that it immediately performed complex calculations.

In a world where there were no electronic computers available for such calculations - everything - there were no digital calculators, and complex calculations, from spreadsheets to calculus, had to be worked out by hand, by slide rule or by mechanical adding machine. The hydraulic computer immediately output accurate results with many different variables.

The invention should also be placed in the context of Phillips’ extraordinary life. As mentioned, he invented the hydraulic computer as a student, having already had an extraordinary life as an engineer. Phillips was an extraordinary individual. On a troopship fleeing Japanese fire, he improvised a machine gun mount so he could return fire.

He spend three and a half years in a Japanese Prisoner of war camp where he jerry rigged a miniature radio and a kettle to make tea that others said contributed enormously to morale, at the risk of his own life. Laurens Van Der Post was in the camp with him, and said he was one of the most remarkable men he had ever met.

Who pays when central banks make mistakes?

This is a serious question, and a challenging one, for the most important reasons, which is that institutions with the powers of a central bank have to be held to the highest standards of integrity in order to maintain their independence.

For that reason, we have very strict rules around Federal politicians and Ministers steering clear of directing anything the Bank of Canada can do.

The Bank of Canada is a public institutions that can make or break the economy. We have heard warnings that by criticizing it (including very badly, as some elected officials have done) that it is undermining the Bank’s independence.

We must be able to have a way to discuss and debate monetary theory and ideas without politicians directing the Bank of Canada. These are still human institutions. One of the things the Bank of Canada is doing is creating “satellite” offices that will operate as a way of critiquing itself.

This is what happened in the U.S. but some of the satellites actually pushed some of the worst ideas, like “rational expectations”

The real question is accountability for harm done by bad monetary policy. It needs to be more than “The strong do what they will; the weak suffer what they must,” which is what it has been for decades.

Changing Canada’s monetary policy is the single most important thing that can happen to make positive change happen in Canada’s economy. That’s what I wrote in the very first piece for this blog, where I quoted Edward Chancellor:

“By aggressively pursuing an inflation target of 2% and constantly living in horror of even the mildest form of deflation, they not only gave us the ultra-low interest rates with their unintended consequences in terms of the Everything Bubble. They also facilitated a misallocation of capital of epic proportions, they created an over-financialization of the economy and a rise in indebtedness. Putting all this together, they created and abetted an environment of low productivity growth.”

It wasn’t elected politicians or elected governments who “facilitated a misallocation of capital of epic proportions… created an over-financialization of the economy and a rise in indebtedness [and] created and abetted an environment of low productivity growth,” it was central banks.

We have financially engineered our way into this mess, and we can financially engineer our way out of it. And the Bank of Canada needs to consider its role in repairing the harm done - especially by excess debt created by bad monetary policy.

It is not enough to just say “We’re taking a new approach,” when the old approach has left a trail or wreckage in its wake.

30

More excellent material. When do you sleep???