Understanding Growing Inequality Pt 3: How Debt Drives Inequality - and the reason Politicians Had Nothing to do With It

In the 1970s, English-speaking economies got a new Operating System.

Above: the change in wealth between 1999 and 2012 in Canada. The bottom 20% owe more than they have, with their debt getting worse by $6.7-billion. The top 20% saw their wealth grow by $2.9-trillion.

This is part 3 in a Series on why “the rich get richer while the poor get the picture”.

To recap - Every New Year’s Day, the left-ish Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives announces in the incomes of the top CEOs in Canada compared to the average worker.

“the think tank’s data series that began in 2008, with an average pay of $14.9 million. That’s 246 times the average worker’s pay in Canada, up from 241 times in 2021, when the average was $14.3 million.”

That multiple has more than doubled in the last 25+ years.

In 1998, the Top CEOs were paid 105 times the average wage, while in 2012, the richest CEO’s earned 189 times the salary of the average worker. This year it’s 246 times the average workers’ pay.

Part 1 was about poverty, and the fact social assistance rates in Canada, which are set by provincial governments, have been more or less frozen in Canada for the last 35 years. Part 2 talked about the specifics of how the highest paid executive of a Canadian company earned his $150-million.

While government gets all the blame, the change in the increased concentration of wealth and incomes occurs most in the private sector - not the public sector. That is why Part 3 is about how the role of central banks and monetary policy changed in the 1970s - and the role it has played in creating an economy that makes the rich richer and the poor poorer for over 40 years.

The turning point: the 1970s

For 30 years after the end of the Second World War ended in 1945, when the economy grew in the UK, US and Canada, it grew for everyone: the rich got richer and the poor also got richer.

When people talk about the turning point in when the rich started to get richer in the UK, US and Canada, people will tend to point to the election of Margaret Thatcher as Conservative UK Prime Minister in 1979, Ronald Reagan as Republican US President in 1980, and Brian Mulroney as Progressive Conservative Canadian Prime Minister in 1984, along with the new policies of tax cuts, privatization, union busting and austerity they all ushered in.

While there is no question that Thatcher, Reagan and Mulroney’s governments made inequality worse, it was not their policies that started it, because as Max Rosen’s chart above shows the tipping point in the US, Canada and the UK was between 1976 and 1978, before any of them were elected.

Before conservative partisans get too excited, the reason for this was not because of the “leftist” fiscal policies of Labour in the UK, Democrats in the US or Liberals in Canada: it’s because these governments all adopted similar policies to fight inflation - conservative policies and economic formulas.

Busting some myths about the 1970s inflation crisis

In the 1960s, economic projections were highly accurate, and one of the reasons for that was a formula known as the “Phillips curve,” developed by Bill Phillips, that noted that inflation and employment were linked, with the post-war boom of the 1950s and 1960s. Those predictions started to fail in the 1970s with the advent of “stagflation” - where wages stalled but inflation kept rising. The Phillips Curve did not predict this - but a formula by Milton Friedman did.

Friedman had a different theory of how the economy worked, and argued that inflation was everywhere a “monetary phenomenon”. Inflation in the economy was due to the money supply growing too fast.

To him, the economy was like a balloon and if the government spent more, or borrowed to spend more, it was like inflating the balloon. This simple explanation is easy to understand and seems to make sense, which is unfortunate because it is not correct, for a couple of reasons.

Friedman didn’t include private debt

The first reason is that when it comes to the amount of money in the economy is not up to the government alone. Yes, governments have the power to create new money out of thin air. If you have a growing population, you need to increase your money supply.

Private bank money printing, not government money-printing was also the cause of the German Hyperinflation of 1923, as I wrote in an earlier post.

As this NPR story notes

Before the Civil War, there were 8,000 different kinds of money in the United States.

Banks printed their own paper money. And, unlike today, a $1 bill wasn't always worth $1. Sometimes people took the bills at face value. Sometimes they accepted them at a discount (a $1 bill might only be worth 90 cents, say.) Sometimes people rejected certain bills altogether.

In 1969, Alan Holmes, the Senior Vice President of the New York Federal Reserve, said that banks will extend credit, then get the reserves later, and Adair Turner, who was the Chairman of the UK Financial Services Authority during the global financial crisis has supported this view. Both the Bundesbank and the Bank of England have released papers on the practice.

One of the reasons debt is not included in current mainstream macroeconomic calculations is banking is treated as a 1:1 relationship between the person who deposits a dollar in the bank and the person who is loaned a dollar. By this reasoning, the bank is just a middleman to a transaction that cancels itself out, so it does not need to be counted.

Banks aren’t middlemen - not anymore, anyway. They make money selling mortgages. They get a borrower to take a mortgage, then sell it to an investment bank, that puts it together with a whole bunch of mortgages so everyone is paying into one big fund - a mortgage-backed security. So if you have a mortgage, your house is not the investment: you are.

All financial crises start in the financial sector. But by leaving that part of the economy out of the equations and assumptions, it means that the only entity that can ever be held responsible for inflation is government. In an economy where all the prices that are going up are for private goods, that doesn’t make any sense. But it is politically convenient.

Inflation is driven by crisis and debt, not the total amount of money

The other mistake Friedman makes is that just as interest rates on debt are a price on risk, prices rise in a crisis. Supply disruptions, hoarding, price gouging and uncertainty, war, drought, crop failures, floods - exhaustion of natural resources - all of these can cause price fluctuations.

This is not a new observation. In Sun Tzu’s 2500-year old Art of War, he writes

“Where the army is, prices are high: when prices rise, the wealth of the people is exhausted. When wealth is exhausted the peasantry will be afflicted with urgent exactions.”

In the 1970s, there were a series of crises that had a direct impact on developed economies.

The Vietnam war was still raging.

Facing growing trade imbalances, the U.S. decided to put an end to the gold standard, which hugely disrupted currencies around the world. Smaller countries were battered by speculators and changes in exchange rates played havoc with debt payments in foreign currencies.

In 1973, due to conflicts in the Middle East and a trade war, the Oil Producing and Exporting Countries (OPEC) used their power as a cartel to turn off the taps to the West. The price of oil, which had been stable at $2 a barrel for over a decade, tripled overnight, and by the Iranian revolution of 1979, it had quadrupled again. Within six years, the price of oil had increased 1200%. The 1979-80 global recession occurred when the price of oil soared related to the Iranian revolution.

Since the U.S. and other highly-industrialized countries like the UK were dependent on imported oil for energy, it meant huge disruptions to economies as well as to currencies. Some countries saw massive outflows of money, others saw massive inflows for the purchase of oil. Holland started exporting oil - and that quickly drove up the price of its currency, which suddenly made Dutch exports in established industries like manufacturing more expensive and less competitive.

The U.S. Federal reserve knew that the price of foreign oil was the problem, but it was beyond their control, so they used the tools at their disposal to wrestle inflation to the ground (Bryan 2013). Paul Volcker at the U.S. Federal Reserve hiked interest rates, sometimes as high as 21.5%.

The UK and Canada (among other countries) also had to hike interest rates as well to prevent their currencies from being crushed.

In the midst of this recession, governments - including Pierre Trudeau in Canada and Thatcher and Reagan in the UK and US - were borrowing billions to run deficits at 20% interest to shore up the costs of all the people and businesses being driven into bankruptcy. It also created a base of public debt for each of those countries at colossal interest rates. Manufacturing was decimated, especially in the UK, but around the developed world as well.

Hindsight being 20/20, Volcker is seen by some as the greatest Federal Reserve Chair in history for ‘defeating’ inflation.

While Volcker may get the credit for fighting inflation, prices also dropped because oil prices kept dropping – the very thing that was out of the Fed’s control – reducing the cost of everything. It’s also important to note that on the fiscal side, after initially cutting taxes, Reagan introduced the largest tax increases (yes, increases) in U.S. history and increased spending, while Volcker relaxed monetary policy (dropping interest rates). The size of U.S. government grew much more under Reagan’s first term than it did under Obama’s, which helped drive a recovery that led to Reagan’s re-election in 1984. Reagan’s Keynesian big-spending is ignored by both his supporters and his detractors, since it is at odds with his mythic reputation as a hero to conservatives and villain to liberals.

“The crusade against inflation demands the sacrifice of output and employment.”

The big change in Central Bank monetary policy was to really focus exclusively on fighting inflation.

It is taken for granted that inflation is bad for the economy, but that was not always not thought to be the case: as Arthur Okun wrote in 1976, “The crusade against inflation demands the sacrifice of output and employment,” and we’ll see why.

First, we should understand that there is an important relationship between debt, inflation and deflation.

Imagine for a moment that prices are going up, and people’s wages are going up as well, so that in a single year, prices go up 100%, and so does everyone’s income.

On paper, it looks like nothing has changed: even though your salary has doubled, your purchasing power will be exactly the same - with an important exception - your debt, which will now be smaller in comparison to your income.

The reverse is also true, for deflating prices. If prices suddenly drop by half, and you get a pay cut of 50%, again, it might seem like a wash, but not if you’ve got a mortgage to pay. “The more you pay, the more you’ll owe.” as Irving Fisher said.

For this reason, while inflation is painful for most, it despised by banks, the financial sector and investors, who can end up losing money on their loans.

As Ha-Joon Chang writes:

"Inflation is thought of as a cruel, and maybe the cruellest tax because it hits in a many-sectored way, in an unplanned way, and it hits the people on a fixed income the hardest.” But that is only half the story. Lower inflation may mean that what the workers have already earned is better protected, but the policies that are needed to generate this outcome may reduce what they can earn in the future. Why is this?

The tight monetary and fiscal policies that are needed to lower inflation, especially to a very low level, are likely also to reduce the level of economic activity, which, in turn, will lower demand for labour and thus increase unemployment and reduce wages.

So a tough control on inflation is a two-edged sword for workers — it protects their existing incomes better, but it reduces their future incomes. It is only the pensioners and others (including, significantly, the financial industry) whose income derive from financial assets with fixed returns for whom lower inflation is a pure blessing. Since they are outside the labour market, tough macroeconomic policies that lower inflation cannot adversely affect their future employment opportunities and wages while the incomes they have are better protected."

This is important - “a tough control on inflation is a two-edged sword for workers — it protects their existing incomes better, but it reduces their future incomes.”

Here is why.

The way elected governments try to manage the economy through spending is “fiscal” and the way central banks try to do it is “monetary” and they are completely different in vitally important ways.

A fiscal “stimulus” usually means a government borrows to spend money in areas that are supposed to spur the economy. Infrastructure projects - roads, bridges, etc. are all examples. They are spending more money into the economy than they are taking in. By contrast, a government that seeks to balance its budget through “fiscal austerity” reduces its spending into economy and may also raise taxes.

Part of what defines government spending is that it is not debt. Federal governments transfer money to other governments and to individuals. It is not a loan, it does not have to be repaid, it does not have interest attached. In Canada, over half the federal government’s budget is transfers that go to provincial and territorial governments and to individuals.

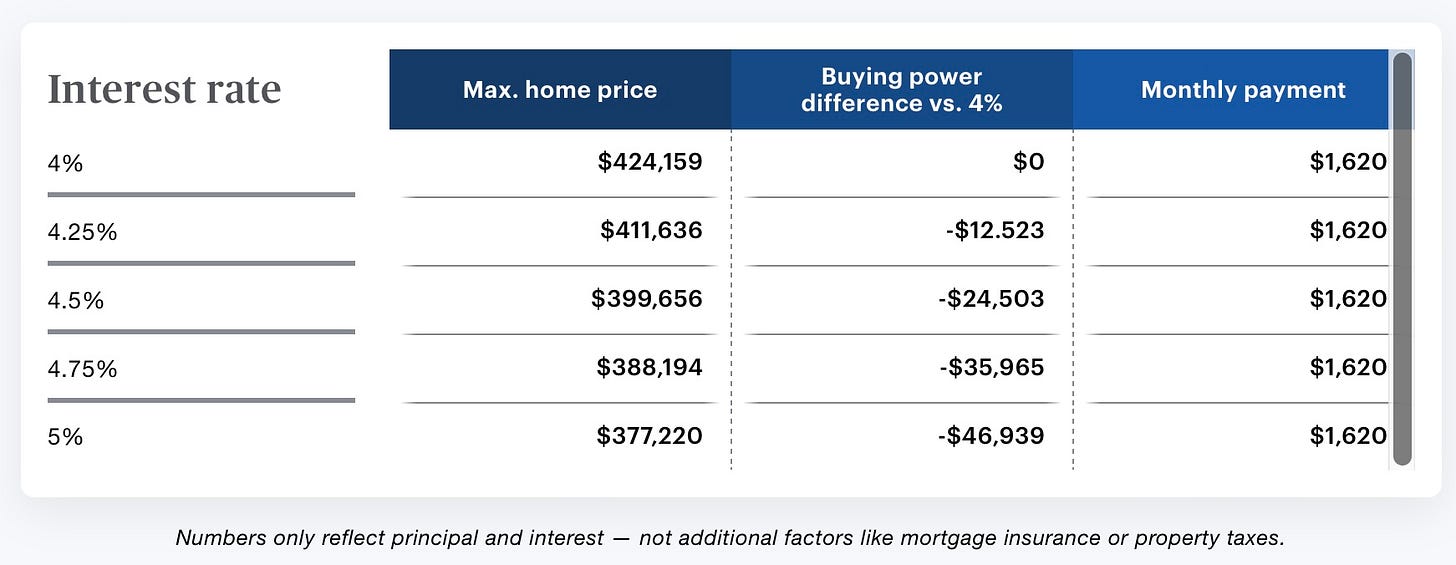

With central banks monetary policy uses terms like “easing” for “stimulus” they mean lowering interest rates, and “tightening” to “cool” the economy is raising interest rates. This is sometimes seen as raising or lowering the “price” of money - the thinking is that instead of taking out a $300,000 loan at 5%, you can get that $300,000 loan at 3%. This is not what happens, especially for mortgages.

Instead, the size of your loan is calculated based on your monthly payments. The same monthly payment at low interest rates can finance a much larger loan than that payment at higher interest rates. Low interest rates create higher loans and more debt, and it is extended to more people.

So, as interest rates drop, the amount of credit banks are willing to extend gets larger, and it especially drives up the price of housing and real estate.

If a borrower can make a $2,000 monthly payment, a 30-year mortgage at 8 percent will finance about a $275,000 home. With mortgage rates of 4 percent, the same payment buys a $550,000 home. Lower interest rates also mean that people who didn’t qualify for loans before, will.

Again, these are not transfers - these are loans, that have to be paid back with ever-growing interest. This “stimulus” is an expansion of debt in the economy, in the form of private credit. Lower interest rates inflate the price of assets across the economy. Individuals pay more for housing and real estate.

The other aspect which should be obvious but is not included is the fact that people who already have assets and high incomes (individuals and corporations) will also qualify for lower interest rates. A corporation that had $2,000,0000 for monthly payments at 8% can get a $275,000,000 loan, at 4% they can get $550,000,000.

Generally speaking, these loans are not being used for “Greenfield” investment to help businesses or factories grow, because new business investments are considered too high-risk. Instead, the debt is used to drive up the price of existing assets that people have already developed and paid for - speculation, and the creation of what analysts have called the “everything bubble.”

The reason for this is the perception that these loans are lower risk, because they are secured, and guaranteed against those assets - but it is an investment that has increased the price without increasing the productive capacity to pay the debt back.

As interest rates drop and more credit is extended, investors can make more money from buying and flipping, instead of buying and holding. Instead of building new factories and creating new jobs, the low cost debt provides funding for more mergers, acquisitions and takeovers, as well as financing stock buybacks. These all lead to greater concentrations of ownership, less competition, and greater income and wealth and the top.

While central bank “easing” through lower interest rates is described as “stimulus”, central bank “tightening” of monetary policy is never described as “austerity” - but that is the effect.

When you reverse the process, and start raising interest rates, it can be thought of as a a form of private austerity. People and businesses with low incomes and few or no assets who did qualify for loans at lower rates of interest will no longer qualify. The loans everyone else will qualify for will be smaller, but the payments will be the same, and in some cases higher. The people least affected at the individuals and corporations at the top, who can still access the lowest possible interest rates.

Monetary “tightening” means banks lend out less, while taking in more money in payments.

As Joseph Stiglitz wrote in The Price of Inequality, in 1993 the Federal Reserve intervened in the economy to prevent unemployment from getting too low, because it risked getting to a point that wages might rise, driving up inflation. The real consequence of this is that when central banks engage in their version of austerity, it means pushing homeowners and businesses into bankruptcy, and increasing unemployment.

This also increases the concentration of wealth, because people who had assets (businesses, homes) are losing them, and they are then snapped up by investors at fire sale prices.

The Impact of Monetary “Stimulus” and Private Debt

When you consider the impact of a Monetary Stimulus, there a couple of critical things to observe.

First, that when interest rates drop, it means that a single middle-class borrower can get access to tens of thousands, or hundreds of thousands of dollars in loans to spend that they would not otherwise have had. When multiplied across the economy, it adds up to hundreds of billions of dollars - much more than government spending.

This revenue - which goes mostly into the housing market, translates into more revenue and taxes for governments, but it is through short-term real estate bubbles, which when they crash define the business cycle.

After interest rates were over 20% in the early 80s, they dropped, which led to the 1980s stock market and housing boom in the U.S. Canada, as well as a crash.

The same thing happened in the 1990s. As interest rates dropped in Canada and the U.S., it fuelled a second boom, including a boom in tech stocks, which resulted in the dot.com crash of 1999.

That led to a further lowering of interest rates, which drove a further housing boom, which resulted in a crash and the global financial crisis of 2008-09.

The assumption is that after recessions, people and incomes just bounce back to where they were. The reality is that austerity programs - fiscal ones by government and monetary ones by central banks - are more like a boa constrictor tightening its coils around its prey. Every time the captured mouse breathes out, the constrictor squeezes tighter.

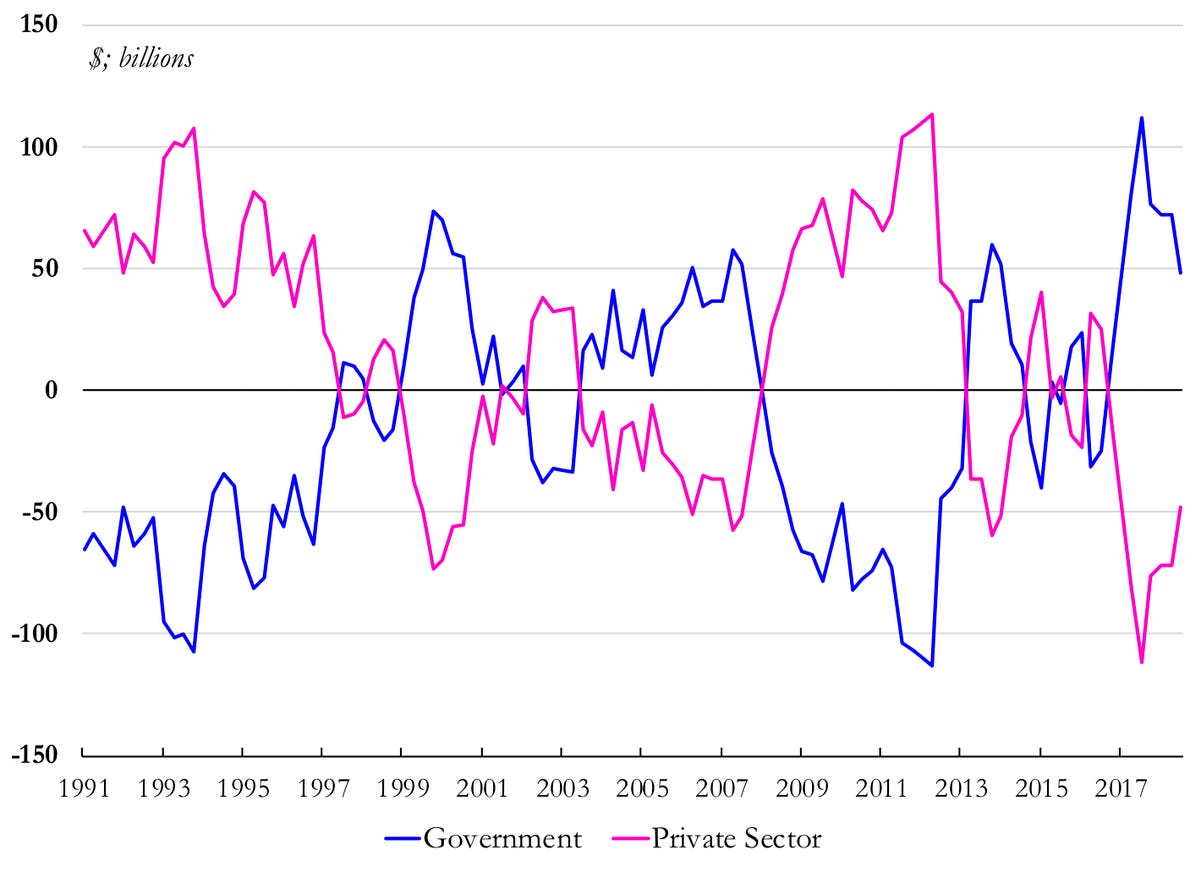

As mentioned, when central banks drop interest rates and people take on more private debt, government revenues go up and it helps balance the budget. That creates the impression of stability, but the reality is that there is 1:1 inverse relationship between private and public debt. When private debt goes up, public debt goes down. When public debt goes up, private debt goes down.

The correlation could not be more clear - this is a Government of Canada Chart, and public debt to private debt is a mirror image.

Annual Change in Financial Assets, 1991-2018

Source: Cansim table 36100580. ‘Private sector’ aggregates data for ‘Households and non-profit institutions serving households’, ‘Corporations’ and ‘Non-residents.’ ‘Governments’ is ‘General governments.’ Note: Series is the year-over-year change in quarterly values.

When the economy is suddenly flooded with new private debt, it creates a temporary boom. This is the reason that in the 1990s, so many governments started running surpluses. The Liberal Government in Canada did, the Clinton Democrats in the U.S. did, and Tony Blair in the UK did.

When the crash comes, it means that revenues drop and government stabilizers kick in. All financial crises start in the financial sector, because private lenders extend more credit than can be paid back, because so much of the economy is debt based, and while the economy is affected by shortages, crises, storms, disease, etc., debt keeps growing.

Inflating the cost of assets through debt means inflating the cost of overhead, for two reasons. When it comes to workers, they need higher and higher salaries to be able to pay their mortgages or rent. When it comes to business (including landlords), they need to increase prices in order to pay the debt on the assets they bought.

Many economists have been warning and calling for change, because the current policies are only making the situation worse. As William White said, today’s solutions are only making tomorrow’s problems worse.

It has to be emphasized - it is not just workers who have been hurt by this growing concentration of wealth - it’s businesses in the “real economy” who struggle to compete. Good jobs in productive industry have been crowded out by the debt while trillions in investment goes to inflating the price of real estate.

We’ll get to detailed solutions more in later chapters - but to reduce inequality and bring back healthy growth, we have to prune the overgrowth of debt. Central Banks can and should play a role, and as Adair Turner and William White have written, governments need a formal plan to help reduce private debt burdens, while providing access to non-debt capital for “real economy” business development that addresses some of the conflict costs.

In other words, we need a Marshal Plan to turn the economy around. Local supply chains, more competition, and Canadian ownership must all be a consideration.

-30-