How Central Bank Policies Created the Global Housing and Affordability Crisis

It's not just Canada. It's not housing supply and demand. It's not immigration. It's not regulations and red tape. It's all around the world and central banks are 100% to blame.

Since the very first post in this substack, I’ve been writing about the link between central banks, interest rates, and debt.

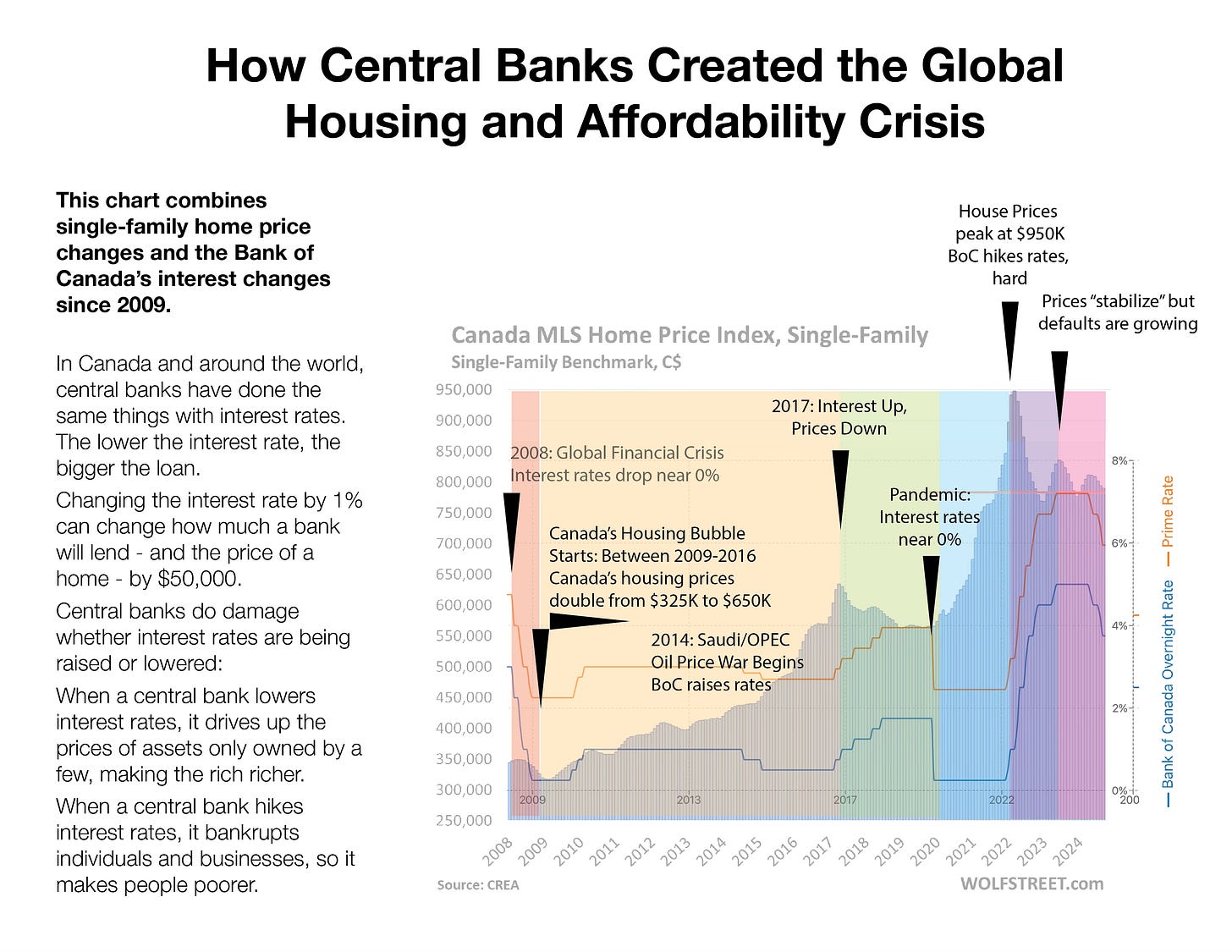

I wanted to see just how clear the connection would be if I compared the changes in price of homes in Canada with changes in the interest rate as set by the Bank of Canada.

I found the graph of the home prices in Canada here, at a really great website called Wolfstreet.

2008 was the Global Financial Crisis. Contrary to popular opinon, Canada’s banks were bailed out with over $100-billion in funds from the Bank of Canada, CMHC and the U.S. Federal Reserve.

At that point, the Bank of Canada dropped interest rates ultra low, which marked the beginning of the 15-year bull market in housing in Canada

The interest rates are from this site, where they are pulled from the Bank of Canada’s data.

What it shows, very clearly, is that dropping interest rates ultra-low drives up real estate prices, and increasing interest rates lowers them.

This is not a surprise. There’s an inverse relationship between interest rates and the amount of credit being offered.

When interest rates drop, more people become eligible for credit, and the people who already qualified qualify for more. Lowering interest rates means credit and debt penetrates more deeply into the entire population of borrowers.

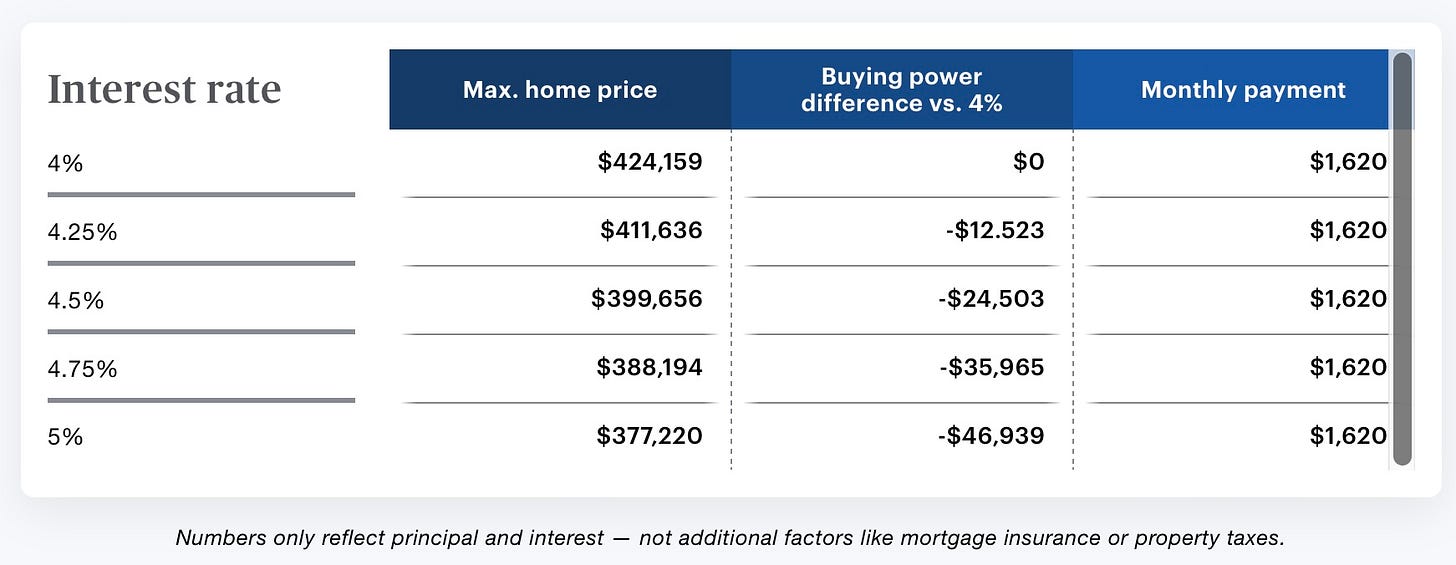

the size of your loan is calculated based on your monthly payments. The same monthly payment at low interest rates can finance a much larger loan than that payment at higher interest rates. Low interest rates create higher loans and more debt, and it is extended to more people.

So, as interest rates drop, the amount of credit banks are willing to extend gets larger, and it especially drives up the price of housing and real estate.

If a borrower can make a $2,000 monthly payment, a 30-year mortgage at 8 percent will finance about a $275,000 home. With mortgage rates of 4 percent, the same payment buys a $550,000 home. Lower interest rates also mean that people who didn’t qualify for loans before, will.

In the first article in this substack, I quoted Edward Chancellor:

Says Chancellor

The issue of lagging productivity and housing shortages is not unique to Canada. The U.S., UK and other countries like New Zealand and Australia are all facing housing shortages, as well as productivity challenges.

From the US in 2022: There's a massive housing shortage across the U.S. Here's how bad it is where you live

From Australia, 2021: Experts say this is what Australia needs to do to solve the housing crisis

From New Zealand, 2022 (which experienced a housing crash in 2023): New Zealand’s housing crisis is worsening

From the UK, 2024: 'We need more homes to ease the housing crisis'

It’s not just Canada. It’s everywhere. And there’s a reason it’s everywhere, even for countries on the other side of the planet from one another.

It doesn’t matter what type of government is in charge, or what type was in charge ten years ago.

Virtually every single country has people at each other’s throats, because while so many people are treading water or drowning, a select few keep getting rich on stuff that keeps making life worse.

In fact, that defines the current age. Balzac once wrote “Behind every great fortune is a great crime.”

It’s not wealth based on creating new or enduring value. It’s wealth based on getting people to go into debt and to hand that debt to someone richer who has placed a private toll booth on an economic transaction.

The reason these crises are happening around the world, at the same time, is that to deal with the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the 2020 Global Pandemic, central banks and governments around the world coordinated to lower interest rates and provide quantitative easing, because the world’s financial institutions and lenders faced a complete lock-up of their lending markets.

The 2008 Financial Crisis: Bad Mortgages Took Down the Global Economy

In 2008, the private financial sector ceased to function. It was a total collapse in confidence due to waves of defaults in U.S. mortgages due to yet another overpriced mortgage and housing crash, which was fuelled by ultra-low interest rates after the dot.com crash and 9/11.

That was in September 2008, and the U.S. Government and the Federal Reserve had to pump money into the system to keep it functioning, at all.

The explanation of Treasury Secretary Secretary Hank Paulson and U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke at the time was that the U.S. federal reserve had to take all the “troubled assets” off the books of banks and investors to keep them from going broke, and giving them newly printed cash to replace their reserves.

The assets were being “written down” in value because they were dangerously overpriced due to reckless lending that had been encouraged by the U.S. Federal Reserve’s ultra-low interest rates, which led to ultra-high mortgages and ultra-high house prices.

Paulson told the U.S. Congress:

This is really important to realize.

“Illiquid” means that these assets aren’t producing money, and can’t be turned into money, because no one wants to buy them because they aren’t worth anything.

“Mortgage assets” are when investors would buy and bundle up of people’s mortgages into a single fund. The idea is that all the people paying their mortgages provides a reliable income stream, month after month, year after year.

So, you’re not paying your mortgage to a bank. You are paying it to an investor.

When these mortgages were bundled together into securities, the idea was that if a few people defaulted, the money from everyone else would still keep flowing.

This is where one of the basic ideas of the whole scheme backfired, because it didn’t consider how bad risk could be contagious. The idea might be that if you take higher-risk mortgages that are more likely to fail, and add lower-risk mortgages, that you have reduced the risk of failure.

This is like having two rooms next to one another with a door in between, where one room is on fire, and opening the door thinking it will help cool off and put the fire in the first room out.

Despite their shaky foundation, these securities were often graded AAA by ratings agencies, which is the top rating and the same as U.S. Treasuries, which are government bonds guaranteed by the U.S. government. It is impossible for the U.S. government to default on its debt. It is completely inaccurate to say that a mortgage-backed security is as certain to be paid back as a U.S. government bond, where the guarantee is 100%.

So investors, including banks and financial institutions, would have these securities as part of their reserves.

As it turned out, lots of people couldn’t afford to pay their mortgages. Contrary to the belief that borrowers were “reckless” or living beyond their means, there was widespread swindles and even forgery locking people who qualified for better mortgages into worse ones, to extract more profit.

When the mortgages couldn’t be paid, the investments, which were the basis of reserves for banks across the U.S. also collapsed.

The foundation on which the financial system had collapsed. While banks don’t lend from reserves, they use reserves to pay each other, and they need to maintain reserves to keep extending credit.

It put all businesses at risk, whether they had any of these investments or not.

The whole economy and businesses depend on short-term loans for businesses, who rely on it to keep the entire system going. It is generally considered a safe and low-risk market.

For example, a chain of stores may need to cover payroll, so they will borrow a large amount of money for a day. They might borrow $1-million one day on the market, knowing they are receiving payment for something else and can pay it back the next day.

As Paulson told Congress

“Every American business depends on money flowing through our system every day, not only to expand their business and create jobs, but to maintain normal business operations and to sustain jobs.”

The straw that broke the camel’s back in the U.S. economy was when the “paper” market which is considered one of the safest and least risky markets, returned a loss instead of a gain. It’s called “breaking the buck”

“On September 17 [2008], investors fled money market mutual funds. The Reserve Primary Fund broke the buck and caused a money market run.”

If no one was willing to put money into that market, businesses across the U.S. would immediately grind to a halt and there would be a cascade of failure because the money that companies use to pay employees and suppliers would not be there.

A massive program ensued which meant that “troubled assets” and “toxic assets” were purchased by the Federal Reserve, which provided cash to restore “liquidity” in the form of quantitative easing.

Now, it has been argued that another solution would have been to forgive the mortgage holders and their mortgage debt, and it would have been more efficient and effective.

It is not an exaggeration to say that what happened instead is that the federal reserve let homeowners go bankrupt, and provided companies with the cash to buy up the homes at distressed prices.

This was an inflection point in history, because the most recent housing bubble has been growing since this point - 2009.

Ultra low-interest rates followed, which meant re-inflating the price of houses again in order to drive the economy.

QE and ultra-low interest rates became the standard method to deal with these crises. The same economic assumptions and practices were kept in place.

The Pandemic

Because nothing has actually been fixed in finance since 2009, the risk of another crash was growing. William White, an economist who predicted the 2008 crash, warned that debt levels - private and public - are unsustainably high.

In 2019, “Overnight lending rates topped at an annualized rate of 10% last week, four times higher than the prior week. That essentially meant some banks were willing to pay upwards of 10% interest rates for cash.”

The U.S. Federal Reserve responded by setting up a “Standing Repo Facility” to keep those interest rates down - by making sure money was always available to borrowers. Because of the jargon people don’t grasp it, but what it means is that the U.S. federal reserve was using public money to make sure that people could borrow at lower interest rates.

This was a sign of trouble, which increased over months, that what is called the “interest cycle” was coming to an end - which is to say, that people were once again reaching the end of their rope in their capacity to pay their debts.

In Canada, the price of a single family home had tripled due to the interest rate stimulus. While it was driving economic activity and tax revenues, it was not building lasting value - houses, after all don’t generate ongoing revenue for the owner, but mortgages require the owner to generate ongoing revenue for the lender.

During the pandemic, the same thing happened to lending and the economy, for different reasons, and it was not as openly disclosed.

The declaration of a global pandemic and health emergency on March 12 meant there was no certainty at all. The price of oil went negative. There was no way of knowing the future impact of the pandemic, the costs, the duration and how businesses would get revenue and pay their bills.

The credit markets once again locked up. The response from the U.S. federal reserve and central banks was essentially the same as 2009. They immediagely committed to billions of dollars in quantitative easing, providing cash in exchange for assets that were plunging in value. They bought assets and securities from banks. To ensure that governments could keep borrowing, they bought government bonds from investors.

The combinated of QE and ultra-low interest rates resulted in a massive increase in loans - a tsunami of credit which helped drive the housing and affordability crisis, because it has driven an unintended - but entirely foreseeable - speculative bubble in property and stocks.

It has all made inequality worse, by making the rich much richer. Driving up the price of all those assets means that the new owners face huge pressure to recoup their costs by raising prices and rents. The more you pay for an asset, the harder it is to recoup your investment.

It has made affordable housing unaffordable.

The trap

The housing and affordability crisis in Canada and around the world is not because there are too many people, or because there is not enough space, or because there are too many rules. It is not because of immigrants.

It is because the Bank of Canada, like other central banks, has made it their policy to blow housing bubbles as a way of boosting the economy.

While this makes a few people very rich, very quickly it creates a lasting crisis, because housing is not a productive investment and because it is a necessity of life.

The debt-driven distortions in the market mean that prices are so high that affordable housing cannot be built.

It is not just a problem of supply and demand for houses, because it is no longer a housing market. It is a housing and mortgage market, and lowering the price of houses is opposed by several forces.

There are recent homeowners with a high mortgage who, if housing prices drop, can be “underwater” on their mortgage. They owe more than the home is worth, which means that if they sell, they will have less than nothing: they will be left paying interest on something they no longer own.

There are existing homeowners whose major asset is their home, and they are relying on it as a “nest egg.”

The third is the mortgage owner - a bank or an investor. They do not want their investment to drop in value.

That mortgage debt acts as upward pressure on prices. They have to come down, but they are being suspended by the excess debt that drove up the prices in the first place.

The reason there is no good solution (yet) is that people wait for a “correction” which is a recession and a housing market crash, while pretending that it is just “the market” at work when the entire damaging and tragic fiasco is driven by central bank policies.

What free market?

If anyone asks the justifications for why a central bank would create hundreds of billions of dollars or trillions of dollars in public money and give them to financial institutions, and not, distribute it to individuals or to government, the reasoning is supposed to be that it is well established that the market is the best way to allocate scarce resources.

It has to be said, this is a tough argument to swallow, since these massive outlays of public money are happening because the investments that financial institutions made have failed.

These policies have been incredibly damaging and have made life harder for the vast majority of people and have profoundly warped our economies.

Central banks are supposed to be independent so that they - disciplined and wise money creators - are not captured to and subject to the whims of supposedly irresponsible politicians who are money spenders.

Politicians are still held to account for their mistakes through public criticism, opposition parties, debates, and elections.

One of the defining problems of central banks is their lack of accountability. As a human institution, they are fallible and make mistakes - but everyone else has to pay the price if they get it wrong.

Central bank policies have helped create more billionaires while bankrupting homeowners, businesses, and while making housing unaffordable.

They have increased the debt overhead on the entire economy, which means that people are spending more and more of their incomes servicing debt, instead of saving or investing.

When they create asset bubbles that crash, governments and taxpayers are on the hook, whether it’s tax increases, deficits, or cuts.

The reason it is so important to recognize the damaging role of bad central bank policy is not a question of blame or shame.

Elected governments acting alone do not have the capacity to fix what central banks have broken.

Central banks have powers to create problems that only they have the power to remedy. The idea that central banks only have the power to make things worse, and not better, is not tolerable. They are not infallible, and their decisions have the capacity to ruin lives and economies.

Central banks and governments need to look at how they can safely undo the damage they’ve done.

For 50 years, trying to fix the economy with interest rates alone has been “Heads I lose, tails you win” for the vast majority of people living in the developed world.

Central banks manipulating interest rates have been an engine of inequality. Rates go down, it makes a few people much richer. Rates go up, it makes a lot of people much poorer.

That is a policy choice. Whatever future economic crises we may face, could be addressed if central banks just made up for their mistakes. There are plenty of them.

-30-

DFL

Ever considered getting back into politics, this time at the federal level? The NDP could really use you.

Yeah usury is perverse. But lowering the rate does not "drive up" asset prices, it moves asset prices once, it is a one-time adjustment. Natural rate of interest is ZERO.

I read the situation with the markets as more like the house prices are more about all sorts of other institutional forces as well as rates, like greed. Banks will make loans to only credit-worthy customers (if they don't want to get caught). But what are the prudential regulations? Who is enforcing them? Has there been a "relaxation" back to fraudulent appraisers and real estate commission grifters and all that scam side of things? That has to be a huge part of the price of a house. It's all disgusting form every side you smell it from.