This One Chart DESTROYS Conservative Theories About Inflation

Yes, this is a shameful clickbait headline. It's also true.

I was writing about oil, the carbon tax and inflation when I came across this handy chart, on the Government of Canada’s page about 30 years of crude oil prices.

What it illustrates, in very clear terms, is that inflation of oil prices - which drive consumer inflation - are due to conflicts and political events.

These price changes were not caused by “too much money chasing too few goods”. There are real-life supply shortages, from natural disasters, financial disasters, and some are “engineered” and deliberate strategies: wars, financial crises, strikes, natural disasters, and collusion by cartels.

In fact, both oil and finance can and are used as weapons to disrupt economies, as we are seeing right now around the world. Small regional conflicts - including the war in Ukraine and conflict in the Middle East - affects global oil supplies and prices.

Surges in inflation being a conflict phenomenon are being supported by theory. In April 2023, Guido Lorenzoni and Iva ́n Werning wrote a paper, “Inflation is Conflict”Eckhart Hein wrote a Post-Keynesian perspective “Inflation is always and everywhere ... a conflict phenomenon: post-Keynesian inflation theory and energy price driven conflict inflation.” There’s even a notable paper from 1977 by Robert Rowthorn.

The chart above lists military conflicts as well as financial disasters that had an impact oil price inflation.

Conflict means uncertainty, and uncertainty raises costs, as well as opportunities for exploitative profit-taking.

This is not a new observation: it is written in Sun-Tzu’s The Art of War:

“Where the army is, prices are high; when prices rise, the wealth of the people is exhausted. When wealth is exhausted the peasantry will be afflicted with urgent exactions.”

Chia Lin: … Where troops are gathered the price of every commodity goes up because everyone covets the extraordinary profits to be made.

This contrasts with the idea we’ve been living with since about inflation since the 1970s, based on the ideas of economist Milton Friedman. Friedman argued that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” There is another term that inflation is “too much money chasing too few goods.”

The idea - which is very common - blames price increases and inflation on customers bidding up prices - on customers’ demand and customers having “too much money” and not on the people who run businesses increasing prices. This reversal is a neat trick, because it blames government and customers for inflation, not the people setting the prices.

Friedman’s theory seems to make intuitive sense. Because is treats the economy as if it’s just a big pool. If you have an economy, and you “add more money to it” then it’s as if you are “watering down” the supply of money that’s already there.

Another metaphor is that the economy is like it’s a giant balloon, or a pressure container, and money as if it’s air. By this theory, new government spending will increase prices, especially if they are borrowing and running a deficit. It’s perceived as “adding” money.

This isn’t accurate, for a number of reasons.

First, the economy is not one big pool. It is millions of different accounts - public, private, local, national, international.

Second, one of the reasons governments run deficits is in response to a collapse in the private sector. People have lost money, lost jobs, and businesses are going under - the private sector is faltering.

This means that government revenues will also drop, first because people and businesses are paying less in taxes.

In such an instance, if all the government does is maintain its budget, it will have to run a deficit just to maintain the status quo for services. This is putting money into an economy that is shrinking. Government is not growing: the private sector is shrinking, and government deficit spending can prevent it from shrinking even more.

Ideologues who equate the judgment of the market with the judgment of heaven may believe that it is wrong to interfere with the verdict - any intervention is treated as wrong. This belief was expressed by US Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon - who had phenomenal personal wealth and used the position, not just to further enrich himself, but arguably to create the conditions for the crash of 1929, and for making the Depression worse:

“The ‘leave-it-alone liquidationists’ headed by Secretary of the Treasury Mellon felt that government must keep its hands off and let the slump liquidate itself. Mr. Mellon had only one formula: ‘Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate’.He held that even panic was not altogether a bad thing. He said: ‘It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people’

To use an obvious real-world example, imagine a worker making $24,000 a year loses their job. They can’t work due to a temporary issue - let’s say a train derailment that disrupted their workplace.

If they lose income, and the government tops them up - how can it be said to be inflationary? If they had $2,000 a month, then nothing, then were back up to $2,000 a month, there is no net increase in the money supply.

So if the government is running a deficit, it depends where the money is going: if it is going into the creation of new value and investments that will deliver greater material efficiency, it will not be inflationary.

If the money is being used to drive up the prices of existing assets, it will be inflationary. If the money is being used to ensure that people can pay their bills (buy food and medicine, at current prices, for example) it is not inflationary. If it is used for new investment - new businesses, successful innovation, capital investments that improve productivity - it will not be inflationary.

Central Bank “Stimulus” means Private Sector Money Creation

When central banks drop interest rates, banks extend more private credit. It injects huge amounts of money into the economy - largely through mortgages.

It is not government money: it is private money, and because it is based on debt, it means that the terms and interest rates will be orders of magnitude better for “prime” borrowers than for most citizens.

It is not governments’ fiscal spending that injects huge quantities of new money into the economy over the last decades, it is that when central banks lower interest rates, banks extend more private credit.

For most individuals, the changes in the debt that they will take on in a mortgage to buy a house are far greater than any government fiscal intervention. The lower the interest rate, the larger the loan - and the higher the price of the asset being purchased.

This is what has been driving up the prices of assets - specifically, housing - for decades. As economists William White and Edward Chancellor have argued, we have a 20+ year “everything” asset bubble as a result, which the pandemic accelerated and made worse.

That is why we have housing crises, not just in Canada, but in the U.S. and the UK, as well as soaring stock markets amidst political rage. We keep adding more fuel to the fire of debt.

We are living through the terrible consequences of being wrong on inflation

Friedman’s idea, which is widespread, is that government spending and deficits cause inflation, because of the belief that it gives people too much money to spend, and that they are driving up prices.

The orthodox, “fiscally conservative” policy response is to try to lower inflation by depriving people of the money to buy goods.

Elected Governments may simply sit back and do nothing, or they may actively intervene in the economy to make it harder for people to buy. Fiscally, they may cut or freeze income supports for people who are not working, or refuse to extend assistance.

The fiscal taxing and spending of elected governments to “stimulate” or “cool off” the economy is completely separate from the way central banks intervene and change policies to “stimulate” or cool the economy.

For all the blame heaped on governments, the impact of interest rate changes and bank lending has an impact that is much larger and more disruptive effect than the fiscal and tax actions of most governments.

The change of a single point in interest can interest or lower the size of a mid-range North American mortgage by nearly $50,000.

A slight rate increase might seem minor, but this small increase in your monthly payment can add up over time and affect your buying power.

If you look at a borrower with a monthly income of $4,500 and a debt-to-income ratio of 36% who makes a 20% down payment, even a quarter of a percent increase can mean they’ll be able to afford roughly $12,000 less over the course of a fixed, 30-year mortgage. With a 1% increase, the price of a home they can afford drops by more than $45,000.

The table below shows the difference in buying power for mortgages with rates between 4% and 5%. Even when the monthly payment is the same, the maximum price of a home the borrower can afford goes down significantly when the interest rate increases slightly.

This is the direct link between interest rates and banks’ willingness to extend credit and inject new private money into the economy.

A change in the interest rate of 1%, makes a difference of $46,939 per mortgage. That is a difference in of $50,000 more - plus interest - that the borrower will have to cover. It drives up the price of real estate by $50,000, and it has injected $50,000 in new, privately created money into the economy.

That change by a central bank makes the difference of $50,000 in new debt for a single household. Multiply that across the economy and it adds up to hundreds of billions or trillions of dollars in debt that is driving up the price of existing housing stock.

This is a deliberate economic choice - to have consumers drive the economy with their personal debt.

The consequence is that Canadians are extremely heavily indebted. The wealth that people have in their homes is because other Canadians have taken out debt.

Canadian household debt reached a staggering US $2,116.3 billion in April 2022.

In 1980, the household debt to income ratio was 66%. Even before the pandemic, in the last quarter of 2019, Canada’s debt to income ratio was three times as high: – around 180%.

In 2023, US Household Debt Reached $17.5 Trillion in Fourth Quarter.

At the beginning of the pandemic, central banks like the Bank of Canada, the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England all dropped their interest rates close to zero, with the claim that it would help people “invest” during the crisis.

The result of dropping rates was a colossal expansion of debt, which was used to push up asset prices. Individual homeowners aren’t the only people who borrow: so do institutional investors and funds, who also use debt to buy assets and consolidate.

Central banks, and economists across the developed world are ignoring these realities because they are still operating on an outdated understanding of inflation.

The higher interest rates are driving people and businesses into bankruptcy, because policymakers have the causes, and therefore the cure, for inflation, wrong.

Edward Chancellor, an economic historian and financial advisor, has argued that “It Will Turn Out to be Largely Impossible to Normalize Interest Rates Without Collapsing the Economy” for these reasons.

In a 2022 interview, he said:

As the cost of capital rises, there is going to be a reallocation of capital.

Which means a wave of bankruptcies?

It’s essential that capital is reallocated from low-return to higher return businesses. That is the cleansing function of an economic downturn, what economists call the pit stop theory of recession. The economy takes a pit stop, then gets back on the road, faster than before. We avoided the pit stop recession in 2008/09: It was the biggest economic downturn since the 1930s, but actual insolvencies were much lower than in previous recessions. A lot of cleansing, a lot of the reallocation of capital, has yet to take place.

Here, Chancellor is making another error - the very one that Andrew Mellon, the liquidationist U.S. Secretary of the Treasury made, and that many economists make. They treat capital as something indestructible, like water, that flows from place to place.

When people go bankrupt, and when companies and entire industries fail, the capital is lost and can’t be recovered. The money is not there anymore.

This is the problem with many Western Economies - especially Canada, the U.S. and the UK.

The “capital” is all personal debt locked up in overpriced housing, especially in Canada, and despite the desperate needs of buyers, there are vast numbers of people who do not want housing prices to go down, because it represents an irreplaceable loss.

If you are a new home buyer and prices go down, you could be underwater on your mortgage - when your mortgage is worth more than the house. That means that even if you sell, you will still own money.

For many people, especially Canadians, their house is their retirement plan: If you are retired and you are “house rich” and “cash poor” dropping housing prices means less money in retirement.

Municipal governments rely largely on property taxes for revenue. That means more housing and higher housing price are considered “economic development,” not overhead.

The mortgages themselves are sold as investments for pension plans.

Homebuilders, developers, real estate, finance and insurance can all make more money without their costs going up, which means higher profits and returns.

Repeatedly, in the last decades, when faced with a crash in the price of assets, governments and central banks in particular have intervened on behalf of the investor, in order to keep asset prices from dropping. In 2008, when there was a global financial crisis, central banks did “quantitative easing” - when investors and even companies had bad accounts and assets that were being defaulted on, they could sell them to central banks in exchange for “liquidity” - which is to say, cash.

That is one of the reasons why we have housing crises and housing markets that are overvalued by hundreds of billions of dollars, and why our developed economies are slowing down. Part of it is an ideology, of investor protection - which is that the investors keep the gains while shifting the losses elsewhere.

However, the existence of all that private debt serves as a ceiling to Canada’s housing market that keeps it from dropping. It is also debt with interest, which means that it is growing all the time, even when the rest of the economy isn’t.

The challenge of unwinding this is significant, but it is not impossible. Simplistic solutions, like interest rate manipulation or tax cuts are not going to change the situation, because the problem is the market, not just government.

Canada has a problem with its economy, and the idea that everything is the government’s fault is wrong - when the problems are being caused by distortions and bubbles in one part of the private market - finance and real estate.

A Marshal Plan for Revival

At the end of the Second World War - The Marshal Plan was launched to help support the recovery of European and other countries. It did two things: monetary and debt reforms, paired with new industrial investment.

Step 1: Deflating the debt bubble

To resolve the housing and economic crisis in Canada, so that prices can actually normalize requires reducing mortgage debt and farm debt. There are ways to do this, as spelled out in this paper by a Bank of Canada researcher, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Debt Relief Policies During Recessions.”

“Since the Great Recession, a widely held view is that alleviating underwater borrowers’ financial distress could have prevented the sharp rise in foreclosure and dampened the fall in house prices. Moreover, preventing large initial declines in house prices might have reduced subsequent foreclosures, thereby supporting house prices at later dates and household spending over time. … I find that in a recession that involves an unusually large drop in house prices, a large-scale mortgage principal reduction can lower foreclosure but does not mitigate the recession. Instead, it amplifies a recovery.” (Emphasis mine)

This process amplifies the recovery because funds that are currently going keeping the price of housing high, or rising, can be spent and invested elsewhere by individuals. As a policy, it can also be targeted for maximum effectiveness.

The reason for the focus on household, personal debt is that it is debt that was invested in a non-productive asset - an individual’s home.

Private Sector Recapitalization and Investment

If individuals and households are able to redirect their spending, it can help drive a private sector recovery.

Because of the size of the Canadian housing bubble, there needs to be a strategy to replace lost value of debt investments with new investments in more productive enterprises, and increase access to capital, in the form of equity, not just debt, for Canadian owned- and operate enterprises to start up, scale up and upgrade.

The Bank of Canada played a role in financing such enterprises in the post-war era through the predecessor to the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC). The BDC’s mandate and practices need to be overhauled, since it now operates little differently than other banks and charges interest rates for loans that verge on usury.

This should be part of a new national industrial policy, to make investments in productive businesses and organizations - and if they are to have the maximum community return on investment, local ownership makes a difference.

Public Sector Investments for Renewal & Economic Security

There is an urgent need for infrastructure renewal that should not be delayed. Infrastructure investments are an additional factor of production, and the focus should be on public financing, because it is the lowest cost option. Private financing for such projects means higher costs on infrastructure projects that reduce costs for business and citizens alike.

It should cover:

Energy security - this includes improved infrastructure, as well as the development of alternative energy sources as a hedge against oil price volatility

Food Security - Canada grows more than it consumes,

Health Security - We need to ensure that we have secure access to pharmaceutical and medical technology

Research and Development in Agriculture, Health, Energy and Climate Change

For decades, the pursuit of economic efficiency has been often been through financial engineering. Both resilience and flexibility depend on redundancy.

That is why an aggressive push on investments in fighting climate change - planting forests and measures aimed at rewilding, electrification and energy efficiency will all make a difference.

These are all entirely possible, and will help restore a market and an economy that is in better balance with itself. It is possible to lower the cost of housing.

The question is not whether we can pay for it: it’s whether we can do it. In 1942, Keynes gave a radio address in which he said “Anything we can do, we can afford.”

Keynes was right. Friedman is wrong. The sooner we leave conservative myths about inflation behind, the sooner we can get on with the work.

DFL

PS: if you haven’t read it, here’s my companion piece:

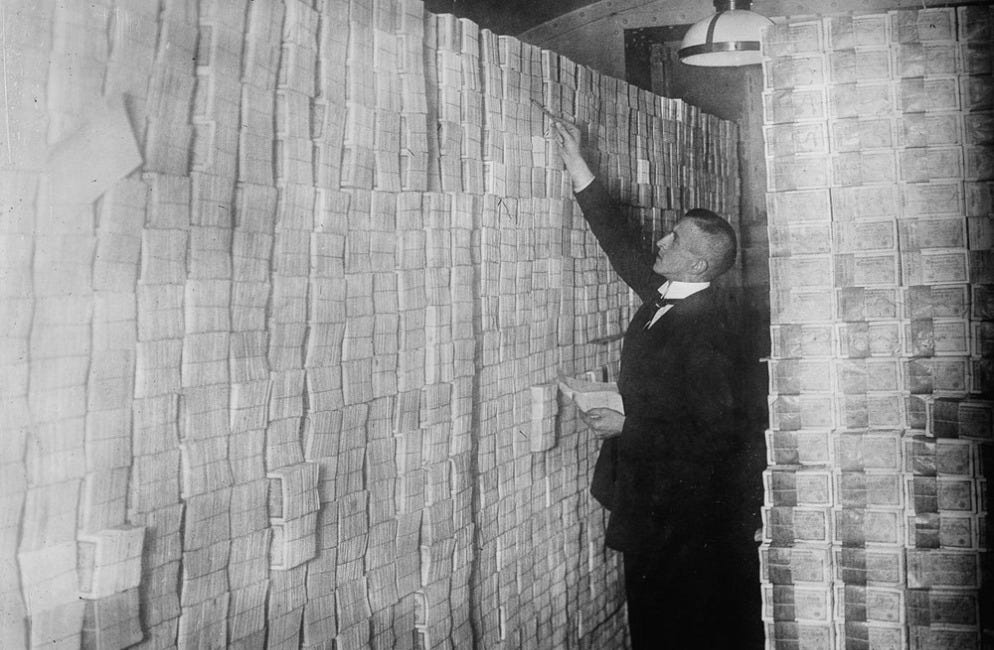

The History of Hyperinflation in Germany after WWI is Dangerously Wrong. Here's Why That Matters.

Many economists, historians and news articles will seek to explain the dangers of hyperinflation by citing Germany, but the history is almost entirely wrong. In the mid-1920s, there was a period of hyperinflation in Germany when the value of money dropped so badly that people were wheeling money around in wheelbarrows or used it as wallpaper (all true).

-30-

You write, "... are due to conflicts and political events..." but there is also a monopolist (OPEC+) setting price. Back pre-1970's when the Texas Railroad commission were setting the oil price there was almost negligible nominal inflation, and no nominal inflation pressure from oil. (You can fact check me, I'm just shooting out a comment from dim memory.)