The "Theoretician of Totalitarianism" in our Standard Economics Textbooks

Vilfredo Pareto came up with the 80/20 rule and "Pareto Efficiency" or "Pareto Optimality". He was also a fascist appointed to the Italian Senate by Mussolini.

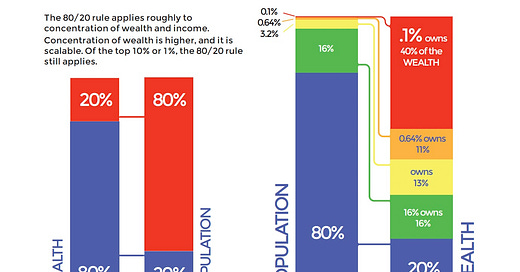

Above: how the 80/20 rule describes distribution or concentration of wealth.

Vilfredo Pareto was an Italian engineer, politician, agitator, economist and sociologist. Born in Paris in 1848 to a family of Italian aristocrats in exile — (neither he nor his father ever accepted their title) he was trained as a civil engineer. His training in engineering provided him with the mathematical ideas that made him one of the first people to provide a mathematical underpinning to economics and sociology.

Pareto has given his name to terms like “Pareto efficiency” or “Pareto optimality” which is a standard part of economic textbooks. There is also the “Pareto Principle” – the so-called 80/20 rule.

Before Pareto, thinkers like Adam Smith, or Mill were “political economists” making arguments based on principles or moral philosophy, not mathematics or statistics.

Pareto changed that. One of his contributions to economics — the “Pareto equilibrium” comes directly from his work in engineering.

Pareto only took up the study of economics when he was 42. An unexpected windfall from a wealthy relative allowed him to pursue studies full time, and later, when economics didn’t prove up to addressing the big questions, he started work in sociology, especially the issue of the concentration of wealth.

We tend to assume that in developed countries, wealth is held generally by a broad middle class. We all know that there is some inequality: we just don’t realize how unequal distribution really is.

Pareto looked all over the world and discovered what he thought was a universal rule: that in a given population, 80% of the land would be owned by 20% of the population. The inverse it also true: the remaining 20% of the property and income is spread amongst the other 80% of the population. It is in many ways a shocking statistic, and an astonishing principle. It is said to hold true not only in individual countries around the world, but is true of the global population as a whole, and even of the ten wealthiest people in the world.

That is because, as Pareto discovered, the distribution of wealth follows a “power law” — (not in the sense of political power, but in the mathematical sense of “number x to the power of y”).

Benoit Mandelbrot writes:

“What Pareto found, when he plotted income against the number of people … A power law was clearly present. In fact, his line sloped down instead of up, because the power was negative rather than positive. And alpha, Pareto’s name for the absolute slope of that line, was 3/2, he thought. What does that mean? Well, the gentler the slope, the more even the distribution of income…

Pick a group of people to study — say, everybody making minimum more than the U.S. government’s $5.15 minimum wage, or $10,712 a year.

Now ask: What percentage of people earn at least ten times that? According to Pareto’s formula, the answer should be 3.2 percent. Now go higher up the moneyed classes. What proportion earns more than $10.7 million? Answer: 0.1 percent And once more: What proportion earns more than $10.7 million, a thousand times the minimum? Answer: 0.003 percent — a very small number indeed.”

In 2006, a UN study showed that:

the world’s richest 1% owned 40% of all wealth, and that

50% of the world’s adults own just 1% of the wealth.

In the U.S., the imbalance is actually greater:

in the U.S. in 2007, the top 1% had 42.7% of the wealth;

the next 19% had 50.2% of the wealth, and

the remaining 7% of the wealth was split between the remaining 80% of the population.

A 2009 study of Canada showed 3.8% of Canadian households controlled $1.78 trillion dollars of financial wealth, or 67% of the total.

It’s a discovery — and a principle — that is both commonplace and scandalous. Commonplace, because it is has percolated down to everyday use in business and organizations of all types. It is assumed that eighty percent of your income will come from twenty percent of your customers, so if you want to become more efficient, you figure out which customers are your “best” and focus resources on keeping and grooming them.

Scandalous, because Pareto’s discovery was not a cool assessment: it was tainted by a number of political judgments that earned him the praise of the Italian fascists, who adopted him as their own, and the monicker “the Theoretician of totalitarianism” from Karl Popper. Benoit Mandelbrot writes:

“One of Pareto’s equations achieved special prominence, and controversy. He was fascinated by problems of power and wealth. How do people get it? How is it distributed around society? How do those who have it use it? The gulf between rich and poor has always been part of the human condition, but Pareto resolved to measure it. He gathered reams of data on wealth and income through different centuries, through different countries: the tax records of Basel, Switzerland, from 1454 and from Augsburg, Germany in 1471, 1498 and 1512; contemporary rental income from Paris; personal income from Britain, Prussia, Saxony, Ireland, Italy, Peru. What he found – or thought he found – was striking. When he plotted the data on graph paper, with income on one axis, and number of people with that income on the other, he saw the same picture nearly everywhere in every era. Society was not a "social pyramid” with the proportion of rich to poor sloping gently from one class to the next. Instead it was more of a “social arrow” – very fat on the bottom where the mass of men live, and very thin at the top where sit the wealthy elite. Nor was this effect by chance; the data did not remotely fit a bell curve, as one would expect if wealth were distributed randomly. “It is a social law”, he wrote: something “in the nature of man”.

That something, though expressed in a neat equation, is harsh and Darwinian, in Pareto’s view … There is no progress in human history. Democracy is a fraud … The smarter, abler, stronger and shrewder take the lion’s share. The weak starve, lest society become degenerate: One can, Pareto wrote “compare the social body to the human body, which will promptly perish is prevented from eliminating toxins.” Inflammatory stuff — and it burned Pareto’s reputation. At his death in 1923, Italian fascists were beatifying him, republicans demonizing him. British philosopher Karl Popper called him the “theoretician of totalitarianism.”

It is also remarkable that while Pareto’s concepts are a universally accepted part of modern economics, his fascist past has been bowdlerized.

It is hard to imagine Karl Marx’s ideas being taught without the mention of the calamitous failures, atrocities and famines of totalitarian communism in the Soviet Union or China, though Marx died in 1883, decades before his adherents sought to implement his ideas in the USSR or China. Pareto was appointed to the Italian Senate by Mussolini and the fascists, though he died before taking his seat.

In fact, as Mandelbrot notes, the ratio doesn’t hold everywhere in society — it tends to be true at the top, and it tends to reflect a concentration of wealth — or property ownership — more than income. But in both income and wealth there is huge inequality.

Even if they are aware of the 80/20 rule, most people don’t think about its significance. It is generally left-leaning economists and activists who talk about the issue of income inequality, only to be dismissed by because they “know nothing about business.”

Business, however is one of the places where 80/20 is taken as a given. It is taught as an organizing principle in any introductory business and marketing course. eighty percent of your revenue will come from twenty percent of your customers. eighty percent of income taxes are paid by twenty percent of the population; eighty percent of donations to charity are given by twenty percent of the donors.

Many philosophical, political, and economic theories do not take this distribution into account, or don’t consider what a difference it makes as a starting point when it comes to economic, fiscal, or trade policy.

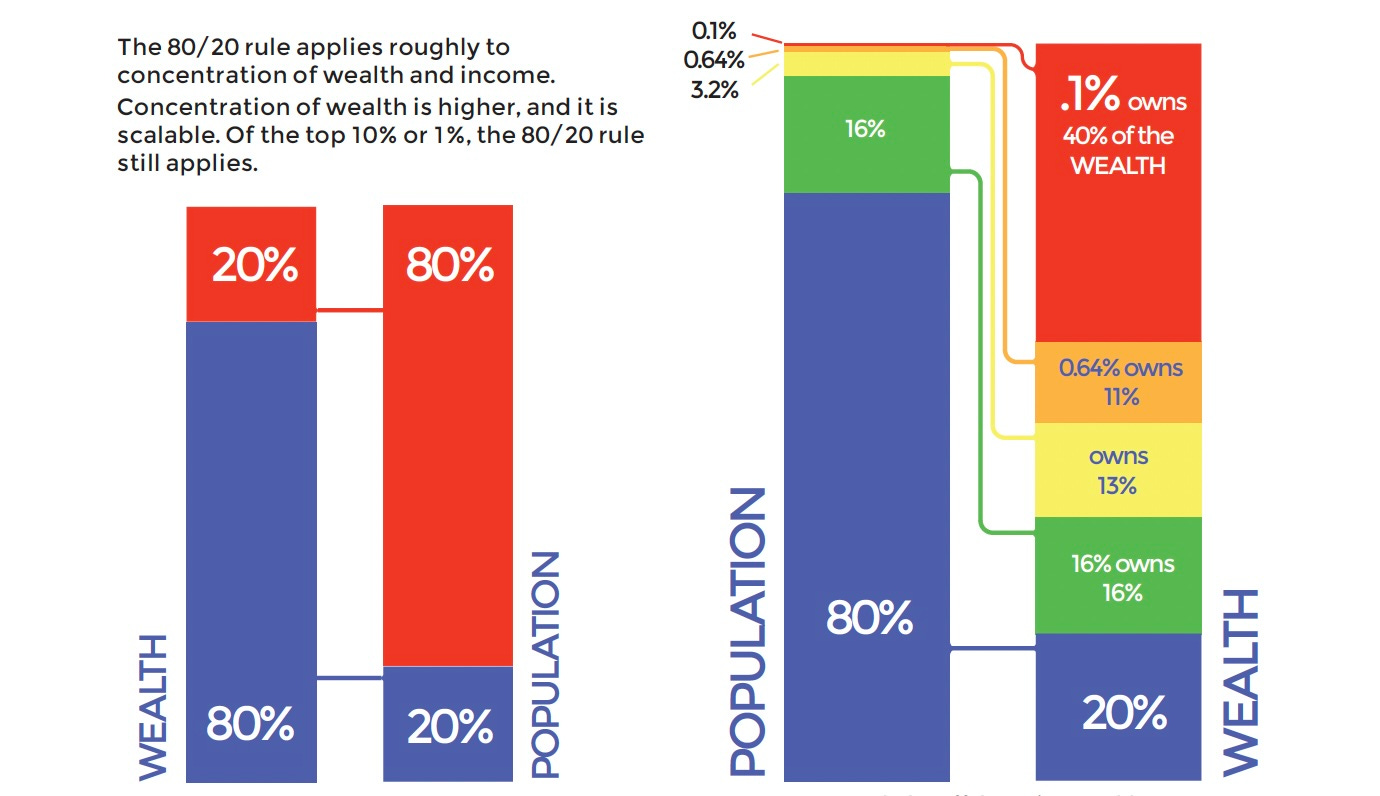

The way we usually measure inequality contributes to our misperception. Often, economists and statisticians will split the population into large segments — “cohorts” or five quintiles of eighty percent each, with each fifth being averaged out. This analysis is blind to the distribution it is supposed to reveal, especially when it comes to wealth. The 80/20 rule shows what a huge mistake this is: the top quintile — twenty percent — will have eighty percent of the total wealth (or income), and the bottom four quintiles will have twenty percent. Even within the top fifth of the population, eighty percent of the wealth will be held by the top twenty percent. And so on.

Quintiles use an average, spread out over a large population to measure concentration, which is a huge mistake.

There is an “economists’ joke” that explains it: A cat is cornered by nineteen hungry rats. The cat doesn’t really have to worry, says the economist, because on average, not only is each rat is five percent cat, but the cat itself is ninety-five percent rat.

Averaging out the incomes of the top twenty percent of income earners in a population will make it as if a great many people have high-to-middle incomes. In the U.S., the top quintile starts at about $100,000 a year, but only two percent of Americans will make over $250,000 a year. In Canada, the top quintile starts at about $75,000 a year.

At the other end of the scale, statisticians can talk about how much mobility there is, but there will appear to be great mobility in bottom quintiles — because people are making $21,000 a year (the second quintile) instead of $19,000 (the first quintile).

We are also blind to distribution because it isn’t considered as part of GDP, which measures overall economic growth, but not how it is concentrated. The focus on GDP alone has served to obscure the fact that the concentration of wealth has been growing steadily for decades. In Canada, “The typical household is now no better off, indeed about $3,000 worse off, than it was in the mid- to late-1970s, in spite of 35 years of economic growth.” In the U.S., wages have been stagnating for decades, even as stock markets have returned to record highs.

Wealth in Canada, 2012

Even Pareto’s concept of efficiency, which is considered shorthand for “economic efficiency” has a bias toward ever-growing inequality and against redistribution. It is not in any way a mathematical or economic measure of the use of efficient resources for an economy as a whole – energy, labour, time, or resources.

Rather – despite Lucas’ warnings against talking about distribution - “Pareto optimality” is a way of assessing distributional fairness which defines ever-growing inequality as efficient, and reducing inequality as inefficient.

Pareto efficiency appears to have a concern for fairness, because it asserts that no person in a system should be worse off, and as such appears to imply the need for a safety net or compensation for losses if they occur.However, initial conditions of inequality and imbalances in bargaining power that occur as it increases aren’t taken into consideration.

Under “Pareto Optimality” an economy where all the gains of economic growth accrue to one person while everyone else stagnated is considered “efficient”, as is an economy where all the gains accrue to one person, and everyone else loses – so long as they are compensated for their losses back up to the level of stagnation. However, an economy where everyone gained but the single wealthiest individual lost $1 would be considered “inefficient” – unless the wealthy individual were made whole again.

Pareto efficiency therefore defines growing inequality as “efficient” and addressing it as “inefficient” without any consideration on impacts on the functioning of the economy, growth, or demand. It is a shameful abuse of the term “efficiency” by the economics profession (the other being the “efficient markets hypothesis”) which is divorced from reality and cries out for reform.

In response to complaints of a collapsing middle class in developed countries, others will point to the fact that millions in developing nations have been lifted out of poverty. Here too, whether in China or India, the distribution has been incredibly unequal.

China’s explosive growth since 1980 has been hailed as a triumph for the free market and capitalism. Virtually all of the benefits have accrued to 20% of a population of 1.3 billion. With a population that large, improving the prosperity of hundreds of millions of people is no small feat, but as Ellen Ruppert Shell notes,

“While the nation as a whole has grown wealthier, China’s poor have grown poorer. World Bank economists reported in 2006 that the real income of the poorest 10% of China’s 1.3 billion people had fallen by 2.4 percent between 2001 and 2003, to less than $83 per year. And this was during a period when the economy grew by 10% and the country’s richest grew by more than 16 percent.”

Under Deng Xiaoping, China abandoned central planning and embraced what is considered a free market economy, despite rampant state ownership that no one would mistake either for a liberal democracy or private capitalism. Even calling it state ownership may be a mistake. Rather, it is an inherited oligarchy. As Bloomberg news reported in 2012, the Chinese economic miracle is :

“the result of a conscious decision by the former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and some of his closest associates — the so-called Eight Immortals — to safeguard the primacy of the Communist Party by putting their families in charge of opening up China’s economy… Three children alone — including Deng’s son-in-law He Ping and Chen Yuan, the son of Mao Zedong’s economic czar Chen Yun — led or still run state-owned companies that had combined assets of about $1.6 trillion in 2011, or the equivalent of more than a fifth of China’s annual economic output.”

From 1940 to the mid-1970s in Canada, the US and the UK, incomes of all groups rose together. Inequality did not improve, but it held steady, and the economic gains were better shared throughout society. In the mid- to late-1970s, that changed, and the top earners started to break away from the rest, with surges in inequality in 1987 and spiking upwards in the late 1990s and 2000s.

This is the result of a policy choice. It is possible to choose different policies (as other countries have) that still generate prosperity, including shared prosperity, with private business.

After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis - which should really have shown that the economic formulas and models we have been using are a failure, as Paul Romer noted in his 2016 paper, The Trouble with Macroeconomics, and as William White has also repeated, we need a new economics.

After 2008, the UK faced a longer and deeper recession than they experienced during the Great Depression of the 1930s. There was much more soul-searching and introspection, not least because Queen Elizabeth II was one of the few people with the sense to demand why no one saw the crisis coming.

The result was a significant amount of research into economics, its challenges, and its false assumptions - because it is treated as physics, and not as politics.

That work is being done at places like the Institute for New Economic Thinking

(https://www.ineteconomics.org) - while in Canada and North America, Junk economics pushed by think tanks remains the norm.

Why did the divergence in income start in the 1970s, and get worse and worse? In response to inflation from the oil crisis of the 1970s, governments — especially the UK, US and Canada — switched to a new economic model, Milton Friedman’s monetarism. It emphasized the power of the free market, labour mobility, deregulation, limited government intervention, and lower taxes, while private enterprise was switching to “maximizing shareholder value” and governments and central banks focused on fighting inflation.

Deregulated financial markets have resulted in far greater market volatility. Between 1940 and 1980 there were virtually no market crashes. Since then there have been dozens, which have wiped out millions of small investors while enriching small numbers of very wealthy investors.

Democratically elected governments have abdicated the role of managing the economy to unelected central bankers (sometimes at the urging of central bankers). In downturns, governments have been discouraged from running deficits to stimulate the economy through direct spending on infrastructure projects, or government hiring. Instead, central banks stimulate or cool off the economy by lowering or raising interest rates. The result is that individuals and businesses are expected to drive economic recoveries through debt instead of work. This has benefited owners over workers while driving up the price of assets: real estate and stock markets go up with wages stagnate and job growth stalls.

International trade agreements have reduced prices on some goods, but they have also created downward pressure on wages and driven up unemployment, while creating an outsourcing shell game. Entire factories are uprooted and moved to where the cheap labour is, with no new jobs being created. The same management and shareholders gets higher profits, the same machines, same products, new labour in another country, and joblessness or low-wage service jobs for the old labour.

Trade agreements place limits on the power of democratically elected governments to exercise sovereignty, or act in their own strategic economic interest - preferentially hiring their own citizens or local companies, and allow corporations to sue for lost future profits if governments bring in new regulations.

There has also been ever-growing concentration of economic power in the hands of a few as megacompanies engage in more and more mergers and takeovers, leaving communities with franchise- and branch-plant economies with low-paying local jobs, no local products, and all the profits being siphoned off to a foreign head office and shareholders.

The pursuit of “shareholder value” — which GE CEO Jack Welch later called “the dumbest idea in the world” — means squeezing all the stakeholders in a corporation in order to focus solely on the stock price, instead of long-term sustainability, innovation, or even profits.

Shareholder value has also led to increased outsourcing in order to boost profits or stock prices: a decent profit isn’t enough, only obscene wealth will do.

Deregulation of markets has resulted in massive, often unproductive financial sectors, some of which only trade in value, but don’t create it. Venture capital fuels innovation and builds and sustains new companies, but shorting the stock of a company you don’t own is gambling, not insurance.

When it comes to taxation, income from work — from “labor” — is taxed at a higher rate than income from owning — capital gains and dividends, and corporate tax cuts and loopholes mean that individuals are bearing a far greater share of the burden of the cost of government than they have in the past, while corporations are distributing the benefits of tax cuts to CEOs, executives and shareholders rather than employees.

All of these policies have a common thread: they devalue income from work, while rewarding income from ownership.

All of these policies have a common thread: they devalue income from work, while rewarding income from ownership.

The result is stagnation — or lower wages and longer hours for the many — higher profits and lower taxes for the few. No wonder inequality is growing.

The concentration of wealth” — of owning property or shares in companies — has always been greater than the concentration of income. But by pursuing a “race to the bottom” that pits workers in developed countries against workers in developing nations — the result is that over time, the inequality in our economies just reflects who owns what.

As inequality worsens, wages drop and unemployment goes up, the relative power of employers increases, so workers compete with one another out of desperation, and employers can have their pick of overqualified workers, each willing to work for less than the next person.

The result is not economic growth or a vibrant economy: it is an economy that is “dieselling,” like an engine that sputters and coughs but doesn’t turn over.

For 30 years, governments in Canada, the US and the UK have not sought to create more and better paying jobs. They have sought to find ways to get more cheap stuff, often by having production outsourced.

The fact that technology means we now have unnecessary gadgets that replace dozens of other unnecessary gadgets from 30 years ago does not address the basic issue: more cheap stuff from somewhere else does not help people put food on the table, put a roof over their head, pay for their children’s education, or their own health care or retirement.

This is particularly important in countries where politicians are suggesting that it is necessary to dismantle or cut back on social programs like health care, or further lower worker’s wages in order to be “competitive.”

We are where we are because of deliberate policy choices, economic policies that can be called “libertarian” or “neoliberal” or “neoconservative” that were supposed to create greater prosperity for everyone. They haven’t. One reason for this is simple: the hidden premise of these policies is that everyone is equal, when they are not.

It is possible to improve prosperity for the vast majority of people whose incomes have stagnated in West for a generation. It requires re-evaluating many ideas that have been conventional economic wisdom for a generation, which is no small feat. It also requires a renewed faith in the capacity of government to effect change.

35 years of rolling back government services and downloading costs onto citizens in the UK, Canada and the U.S. means that many think government has no role to play. Scandals, and betrayals of trust on the part of those in power — the surveillance state, and a kind of “two-tier justice” when it comes to wrongdoing by those in power means that people don’t believe that government is held in contempt and perceived as complicit with vested interests. In the 20th century, the far left (communists) and far right (fascists) wanted to accomplish their utopian/dystopian goals through totalitarian states. They were both opposed to liberal democracy.

Today, the left and right are anti-state: left-wing anarchists on the one hand and Ayn Randian libertarians on the other — both, again, opposed to liberal democracy and the institutions which can enforce the rule of law.

Withdrawing from civic life as a strategy is doomed to failure: it amounts to surrender, because it cedes the field to the most powerful. We have the tools at our disposal - democratic governments, the courts - to address these problem, and governments and political parties can focus on the common good — the economic interests of all citizens, and not just a powerful few. It may require a revolution in the way we think, but it does not require blood in the streets.

To understand why this matters — for the economy and for democracy — we need to understand just how unequal our societies are. Only then can we understand why our current economic models are failing, and why it is so important for the future of our countries and our and what we can do to fix it.

Many people react to the news of the “Great Compression” with a shrug, and say “or course, the spending required by the Second World War is what made the difference.” My hope is that we can effect change to address inequality without a Third World War, or yet another destructive financial crisis to justify it.

We should also do what I recommended in the first post - reform monetary policy.

Read that here:

The Single Most Important Thing We Can do to Address Canada’s Economic Challenges

While some economic indicators in Canada are ripping higher, the struggles Canadians are facing are undeniable, and the current policies of the Bank of Canada massively adding stress to Canadian businesses and families alike, in the name of fighting inflation.

-30-

If you’re enjoying these e-mails - share!

Superb post