We've Lost Good Jobs and Local Businesses because of 45 of Years of Supposedly "Business-Friendly" Policies

Part 2 of the Bull Elephant in the room: It's not just workers who have seen their incomes stagnate for years - so have Canadian businesses.

In the first part of my discussion about the low quality of debate about finance and the economy in Canada, I pointed out that the economists slamming government policy, taxes, and interference in the private sector all worked for banks that received billions of dollars in bailouts to keep them from going bankrupt.

(Here’s the article)

My point was that there was a general lack of self-awareness, as well as short memories when it comes to the recent history of their own employers, in an industry in which they are experts.

I didn’t have room to bring up another economist, who was highlighting the problem that I think is the single greatest danger to the Canadian economy - private debt.

Private debt is what brings down economies and causes financial crises, where banks collapse and people lose all their money. Crises like these have happened for centuries.

Canada’s indebtedness brought out another moralizing scold in the Globe, a professor of finance , George Athanassakos, who wrote that Canadians need to learn how to live within their means.

It’s an op-ed in the truest sense of the word, in that it is an opinion, but it’s not supported by evidence.

Professor Athanassakos is expressing an ideology - an attitude and a common one - that if people are in debt, they are to be blamed for it, when realistically speaking, debt is the only possible way to pay for education, housing, medication or groceries.

Surveys have shown that many Canadians are $200 a month away from insolvency.

It’s just moralizing and trafficking in tired old stereotypes about why people are poor - they can’t control their impulses, and end up buying useless trinkets or wasteful luxury, when for many people in Canada, because wages have stagnated and the prices of essentials have risen.

This is a professor of finance:

He writes:

I believe we live in an era when we demand instant gratification. We want everything now – cannot wait to have it tomorrow. No one these days wants to live within their means.

This has led to a North American economy that is hard to explain by typical economic models. We have an economy that is performing better than expected while at the same time debt levels are going through the roof. People have forgotten how to live without credit and debt, falling victim to an addiction that helps to sustain what is perceived to be a normal life. That includes racking up debt to help pay for everything from buying meme stocks on margin to overpriced vacations.

This positioning is not just unscientific, it’s not accurate.

It’s based on the idea that people who are rich must be doing something right, and showing discipline, and are “good” with finance and have self control, while people who are poor are doing something wrong that must be corrected, and are poor because of their impulse control.

There’s is no evidence for this: quite the contrary. There’s plenty of evidence that most of the debt is to put a roof over your head, or get an education so you can actually get a job that will pay you enough to live on. Those are the costs that have been dumped on younger generations for three decades.

I know this because I lived through it. In the 1990s, in the middle of a degree, the provincial government eliminated bursaries and tripled the amount of student loans. In a single year, $3,500 in debt + a $3,500 bursary was replaced with up to $14,000 just in debt. The result that students in a four year degree would graduate with $56,000 in debt instead of $14,000. For anyone in the middle of a degree, they could be faced with dropping out or taking on more debt, and tuitions have soared along with debt.

Yes, people at the top of the income scale are able to buy more luxuries, but the people who are in trouble with debt are borrowing because to cover the necessities of life.

The idea that “financial literacy” is the key to prosperity ignores that in an economy where so much is based on debt that it makes it cheap to be rich and expensive to be poor.

We know this because of data collected in Ontario by Hoyes Michalos, an Ontario insolvency trustee does outstanding work gathering and compiling information on distressed borrowers.

They’re not buying meme stocks or overpriced vacations. They are paying the necessities of life - groceries, medications and housing, or school, as their annual “Joe Debtor” reports show.

Due to the rising cost of living, 1 in 4 seniors is hitting retirement with debt, including high-risk debt, to the extent that seniors are turning to payday lenders.

Credit cards and payday lenders are driving insolvencies, and the age group with the highest balances are seniors, with $23,296.

In 2023, 91% of insolvent debtors filed insolvency with an outstanding credit card balance, up from 88% in 2022. Average credit card debt among insolvent debtors with a credit card was $17,816, up 12.8%.

”Vulnerable households often turn to credit cards and lines of credit to keep up with mortgage payments until their credit options are exhausted.”

The narrative is clear, sustained and wrong: that borrowers are in the wrong for taking on bad loans, not that the credit card companies or banks are in the wrong for what is often exploitive and predatory lending - or that the government should be doing a better job of managing the economy.

Here’s the thing - for all that people complain that Canada is supposed to be socialist, or communist, the government does not run the economy.

In fact, the Canadian Government had shrunk so much over the years that it hit its smallest size, as a percentage of GDP, since the 1930s, because of Conservative tax and spending cuts.

How the economy has changed

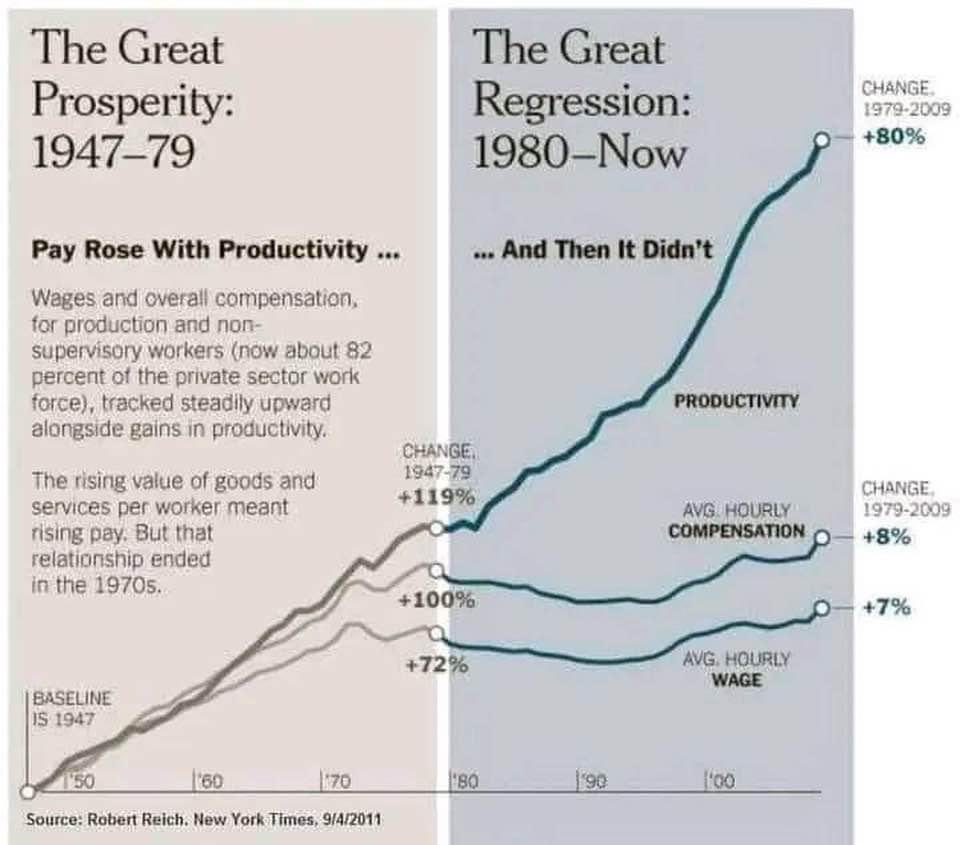

In the last 50 years there have also been massive disruptions to the Canadian economy, because people’s wages have stagnated, and people have lost good jobs as small and medium sized businesses struggled to compete, or were bought up and shut down as part of mergers and acquisitions.

When we talk about income inequality growing, and the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer, it’s not just people and workers.

It’s businesses too - the “real economy” - manufacturing, industry and what people used to call “Main Street”.

The economy really did used to function differently in Canada and in the U.S. It was more equal, and when the economy grew, it tended to grow for everyone. It was possible for middle and working class people to buy a house on one person’s salary.

While income taxes were higher for the people with the highest incomes in the US, UK and Canada in the 1950s, the top marginal rate was around 90%, it’s not just that people have been able to keep more of their income that made them wealthier. People’s incomes tended to rise together, and that stopped in the 1970s.

The so-called “Golden Age of Capitalism” for Canada and the US, from 1945 to 1975, when the economy grew, it grew for everyone.

There have also been new trade agreements, especially with China, that opened the floodgates to a lot of manufactured goods. We are told by economists that imported lower cost goods reduce inflation

“Free-Market Economist Two-Step”.

FME: Trade policy X will make us richer on aggregate

Other: What about winners and losers?

FME: Policy can be created to compensate the loser.

Other: Sounds good, here’s a policy we could use?

FME: Redistribution is distortionary, this cannot be allowed!

A 2013 paper found 44% of job losses in US manufacturing between 1990 and 2007 were due to Chinese competition. $1,000 in Chinese imports per worker, per year, reduced annual income by $500 per worker, but government benefits only rose $58.

Cheap imports don’t close the gap - in part because of what gets cheap. In the U.S., the items that have dropped most in cost are TVs, toys and mobile phones - nice to have, but not always essential.

The costs of things that matter - like health care, education and food - kept going up.

If people want to ask “what happened in the 1978?” the answer is not just inflation, or stagflation, because inflation of the 1970s and early 80s was temporary.

The permanent change was that governments in the UK, Canada and the US all adopted new policies to fight inflation - especially the belief that inflation could be controlled and moderated by the actions of the central bank alone, and that government fiscal stimulus should be avoided.

The ideas were fundamentally conservative and libertarian, but the governments that passed them were not: they were Labour in the UK, Liberal in Canada, and Democrat in the U.S. And they have stayed in place ever since, no matter who was in elected.

1970s currency distortions due to oil prices & lifting the gold standard.

In the 1970s, the price of oil tripled overnight after the OPEC Cartel - the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries - tripled the price of oil.

This had a massive shock on developed nations in multiple ways. The price of oil had been stable at about 2$ a barrel for years. The effect of oil price shocks were already known to have recessionary effects going back years.

Aside from consumer inflation, it also introduced the idea of the “Dutch disease”, in part because the high price of oil altered the economy of oil-exporting countries, because of the impact in their currency exchange rate.

Holland started selling large quantities of oil (as did Canada), which drove up the value of Dutch and Canadian currencies. This lowers the price of imports while driving up the price of domestically made goods, as well as goods for export.

For Canada, in the 1970s, the oil boom had huge impacts on the economy as well, with similar challenges. Canada’s oil patch became immensely profitable.

The other major change was that the U.S. had abandoned the gold standard, which which was lost because speculators added volatility to currency markets. That could wreak havoc with a national economy, because overnight changes in the value of a currency meant that finance officials suddenly had to come up with millions more in money they didn’t have - and cost more to acquire.

This had an impact in Canada after 1998. Canada lived through an oil boom and and oil bust, and oil prices were creeping up in the late 1990s. Prior to 1998, the relationship between the Canadian dollar and price of oil was not so direct, but after, it was.

The price of oil also started to climb from about 1998, spiked up to over $100 a barrel, holding there for several years, between 2008-2014.

This meant that the Canadian dollar was on a par with the U.S. When it goes up quickly, it created challenges for manufacturers - Canada has an enormous amount of cross-border trade with the U.S. - including auto manufacture. Companies with plants on both sides of the border faced all kinds of sudden disruptions, because their contracts with in last year’s dollars.

It also meant that Canadian consumers and businesses could source parts and goods from other countries much cheaper.

Quebec and Ontario between them lost hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs.

There had been predictions Canada would be an “energy superpower” because our oil reserves are some of the largest in the world.

It was widely assumed that oil prices would stay high forever. In the U.S., the fracking revolution increased U.S. oil and natural gas production so much that for the first time in decades, the U.S. produced enough oil for all of its own needs.

The other was a 2014 decision by Saudi Arabia to deliberately drop the price of oil by $50.

This caused agony in Alberta Canada, and Saskatchewan, for the basic reason that the oil boom also created a housing boom. When diesel mechanics are making $300,000 a year, they can afford quite a lot of house. And when every single media outlet, politician, financial expert - basically everyone - is telling them that the price of oil is going to stay up forever, it makes sense to get a $1-million mortgage, because you can afford it, and that is what all the housing costs where you work.

Then, when the price of oil plummets, the party is over. Jobs are lost, and the currency changes. That makes it more profitable for exports, but the businesses aren’t there anymore. They’ve been offshored, because several years with the Canadian dollar at par with the U.S. meant that imports became very cheap.

One more basic point about the oil industry, and how it is different from other industries like manufacturing, which is that by the nature of the work, the oil industry involves a lot of machinery and fewer people for a product that is profitable, in part because it is single use, and therefore is in continuous demand. We buy oil and gas, burn it once, and it’s gone. By the nature of the business, a few people can earn a lot of money. And people are still being replaced by technology in the oil industry, right now.

The manufacturing jobs that were lost were industries in which, getting the work done requires more people who are also well paid. Craftspeople, artisans, engineers, including local executives, middle managers and owners.

This is what the loss of the middle class and good working class jobs is about.

When these jobs are lost, people don’t find one that is as good again.

They have been destroyed by technology, by trade, and in many cases, our refusal to enforce or update intellectual property laws for creators and innovators.

One is for those people who lose their job or their income, the jobs with comparable pay are not there. So the debt that they have already taken on gets harder to pay off. They did nothing wrong. And while no government will compensate them for their loss, due to the government changes in policy, they can get a credit card.

The second is that the default solution to these challenges has been to make the situation worse with more debt, which is overhead for the entire economy.

Because one of the reasons why competing against the workers in lower cost countries is a challenge, is that their wages can be low because the cost of housing is so low.

And that is the other aspect of the economy, which is that the FIRE economy has been growing as the real economy and industrial capitalism have been shrinking.

When we talk about the economy, we oversimplify it

Often, people will just split the economy in two - government and business: the public sector and the private sector. That really is a gross oversimplification, because we actually need banks in here, as well as workers. We could add other sectors, but let’s keep it simple for now.

We do have make a point that, not only are there government whose jurisdictions mean they do very different things, the same is true for business.

There are two very different types of business.

There’s what people call the “real economy” where people are working and exchanging money for a product or service. Agriculture, manufacturing - media, publicly owned corporations, restaurants, construction, transportation, health care, education, accountants, you name it. It’s about the kind of work that is being done - it’s money in exchange for something in the world that’s not money - a good, a service.

That’s “industrial capitalism” and every developed country became “developed” by adding public co-investment in infrastructure and education, because they pool investments to invest in shared projects that reduce costs and efficiency and raise the standard of living for people and businesses alike.

Simon Patten, the first professor of economics at America’s first business school, the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, defined public infrastructure as a “fourth factor of production,” in addition to labor, capital and land. But unlike capital, Patten explained, its aim was not to make a profit. It was to minimize the cost of living and doing business by providing low-price basic services to make the private sector more competitive.

That is something in common for all prosperous countries, and it is also how Canada and the U.S. pulled themselves out of the Depression, rebuilt and created the middle class and the so-called golden age of capitalism.Governments invested in infrastructure and provided more security so more people could take risks to prosper.

Really, we need to split the private sector in two, because there are two very different types of business.

The real economy, and the FIRE Economy - finance, insurance and real estate. One of the things about the FIRE sector is that it is extractive. It takes out more than it puts in to the real economy - it has to, to make a profit.

The other thing about finance, insurance and real estate, is that between them they can set up a self-reinforcing loop that can distort the market, create and drive bubbles, including property and stock market bubbles.

Except that when they burst it’s less like a bubble and more like a nuclear bomb going off and there’s a big hole where the real economy used to be.

This matters for business, because over the last decades, we’ve seen communities lose factories with good jobs, but the pain is everywhere across the country. It is in cities and in small towns.

It’s been called “deindustrialization” or that we’re “post-industrial” or “late capitalist” when what it is, is financial capitalism. It is a direct consequence of intellectual coup against Keynes in the 1970s staged by the Chicago School, who were nothing if not fond of coups.

All of this debt is driving economic anxiety in developed countries and it is driving economic crisis across underdeveloped countries, because they are also drowning in bad debt. The economic crises and refugee crises around the world are being driven by countries’ economies having broken down because of debt.

Throw in disruptions from internet, tech and AI, whose economic advantages are made possible by exemptions for paying for intellectual property rights that they enjoy themselves, as well as rampant tax avoidance.

These are the reasons why Canada’s economy is not as productive as it should be to ensure our present and future prosperity.

To add to all of that - the private debt household on which we have been building our economy is a proverbial house of cards, which also makes our economy highly volatile and less resilient.

If we accept that this is an accurate story of what’s going on - the right diagnosis for what ails the economy - then it starts to point us towards solutions that will work, because more of the same is not, and more of the same is all that is on the table.

Proposals for Solutions - Coming Soon

-30-