The Modern Economy: Gambling on Whether the Middle and Working Classes Can Pay Their Mortgages

Debt and the housing market drive the business cycle and create modern financial crises. The house is not the investment: you are.

People are often told that their home is an “investment” – based on the idea that it is an asset which people assume will grow in value.

There are a couple of problems here. The first is that housing is a necessity of life.

Investments are generally something you put money into if you have some extra. Being housed – like having access to food or clean drinking water - can make the difference between life and death.

The other is that your own house is not a productive investment - they don’t generate ongoing revenue for the owner, like investing in a business would.

If you lend money to a baker to buy ovens for baking, to a delivery service for trucks, to a manufacturer for capital machinery, those are productive. Your own personal home or vehicle are not.

When you own one home, it is a necessary cost. It is not, in any meaning of the word, a “productive” investment, because it does not generate revenues that will help pay for itself while you are living in it. What’s more, the value of the property may rise or fall whether there are any improvements or not.

When you take out a mortgage to buy a house, it is an investment - but not for you, as a homeowner.

The real investment is not the home - you are. The bank is investing in you, and giving you a mortgage that you will have to pay back. Your mortgage is a “promissory note” – a legally binding promise that you will steadily pay back all the money you received, and then some.

The house is not the investment: you are. If you can’t pay your mortgage, and you default, the bank can seize your property.

The fact that you and your mortgage are the investment is very clear: because the mortgage may then be sold by the initial lender to other investors.

Since mortgages involve people making their payments on a regular basis, they are sold as investments that generate “passive income” – as if all the mortgages and the houses they are tied to are a kind of decentralized apartment building, where all the owners are paying rent to absentee landlords.

This inevitably leads to a crisis, for a number of simple reasons. First, individual homes are not businesses. They are not “productive” assets because they don’t generate revenue on an ongoing basis to pay for themselves. If the homeowner wants a return on what they paid for their home, the home has to go up in value, quite drastically.

The idea that prices are driven by supply and demand alone ignores the distortions created by debt and treating homeowners and mortgages as an investment.

The destabilizing impact of private debt should be clear from the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), which was caused by bad mortgages, packaged into bad investments, backed by bad insurance, all leading to bank failures and a global financial meltdown. Yet, few saw the crisis coming because orthodox, neoclassical macroeconomics have a blind spot: they don’t model debt, banks, or money.

The destabilizing impact of private debt should be clear from the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), which was caused by bad mortgages, packaged into bad investments, backed by bad insurance, all leading to bank failures and a global financial meltdown.

Financial crises throughout history have been caused by people betting on “new property” that promise vast returns– the South Seas Bubble, the Mississippi Scheme, even the Internet and Cryptocurrencies. When people borrow to buy, they lose all their money and their ability to repay. The result is not only poverty – but poverty accompanied with debt obligations.

The development of a modern housing market, with the vast amounts of private debt used to buy, built, and bet on it have changed many economies.

In 2016, Paul Romer wrote that macroeconomics is so disconnected from reality that it was “post-real”. It’s worth understanding mainstream assumptions first before we focus on why private debt is destabilizing.

People may think of low interest rates as making debt “cheap, but so-called “easy money” drives up prices. Low interest means bigger loans, and debt that penetrates further and more deeply into the economy, because people who did not qualify for loans before can get them, and people who already qualified can borrow even more.

If a borrower can make a $2,000 monthly payment, a 30-year mortgage at 8 percent will finance about a $275,000 home. With mortgage rates of 4 percent, the same payment buys a $550,000 home. The fact that the mortgage is secured against the “asset” doesn’t change that you are borrowing twice the money on the same income.

Debt-driven price increases, especially of real estate, sets two economic feedback loops in motion.

First, rising housing prices sends a signal to banks to keep lending for mortgages, which drives up prices more. Then, as those prices rise, so does overhead for the whole economy: rents, debt, interest, insurance, all resulting in a lower return on investment, for workers and business alike. This sends a signal to banks that lending to “real economy” businesses is risky - even though it would result in higher productivity and wages.

As a consequence, the FIRE sector (finance, insurance real estate) grows and undermines the ability of the rest of the economy to service its debts. When the system reaches a crisis, and defaults spread, the “financial implosion” happens - money disappears, and some banks may collapse. Others reduce or stop lending. As businesses fail and liquidate, and people lose their jobs, prices, and wages both drop - deflation.

Fiscal conservatives and neoclassical economists argue against government stimulus, believing that if we just let prices and wages fall until people can afford to start buying and hiring again, the economy will recover on its own. This can’t happen. Debts are always, by definition, more money than was loaned in the first place.

Deflation makes debt harder to pay off, just as inflation makes debt easier to pay off. As a result, there is a persistent debt overhang, even for people and companies who still have income.

In the 1990s in Japan, it was called a “balance sheet recession.” In 1989, real estate in Japan was worth 50% of the entire world. After it crashed, Japan struggled for years.

Booms and Busts: When Japan was worth the World

It is important to understand the role of banks and private debt in driving booms as well as the serious crashes that follow. An example of what happened is Japan in the 1980s and since.

In the 1950s, after the second world war, Japan was known as a place where low-cost, low-quality goods were made. Over the years, their low-cost goods became higher quality household names. Sony started selling transistor radios, then became a technology giant. Toyota and Honda both made small, low-cost cars that eventually became known for reliability and eventually developed luxury brands. By the 1980s, Japan had become a global economic powerhouse and was selling huge amounts of goods to the U.S. and around the world.

At the same time, Japan’s real estate market went wild. At one point in 1989, Japanese real estate was worth 50% of all the property in the world.

Think about that for a moment. The Japanese real estate market was worth the entire rest of the world combined. 1.3 square miles near the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was worth all of California. Another suburb was worth all of Canada. The value of all this real estate was fuelled by debt and by Japanese banks. Japanese banks were among the largest in the world.

In early 1990, the Japanese stock market, the Nikkei, crashed and the housing market collapsed shortly thereafter. When prices started to drop, the banks started to go broke. Many corporations and people were weighed down with colossal debt.

Technically, many corporations were bankrupt, because they owed much more than they owned - except they still had cash flow. They were “zombie” companies - even though they workers were still being paid, making products and providing services, and taking in revenue from sales.

As economist Richard Koo explained, Japan tried just about all the things those other countries did after the 2008 crisis - and it didn’t work. This included:

Guaranteeing bank liabilities

Quantitative easing (printing money to buy bad assets from banks)

Running a deficit to stimulate the economy, and

zero percent interest rates.

After seven or eight years, they realized that corporations were not trying to maximize profits - they were trying to minimize debts. Even with zero percent interest, companies were not borrowing to invest - for a full ten years, between 1995 and 2005. In fact, they were paying down trillions of dollars in debt - equivalent to 6% of Japan’s entire economy.

As Koo says, of course it makes sense for each individual to pay down debt - especially if they are “underwater” and are technically broke, because they owe much more than what they own.

Even with rock-bottom interest rates, they are not going to borrow, because they are already in too much debt. When this happened in the Depression, in the US from 1929 to 1933, the economy shrank by half.

The private sector and businesses have no choice - they have to keep paying down debt or go broke. Central banks can’t lower interest rates when they are already at zero.

The only way to keep the economy moving forward and inject new money is to have the government borrow and spend. Japan did this. The economy would start to recover, then people would complain the deficit was too high, so it would be cut, and the economy would stall again. The government would put in another fiscal stimulus, the economy would improve, people would complain again that the deficit was too high, it would be cut, and the economy would slump. This happened for fifteen years.

Exactly the same thing happened in the US. Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected in 1933 on the promise of a New Deal, and won the House, the Senate, and the White House. By 1938, more Republicans were elected, and they demanded spending cuts. When the cuts happened, the economy collapsed again. Then spending in anticipation of the war started to lift the economy up again.

Keynesian stimulus alone is not enough, because instead of creating new value, new injections of money go to paying off old bills and interest. For stimulus to spur growth, the ever- growing vacuum “negative money” of old debts needs to be cleared or restructured. The principal has often been repaid – what is left over is mostly accrued interest.

There is an idea in economics that all the factors will automatically come back to “equilibrium” or some natural balance. This is a false and ideal premise of how things are really work.

It is like the idea that natural populations of predators and prey will follow a cycle. In a given year, if there are few foxes, there will be more rabbits. The more rabbits there are to eat, the more foxes - then the foxes will eat all the rabbits, and the cycle continues.

There are no such natural checks in an economy. It doesn’t just rebalance itself at the same level The foxes can hunt the rabbits to extinction.

Debt and compound interest grow on their own.

It is only deliberately balancing the debt with new spending, or by clearing away the dead weight of debt that new investment and growth can happen.

Many economists and politicians have taken just the opposite approach - those recessions and financial crises should be followed by balanced budgets, even in bad times, tax cuts, and cuts to services.

The Special Treatment of Debt as an Investment

This expectation of no losses for lenders is so profound that when debt and financial crises happen, instead of offering relief to the jobless and destitute – who are no longer able to pay their debts and may be bankrupt – governments and central banks rush to the aid of the lenders, in order to sure that they are kept afloat or made whole.

During and after the global financial crisis, governments and central banks around the world gave trillions of dollars in cash to banks and investors, so they would stay afloat and be able to keep lending. Much of it was not but newly created money, and it was used to buy the supposedly “toxic assets” – mortgages, houses and businesses that had defaulted.

Banks have been protected, as risks and losses are shifted onto the rest of the economy: government, workers and industry who face austerity and insolvency.

Since 2008 governments and central banks have printed tens of trillions of dollars for private banks and investors through “quantitative easing.” In 2020, banks and bondholders got trillions in newly printed money in exchange for bad assets in order to keep lending. Central banks manipulated the markets to prop up asset prices, whose ownership is incredibly concentrated.

Since 2008, the global financial sector has been dependent on governments and central banks being willing print public money for their private benefit, the commitments from officials have, literally, sometimes been without limit.

The global economy has turned into a casino where governments cover high rollers’ bets, even when they lose. What to call this new economic system? It is certainly neither “free market capitalism,” or socialism. An anonymous Financial Times commentator called it “financial communism.”

Extraordinary crises require an extraordinary response, yet all we have is the same two “left-right” options: more public debt and higher taxes on the one hand, or austerity and more private debt on the other.

What is required is a strategy to reduce for debt restructuring, which is what William White has argued.

There’s a saying that “Debts that can’t be paid, won’t be.” The question for policymakers is to come up with a plan to make sure that if defaults are inevitable, that steps are taken to mitigate the harm, and keep risks from spreading. Orderly, structured defaults and debt renegotiation is preferable to chaotic defaults.

White writes here:

“These shortcomings point to the need for explicit debt restructuring or even outright forgiveness. However, the administrative and judicial mechanisms needed to do this effectively are lacking and need to be put in place. In recent years, the Working Party on Macro-Economic and Structural Policy Analysis at the OECD and the Group of Thirty have published extensive documentation of current shortcomings and suggestions for improvements. Procedures for resolving debt problems in the corporate and household sectors need improvement. Not least, “zombie” companies must be restructured rather than be given “evergreen loans” as is currently the case. Indeed, measures taken to reduce the economic costs of the pandemic have sharply worsened this problem. Procedures for resolving financial sector insolvencies are even more inadequate. The problem of banks that are “too big to fail” must be dealt with definitively. We also need an accepted set of principles for the restructuring of sovereign debt.

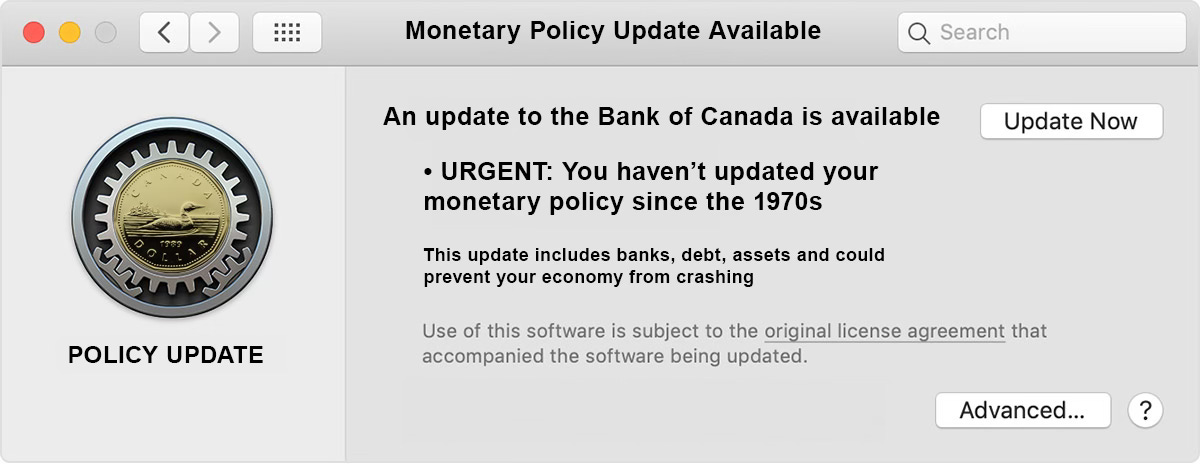

For example, let’s accept for a moment that people are being harmed by the Bank of Canada’s manipulation of interest rates. It is reasonable to expect that people be allowed to renegotiate their debt.

Restructuring debts after a crisis, and after wars, is also common, because the economy is massively distorted by the crisis.

We have just experienced the single worst global public health emergency in a century and there are wars breaking out. Pruning the debt burden will stabilize the economy, by reducing the continuous extraction of payments from the rest of the economy. Governments, the bank of Canada and the private sector can then work together so growth can begin again.

The Great Depression of the 1930s did not end with the New Deal and government programs. It was the Great Compression from 1938-45 - an ultra-high pressure economy, where unemployment went to 2%, the entire U.S. industrial tool stock doubled at public expense, and almost as a side-effect, reduced personal debts. Thus was created the North American middle class, setting the stage for the post-war boom.

The same happened in Germany, who in 1948 monetary reform that paired debt forgiveness with “helicopter money” which meant printing money and giving it to people as to get them going.

In Canada, after the Second World War, the Federal Government forgave the Depression-era debts of the prairie provinces.

Debt restructuring alone is not enough: but is an essential step in true renewal.

There are multiple practical ways of dealing with it, which ideally would be negotiated and democratically legislated. One political challenge is that Central Banks would have to act in the interest of the entire economy, and not just the financial, insurance and real estate sectors.

The Bank of Canada’s legislative mandate when created in 1935 was always larger than just suppressing inflation – which seeks to reduce prices by increasing the supply of distressed properties on the market by raising interest rates so that debt drives people and businesses into default.

The measures above – debt relief, industrial and employment programs, and a so-called “high-pressure” economy would not only spur healthier and more balanced economic growth, it would help people cope with whatever the economy throws at them - deflation, inflation or debt.

It can also be more environmentally efficient economic growth because so much of our current economy is we are not working to get a ahead, we are working and falling behind to pay off ever-growing debt.

That is debt is growing on its own – it is not an added cost because of more workers, investments in innovation or upgrades to technology or infrastructure. It is because interest doubles and doubles on itself. It is an added burden and cost - it doesn’t create value - it is extracting it.

You could prevent a Depression or a financial crisis ahead of time by creating tools to restructure personal and farm debts. It would remove the upward pressure on prices because the overhead of debt payments would be gone, and so would the spiralling housing costs that are driving people out of the job market and driving their demands for raises.

It is critical to more positive growth – and offers an opportunity to rebuild and make things right. For many people and businesses, the idea of shifting to “environmentally friendly” options – or even getting better insulation for their houses – is financially impossible, because they are carrying debts on the equipment they own.

FIRE: How mortgages came to drive the business cycle

One of the fundamental changes in the economy in the 20th century, was “personal finance” – the fact that people would take out mortgages to buy and own their own homes.

One of the reasons that the idea of banks creating private money in the form of debt - especially mortgages - is so important is because of the way it affects the overall economy.

Banks are competing with one another for customers to lend to, because the more mortgages they create, the more assets they hold, and more profits they make in interest payments.

So as banks increase lending and money creation for mortgages, it drives up the price of property and real estate. As prices rise, so do mortgages, and the two drive each other upwards. Real estate is often seen as an “investment.” For people with more than one place to live, this is certainly true - but a person who is living in a home when all property is rising in value can’t liquidate their one home. They have to find a new place to live, which may be as unaffordable as the one they just sold.

However, a home is a necessity of life, and real estate and property is also overhead, for people as well as businesses.

There is a critical distinction between the different parts of the economy that has been lost. Very often, around the world, politics is considered to be polarized, between “business” and “workers”. There are three groups that make up the private economy There are workers, there are productive businesses (industry, for example - the so-called “real economy”), and then there is the FIRE sector - Finance, Insurance, Real Estate.

The reason workers and industry are different than the FIRE sector, is that workers and industry create new value, while the FIRE sector makes money from money.

The distinction is important, because it’s not just a labour issue. It’s a business issue. When we talk about inequality, or wages, or incomes being stuck, close to the same as they were years ago, it’s not just workers who have been stuck or lost ground. So has industrial capitalism. The real economy. From agriculture to manufacturing, to creative work. Whether we are talking about being a skilled labourer or having a craft, instead of having finance service that economy, we are are all working to service finance. That is part of the problem with our economy right now, and why it is out of balance. Finance helps drive up the cost of real estate, which allows insurers to make more money as well.

As the FIRE sector grows - and especially as real estate goes up in price, it becomes harder for other types of businesses as well as workers to pay their bills. The reason we offshore our manufacturing is because our businesses and labour can’t compete with developing countries because their workers and businesses face don’t have such high overhead in rent and debt.

The housing and real estate sector has grown to become an enormous part of the economies of developed nations. It is not based on added value - it is based on people buying, often using debt, with the hope that they will money from a rising market. There is a word for this - “speculation”.

We usually think of “speculation” in terms of people gambling on the stock market. What colossal mortgages and real estate bubbles do is turn millions of people into gamblers who may be borrowing hundreds of thousands of dollars on a bet that can go wrong. When it does, it’s called a recession - or sometimes even a depression or a financial crisis.

Downturns are often called “corrections” - which somehow suggests that something bad was happening and it is now being fixed. Many economists and politicians look at what happens in a downturn and think that it is necessary, and that government should not interfere. Prices of goods and workers’ salaries alike may drop as unemployment goes up. This is treated as a necessary part of the business cycle, and that wages should drop until the point that people start hiring again, at which point the system will return to some kind of balance.

There is a word for dropping wages and prices - deflation. Normally we think of low prices as a good thing. However, what economists (and many others) missed is what happens to all that debt. There is a general horror today of inflation - of rising wages and prices. One of the things that inflation does is help people - and businesses and governments - pay off debt more quickly.

Deflation - dropping prices and incomes after a downturn does just the opposite. It makes debts harder to pay off, at a time when people and companies alike may be stuck with a debt overhang. In the great Depression of the 1930s, the President’s advisors were “liquidationists” - they thought that everything should be sold off for cash. However, as businesses fail and sell off their inventory at a discount, it undermines even businesses without exposure to debt.

Today, recessions and downturns are viewed like hangovers after a party. The idea is that people were living too large (and often, the government was spending too much) and that people were careless or reckless with their money. People were overdoing it, and after that, it means that people need to “tighten their belts” or clean up their act. There is a moral and psychological aspect to it as well - because so many people are hurting because they are out of work or have lost their homes, businesses or savings, there is a sense that someone must be punished. This is where the policy of austerity has come in. It provides a sense of satisfaction - even though it may not work.

This debt trap is what turns recessions into depressions. As the economist Richard Koo said, a recession is like a cold, and an economic depression is like pneumonia - it needs completely different treatment.

There are always measures available. Governments and Central Banks should be talking about new ways of doing it, now.

Remember:

When you take out a mortgage to buy a house, it *is* an investment - but not for you, as a homeowner.

The real investment is not the home - you are. You are the one who has to pay the bills. That's problem one.

Your house doesn't generate revenue. That's problem two.

What's driving prices is speculation - another word for gambling - that the price of houses can keep going up, based just on bigger and bigger loans, while incomes aren't catching up. That's problem three.

That is what is driving Canada's housing crisis.

You can read about what can be done here »

The Single Most Important Thing We Can do to Address Canada’s Economic Challenges

While some economic indicators in Canada are ripping higher, the struggles Canadians are facing are undeniable, and the current policies of the Bank of Canada massively adding stress to Canadian businesses and families alike, in the name of fighting inflation.