The Only Time Inequality Ever Got Better

The Great Compression Set the Stage for a Global Post-World-War II Boom. How it happened bears remembering.

When we talk about “income inequality” or “wealth inequality” it’s kind of a vague term. Really, what we’re talking about is “concentrations of income” or “concentrations of property ownership.”

When we talk about inequality getting “worse,” we’re really talking about the fact that more and more income and ownership is in fewer hands.

From the Second World War until the mid 1970s, while the economy grew, workers tended to share in the benefits of growth. Since the late 1970s and early 1980s, many incomes have stagnated (and wages for some have dropped) while the wealthiest have broken away from the pack. Sometimes, when the economy as a whole grew, inequality grew as well - so people at the bottom and middle might get better off, but the people at the top would get richer faster than the rest.

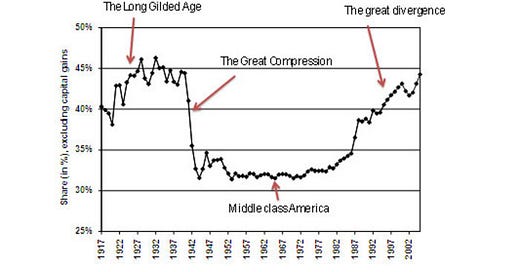

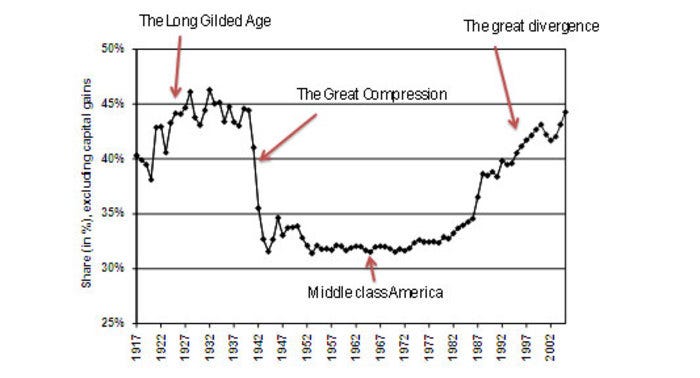

In fact, inequality has only ever improved once: during what is called “the Great Compression.” It did not begin with the capital losses of the Depression, but it does coincide with a second recession and “The Second New Deal” of the late 1930s.

Not only did wages rise for most Americans, the share of overall income of the top earners shrank. As Paul Krugman writes:

“The middle-class society I grew up in didn’t evolve gradually or automatically. It was created, in a remarkably short period of time, by FDR and the New Deal. As the chart shows, income inequality declined drastically from the late 1930s to the mid 1940s, with the rich losing ground while working Americans saw unprecedented gains. Economic historians call what happened the Great Compression, and it’s a seminal episode in American history.”

The concentration of monopoly power was the subject of an extraordinary speech by FDR in 1938. It dealt at length with many of the very issues we are dealing with today. To deal with unemployment, inequality, and exploitation, the government pursued all sorts of schemes. Ellen Ruppel Shell writes that:

“…prices were fixed to prevent large retailers from forcing smaller ones out of business. As part of the New Deal, the National Industrial Recovery Act set codes of conduct for business, including guidelines for hours worked, wages paid, and fair-trade practices. Low prices, it was feared, would force a dip in wages and profits, pushing more businesses into bankruptcy.” A number of other measures were introduced to prevent what we would call “exclusivity deals” and predatory pricing. A strike in Detroit had resulted in the formation of the United Auto Workers, and “as the car unions won successfully larger concessions for their membership in the mid-1930s, Detroit ranked first in the nation in private home ownership.

World War II blotted out this happy picture with the double whammy of scarcity and inflation. There was little on offer, and what was available was priced out of reach for most Americans. Car manufacture came to a halt in 1942 to make room for the war effort, and the price of textiles shot up nearly 30 percent, the cost of farm products more than 40 percent. While before the war the government had set legislation to keep prices from falling too low … in 1942, the Office of Price Administration and Civilian Supply … required merchants to set ceilings on the price of what eventually grew to be 90 percent of all goods.

There was rationing of rubber, sugar, gasoline, heating oil, milk, coffee, soap, nylon stockings and even used cars… Waste was reviled, and recycling was elevated to a patriotic duty. Interestingly, despite this enforced frugality, most Americans managed to live well, far better than they had in the Roaring Twenties when there was enormous income disparity. In 1944, the average factory worker’s pay had grown by 80 percent in five years, while, thanks in part to government-imposed price controls, living costs had climbed only 24 percent. And in 1945, personal savings reached an astonishing 21% of disposable income, compared to a mere 3 percent two decades later.”

https://www.mcnallyrobinson.com/9780143117636/ellen-ruppel-shell/cheap?blnBKM=1

In fact, those were the conditions that made the post-war recovery possible. During that time, the entire tool stock of the U.S. was doubled at public expense.1

Writing in 1976, Arthur Okun said “The relative distribution of family income has changed very little in the past generation. The nation took one big step toward equality during World War II; throughout the postwar period, the top income groups have received a substantially smaller share of income than they had in the prosperous years of the twenties.”

To recap: a period of scarcity, inflation, recycling, rationing, regulation and high government spending had the result of marking the only major decrease in inequality in U.S. history, with people making more money and saving much more. What’s more, trade was severely disrupted (to say the least) as supply lines to countries who supplied raw materials as well as manufactured goods were cut off, and there was no free movement of people across borders.

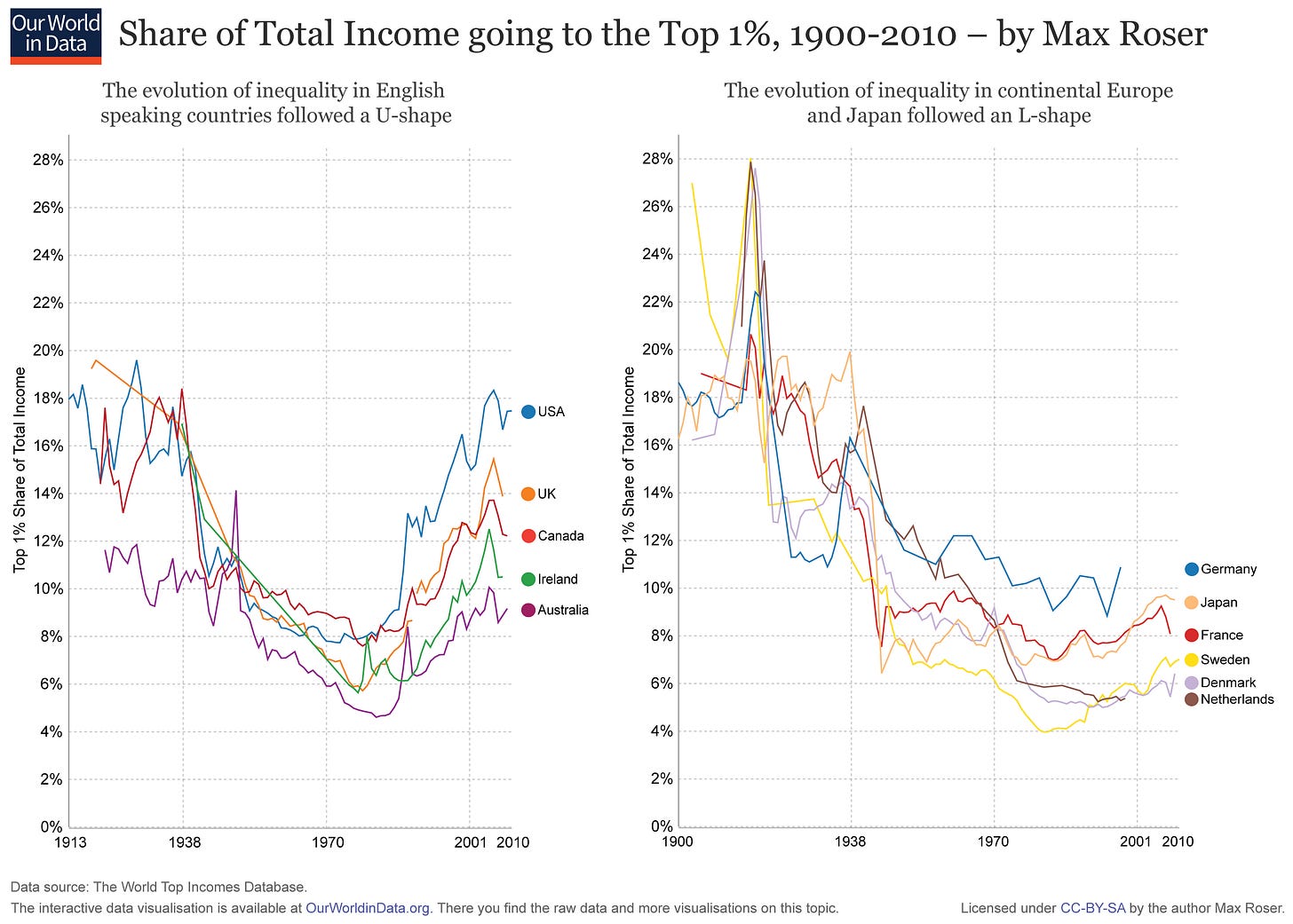

Another reason for the Great Compression was a progressive income tax. Switzerland never had a progressive income tax, and never experienced a compression. Writing in 2006, Atkinson and Piketty point out that:

“The United States, United Kingdom, and Canada display a substantial increase in the top-0.1-percent income share over the last 25 years. This increase is largest in the United States, but the timing is remarkably similar across the three countries. In contrast, France and Japan do not experience any noticeable increase in the top- 0.1-percent income share. As a result, income concentration is much lower in those countries than in the English-speaking countries.”

The Second World War also resulted in a whole series of innovations in science, physics, aviation, communications, computing and medical technology (as well as organization and governance). Many were the result of the existential threat posed by war (the atomic bomb, radar for detecting and firing on enemy aircraft and ships, computing to break codes) or from the necessity of developing alternatives when imports were unavailable. (Methadone was developed as an alternative to morphine when supplies of opium from the east were cut off).

The creation of the middle class in North America and elsewhere apparently occurred due to the opposite of all of the things that are supposed to create prosperity for all: high government spending and taxes (including deficit spending), high amounts of regulation, severe restrictions on trade.

The usual story is just to say “the Second World War ended the Depression for FDR” but this makes a mistake. First, organizing and prosecuting a war takes a fair bit of competence. The other is that the Great Compression clearly started before the direct involvement of the U.S. in the Second World War. Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, but the U.S. did not declare war until December 1941. The Great Compression started in 1938.

The question now is how to deal with inequality - if this is something governments are really going to be serious about. There is a focus now on what is called “equitable growth” - which means that we try to find ways to return to a kind of capitalism in which, when worker productivity went up, and the economy grew, so did income and wages.

The difficulty facing us is that even if we shift to equitable growth, it will not necessarily do anything to actually reduce inequality.

The market itself may reduce inequality if there is another serious market crash. The Great Depression was not just a stock market collapse in 1929, but a second downturn several years later, in 1938. While few people thinks 2008 can repeat itself, there is a huge amount of global uncertainty especially after the Pandemic.

The reason the issue of inequality matters is of course that it affects the economy: the main reason economies are sputtering is because there is no “demand” - when the vast majority of people’s wages and incomes are stagnant, they have turned to debt instead. But if wages and incomes don’t rise, people can neither spend on consumer goods nor pay back their debts.

There is an idea that even if we could fight inequality, that it would be a bad idea, because a growing economy is synonymous with growing consumption, and therefore worsening environmental degradation. But we are not working for growth - we are working to pay off debts.

This is another way in which the Great Compression shows us that is not the case: you can improve people’s financial well being without being wasteful: in fact, you can do it by making the most of every drop of fuel and scrap of metal, every person’s effort and time. There is, in fact, a stronger link between poverty and environmental degradation, because low wages make ruinous environmental exploitation possible - in fact, they encourage it and make it profitable.

It is also worth pointing out that many of the aspects of the Great Compression were temporary, and were lifted when the war ended:

“The National War Labor Board (NWLB) established in January 1942 and dissolved in December 1945, was responsible for approving all wage increases and decreases after the Stabilization Act (also known as the Price Control Act) of October 1942 made any wage change illegal without its approval.”

The regulation ended abruptly with the end of the war, but the positive effects lasted for decades. People think of the post-war era as being one defined by growing prosperity, but it is largely that people were reaping the benefits of Great Compression.

There are all sorts of reasons for arguing why the Great Compression could not happen again, and why we would want to avoid a crisis that would necessitate extreme measures. But it still shows that ever-growing inequality is not inevitable, and that we can choose a different path.

With a mix of wartime spending, wage and price controls, strategic use of resources and rationing, unemployment went down to 2%; and while inflation went up, wages went up faster (Shell 2010, 24-25). The tool stock of the entire country doubled - all of it paid for by government (Gordon 2016). By 1945, the average American worker saved 21% of their income (Shell 2010). Thus, the middle class was created. Whether it was deliberate or not, the reduction in debts resulted in greater prosperity.

Furthermore, 50% of the U.S. war effort was paid for through new taxes, 35% through bonds that were repaid and 15% through Federal Reserve Bond purchases (Institute for New Economic Thinking 2016). This era, from 1945 to 1975, was the so-called ‘golden age of capitalism’, with impressive growth among developed and developing countries alike: inequality did not get appreciably better, but the high growth of that period was more equally shared, so a rising tide lifted all boats.

Gordon, Phillips. 2016. "After 150 years, the American productivity miracle is over." Quartz. March 9. Accessed November 4, 2016. http://qz.com/633080/the-rise-and-fall-of-american-productivity-growth.

The expansion that occurred 45-75 cannot happen again without deeming the planet unlivable. Equity must be found through taxing, price and wage control. That will require replacing all the corrupt politicians and corrupt judiciary. At least three members of the Supreme Court are removable for corruption that exceeds even the lax laws they have created. History shows more extreme measures can be taken. Consensus is certainly for the more moderate alternatives. Elect working class politicians and hold them to task.

An error here stating WWll was declared in December 1942, it was in fact declared in December 1941